Introduction

Several studies have shown that noise pollution can affect the behaviour, reproduction and survival of wild animals living in cities (Slabbekoorn & Peet, 2003; Warren et al., 2006; Bonier et al., 2007; Duarte et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2017). However, most of these studies are experimental and made under controlled conditions, usually with a single species (Berger-Tal et al., 2019). Few studies have addressed the impact of noise pollution at a broader ecological level, the community, by using an ecoacoustics approach. Ecoacoustics investigates all the sound sources (the soundscape) as a means conveying important information about the ecological status of ecosystems (Sueur & Farina, 2015).

According to Schafer (1977), sounds are ecological properties of landscapes, and soundscapes are the acoustic characteristics of an area that reflect natural and anthropogenic processes. A soundscape is formed by three acoustic components: biophony (biological sounds such as animal vocalizations), geophony (natural non-biological sounds, such as that produced by wind, rain, and thunder) and anthropophony (sounds generated by humans such as traffic noise; Pijanowski et al., 2011). The study of soundscapes can provide valuable information on animal communication dynamics, help the assessment of the environmental status of habitats and their spatiotemporal variations, and investigate the noise effects on different ecosystems (Pieretti et al., 2011).

All habitats have some level of anthropogenic noise, but urban sounds produced by cars, motorcycles, trains, and airplanes, in addition to the sounds produced in buildings and industries, are significantly different from most natural sounds because most of their energy is concentrated in low frequencies (below 2000 Hz) and has longer duration (Warren et al., 2006; Brumm, 2006; Slabbekoorn & Ripmeester, 2008). High noise levels can mask animal acoustic signals, such as sounds from reproductive partners, alarm calls, parental care and territorial defense songs (Brumm et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2017). The masking effect can force species to use compensatory mechanisms to vocally communicate or abandon noisy areas (Nemeth & Brumm, 2009; Santos et al., 2017). A common behavioural adaptation employed to overcome masking consists in increasing the amplitude of calls, a response known as Lombard Effect (Brumm & Zollinger, 2011). Additionally, many species have been found to change the features of the calls, such as frequency, duration, number of notes in noisy places (Warren et al., 2006; Duarte et al., 2017; Tolentino et al., 2018). Studies on the impact of noise pollution on animals are important because they can drive the elaboration of management strategies and conservation of urban forests, which are wildlife refuges (Barber et al., 2009; Duarte et al., 2011; Teixeira et al., 2015; Santos et al., 2017).

In the present study, we investigated the soundscape comparing biophony and noise levels (i.e., sound pressure levels) between the border and the centre of a tropical urban forest fragment. We also identified and quantified the number of species calling at both sites. Our hypothesis was that noise and biophony levels would differ significantly between the two sites. We predicted higher levels of biophony and potential species richness where noise was lower.

Materials and methods

General considerations on passive acoustic monitoring (PAM).

Passive acoustic monitoring is a method used in the study of soundscape ecology, both in terrestrial and aquatic environments. Acoustic sensors can record sounds for prolonged periods and produce a massive amount of data. Several acoustic indexes have been developed to optimize data analysis and extract relevant ecological information from such recordings. Among them, the acoustic complexity index (ACI) has the purpose of quantifying biophony by processing the intensities of the vocalizations recorded in audio files, even in the presence of continuous anthropogenic noise (Pieretti et al., 2011). By providing an estimate of the amount of biophony in an environment, the ACI has proven to be a useful tool to evaluate behavioural changes and define the composition of an animal community (Pieretti et al., 2011; Farina et al., 2011a).

Study area. This study was conducted in an urban tropical forest fragment located inside the campus of the Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) of Minas Gerais, in the Northwest Zone of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil (19º55’10 S 43º59’31 W; Figure 1). The elevation of the area ranges from 870 to 930 m above sea level. The PUC forest is a remnant fragment of Atlantic forest of 66 755 m², characterized as a semideciduous seasonal secondary forest with many species of insects, anurans, reptiles, birds (approximately 134 species, see Vasconcelos et al., 2013) and mammals. Currently, this area is surrounded by a densely anthropized urban matrix, which hampers or prevents the dispersal of many species to other fragments. A museum of Natural Sciences, a sport centre and a small airport (Aeroporto Carlos Prates in activity since 1944) are located in the area surrounding the forest fragment (i.e. within 2 km radius).

