Introduction

Psychodidae are insects of the order Diptera (suborder Nematocera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae), belonging to the family Psychodidae and the subfamily Phlebotominae (Young and Duncan, 1994). Phlebotomine sandflies are the main vectors of parasites of the genus Leishmania spp. that cause a zoonotic disease known as leishmaniasis that presents diverse clinical manifestations and its transmission occurs in tropical and subtropical areas, being endemic in 98 countries (Alvar et al., 2012; Ferro et al., 2015). There are 350 million people at risk of leishmaniasis and it is estimated that about 900,000 - 1.3 million new cases of leishmaniasis are reported each year (Pan American Health Organization [PAHO], 2023).

It is important to mention that, in Antioquia, Porter conducted the first inventory study of phlebotomine sandflies in the area of influence of the Providencia hydroelectric plant located in the municipality of Anorí in 1970. In that study, four species of the genus Lutzomyia (Lu. hartmanni, Lu. gomezi, Lu. trapidoi and Lu. yuilli) and one of the genus Warileya (Wa. rotundipennis) were recorded (Porter and DeFoliart, 1981).

Another study was conducted between 1997 and 2000 by the Epidemiological Surveillance System Group (SVE) of the University of Antioquia at the Porce II hydroelectric plant, where eight Lutzomyia species (Lu. barretoi, Lu. lichyi, Lu. gomezi, Lu. shannoni, Lu. panamensis, Lu. triramula, Lu. carrerai and Lu. walkeri) were reported (Zuluaga et al., 2012). This group also conducted studies from 2007 to 2009 in the Porce III Hydroelectric Project, reporting 13 species of Lutzomyia (Zuluaga et al., 2012).

In 2003, at the ISAGEN dams in the municipality of San Carlos in Antioquia, the Colombian Institute of Tropical Medicine (ICMT) conducted a focus study, recording the species Lu. panamensis, Lu. gomezi, Lu. bifoliata and Wa. Rotundipennis. Based on the abundance found in the sampling sites, anthropophilic behavior and vectorial antecedents, it was suggested that Lu. panamensis and Lu. gomezi are responsible for the transmission of the parasite that causes cutaneous leishmaniasis in this area (Parra-Henao and Echavarría, 2005).

In 2008 in the department of Caldas, a study of leishmaniasis outbreaks was reported in the hydroelectric plant La Miel I in the sectors of Guarinó and Manso. Five species of Lutzomyia were found (Lu. longipalpis, Lu. gomezi, Lu. trapidoi, Lu. trinidadensis and Lu. cayennensis) (Vergara et al., 2008). Another study conducted in this same plant in 2013 reported for the first time the maximum altitude of distribution of Lu. longipalpis at 1350 m.a.s.l. (Acosta et al., 2013).

In 2012 in the municipality of Chaparral (Tolima) in the area of influence of the Amoyá hydroelectric project (2008-2009), 13 species of phlebotomine sandflies were identified, of which the species Lu. longiflocosa, Lu. columbiana, Lu. nuneztovari, Lu. suapiensis and Wa. rotundipennis are epidemiologically important and Lu. longiflocosa has been recorded as a carrier of Leishmania braziliensis (Contreras et al., 2012).

In the department of Santander, during studies conducted in 2016 and 2017 in the Sogamoso hydroelectric power plant, 21 species of Lutzomyia were recorded, highlighting the presence of Lu. gomezi, Lu. panamensis and Lu. ovallesi as important transmitter species of parasites that cause cutaneous leishmaniasis. The species Lu. longipalpis, which transmits Leishmania species that cause visceral leishmaniasis, was predominant (Gómez-Vargas and Zapata-Úsuga, 2022).

Finally, in 2016 in the Urra hydroelectric plant, the presence of 12 species of Lutzomyia were reported, where it was also found that seven were naturally infected with Leishmania spp. (Lu. panamensis, Lu. gomezi, Lu. cayennensis, Lu. micropyga, Lu. shannoni, Lu. trinidadensis and Lu. yuilli yuilli). Records for five new species in the department of Córdoba (Lu. carpenteri, Lu. dysponeta, Lu. atroclavata and Lu. yuilli yuilli) were also reported (Vivero et al., 2016).

