Introduction

Learning English as a foreign language (EFL) in Colombia has become a priority for the Colombian government in the last decades. Programs like “Colombia Bilingüe” and “Bogotá Bilingüe” (Bilingual Colombia and Bilingual Bogota) have been launched to improve the proficiency level of students (Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá, 2005; Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2005). Accordingly, students entering higher education in Colombia must complete a B1 level of proficiency in accordance with the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001) as a requirement for graduation.

At Universidad Nacional de Colombia, students need to achieve this level focused on the reading comprehension of academic texts (Consejo Superior Universitario, 2008), and fulfilling this requirement is the main reason why students access the formal study of English when they reach the university level. Two thirds of the population moving into higher education were found to have an A1 Basic User English proficiency level by 2012 (British Council, 2015; ICFES, 2016).

The Student Welfare Division at Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogota encourages the creation of spaces to enhance the academic, interpersonal, and artistic skills of its students, who mostly belonged to the lowest three socioeconomic strata of the city, at the time of the study (Oficina Nacional de Planeación de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2014). Students have access to EFL classes and specialized materials in universities (Council of Europe, 2001); nonetheless, there are not many authentic grade free settings for the practice of the language. It is in this context that The E Theater was conceived. This paper presents the effects on the L2 skills and competences of the participants in The E Theater: an EFL theater group at Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

The project was created in March of 2008 by a group of students majoring in English Philology and Language. It aims to promote the learning of the English language through a literary and cultural approach by means of performing primarily literary pieces from English speaking authors. The E Theater is supported by the Project Management Unit, a section of the Welfare Division of the University that grants funds for the development of students’ initiatives, projects, and research conducting to students’ well-being. Every semester the approval by the University is renewed, and every year or semester a new piece is chosen and staged. The group combines the advisory on theater provided by its director with the linguistic and pedagogical expertise of the language professionals that are in the head of its coordination and that guide the group’s L2 development (Castillo & Gualdron, 2008). It is also the oldest theater for L2 learning group in the city, as documented by Suárez (2012).

Theoretical Framework

Theater and language learning share some of their foundational constructs. Through the findings presented in this study, we expect to tie the experiences lived by the participants of The E Theater’s workshops and methodology to the major existing literature constructs that support the idea of theater as a holistic strategy to teach and learn L2. Likewise, since the group’s methodology has been open and experimental, emergent categories of analysis are expected to appear. Major second language acquisition and theater constructs are explored henceforth.

Ties Between Theater and L2 Learning

Diverse connections between the disciplines of theater and language learning have been described. Theater is a highly experiential art, not only for the audience, but also for the actors intervening and interacting during the set-up of the play. Hence, theater is a constructivist art in nature (Barris, 2013). Acting training is appropriate to provide learners with the simulation of real, authentic, and meaningful language interaction environments necessary for the acquisition of L2 (Herrera & Murry, 2016; Long, 1981). Both theater and L2 learning share communication elements and aim for effective communication (Busà, 2015; Gross, 1977; Ryan-Scheutz & Colangelo, 2004). In addition, L2 and theater get processed similarly in cognition, and theatrical audiovisual elements assist the audience when making sense of a theatrical piece (Dancygier, 2016; Fennessey, 2006; Morrison & Chilcoat, 1998; Radulescu, 2011; Sofia, Spadacenta, Falletti, & Mirabella, 2016).

In the same fashion, L2 and theater teaching and learning are said to involve different kinds of intelligences (Bernal, 2007; Gardner, 1983). Both practices enhance cultural understanding (Essif, 2011; Sobral, 2011) and facilitate cooperative and collaborative learning too (Perone, 2011). Drama has been used as a tool to empower individuals (Leisse, 2008; Skeiker, 2015), and it has been previously found to motivate learners to study a foreign language (Tindall, 2012). Moreover, theater has been shown to incorporate productive and receptive language skills (Gill, 2013; Morrison & Chilcoat, 1998).