Figure 1 Sampling points for biophony at the Pontifical Catholic University forest fragment, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. A and B represent the centre, and C and D the forest border .

Data collection. The data were collected using two passive acoustic monitoring sensors (Song Meter Digital Field Recorder -SM2- Wildlife Acoustics, Inc., USA) installed at 1.5 m height above ground level in the central area (points A and B) and other two on the border of the forest fragment (points C and D; Figure 1). To prevent overlap of the sound recorded (i.e., to ensure independence of data sources), the distance between each SM2s in the centre and border stations was 80 meters. The distance between the stations (centre and border) was approximately 300 meters. The distances between the SM2s and roads were 30 meters for the border station and 100 meters for the centre station (Figure 1). Similar distances were tested and published in our previous studies in Atlantic forest areas (Duarte et al., 2015). SM2 were configured to record 24 hours per day, one week per month, during three consecutive months, from May to July 2012. In May, data were collected between the 24th and 31st, in June from the 21st to the 28th, and in July from the 24th to the 31st. The devices recorded by using a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, 36 dB microphone gain, wave format files and on stereo channel using two omnidirectional waterproof microphones with a flat frequency response of 0.020-20 kHz, sensitivity of -36 ± 4 dB and a signal to noise ratio of >62 dB.

We also conducted two 15-minute measurements of the background sound pressure levels once per month at each recording point, using a Z-weighted B&K2270 sound level meter. All the animal sounds close to the microphone were excluded from the recordings using the BZ5503 software (Bruel and Kjaer, Denmark). The equivalent sound levels (Leq), which are the standard for sound-pollution measurements, were then calculated (Rossing, 2007).

Together with noise, species richness and species abundance could influence acoustic differences between border and centre of the forest fragment. Unfortunately, abundance is difficult to evaluate using PAM (Duarte et al., 2015). Therefore, potential species richness was calculated for each site using aural identification (i.e., manual) of animal sounds. This analysis was done using spectrograms created in Raven Pro 1.5 software. One day (24 hours) per recording session was randomly selected from each sampling point for species’ identification surveys. Sounds emitted by insects, anurans, birds and mammals were identified by taxon group specialists who visually and aurally inspected the first three-minutes of every quarter hour. Where the sounds could not be associated to a particular species, they were classified as sound types in order to determine the potential number of species at each site.

Data analysis. All files were processed via the ACI (Pieretti et al. 2011) to obtain a measure of biophony. Anthropogenic noise was quantified using the power spectral density (PSD). ACI and PSD were extracted using Wavesurfer software (Sjölander & Beskow, 2000).

The ACI metrics, like other indices created to operate in soundscape analysis, are based on the fact that there is a strict and direct relationship between the complexity of animal communities, and the spectral and temporal complexity of a soundscape. In other words, the acoustic information expressed by the ACI is greater in a location where there are more individuals and/or more species. (Farina et al., 2011b). The ACI algorithm has already been successfully applied in terrestrial habitats (Pieretti & Farina, 2013; Bobryk et al., 2015), including forest fragments in neotropics (Pieretti et al., 2015; Duarte et al., 2015).

The power spectral density is a quantitative measure of the acoustic energy of the environmental sounds expressed per unit frequency (Duarte et al., 2015). It is commonly used to obtain the distribution of the power across the frequency domain. At low frequencies, the acoustic energies at our study sites were mainly driven by urban noise pollution. Consequently, the PSD was used as an indicator of anthropogenic noise.

