Introduction

Trypanosoma rangeli, a non-pathogenic hemoflagellate capable of infecting a variety of mammalian species, including humans, is transmitted via triatomine insects belonging to the genus Rhodnius (Hoare, 1972; Guhl & Vallejo, 2003). The interaction between the parasite and Rhodnius prolixus begins with the ingestion of blood containing trypomastigotes. Following ingestion, the parasites develop into epimastigotes in the intestine of the vector, where they come into contact with the products of blood digestion and other components of the midgut including the bacterial microbiota, hemolytic factors, lectins, the prophenoloxidase system, antimicrobial peptides, and reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (Vieira, et al., 2015). While these factors can act as biochemical barriers to T. rangeli infection, the parasite can still cause immunosuppression in R. prolixus by inhibiting processes such as phagocytosis, microaggregation of hemocytes, prophenoloxidase activation, and eicosanoid synthesis (Figueiredo, et al., 2008; García, et al., 2004a, 2004b). Five T. rangeli genotypes (A-E) have been identified (Maia da Silva, et al., 2007; Vallejo, et al., 2015); however, we do not know whether all genotypes are capable of crossing the intestinal cell wall in R. prolixus, where they multiply in the hemocoel, migrate to the salivary glands, and produce infectious metacyclic trypomastigotes to complete their life cycle.

Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiologic agent of Chagas disease, is transmitted by more than 140 species of triatomines (Galvao & Justi, 2015). Blood trypomastigotes are ingested by the vector in the intestine and then they progress to the amastigote, epimastigote, and spheromastigote developmental stages before they are finally eliminated in the feces as infectious metacyclic trypomastigotes (Vallejo, et al., 1988). All T. cruzi strains, which are classified into six discrete-typing units (DTU) (TcI-TcVI) (Zingales, et al., 2009, 2012), as well as the more recently identified Tcbat (Marcili, et al., 2009) and T. cruzi marinkellei strains (Barker, et al., 1978), remain exclusively within the intestine of the insect vector where they interact with the intestinal microbiota and counteract the effects of host defense factors such as defensins (López, et al., 2003; Vieira, et al., 2016), prolixicins (Ursic-Bedoya, et al., 2011), lysozymes (Buarque, et al., 2013; Ursic-Bedoya, et al., 2008), lectins (Pereira, et al., 1981; Mello, et al., 1996), components of the phenoloxidase cascade (Castro, et al., 2012; De Fuentes-Vicente, et al., 2016), and nitric oxide (Whitten, et al., 2007).

In a previous study, Pulido, et al. identified differential lytic activity against T. rangeli strains in hemolymph from R. prolixus colonies fed on chicken blood and maintained for 10 years in the laboratory (Pulido, et al., 2008). Similarly, Mello, et al. showed differential trypanolytic activity against different T. cruzi strains in hemolymph from a 20-year-old colony of R. prolixus fed on citrated rabbit blood (Mello, et al., 1996). These results indicate that R. prolixus can generate trypanolytic factors in hemolymph without prior exposure to T. rangeli or T. cruzi, which may have some effect on parasite development. While the factors responsible for this lytic activity have yet to be fully characterized, they are likely to be related to a systemic immune response of the vector to other microorganisms of the intestinal microbiota.

To understand the dynamics of parasite transmission, a tripartite approach focusing on triatomine-trypanosome-microbiome interactions has been proposed, which requires the integration of microbiological, genomic, ecological, bioinformatics, biochemical, and biological techniques to explain these interactions and how they may affect the transmission of trypanosomes (Salcedo-Porras & Lowenberger, 2019). To achieve this, it is necessary to use both wild and established triatomine colonies with different microbiota from geographically distinct locations together with Trypanosoma strains with different genotypes and DTUs to study innate immunity and links with the biology of trypanosomes that could be exploited to reduce parasite transmission (Salcedo-Porras & Lowenberger, 2019).

Our search of current literature revealed little information on the presence of innate trypanolytic factors in the hemolymph of triatomines other than R. prolixus. Therefore, we aimed to examine laboratory populations of five Rhodnius species, Triatoma dimidiata, T. maculata, and Panstrongylus geniculatus, as well as wild populations of R. pallescens and T. dimidiata, for the presence of innate trypanolytic factors against a range of T. rangeli and T. cruzi strains belonging to different genotypes and discrete taxonomic units (DTUs). Additionally, we studied whether the trypanolytic activity was related to the sex and stage of the insect, the time parasites are kept in culture and the time of the colonies in the laboratory. This is the first comparative study on the innate trypanolytic activity of hemolymph among different triatomine species. The results of this study provide a basis for further studies aimed at characterizing the intestinal microbiota of triatomines, which may impact the innate immunity of the vector species, and at identifying the factors responsible for the lytic activity of the hemolymph against T. rangeli and T. cruzi and their possible role in the transmission of parasites.