In the New World, phlebotomine sandflies are involved in the propagation of protozoa of the genus Leishmania Ross, 1903, (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) (Akhoundi et al., 2016; Lainson and Shaw, 1973; Vivero et al., 2015). Phlebotomine sandflies can also propagate arboviruses of the Bunyuviridae family where the Flebovirus genus stands out, represented mainly by the phlebotomine fever (known as Panama fever in the New World and "pappataci fever" in the Old World) and arboviruses of the Rhabdoviridae family represented by the Vesiculovirus genus (which produces Chandipura virus encephalitis), summer meningitis (Toscana virus), vesicular stomatitis (called New Jersey stomatitis or Indian stomatitis), which affect cattle, horses, swine and humans. Additionally, phlebotomine sandflies transmit other pathogens such as the bacterium Bartonella bacilliformis that produces Carrion's disease (Acevedo and Arrivillaga, 2008; Maroli, et al., 2013; Vivero et al., 2015; Young, 1977). Disease transmission is due to the hematophagous behavior of females which need the blood of their endothermic vertebrate hosts (cattle, dogs, rodents and man) (Sales et al., 2015; Sant'Anna et al., 2008; Tanure et al., 2015) and exothermic vertebrates, such as reptiles and amphibians (Abbate et al., 2020; Young and Duncan, 1994), to carry out their gonotrophic cycle. Males feed preferentially on sugars produced by plants or by aphids and/or coccidia and females supplement their diet with these sugars (Bastidas et al., 2004; Cameron et al., 1994). Phlebotomine sandflies are considered telmophages, because they lacerate the skin of the animal using their mandibles, causing a small accumulation of blood from which they feed (Gonzalez, 2019).

There are 1000 species of phlebotomine sandflies, 535 which have been recorded in the Americas (Galati, 2018) and approximately 45 being vectors of different species of Leishmania (Cecílio et al., 2022; Gradoni, 2018). In Colombia, 167 species have been described (Ferro et al., 2015), 153 which are part of the genus Lutzomyia (Bejarano and Estrada, 2016), 14 of which are confirmed as vectors, and an additional eight as potential vectors (Gómez-Vargas and Zapata-Úsuga, 2022; Méndez- Cardona, 2021).

The species confirmed as vectors in Colombia are the following: Lu. columbiana (Bejarano et al., 2003; Grimaldi et al., 1989; Montoya-Lerma et al., 1999; Pan American Health Organization [PAHO], 2012), Lu. evansi (Bejarano et al., 2002; Bejarano et al., 2003; PAHO, 2012; Travi et al., 2001; Urango and Hoyos-López, 2022), Lu. gomezi (Alexander et al., 2001; Bejarano et al., 2002; Montoya-Lerma et al., 1999), Lu. hartmanni (Alexander et al., 2001; Grimaldi et al., 1989), Lu. lichyi (Alexander et al., 1995; Warburg et al., 1991), Lu. longiflocosa (Bejarano et al., 2003; Cárdenas et al., 1999; Méndez-Cardona, 2021; Pardo et al., 1999), Lu. longipalpis (Corredor et al., 1989, 1990; Goenaga-Mafud et al., 2020), Lu. ovallesi (Alexander et al., 2001; Bejarano et al., 2003), Lu. panamensis (Alexander et al., 1995; Bejarano et al., 2003), Lu. scorzai (Alexander et al., 1995), Lu. spinicrassa (Morales et al., 2005), Lu. trapidoi (Alexander et al., 2001; Corredor et al., 1990; Martínez et al., 2018; Santamaría et al., 2006, Travi et al., 1988), Lu. umbratilis (Grimaldi et al., 1989), and Lu. yuilli yuilli (Martínez et al., 2018; Santamaría et al., 2006).