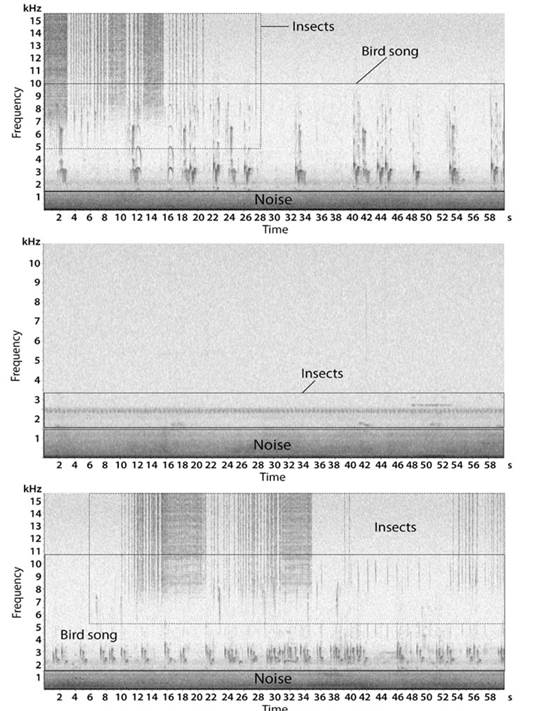

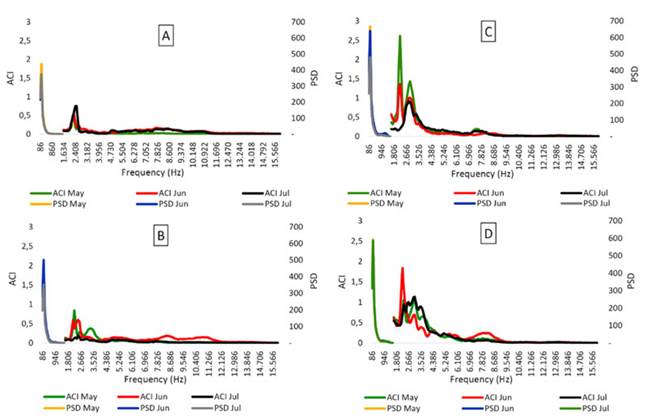

The sampling points were grouped in central area (points A and B) and border area (points C and D). Recordings were subsampled analyzing three minutes of every fifteen minutes, totalizing 403.2 hours. To calculate the ACI, the Fast Fourier Transform-FFT of 512 points was used (frequency bin: 86Hz; temporal step: 0.01s). A one-second grouping value was used, in order to obtain one ACI value at every second for every frequency bin, successively averaged over the lenght of the recording (three minutes). Sounds concentrated below 1550 Hz were measured by summing PSD values in the relative frequency bins (expressed in V2Hz−1). ACI values (from 1550 to 16 000 Hz) were considered as biophony, emitted by insects, birds and mammals (Figure 2). Temporal distribution of both PSD and ACI were carried out.

Figure 2 Spectrograms of the soundscape recorded at the border of the Pontifical Catholic University forest fragment, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.. Frequencies below 1550 Hz are filled by noise and biophony (insects, and bird songs) was concentrated between 1550 to 16000 Hz.

The data of ACI and PSD did not present normal distributions. Therefore, a log transformation was performed to remove the effects of magnitude differences between variables, avoiding negative numbers, normalizing the data and increasing the importance of the smaller values (Manly, 1997). Subsequently, Pearson’s correlations and ANOVA tests (Dunn post hoc test) were performed.

Results

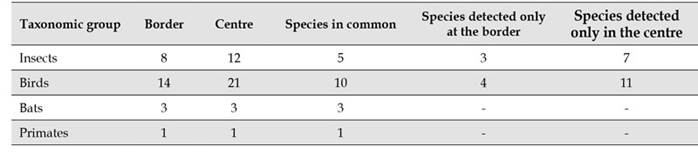

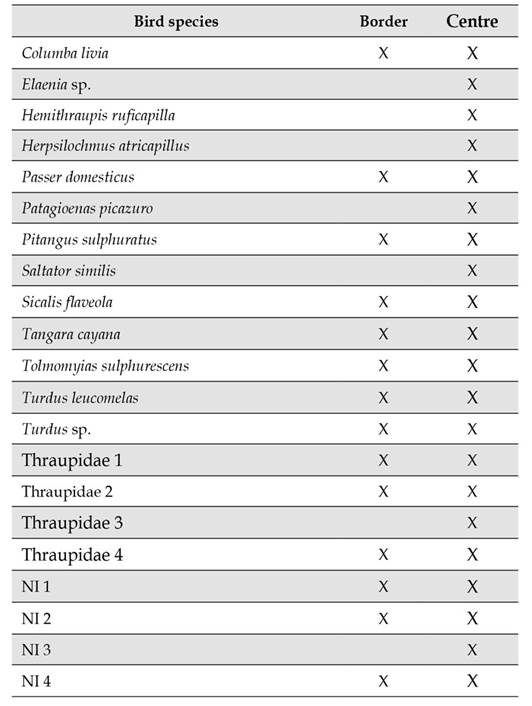

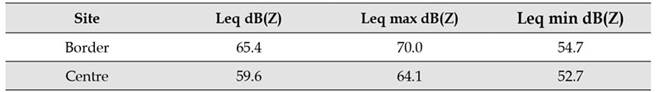

The soundscape of the study area was dominated by biophony and anthropogenic noise. Biophony was emitted by 12 potential insect species, 21 of bird taxa, one marmoset species (Callithrix penicillata) and three potential species of bats (Tables 1 and 2). The main noise sources affecting the area came from a small airport, vehicular traffic, and from the nearby university (Table 3). Some of the noises identified were: helicopters, airplanes, sirens, horns, motorcycles, sports games, lawnmowers and people’s conversations.