Most previous research based on the subject has focused on theater as a way to improve the reading fluency and comprehension of texts (Casey & Chamberlain, 2006; Chou, 2013; Clark, Morrison, & Wilcox, 2009; Lin, 2015; Peregoy, Boyle, & Cadiero-Kaplan, 2008; Ratliff, 2000; Tindall, 2012). Diverse theater techniques like improvisation have been applied for the practice and development of L2 skills (Dinapoli & Algarra, 2001; Kurtz, 2011; Perone, 2011). On this subject, this study results interesting for addressing a longer application of the theater methodology, as well as an exploration of the benefits, other than linguistic, that this practice facilitates.

Second Language Acquisition Constructs Through Theater

Motivation

Motivation influences the execution of conducts that produce learning (Logan, 1976). It is related to aspects such as personality, attitudes, beliefs, and personal needs, which make participants feel attracted to performing certain activities, roles, and tasks (Wright, 1987). Acting training and performance in L2 in a theatrical ensemble offer their participants the 4 Cs of intrinsic motivation: challenge, curiosity, control, and context (Lepper & Henderlong, 2000). Effective foreign language teaching and learning contemplates the phenomenon of intrinsic motivation as the will that comes from the wishes and needs of the individual to carry out a learning task (Brown, 1994). L2 learning through acting allows meaningful, motivational, and inspirational learning (Lin, 2015; Suárez, 2012; Tindall, 2012).

Language Hypotheses

Krashen (1982) presented five key determining hypotheses in second language acquisition; two of the most important are “the input hypothesis” and “the affective filter hypothesis.” The author proposed a causative relationship for acquisition to take place where there are two key factors, an input just a little more complex than what the learner is able to understand and a low affective filter. For Radulescu (2011), theater allows non-native speakers to be part of a non-threatening environment. It lets students have a voice when there is not an autocratic director that imposes his or her viewpoint. In The E Theater, the role of the director is the one of a facilitator and guide of the process.

Constructivism

According to Herrera and Murry (2016), language learners acquire the L2 more quickly when they are immersed in a communicative language learning environment. They learn more effectively when they can extract meaning from context and communication, and have a linguistic and social interaction focused on learning (Herrera & Murry, 2016). Social constructivism places its focus on the social interactions with others (Piaget, 1974). According to Pritchard (2013), it gives a great importance to language since it is the vehicle upon which knowledge is built. Suárez (2012) stated that applications like The E Theater involve active learning and Vygotsky’s (1962) zone of proximal development due to the heterogeneous nature of theater. Acting as a discipline not only implies an introspective study done by the actors and actresses where they build a character from the inside nourished by their own experiences (Stanislavski, 1949/2013), but also it is the interactive art par excellence, in which there is a tangible social and environmental exchange in verbal and non-verbal communication both with the audience and amongst actors during the setting-up process of a play. Theater can constitute a platform for real situation simulations for second language acquisition, and theater training in L2 represents an engaging social and building community interaction where L2 acquisition can take place (Chesler & Chesler, 2005; Ortuzar, 2014; Shosh & Wescoe, 2007).

Authentic Environment

Dinapoli and Algarra (2001) proposed theater as a way to involve learners in the use of real discourse. Improvisation as part of theater allows individuals to learn from an experience that involves them intellectually, physically, and intuitively (Spolin, 1963). In this way, improvisation has the potential to be meaningful, engaging, and authentic; it represents an experiential technique to promote language learning (Hodgson & Richards, 1966; Perone, 2011). Similarly, Kurtz (2011) explained that improvisation allows students to exercise problem solving involving their past experiences to produce a response in a given situational context. Moreover, improvisation fosters creativity, playfulness, and willingness to speak (Kurtz, 2011).

Theater and The E Theater

Theater in Education

Theater in education (TIE) started in Britain in the 1960s (Prendergast & Saxton, 2009). TIE has historically spread around the world and has opened the space for the creation of participatory programs that have been effective in approaching young audiences and producing an active engagement in their own learning process (Jackson, 2013). The E Theater has engaged its participants in language learning through performing arts.

Theater for language learning can be mainly seen in two forms. One in which a theater company presents plays in a foreign language to enrich its context and promote language learning (Vienna’s English Theater, 2017), and another one that is related to the implementation of applied theater as a way to develop the participants’ communicative competence. The E Theater encompasses both perspectives (Castillo & Gualdron, 2008).