Materials and methods

Trypanosoma rangeli and Trypanosoma cruzi strains

Trypanosoma rangeli strains belonging to genotypes B, D, and E and T. cruzi strains belonging to reference DTUs TcII-TcVI were provided by Dr. Martha G. Teixeira from the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at the University of São Paulo. These strains were removed from liquid nitrogen storage and thawed. Once they arrived at the Tropical Parasitology Research Laboratory (LIPT) at the University of Tolima, they were refrozen in liquid nitrogen. Aliquots were thawed and cultured as needed. The T. rangeli genotype A strain (Choachí) was maintained by mouse-culture-R. prolixus cyclic passes every 3 months, while the genotype C strain (R. col 0226) was maintained by mouse-culture-Rhodnius colombiensis cyclic passes every 3 months (Vallejo, et al., 1986). Clones of both domestic and sylvatic TcI, as well as Tcbat and T. cruzi marinkellei strains isolated from bats in Colombia and maintained in liquid nitrogen, were also used in this study. Additionally, TcI (MHOM/CO/03/CG) and TcII (Y) strains were maintained in ICR mice. T. cruzi DTUs and T. rangeli genotypes were confirmed using previously described molecular markers (Souto & Zingales, 1993; Souto, et al., 1996; Brisse, et al., 2001; Villa, et al., 2013; Vallejo, et al., 2002; Maia da Silva, 2007). For assays involving T. cruzi, we used 36 representative strains belonging to DTUs TcI-TcVI and Tcbat, one domestic T. cruzi TcI clone, and one sylvatic T. cruzi TcI clone. For the assays involving T. rangeli, we used 23 strains representing genotypes A-E along with one Trypanosoma leeuwenhoeki strain (Table 1). T. cruzi strains were cultured at 28°C in biphasic Novy-McNeal-Nicolle/liver infusion tryptose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum while T. rangeli strains were cultured in biphasic Bacto™ beef medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Table 1 Strains of T. rangeli genotypes and T. cruzi DTUs used in this study

| T. rangeli genotype or T. | Strain | Host | Geographical origin | Lysis caused by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cruzi DTU | R. prolixus hemolymph | |||

| T. rangeli A | Duran | Homo sapiens | Cundinamarca (Colombia) | - |

| T. rangeli A | Choachi | R. prolixus (domestic) | Cundinamarca (Colombia) | - |

| T. rangeli A | TrD P19 | R. prolixus (domestic) | Norte Santander (Colombia) | - |

| T. rangeli A | TrP 500 | R. prolixus (sylvatic) | Casanare (Colombia) | - |

| T. rangeli B | Saimiri | Saimiri sciureus | Manaus (Brazil) | - |

| T. rangeli C* | Ort Q 09-1 | Artibeus lituratus | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. rangeli C | Ort Q 09-2 | A. lituratus | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. rangeli C | R. col 089 | R. colombiensis | Coyaima (Colombia) | + |

| T. rangeli C | R. col 0201 | R. colombiensis | Coyaima (Colombia) | + |

| T. rangeli D | SC-58 | Echimys dasythrix | Santa Catarina (Brazil) | - |

| T. rangeli E | 643 | Platyrrinus lineatus | Miranda (Brazil) | + |

| T. leeuwenhoeki | Tas 250 | Bradypus variegatus | Pacific Region (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi I ** | Ort 1-5 | R. colombiensis | Ortega (Colombia) | - |

| T. cruzi I | Dm28 | Didelphis marsupialis | Coyaima (Colombia) | - |

| T. cruzi I | 833 | H. sapiens | Pará (Brazil) | - |

| T. cruzi I | D1 | D. marsupialis | Coyaima (Colombia) | - |

| T.cruzi I domestic clone | MHOM/CO/03/CG | H. sapiens | Caquetá (Colombia) | - |

| T. cruzi Id sylvatic clone | Rcol/02 | R. colombiensis | Coyaima (Colombia) | - |

| T. cruzi II | Y | H. sapiens | Sao Paulo (Brazil) | + |

| T. cruzi II | 139 | D. aurita | Sao Paulo (Brazil) | + |

| T. cruzi III | MT 3663 | P. geniculatus | Amazonas (Brazil) | - |

| T. cruzi IV | José Julio | H. sapiens | Amazonas (Brazil) | - |

| T. cruzi V | 967 | H. sapiens | Bolivia | + |

| T. cruzi VI | CL Brener | T. infestans | Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Ortq07-1 | Artibeus lituratus | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Ortq07-2 | A. lituratus | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Ortq07-3 | A. lituratus | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Ortq08-1 | Carollia perspicilata | Ortega (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Cha Q 11-2 | A. lituratus | Chaparral (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi bat | Cha Q 12-1 | C. perspicilata | Chaparral (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi marinkellei | Cha Q 08-1 | Phyllostomus hastatus | Chaparral (Colombia) | + |

| T. cruzi marinkellei | Cha Q 08-2 | P. hastatus | Chaparral (Colombia) | + |

* In addition to the four strains of T. rangeli C described, 13 strains of the same genotype that presented lysis caused by the hemolymph of R. prolixus were also tested.