Table 1 Potential number of species at border and centre sites of an urban tropical forest fragment in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Southeast Brazil.

Table 2 Bird species recorded by passive acoustic monitoring at an urban forest fragment in Minas Gerais, Southeast Brazil. NI, unidentifed species.

Table 3 Mean noise (sound pressure) level at the border and the centre of an urban tropical forest fragment in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Southeast Brazil.

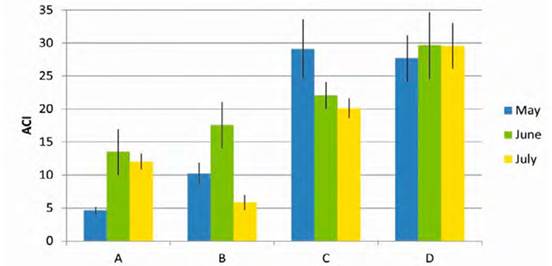

Biophony. ACI was significantly higher at the border than at the centre of the forest (F = 83.6, DF = 1, MS = 3.86, P < 0.01; Figure 3). No significant difference was found between the months sampled (F = 1708, DF = 2, MS = 0.145, P = 0.18).

Figure 3 Biophony values (Acoustic Complexity Index-ACI) in the centre (A and B) and in the border (C and D) of the Pontifical Catholic University forest, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

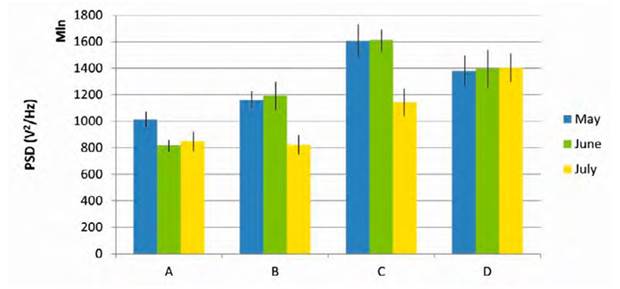

Biophony vs noise. The border of the forest fragment presented both higher noise values (i.e. PSD) and greater biophony (i.e. ACI) in relation to the centre. The ACI and PSD values presented a medium strength positive correlation, demonstrating that the higher the noise, the greater the biophony (r = 0.56; N = 96, P< 0.01; Figure 5).

Figure 4 Biophony (ACI) and noise (PSD) values distributed across frequency bands for the sites in the centre (A and B) and border (C and D) of the Pontifical Catholic University forest, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Figure 5 Noise values (Power spectral density-PSD) in the centre (A and B) and in the border (C and D) of the Pontifical Catholic University forest fragment, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Potential species richness. Acoustic diversity of sound types was found to be higher at sampling points in the centre of the forest fragment (Table 2).

Noise - Equivalent levels (Leq). As expected, noise levels were higher on the border (Leq max 70 dB (Z)) than in the central area (Leq max 64.1 dB (Z); Table 3).

Noise - Power Spectral Density (PSD). Accordingly, PSD values at the border were significantly higher than in the centre of the forest fragment (F = 85.67, DF = 1, MS = 0.657, P <0.01; Figure 5). PSD varied between months both in the centre and in the border, being significantly lower in July (F = 5.94, DF = 2, MS = 0.07, P <0.05).

Discussion

Our findings can be interpreted as changes in the acoustic behaviour of species due to noise, but they could also be the result of species segregation by degree of vocal plasticity (i.e. ability to adapt) or even of differences in composition of communities.Our results showed that background noise is almost 6 dB (Leq) higher at the border points. In acoustics, an increase of 3 dB doubles the sound intensity (Rossing, 2007). Higher noise levels at the border of the forest were expected due to the vicinity of sound sources, such as streets and buildings. Other studies have obtained similar results in Southeast Brazil, recording higher noise values on the border of an urban park (Duarte et al., 2011) and in an Atlantic forest fragment (Duarte et al., 2015; 2017). This result may be due to many factors, for example, higher abundance of individuals at the border, or an attempt by animals to use compensatory mechanisms to communicate in noisy areas.

