Introduction

Polychaetes comprise a group of annelids (segmented worms) that possess lateral fleshy extensions or parapodia bearing several chitinous bristles or setae from which its name is derived. Although Polychaeta is paraphyletic (Struck, et al., 2011; Purschke, et al., 2014; Weigert, et al., 2014), the term "polychaetes" is still used as a reference for taxonomic purposes (Dean, 2012; Tovar-Hernández, et al., 2014). Polychaetes are abundant and diverse in marine benthic environments (Seaver, 2003) where they play a critical role as part of processes such as bioturbation, recycling of nutrients, and transference of energy to upper levels in the trophic web (Hutchings, 1998). On the other hand, they are considered as good bioindicators, especially of the contamination produced by organic matter and heavy metals (Dean, 2008).

Despite their importance, the biodiversity of polychaetes has not been completely assessed. The low sampling effort in some regions and the misidentifications made by inexperienced taxonomists make it difficult to assess with certainty the number of species and their distribution (Salazar-Vallejo & Londoño-Mesa, 2004; Dean, 2012). Furthermore, compiling information is a difficult task due mainly to the lack of updated checklists and the large quantity of information published in journals with a restricted or regional distribution. Colombia holds an important representation of the Polychaeta fauna recorded in the Caribbean (Miloslavich, et al., 2010), and in that context, we are presenting an updated checklist of polychaetes to contribute a more accurate estimate of the number of species known in the Caribbean coast of the country.

Materials and methods

An updated list of polychaete records for the Caribbean coast of Colombia is presented (Table 1S, https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/802/2624). The information was gathered from 59 formal publications (scientific journals or books) including the most recent list of species (Báez & Ardila, 2003) and ecological papers. All the species names and taxonomic authorities were corroborated against the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) database. The checklist includes the current valid names, synonyms, bathymetric ranges, habitat, and distribution for each species. A bathymetric range of 0 to 2 meters was assigned to those species recorded from mangroves. For records based on misidentifications, a superscript number was added to the reference indicating the author(s) who corrected the identification following the numbering of table 2S, https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/802/2625. We kept the records of genera and species complexes in the list as they were reported; their validity, taxonomic status, and the confirmation of their presence in the region could be the purpose of further studies. This checklist is based on records made before September 2019. Additionally, we are presenting tables and graphics with the cumulative number of recorded species for each ecoregion.

Results

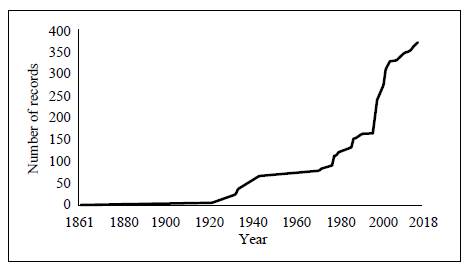

Historical review of Polychaeta richness. The former species Mastigonereis heterodonta, currently valid as Nereis (Perinereis) heterodonta, was the first and only polychaete recorded for Colombia during the 19th century (Schmarda, 1861). In the 20th century, the results of enormous oceano-graphic surveys, particularly the Museen von Leiden und Amsterdam (Augener, 1922; 1933a, b, c; 1934) and the Allan Hancock (Hartman, 1944) expeditions, were important contributions to the knowledge of polychaete fauna in the Caribbean, including some records for the coast of Colombia. Also in the same century, many foreign researchers also made important contributions (Zibrowius, 1969; Southward, 1972; Fauchald, 1973; Kirsteuer, 1973; Dexter, 1974). In the late 70s and the beginning of the 80s, Colombian researchers emerged with some checklists and ecological studies (Palacios, 1978; Victoria & Pérez, 1979; Rodríguez-Gómez, 1979; Dueñas, 1981). Since then, there has been a significant increase in the knowledge of polychaete diversity (Figure 1), particularly due to the contribution of Dueñas (1999), who made almost 250 reports of polychaetes for the Caribbean coast of the country.

Figure 1 Cumulative curve of the number of new polychaete records along the Caribbean coast of Colombia

Laverde-Castillo & Rodríguez-Gómez (1987) compiled a list of species for the Caribbean coast of Colombia and contributed with 11 new records. Almost two decades later, Báez & Ardila (2003) made a new checklist with 35 additional records. To date, it has not been possible to establish an accurate number of species for the Caribbean coast of Colombia, which has sometimes been overestimated by the addition of species recorded from unconventional literature and the inclusion of morph-species and frequently underestimated by the omission of some records from ecological articles. A comprehensive historical review was published by Londoño-Mesa (2017).