** In addition to the six strains of T. cruzi I described in the table, 14 strains of this DTU that also presented resistance to lysis caused by the hemolymph of R. prolixus were tested.

+: Presence of lysis

Triatomines

In this study, we used fifth-instar nymphs and adults belonging to Colombian triatomine species R. colombiensis, R. pallescens, R. pictipes, R. prolixus (domestic), R. prolixus (sylvatic), R. robustus, T. dimidiata, T. maculata, and P. geniculatus, which were maintained in an insectary. The insects were fed weekly on chickens and housed in incubators with a 12-h light/12-h dark photoperiod at 28°C and 80% relative humidity. Fifth-instar nymphs and adults belonging to the species R. colombiensis and T. dimidiata were also collected from sylvatic environments and used to obtain hemolymph for the analysis of their trypanolytic activity.

Detection of trypanolytic activity against T. rangeli and T. cruzi in the hemolymph of triatomines

Insects were fed on chickens 8 days before the assays. Hemolymph was collected by making a cut in the femur of the third hind leg and applying very slight abdominal pressure. Hemolymph samples from 20 individuals of each species were pooled and then centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 5 min. The resulting cell-free supernatant was used in trypanolytic activity assays performed as described previously by Pulido, et al. (2008). Briefly, to prevent melanization, 2 of 50 mM of phenylthiourea were added to each 100-μl volume of hemolymph. Cultures of T. cruzi or T. rangeli were washed three times with 0.9% (w/v) saline solution, centrifuged at 7000 x g for 5 min, and then resuspended in 10% (v/v) liver infusion tryptose medium. Ten microliters of hemolymph were then added to 10-^l aliquots of parasite suspension at a final concentration of 2.5 x 107 parasites/ml. To assess the lytic activity, live parasites were counted in a Neubauer chamber after 0 and 14 h of incubation. A negative control consisting of hemolymph inactivated with 10 of pepsin solution (15 mg/ml in 1M HCl) per 100 of hemolymph and incubated at 37°C for 4 h was included in all experiments. T. rangeli genotype C (Rcol 0226) and T. cruzi TcII (Y) strains were used as positive controls with both strains always lysed when incubated with hemolymph from R. prolixus. T. rangeli genotype A (Choachí) and T. cruzi TcI (Dm28) strains were used as negative control strains, which were not lysed when incubated with hemolymph from R. prolixus. For both the negative and positive controls, the parasites were resuspended at a final concentration of 2.5 x 107 parasites/ml. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

An underlying question of this study was whether keeping the triatomine colonies in the laboratory could affect the innate lytic factors, whereby lytic activity could be lost after several generations. To address this question, we collected R. colombiensis and T. dimidiata specimens from the field and used pooled hemolymph from each species in trypanolytic activity assays with the T. cruzi TcII (Y) strain. All controls described above were included in these assays. The results were compared with those obtained using colonies of the same species that had been maintained in the laboratory for 5 and 20 years.

We also investigated whether the long-term maintenance of cultured epimastigotes could affect their resistance to lysis. In these assays, R. prolixus hemolymph was incubated with T. cruzi TcII strain Y obtained from recent hemoculture of mouse blood or with T. cruzi TcII strain Y that had been kept in culture with weekly subcultures for 4 years. We also compared the lytic activity of hemolymph from vectors fed with chicken blood or mouse blood, and from R. prolixus nymphs, males, and females.

Ethical aspects

The project was approved by the Central Research and Scientific Development Committee at the University of Tolima after verifying that the proposed protocols were in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in Resolution 8430 of 1993 by the Colombian Ministry of Health for the handling of laboratory animals. The technicians in care of the animals at the LIPT observed all aspects related to their maintenance following strict regulations for ensuring the animals' consistent care and handling.

Statistical analysis

Parasite counts at 0 and 14 h of incubation are presented as means ± standard deviation. For strains showing lysis at 14 h, the percentage of lysed cells was calculated by comparing with the number of parasites at 0 h. T. rangeli and T. cruzi strains that were not lysed at 14 h were observed for 10 h more (24 h of incubation). We conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc analysis to identify significant differences among the strains. The differences between the treatments and the controls were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Graphs were generated using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Effects of R. prolixus hemolymph on T. rangeli strains belonging to different genotypes