Since we found a higher number of sound types in the centre of the forest, which suggests higher species richness, it is likely that the animal community at the border has changed its vocal behaviour by increasing amplitude, and/or the calling rate and duration of their calls as a form of adaptation to compensate for the noise. Studies with birds and mammals have shown that animals are able to increase the amplitude of their vocalizations in noisy areas; this is known as the Lombard Effect (Cynx et al., 1998; Brumm et al., 2004; Brumm & Slater, 2006). Our previous study on the effects of mining truck traffic on cricket calling activity showed that species in noisy sites emit calls with higher average power, an indicator of sound intensity levels (Duarte et al., 2019).

Since the ACI uses the variation of amplitude in each frequency band to calculate biophony, the increase in the amplitude of vocalizations can generate higher values of this index (Zhao et al. 2019). Other types of noise compensatory mechanisms such as repetition of notes, syllables, increased call rate might also influence the values of the ACI (Brumm et al., 2004; Sun & Narins, 2005). Other studies have found animals exhibiting greater acoustic activity in noisier areas. Pieretti & Farina (2013) showed that both ACI values and noise were significantly higher with increasing proximity to a road, suggesting a more active singing/vocalising community in those sites where noise was more intense. Duarte et al., (2015) also found higher ACI values throughout the day in a noisy area, despite having less species compared to a silent area, indicating the possible use of compensatory mechanisms to communicate in presence of noise.

The direct energetic cost of vocal behaviour includes the energy required to produce the sound as well as the energy lost by not feeding during the time spent in vocalizations (Deecke et al., 2005). However, the indirect costs of acoustic communication include the possibility of passing information to unwanted receivers, such as competitors (Hammond & Bailey 2003), predators (Hosken et al., 1994; Mougeot & Bretagnolle, 2000) and parasites (Muller & Robert, 2002). A study found that an urban bird can vocalize up to 70 dB in response to varying noise levels (Díaz et al., 2011). However, vocal activity declined sharply above the threshold of 70 dB, which suggests that this strategy is costly for birds. This study further suggests that bird populations in noisy environments, such as cities, may face a greater challenge for survival compared to those in quiet areas, even for species that can mitigate the interference of urban noise in their acoustic communication (Díaz et al., 2011). Thus, in our study it is possible that animals were spending excessive energy in their communication.

Pieretti & Farina (2013) consider the possibility of birds remaining segregated between noisy and silent areas based on their vocal plasticity and on the ability to increase their song production. Thus, individuals genetically predisposed to produce intense vocalization behaviour can tolerate anthropogenic noise and live in noisy places, while others that are more sensitive to noise prefer to live in quieter areas. It might be possible that the animals that vocalized on the border of our study site were more noise tolerant and thus continued vocalizing, despite high levels of anthropogenic noise. However, it is also possible that the higher biophony at the border was related to a difference in animal community compositions between the border and the centre of the forest. Greater species richness singing at the border would also be responsible for a greater acoustic activity at the border. However, we found higher diversity of sound types in the centre of the forest, where biophony was lower. Similar results were found close to an open-cast mine in Brazil (Duarte et al., 2015). Studies on the edge effect in a community of birds indicate that there is a tendency for lower species richness and density at the edges of forests (Kroodsma, 1982; Laurance, 2004). Perillo et al., (2017) found lower bird species richness in areas with higher noise levels in urban green areas in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. These evidences do not support the hypothesis that higher levels of biophony in our border sites might be linked to higher species richness or abundance.

In our study, we registered lower noise levels in July compared to other months. Indeed, this month corresponds to the university’s major vacation period, with less students attending the nearby sport centre and, consequently, less noise produced by cars and buses, whistles, sport noises and people talking. Contrarily, biophony values did not vary over the three months of data collection. Since the data were collected during three months of the same season (dry), we did not expect variation in acoustic activity of the animals during the months studied.

Our findings showed that the impact of noise on the fauna can be acoustically monitored by measuring altered biophonic activity. Our results show how the relation between biophony, soniferous species richness, and anthropogenic noise is complex, mainly at a local scale. We suggest the use of ecoacoustics for future studies since it can be useful for interpreting anthropogenic disturbances and help the development of adequate urban management and conservation strategies.