In the last 15 years, the number of new polychaetes reports increased by almost 20% with a rate of about four new records per year. Herein we present an updated checklist of polychaetes for the Caribbean coast of Colombia until September 2019. A total of 51 families, 230 genera, and 293 species have been recorded (Table 1S, https://www.raccefyn. co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/802/2624). This number does not include nine species previously recorded as cf. (Victoria & Pérez, 1979; Báez & Ardila, 2003; Lagos, et al., 2018) and one species, Neoamphitrite amphitrite, considered questionable due to the lack of records in WORMS or in any other database. The family Eunicidae was best represented with 33 species (11.3%), followed by Syllidae with 23 species (7.8%) and Nereididae with 19 species (6.5%) (Figure 2). The family Longosomatidae was recorded in an ecology paper (Guzmán-Alvis & Solano, 1997) without mentioning a specific genus. Twenty-one species found in Colombia have been new to science, however, one has been invalidated (Eupanthalis oculataHartman 1944 now Zachsiella nigromaculata (Grube, 1878), as it was considered a subjective synonym.

Habitat and spatial and bathymetrical distribution. The Caribbean coast of Colombia is divided into nine strategic ecoregions according to environmental, social, cultural, and political dimensions; six are continental, two insular, and one oceanic (Díaz & Gómez, 2000). The Tayrona ecoregion is one of the smallest in coastal extension, however, 32% of all polychaetes have been recorded there. The Magdalena ecoregion is second in richness with 23.4%, and the insular ecoregion (San Andrés and Old Providence), as well as the Guajira Ecoregion, each with 11.2% of the records, are third (Figure 3). Polychaetes in Colombia have been found inhabiting in mangroves, seagrass, and even as parasites and commensal of sponges, ascidians, crinoids, bivalves, and other polychaetes; they have also been found in artificial substrates such as wrecks, woodpiles, concrete remains, and plastic objects. However, about 60% of the records correspond to species dwelling on soft and hard bottoms (Figure 4). Regarding the bathymetrical distribution, individuals have been recorded in depths up to 2,875 m, but most of them in the range between 0 to 15 m (Figure 5).

Figure 3 Relative dominance of species in each ecoregion. TAY: Tayrona ecoregion; MAG: Magdalena ecoregion; SAN: Archipelago of San Andrés and Providencia ecoregion; GUA: Guajira ecoregion; MOR: Golfo de Morrosquillo ecoregion; ARCO: Coral Archipelagos ecoregion; DAR: Darién ecoregion; PAL: Palomino ecoregion; COC: Oceanic Caribbean ecoregion

Discussion

Báez & Ardila (2003) recorded 43 families, 138 genera, and 238 species of polychaetes; our update has increased these figures to 51, 230, and 293, respectively. Even including the number of polychaete species recorded in the country's Pacific coasts (Londoño-Mesa, 2011), the total number would be small compared to the 1,500 species recorded in México alone (Tovar-Hernández, et al., 2014), or the 1,341 species recorded in Brazil (Lana, et al., 2017). This clearly shows the need to increase the number of taxonomic studies in Colombian waters. The estimate of species richness would be more accurate if further taxonomic revisions were carried out. For example, the revision of terebelids polychaetes in Colombia (Londoño-Mesa, 2011) led to a reduction in the number of recorded genera, but the number of species records increased in about 50% (Londoño-Mesa, 2017). Likewise, there are cases of species complexes waiting to be solved such as Neanthes acuminata and N. caudata (Reish, et al., 2014), Lumbriconereis latreilli and L. floridiana (Carrera-Parra 2001), Cirriformia filigera and Timarete filigera (Magalhãe, et al., 2014), which could lead to an increase in the number of species records for Colombia.

Species recorded for the first time in previous checklists lack species diagnoses, information on methods and habitat, and vouchers in biological collections. It is highly recommended that future surveys where new records are registered include such aspects and that specimens be deposited in biological collections so that they will be available when identifications need confirmation. Consequently, this will allow for more accurate estimates of diversity.

Bias in the records is evident. Families with high numbers of species records (e.g. Eunicidae, Syllidae, Nereididae, and Terebelidae) (Figure 2) are the consequence of the particular preference of some authors for those families. Families such as Spionidae and Capitellidae contribute considerably to the number of genera records because they are abundant in soft bottoms where most ecological studies or environmental assessments are performed, however, most of this type of studies rarely provide identification to the species level. Localities with high richness seem to be related to the closeness of the research institutes that have undertaken extensive scientific efforts to catalog their marine vicinities (Miloslavich, et al., 2010). The security and accessibility to the different ecoregions also seem to have some impact on the knowledge of the polychaete diversity. Regarding the bathymetric distribution, most of the records came from depths up to 15 m where the sampling methods are easier and less expensive.

To have more comprehensive and accurate results of the diversity of polychaetes in the Caribbean coast of Colombia we recommend: 1) To focus on families with few species records; 2) to use integrative taxonomy methods to validate taxa; 3) to make a greater sampling effort in the ecoregions with few or no records; 4) to be more rigorous in the taxo-nomic work, which should include complete information on the habitat, bathymetric range, and ecological remarks, and to deposit the biological material examined in a scientific reference collection when new records are published.