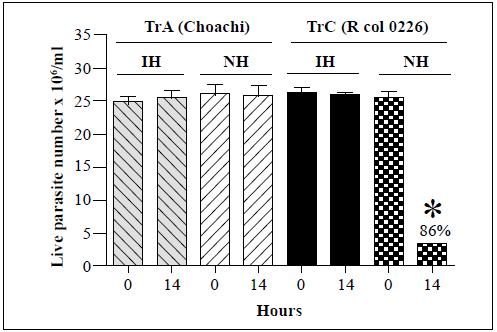

The effects of R. prolixus hemolymph on the survival of T. rangeli genotype A (Choachi) and genotype C (Rcol0226) strains are shown in figure 1. The T. rangeli genotype C strain showed an 86% decrease in live parasite numbers at the 14-h time point compared to those at time point 0 in the presence of native hemolymph but was not affected by incubation with the inactivated hemolymph. Instead, no changes in the live parasite counts of the T. rangeli genotype A strain were observed following incubation with either the inactivated or native hemolymph suggesting that it was not susceptible to the lytic effects of the hemolymph. Therefore, these two strains were used as the positive (presence of lysis) and negative (absence of lysis) controls, respectively, for all subsequent analyses of genotype B, D, and E T. rangeli strains.

Each bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasite counts from three independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation. Each T. rangeli strain was incubated with inactivated hemolymph (IH) or native hemolymph (NH). *: p<0.05 compared with the live parasite counts of genotypes A and C strains incubated with NH at the same time point.

Figure 1 In vitro survival of T. rangeli genotype A (Choachi) and C (Rcol0226) strains following incubation with hemolymph from R. prolixus

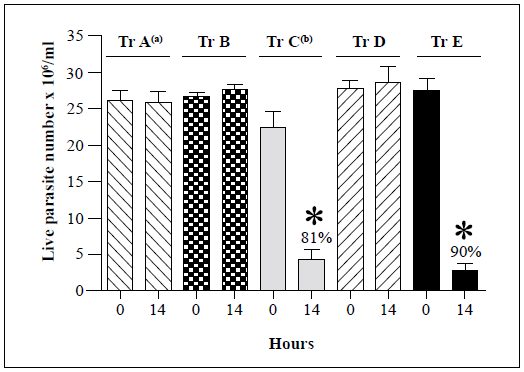

Representative strains belonging to each of the remaining T. rangeli genotypes (B, D, and E) were then assessed for their susceptibility to the lytic activity of the R. prolixus hemolymph (Figure 2). No significant changes in the live parasite counts of genotype A, B, and D strains were observed after 14 h of incubation with either the inactivated or native hemolymph while 81% and 90% decreases in live parasite counts were observed for genotype C and E strains, respectively, following incubation with native hemolymph. The genotype A, B, and D strains remained resistant to lysis after 24 h of incubation (Table 2).

Each bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasite counts from three independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation with native hemolymph. T. rangeli genotypes A (Choachi), B (Saimirí), C (Rcol0226), D (SC58), and E (643) strains were examined. a: Lysis resistance was observed in four genotype A T. rangeli strains. b: Lysis susceptibility was observed in 17 genotype C T. rangeli strains. Only one strain was tested for each of B, D, and E genotypes (Table 1). The Rcol0226 and Choachi strains were used as the positive (presence of lysis) and negative (absence of lysis) controls, respectively, for analyses of genotypes B, D, and E strains. *: p<0.05 compared with the live parasite counts of the negative control with the native hemolymph NH at the same time point.

Figure 2 Summary of in vitro survival of genotypes A-E of T. rangeli strains following incubation with native hemolymph from R. prolixus

Effects of R. prolixus hemolymph on T. cruzi strains belonging to different DTUs

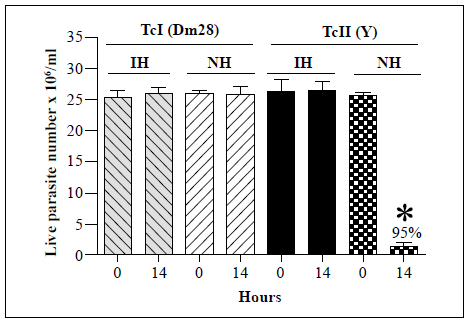

The effects of R. prolixus hemolymph on the survival of T. cruzi Tel (Dm28) and TcII (Y) strains were then examined (Figure 3). No significant changes in the live parasite counts of the T. cruzi Tel strain were observed following incubation with either the inactivated or native hemolymph. In contrast, there was a 95% decrease in live parasite numbers of the T. cruzi TcII strain (Y) after 14 h of incubation with the native hemolymph compared with the counts at time point 0. As a result, T. cruzi Tel strain Dm28 and TcII strain Y were used as negative and positive controls, respectively, for all further assays.