The potential vectors are the following: Lu. antunesi (Niño and Pérez-Español, 2021; Vásquez-Trujillo et al., 2008), Lu. davisi (Bejarano et al., 2006), Lu. flaviscutellata (Cabrera et al., 2009; PAHO, 2012), Lu. hirsuta hirsuta (Cabrera et al., 2009; Ministerio de Protección Social [Minsalud], 2010), Lu. torvida, Lu. townsendi (Bejarano et al., 2003), Lu. trinidadensis (Vivero et al., 2017) and Lu. quasitownsendi (Bejarano et al., 2003; Garcia-Leal et al., 2020).

For the municipalities in the area of influence of the Ituango hydroelectric power plant, the first records of leishmaniasis began in 1995 in municipalities in the northern subregion such as Briceño (eight cases), Ituango (10 cases), and Valdivia (38 cases). In the western subregion, only one case has been recorded in Sabanalarga. For the department, 895 cases were recorded that same year (Dirección Seccional de Salud de Antioquia [DSSA], 1998). In 1997, the department registered 951 cases of leishmaniasis, including municipalities in the area of influence of the Ituango hydroelectric power plant such as Briceño (2 cases), Ituango (44 cases), Valdivia (70 cases), and Santa Fe de Antioquia (one case) (DSSA and Laboratorio Departamental de Salud [LDS], 1998). Between 1998 and 2001, there are no records for these areas.

In 2002, some municipalities in the study area were considered endemic for leishmaniasis, such as the municipality of Valdivia in the northern subregion, which registered 1825 cases of leishmaniasis between 2002 and 2011, and 1198 cases between 2012-2020. This is followed by Ituango (785 cases between 2002-2011 and 464 cases from 2012 to 2020), Briceño (204 cases from 2002 to 2011 and 121 cases from 2012 to 2020). For the municipalities of the western sub-region, Santa Fe de Antioquia recorded the most cases with a total of 458 distributed as follows: 52 cases from 2002 to 2011 and 406 cases from 2012 to 2020. Other municipalities in this subregion that reported cases were Sabanalarga (8 cases 2002 to 2011 and 284 cases from 2012 to 2020) and Buriticá (4 cases from 2002 to 2011 and 131 cases from 2012 to 2020) (DSSA, 2011, 2020). Because of this, the northern subregion of the department of Antioquia is considered to be high incidence and endemic for leishmaniasis, especially the municipalities of Briceño, Ituango and Valdivia, the latter, where focus studies have been conducted (Posada-López et al., 2014).