Each bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasite counts from three independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation with hemolymph. Each T. cruzi strain was incubated with inactivated hemolymph (IH) or native hemolymph (NH). *: p<0.05 compared with the live parasite counts of the T. cruzi Tel and the TcII strains incubated with NH at the same time point

Figure 3 In vitro survival of T. cruzi Tel (Dm28) and TcII (Y) strains following incubation with hemolymph from R. prolixus

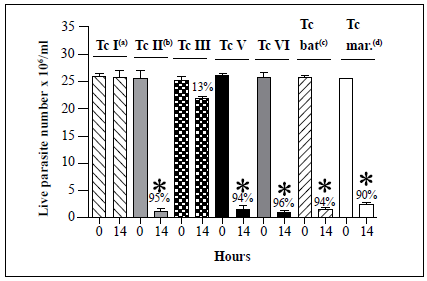

We examined then the susceptibility of the remaining T. cruzi strains (TcIII, TcV, TcVI, Tcbat, and Tcmarinkellei) to lysis by the hemolymph (Figure 4). Analysis of 20 Tel strains showed complete resistance to lysis in all cases. The TcIII strain showed only partial susceptibility to lysis with a 13% decrease in live parasite counts observed after 14 h of incubation with the native hemolymph compared with parasite counts at time point 0. In contrast, decreases in live parasite counts of 95%, 94%, 96%, 94%, and 90% were observed for the TcII, TcV, TcVI, Tcbat, and T. cruzi marinkellei strains, respectively, after 14 h of incubation with the native hemolymph. Interestingly, analysis of a TcIV strain (Jose Julio) revealed a high degree of agglutination but no evidence of lysis after 24 h of incubation with the native hemolymph (Table 2).

Each T. cruzi marinkellei bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasites counts from three independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation with hemolymph. Tel (Dm28), TcII (Y), TcIII (MT3663), TcV (967), TcVI (CL Brener), Tcbat (Ort07-1), and T. cruzi marinkellei (ChaQ 08-1) strains were examined in this assay. s, Lysis resistance was observed in 20 Tel strains. b, Lysis susceptibility was observed in two TcII strains. c, Lysis susceptibility was observed in six Tcbat strains. d, Lysis susceptibility was observed in two T. cruzi marinkellei strains. Only one strain was examined for each of the TcIII, TcV, and TcVI DTUs (Table 1). T. cruzi Tel strain Dm28 and TcII strain Y were used as negative (absence of lysis) and positive (presence of lysis) controls, respectively, for assays with TcIII, TcV, TcVI, Tcbat, and T. cruzi marinkellei strains. *, p < 0.05 compared with the live parasite counts of the negative controls with the native hemolymph (NH) at the same time point.

Figure 4 Summary of in vitro survival of T. cruzi strains belonging to six different DTUs, as well as one T. cruzi subspecies (T. cruzi marinkellei), following incubation with native hemolymph from R. prolixus.

Table 2 summarises the results of the hemolymph lytic activity in eight triatomine species after 24 hours of incubation with representative strains from five T. rangeli genotypes, seven T. cruzi DTUs, and a T. cruzi subspecies. The T. rangeli C and E genotype strains and the DTU TcII, TcIII, TcV, TcVI, Tcbat, and the Tcmarinkellei strains were lysed by R. prolixus and R. robustus hemolymphs. T. rangeli genotype A and B strains and Tel strain were not lysed. The TcIV strain became agglutinated but not lysed. It is worth noting that none of the R. colombiensis, R. pallescens, R. pictipes, T. dimidiata, T. maculate, and P. geniculatus hemolymphs had lytic activity against T. rangeli and T. cruzi strains incubated in the same experimental conditions used here indicating the absence of trypanolytic activity in their hemolymphs during the first 24 hours of incubation.

Comparison of hemolymph from triatomines from wild and laboratory colonies

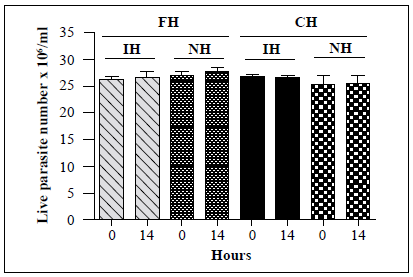

Next, we examined whether the maintenance of insects in laboratory colonies had any effect on the lytic activity of hemolymph. Hemolymph was obtained from 37 R. colombiensis specimens captured from palm trees in Coyaima, Colombia, in September 2018. Hemolymph was also extracted from i?, colombiensis individuals from a colony that has been maintained in the laboratory for 5 years. Assays were conducted using T. cruzi TcII strain Y, which is susceptible to lysis. No significant differences in live parasite counts were observed for any of the treatments (Figure 5). Identical results (absence of lysis) were observed when the assay was repeated using hemolymph from a laboratory colony of T. dimidiata and specimens captured in sylvatic environments in Boyacá, Colombia, in May 2019 (data not shown).

Figure 5 In vitro survival of a T. cruzi TcII strain following incubation with hemolymph from laboratory and field-collected i?, colombiensis insects and comparison of the number of live T. cruzi TcII (Y) epimastigotes following incubation with the hemolymph from R. colombiensis specimens captured in the field (FH) and hemolymph from R. colombiensis individuals from a colony maintained in the laboratory for 5 years (CH). Each bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasite counts from two independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation with hemolymph. The T. cruzi parasites were incubated with inactivated hemolymph (IH) or native hemolymph (NH) from both populations.

Effects ofparasite culture time on susceptibility to the lytic activity of native hemolymph from R. prolixus

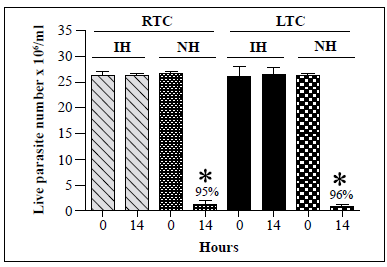

We then compared the susceptibility of recently obtained and long-term cultures of T. cruzi TcII strain Y to lysis by R. prolixus hemolymph. The first TcII strain Y isolate was obtained from recent hémoculture of mouse blood while the second isolate had been maintained in a 4-year culture with weekly subcultures. As shown in Figure 6, the lytic activity of the hemolymph against the two cultures was similar with 95% and 96% decreases in T. cruzi live parasite counts following incubation of native hemolymph with recently obtained and long-term cultures, respectively. Besides, no lysis of T. rangeli A strain Choachi maintained either via a cyclic culture-R. prolixus -mouse-culture method, which allowed us to obtain recent cultures of the parasite, or by weekly subculture for 3 years, was observed following incubation with native hemolymph from R. prolixus (data not shown). On the other hand, lysis of T. rangeli C strain Rcol0226 maintained via a cyclic culture-R, colombiensis -mouse-culture method or by weekly subculture for 3 years was observed following incubation with R. prolixus native hemolymph (data not shown).

*: p<0.05 compared with live parasite counts of IH and NH cultures at the same time point

Figure 6 In vitro survival of T. cruzi TcII epimastigotes from recent or long-term cultures following incubation with native hemolymph from R. prolixus. T. cruzi TcII strain Y isolates recently cultured (recent-term cultivation, RTC) from trypomastigotes from mouse blood or cultured for 4 years (long-term cultivation, LTC) were incubated with native hemolymph from R. prolixus. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of live parasite counts from three independent assays after 0 and 14 h of incubation with hemolymph. The same number of T. cruzi epimastigotes from the RTC and LTC cultures were incubated with inactivated hemolymph (IH) and native hemolymph (NH).

In addition to the results presented here, we also determined that the lytic activity was similar in hemolymph from vectors fed on chicken or mouse blood and in hemolymph from R. prolixus nymphs, males, and females.

Discussion

The results of the study support previous reports on the existence of a rapid innate response to various T. rangeli genotypes and T. cruzi DTUs in the hemolymph of R. prolixus.Sánchez, et al. (2005) and Pulido, et al. (2008) showed that the epimastigotes of T. rangeli genotype C strains isolated from R. colombiensis, R. ecuadoriensis, and R. pallescens were lysed when incubated in vitro for 10 h with hemolymph from R. prolixus. In contrast, the epimastigotes of a T. rangeli genotype A strain were completely resistant to lysis under the same conditions. In the present work, T. rangeli genotype A, B, and D strains were resistant to lysis during incubation with hemolymph from R. prolixus for 24 h while 81% and 90% decreases in live parasite counts were observed for genotype C and E strains after 14 h of incubation with the hemolymph (Figure 2, Table 2).

In vivo assays where the hemocoel of R. prolixus was inoculated with T. rangeli genotype C strains showed the rapid disappearance of the flagellated parasite from the hemolymph of the vector (data not shown). This is consistent with the results of Sánchez, et al. (2005) regarding the complete clearance of T. rangeli genotype C cells from the hemolymph at 2 h post-inoculation. In contrast, inoculated T. rangeli genotype A cells were observed in the hemolymph of T. rangeli for several months with the production of infective metacyclic trypomastigotes (Vallejo, et al., 1986). As a result, this inoculation method is commonly used to obtain infective trypomastigotes of T. rangeli genotype A strains. Similar findings had already been reported by Mello, et al. (1995), who inoculated T. rangeli strain San Agustín (genotype A from Colombia) into the hemocoel of R. prolixus. The researchers observed the multiplication of the parasite in the hemolymph for several days with elevated levels of lysozyme activity in the hemolymph but no trypanolytic or antimicrobial peptide activity.