Materials and methods

Study area

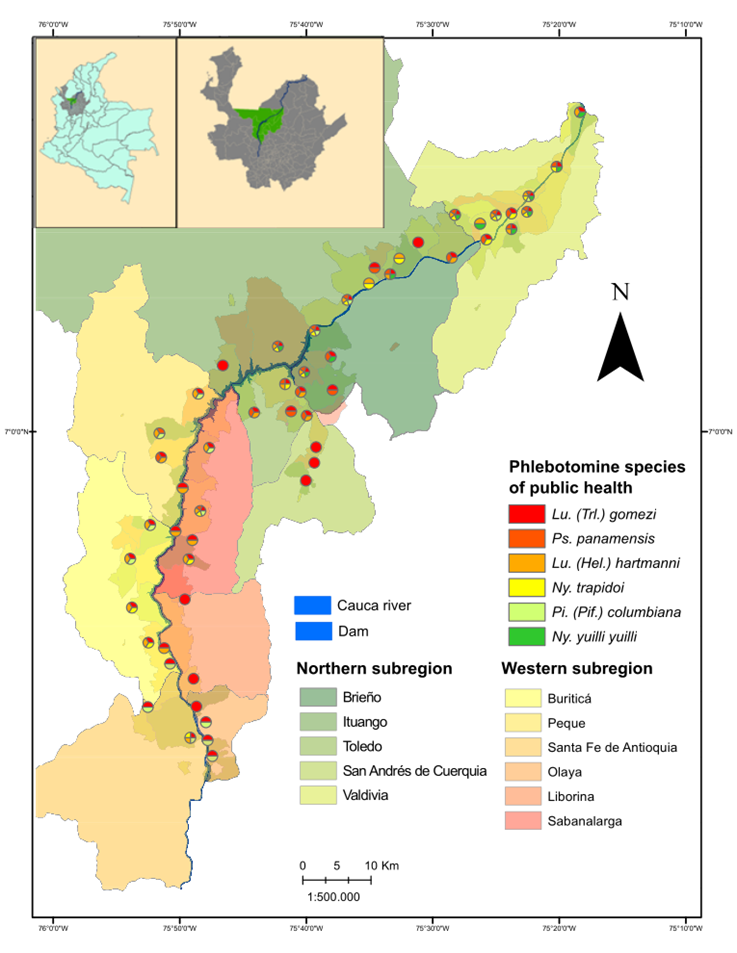

The study was conducted in the rural area of the western subregion of the municipalities of Buriticá (6°43′12″N, 75°54′27″O), Liborina (6°40′41″N 75°48′44″O), Olaya (6°37′40″N 75°48′43″O), Sabanalarga (6°50′54″N 75°49′01″O), Peque and Santafé de Antioquia (6°33′23″N 75°49′39″O) and in the northern subregion in the municipalities of Briceño (7°6′38″N, 75°33′4″O), Valdivia (7°09′49″N 75°26′21″O), Ituango (7°10′16″N 75°45′49″O), San Andrés de Cuerquia (6°54′52″N 75°40′33″O) and Toledo (7°00′37″N 75°42′06″O), municipalities where the Hidroituango project is being executed (Figure 1). These municipalities are located in the Cauca River canyon between the central and western mountain ranges, and have two ecotopes, a dry forest type fragmented mainly with coffee and cocoa crops in the western subregion, while the northern subregion is dominated by tropical rainforest, predominantly gallery forest, coffee, cocoa and illicit crops.

Entomological sampling

Sampling was carried out during two nights at each site, with a CDC type light trap between 18:00 and 06:00 hours located in the intra, peri and extradomicile, and with a Shannon trap between 18:00 and 21:00 using a mouth aspirator. Monitoring was conducted every three months for eight consecutive years (years 2012-2020), including dry and rainy seasons. All specimens collected were stored in 1.5 ml tubes, with 70% alcohol, subsequently rinsed with 10% KOH. Hoyer's liquid was used for semi-permanent mounts. For taxonomic identification, the dichotomous keys of Young (1977, 1979), Young and Duncan (1994) and Galati (Galati, 2018; Galati et al., 2017) were used.

An Excel database was used for the calculations of entomological indicators for the species of medical importance. Past 3 software was used for the statistical analysis of diversity and Arcgis 10.1 and Maxent 3.4.4 software was used for the projection of species and maps.