Under experimental conditions, T. rangeli genotype A strains are not lysed following inoculation into the R. prolixus hemocoel while genotype C strains are lysed. This innate lytic response would explain why after characterizing more than 100 T. rangeli strains isolated from the salivary glands of R. prolixus from Colombia, Honduras, and Venezuela (Salazar-Anton, et al., 2009), wild Rhodnius neglectus from the Federal District of Brazil (Gurguel-Goncalves, et al., 2004; Urrea, et al., 2005), wild R. prolixus from Casanare, Colombia (Urrea, et al., 2011), and R. robustus from Venezuela and Brazil were found to be genotype A (Maia da Silva, et al., 2007; Vallejo, et al., 2015). In these studies, none of the R. prolixus, R. robustus or R. neglectus vectors were infected with genotype C or E strains, which are susceptible to hemolymph lysis.

Trypanosoma rangeli genotype C strains have been isolated from wild R. pallescens colonies from Panamá and Colombia, from wild R. colombiensis colonies from central Colombia, and from domesticated R. ecuadoriensis in the northern region of Perú (Urrea, et al., 2005; Vallejo, et al., 2015). No trypanolytic activity was detected in the hemolymph of these vectors and no lysis was observed following experimental inoculation of a T. rangeli genotype A strain into the hemocoel of R. colombiensis and R. pallescens, although the parasites did not invade the salivary glands (data not shown).

The absence of lytic activity in the hemolymph of Triatoma and Panstrongylus species (T. dimidata, T. maculata, and P. geniculatus) in the current study (Table 2) coincides with the observations of De Stefani-Marques, et al. (2006), who orally infected P. megistus, T. infestans, T. sordida, T. braziliensis, and T. vitticeps individuals with a strain of T. rangeli isolated in Uberaba-Minas Gerais, Brazil, where genotype A predominates. The authors observed the parasites in the hemolymph for 10-30 days following infection without invasion of salivary glands, thus confirming the absence of lytic factors with immediate activity in these vectors.

The inability of T. cruzi to develop in the hemolymph of triatomine vectors was observed in in vivo experiments performed by Alvarenga & Bronfen (1982), who inoculated T. cruzi strains Y and CL into the hemocoel of T. infestans and Dipetalogaster maxima. They observed that the parasites could not persist in the hemolymph for more than 40 days. In comparison, Mello, et al. (1995) inoculated T. cruzi clone Dm28 into the hemocoel of R. prolixus and found that the parasites were completely cleared by day 5 post-inoculation suggesting that the humoral response in hemolymph from R prolixus against T. cruzi is faster than that in hemolymph from T. infestans and D. maxima. Early and strong lytic activity was previously observed by Mello, et al. (1996) in in vitro experiments with various T. cruzi strains. The authors observed trypanolytic activity in the hemolymph of R. prolixus against T. cruzi strain Y but not against strains Dm28c or CL after 3 h of incubation. Thus, T. cruzi clearance depends on both the parasite strain and the vector species. However, the exact mechanism that causes T. cruzi to die in the hemocoel but thrive in the gastrointestinal tract remains unknown (Salcedo-Porras & Lowenberger, 2019).

Although under natural conditions T. cruzi does not enter the hemolymph of the vectors, we decided to use epimastigotes of T. cruzi belonging to various DTUs to detect the presence of trypanolytic factors related to an innate immune response in the vectors. Differences in susceptibility to lysis were observed amongst the T. cruzi strains belonging to different DTUs, with a TcIII strain showing a 13% decrease in live parasite numbers after 14 h of incubation, while a Tcl strain remained unaffected after 24 h of incubation. We observed strong in vitro lytic activity during incubation of T. cruzi with hemolymph from R. prolixus, with 90%-96% decreases in live parasite counts recorded in the first 14 h of incubation (Figure 4). We could not determine the cause of this variability; however, susceptibility or resistance to lysis of T. cruzi strains belonging to different DTUs and T. rangeli strains belonging to different genotypes may be related to the ability of the different strains to survive the oxidative stress of the hemolymph. It is likely that the parasites that showed resistance to lysis maintain a repertoire of genes involved in oxidative stress tolerance, which would aid in survival under environmental stress conditions. The variability of the antioxidant defenses of the various T. cruzi and T. rangeli strains may reflect specific adaptations to the vector species (Stoco, et al., 2014; Beltrame-Botelho, et al., 2016). However, the most intriguing result of the present study was that none of the other vector species, including R. pallescens, R. colombiensis, R. pictipes, T. dimidiata, T. maculata, and P. geniculatus, showed hemolymph lytic activity against any of the T. cruzi or T. rangeli strains after 24 h of incubation (Table 2).

The lytic activity of hemolymph from field-collected insects and laboratory colonies of R. colombiensis (Figure 5) and of T. dimidiata against TcII was not observed in any of the hemolymph samples indicating that the absence of lytic activity is independent of the maintenance of colonies in the laboratory. Similarly, lytic activity tests against TcII using R. prolixus colonies from six different departments in Colombia (Boyacá, Casanare, Cundinamarca, Magdalena, Santander, and Tolima) showed equivalent levels of lytic activity in hemolymph from all colonies.