Results

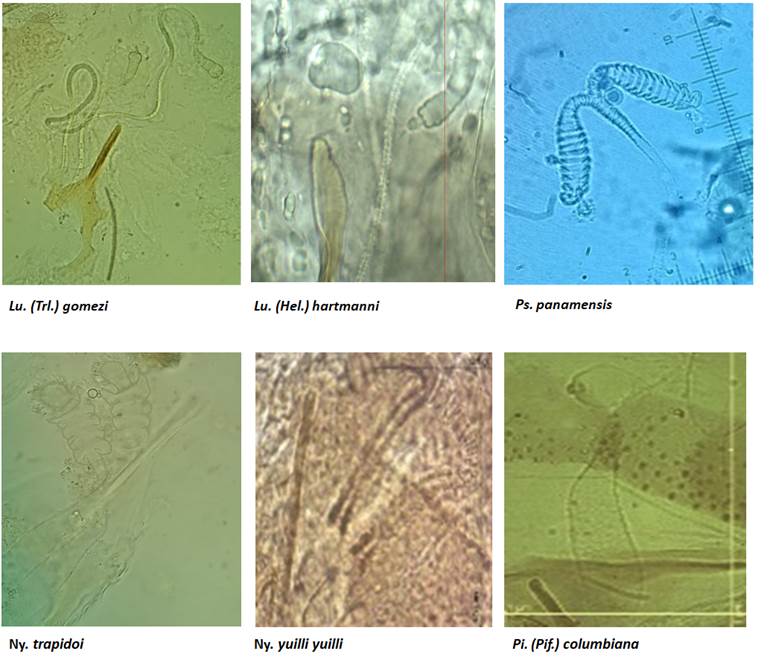

A total of 7993 phlebotomine sandfly specimens were identified (5469 specimens for the municipalities of the northern subregion and 2524 for the municipalities of the western subregion), distributed in 39 species belonging to 13 genera according to Galati's classification (Galati, 2018; Galati et al., 2017). The abundance and total number of specimens collected per municipality according to the subregion to which that municipality belongs is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Abundance of phlebotomine sandfly species collected in the ten municipalities located in the area of influence of the Ituango Hydroelectric Project, Antioquia between 2012-2020.

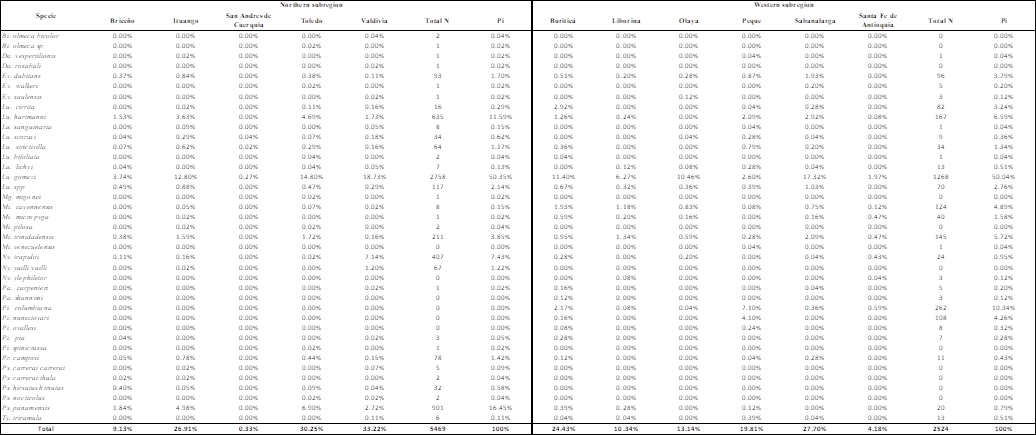

Of the species collected in the sampling area (Table 1), six are implicated in the transmission of parasites of the genus Leishmania in Colombia: Lu. (Trl.) gomezi, Lu. (Hel.). hartmanni, Ps. panamensis, Pi. (Pif.) columbiana, Ny. trapidoi and Ny. yuilli yuilli yuilli. Figure 2 shows the spermathecae of these species as a morphological character of importance.

Figure 2 Spermathecae of phlebotomine sandfly species of epidemiological importance collected in the area of influence of the Ituango Hydroelectric Project, Antioquia.