We also found that there was no difference in the lytic susceptibility of T. cruzi TcII epimastigotes recently obtained by blood culture and those maintained in culture for 4 years with weekly subcultures (Figure 6), which indicates that the maintenance time of epimastigotes in culture does not affect their susceptibility to lysis caused by the native hemolymph from R. prolixus. There were no differences either in the trypanolytic activity of hemolymph from R. prolixus adults (males and females) and fifth-instar nymphs or in hemolymph from insects fed on chicken or mouse blood.

A question that is yet to be resolved is whether these innate trypanolytic factors detected in the hemolymph could also be activated in the intestine to modulate the transmission of intestinal T. cruzi parasites. More studies are needed to address this hypothesis, identify innate trypanolytic factors, locate production sites, and determine circulation dynamics and their effector activities in different vector organs and tissues.

Regarding the possible mechanisms related to hemolymph lytic activity, it is known that prophenoloxidase system (PPO) activation leads to melanin synthesis by indolquinone polymerization. Both melanin and the intermediary products formed during its synthesis help kill bacteria, viruses, and parasites (Walters & Ratcliffe, 1983; Söderhäll & Cerenius, 1998; Cerenius, et al., 2008, Azambuja, et al., 2017). PPO availability in the hemolymph of the insects is derived from hemocyte lysis (Kanost and Gorman, 2008). Hemocyte lysis mainly occurs after exposure to microorganisms (Brehélin, et al., 1989), but may also occur spontaneously to maintain basal prophenoloxidase (PPO) levels in hemolymph (Kanost & Gorman, 2008). Hemolymphs from the eight triatomine species were used in all the parasite incubation experiments in our study; they were hemocyte-free and treated with phenylthiourea, which would have prevented basal PPO levels activation. In principle, the lytic activity observed in R. prolixus and R. robustus hemolymph should not have been attributed to PPO activation but related to factors other than the PPO cascade.

In a previous study, it was found that R. prolixus hemolymph lytic factors or their precursors were proteins (Pulido, et al., 2008); here, we confirmed this finding because hemolymph lytic activity disappeared completely after pepsin incubation. It can be predicted, then, that potential lytic factors or their precursors are proteins and could be antimicrobial peptides (AMP), precursors of reactive nitrogen species (NOS) or reactive oxygen species (ROS) or nitrophorins that are NOS transporters or proteins not yet identified. Proteomic and transcriptomic studies comparing vector species having or lacking lytic activity should be carried out to identify possible candidates and subsequent tests performed to confirm their role in hemolymph lytic activity.

The strategies used by T. rangeli and T. cruzi to achieve successful vector infection depend on a tripartite interaction among the parasite, the insect's immune system, and the intestinal microbiota. Experimental infection studies using different bacterial species have shown species-specific differences in the intestinal immune response of the vectors (Vieira, et al., 2014). These interactions constitute an important field of research that will open new perspectives on our understanding of parasite-vector relationships. As part of this tripartite interaction, it will be very important to characterize the microbiomes of insect populations that have a very strong innate humoral response, such as that detected in R. prolixus and R. robustus. Investigations of this tripartite interaction could lead to the identification of intestinal microbial species that naturally induce an immune response in the intestine or hemolymph of the vector to avoid parasite infection. Further research is needed to identify the components of the strong differential immune response between insects having and lacking lytic activity to verify whether such factors could be involved in T. rangeli genotypes and T. cruzi DTUs' predominance in Colombia and some Latin American regions.

Conclusions

Using in vitro incubations of T. rangeli and T. cruzi epimastigotes from different genotypes and DTUs with the hemolymph of eight species of triatomines, we detected strong trypanolytic activity in the hemolymph from R. prolixus and R. robustus, which was absent in that from R. colombiensis, R. pallescens, R. pictipes, T. dimidiata, T. maculata, and P. geniculatus. The trypanolytic activity was independent of the sex and stage of the insect, the time the epimastigotes were maintenance in culture, and the type of food on which the vectors were fed (chicken or mouse blood). The absence of trypanolytic activity was observed in both laboratory colonies and field-captured insects of the species R. colombiensis and T. dimidiata. There are still gaps in our understanding of the innate immune responses of different triatomine species against the same strains of T. cruzi and T. rangeli or the same triatomine species against geographically-separated isolates of T. cruzi and T. rangeli. Interactions between triatomines and trypanosomes involve complex ecological, biochemical, and coevolutionary relationships that are just beginning to be investigated. Understanding the factors that determine how a vector is infected and how the parasite is transmitted is key to the success of control programs targeting Chagas disease vectors; unfortunately, most of these factors are unknown. Therefore, it is vital to investigate the ecological, physiological, and immunological factors that determine how and why the vectors transmit some genotypes of the parasite and others do not.