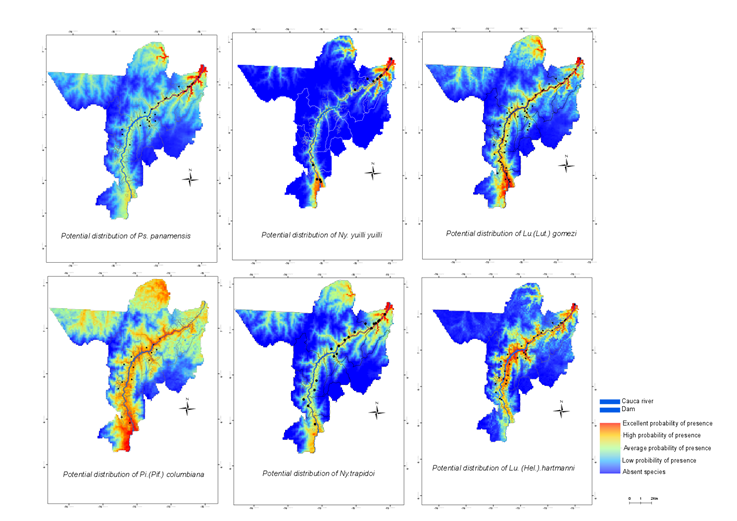

Given the epidemiological importance of these vector species, potential distribution maps were constructed in MaxEnt (Figure 3). For the analysis of the spatial distribution of the six species, 90 georeferenced points were used. For the construction of the predictive models with MaxEnt, 21 bioclimatic variables which correspond to environmental layers in raster format for the area were used with a resolution of 30 seconds (1 km). Monthly mean precipitation and temperature data were taken from the Worldclim database (worldclim, 2020). The variables used were the following: BIO1, annual average temperature (°C); BIO2, diurnal range of temperature (°C); BIO3, isothermality (°C); BIO4, seasonality of temperature (°C); BIO5, maximum temperature of the hottest period (°C); BIO6, minimum temperature of the coldest period (°C); BIO7, annual range of temperature (°C); BIO8, average temperature in the rainiest quarter (°C); BIO9, average temperature in the driest quarter (°C); BIO10, average temperature in the hottest quarter (°C); BIO11, average temperature in the coldest quarter (°C); BIO12, annual precipitation (mm); BIO13, precipitation in the rainiest period (mm); BIO14, precipitation in the driest period (mm); BIO15, seasonality of precipitation (%); BIO16, precipitation in the rainiest quarter (mm); BIO17, precipitation in the driest quarter (mm); BIO18, precipitation in the hottest quarter (mm); and BIO19, precipitation in the coldest quarter (mm). Topographic and ecological variables could not be included in this study.

Figure 3 Potential distribution of phlebotomine sandflies of epidemiological importance in the area of influence of the Ituango Hydroelectric Project, Antioquia.

The collected species Lu. (Hel.) sanguinaria (Fairchild and Hertig, 1957), Mg. (Mig.) migonei (França, 1920), Pi .(Pif.) spinicrassa (Morales et al., 1969) and Pi. (Pif.) moralesi (Young, 1979) correspond to new records for the department of Antioquia, thus expanding the geographical expansion of these species in the country.

In addition, five species were collected using human bait, suggesting that they have anthropophilic habits. These were: Lu. (Lut) lichyi; for which this behavior has already been recorded in the Cauca valley (Alexander et al., 2001) and in Venezuela (Cazorla-Perfetti, 2015). Lu. (Hel.) strictivilla; a species that according to Young, feeds on humans (Young, 1979). Mi. (Sau.) trinidadensis; reported to have a feeding preference for geckos and lizards (Young, 1979), although it has been reported to bite humans in the Colombian Orinoquia (Vivero et al., 2010). Ev. (Ald.) dubitans is considered saurophilous (Young and Duncan, 1994), but in Colombia there are reports of it biting humans in the Montes de María (Cortés et al., 2009). Finally, Lu. (Hel.) cirrita, recorded in southwestern Colombia in Alto Anchicayá (Valle del Cauca) and reported in human baiting (Barreto et al., 1997)..

Discussion

This research determined the diversity and abundance of phlebotomine sandfly species present in the rural areas of the Cauca River canyon, which are part of the Ituango hydroelectric project. It was also possible to update the inventory of epidemiologically important species as vectors of leishmaniasis in these municipalities.

In addition, the presence and wide dispersion of species reported in the literature as vectors of Leishmania species that cause cutaneous leishmaniasis was verified: Lu. (Trl.) gomezi, Lu. (Hel.) hartmanni, Ps. panamensis, Ny. trapidoi, Ny. yuilli yuilli and Pi. (Pif.) columbiana. It is important to note that this research presents new records of Lu. (Hel.) sanguinaria, Mg. (Mig.) migonei, Pi. (Pif.) spinicrassa and Pi. (Pif.) moralesi for the department of Antioquia. However, theses species have not been incriminated in the transmission of the parasite to date.

The results show that in both subregions the dominant species present in all sampling points was Lu. (Trl.) gomezi, which presented a Pi = 50.04 for the western subregion and a Pi = 50.35 for the northern subregion. This species was collected in extra, peri and intradomiciliary, in protected human bait and in Shannon traps.

The behavior of Lu. (Trl.) gomezi is consistent with that reported by other authors, which shows that this species could easily adapt to different environments due to a high degree of adaptability (Niño and Pérez-Español, 2021). At the same time it is the most widely distributed species in Colombia, being registered in 24 departments (Bejarano, 2006; Bejarano and Estrada, 2016; Ferro et al., 2015). In addition, this species has been recorded in different hydroelectric power plants in the country, since the work carried out by Porter, in 1970 in the Providencia hydroelectric power plant (Porter and DeFoliart, 1981) to later works such as in the Porce II-III hydroelectric power plant (Zuluaga et al., 2012) at Isagen-San Carlos (Parra-Henao and Echavarría, 2005) at the Sogamoso hydroelectric power plant (Gómez-Vargas and Zapata-Úsuga, 2022) and in the La Miel I hydroelectric power plant (Veléz-Bernal et al., 1999). In relation to works carried out in other countries, where there are records of important species, Brazil reports the presence of Lu. (Trl.) gomezi in the Usina Luís Eduardo Magalhães hydroelectric power plants (Vilela et al., 2011) and in the Santo Antônio do Jari hydroelectric system (Furtado et al., 2016). It is also important to highlight that in Colombia, Lu. (Trl.) gomezi is the most important vector in the transmission of L. panamensis and L. brazilensis (World Health Organization, 2012) which cause cutaneous leishmaniasis (INS, 2019). Regarding the other species of importance, there are reports of Lu. (Hel.) hartmanni and Ny. trapidoi in the Toaschi- Piltaón hydroelectric plant in Ecuador, where their abundance implies that Ny. trapidoi is responsible for the transmission of leishmaniasis cases in the area (León et al., 2014).

Since 1997, the Cauca river canyon, especially the northern sub-region, has been an area where, before the construction of the Hidroituango project began, some of its municipalities have registered cases of leishmaniasis and is considered endemic by the VTE control and prevention program of the Health Department of Antioquia, which is why it is justified to conduct other studies on this entomofauna in the area.

Some species were collected only in a specific subregion, such as Pi. (Pif.) columbiana, which was collected only in the western subregion where tropical dry forests predominate. This species has been associated with L. mexicana transmission in an outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the southwestern part of the country (Cárdenas et al., 1999; Montoya et al., 1999) and is distributed from the Western and Central Cordilleras to the steppe zones of La Guajira, in a wide altitudinal range from 100 to 2700 m.a.s.l. (Bejarano et al., 2003). Ny. yuilli yuilli was only collected in the northern subregion where tropical rainforest predominates. As for its bionomics, it has been recorded in eight departments, namely: Amazonas, Antioquia, Caquetá, Chocó, Guaviare, Meta, Putumayo and Santander (Bejarano, 2006).

When analyzing the bioclimatic variables with the species of epidemiological importance, it can be observed that they are associated with the biological corridor of the Cauca River, where there are points of higher concentration, indicating a greater probability of collecting them. This is related to the areas of the Cauca River canyon that are critical for leishmaniasis, as can be seen in Figure 3, where the area in red represents the places with the greatest presence of these phlebotomine sandflies and which are important in the transmission casuistry.

Conclusions

In general, we can conclude that the area of the Cauca River canyon where the Ituango hydroelectric project is being executed is an area where phlebotomine sandflies are present, where there are species that are involved in the transmission of Leishmania species that cause cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which is confirmed by the presence of patients who have registered this disease.

Of the 55 species reported for the department (Bejarano and Estrada, 2016), 39 species of phlebotomine sandflies were found in the study area and at least six species are confirmed vectors of parasite transmission: Lu. (Trl.) gomezi, Lu. (Hel.). hartmanni, Ps. panamensis, Ny. trapidoi and Ny. yuilli yuilli and Pi. (Pif.) columbiana.

Based on the abundance of phlebotomine sandflies of public health interest found in the sampling sites, and the endemic nature of the disease in some of the municipalities, it remains an area of great epidemiological importance for the transmission of Leishmania species that cause cutaneous leishmaniasis, with Lu. (Trl.) gomezi standing out as a possible main vector, due to its great abundance in the northern and western subregion. However, the vectorial role of this species as well as that of other important species is not clear, nor are the transmission dynamics of each one; future systematic studies are needed to resolve these concerns and to design appropriate control strategies.