Group Theater

Kubicki (1974) used the terms Ensemble Theater or Group Theater for a theater troupe made of non-professional actors that get involved in the setting-up of a play. The author identified four different ways to carry out the process of ensemble: A group guided by its director can get involved in the production of an existing creation; it can adapt a literary work to ensemble style; it can create an original script through improvisation; or it can engage in the making of an originally literary collective creation. The E Theater has mainly worked on the adaptation of previously written pieces. Nevertheless, the group has also made of improvisation a major device for the creation of short original performances. Pammenter (2013) presented participatory theater as a form of TIE that meets the needs and wants of young people and that allows them to exercise their values, experiences, opinions, and communicate these to the world.

Reader’s Theater

The Reader’s Theater is one of the most researched and well-known theater strategies for L2 learning; it has been shown to improve different aspects of the reading domain like the fluency and comprehension of texts. The Reader’s Theater can be defined as an expressive and dramatic reading of a script that may or may not include the following: props, staging, and costumes (Casey & Chamberlain, 2006; Chou, 2013; Clark et al., 2009; Lin, 2015; Peregoy et al., 2008; Ratliff, 2000; Tindall, 2012).

Teaching as Performing

Not only can language learners benefit from theater, but the teacher as a stage figure can get much from it, too. Sarason (1999) presented several arguments about why teaching should be seen as a performing profession, and why this view should be included in teaching programs. Teachers need to effectively deliver the curriculum to their audience: their students. He concluded that entering the traditional performing arts has huge implications for the teaching of a person (Burgess, 2012; Sarason, 1999).

The E Theater

The E Theater’s methodology follows four main phases: The first one is theater training, where the members have the opportunity to explore different theater workshops; the second one is where the members present, discuss, and choose the play they want to perform; the third one is where the literary piece is adapted by the members; and the fourth, in which the performance is put together, rehearsed, and finally presented to an audience. The whole process can last a semester or a year.

Method

The present study is of a qualitative nature. A longitudinal semi-structured survey based on pre-existing literature on the subject was applied at different points in time (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006). The data to be reported correspond to an interpretative-descriptive exercise in which the case studied was observed through the eyes of participants involved in the event (Bonilla-Castro & Rodríguez Sehk, 1997). Subcategories were obtained inductively from open questions, and individual and group interviews. Participants were purposefully chosen due to their relation to language learning or to theater, the duration of their participation in the group, or their country of origin.

Research Questions

The following are the research questions that guided this investigation.

Participants

The E Theater has had five theater directors from its foundation until 2017. We were its two founders (researchers), and have been its coordinators since its very beginnings. They all were participants of this study, along with 52 of the students who took part in the process in The E Theater, in one or several of its cycles, reaching a total of 59 participants. All the theater directors had majored in theater and one of them had an MA from a university in the UK. The students mostly belonged to undergraduate programs at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, four were studying German, three of them had master degrees, and one was in a PhD program.

Data Collection Instruments

Longitudinal semi-structured surveys, in-depth semi-structured interviews, and a semi-structured focus group were held with members of the pool of participants. Table 1 shows the relation between participants and data collection instruments.

Table 1 Participants and Data Collection Instruments

| Instrument | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Students’ only individual interview | 7 |

| Only survey | 37 |

| Only focus group, coordinators | 2 |

| Only focus group, student | 1 |

| Focus group, survey | 2 |

| Focus group, interview | 2 |

| Interview, survey | 3 |

| Total number of students | 54 |

| Director interviews | 5 |

| Total number of participants | 59 |

The first phase of data collection for this study was carried out during the second academic semester of 2013, and the first of 2014. A second phase of data collection took place during the first academic semester of 2017. The first phase relates to the existence of The E Theater from its origins in 2008 until the year 2014 and the second phase gives account of the processes carried out in the second semester of 2015 and during 2016. Within the study, students were designated a number, and the teacher-directors the letter P and a number to keep their anonymity. The coordinators acted as researchers and were not considered.

Findings

Through the process of categorization, we expected to find out how the methodology had contributed to develop or improve the participants’ L2 skills and competences compared to how they perceived them at the beginning of the process. The major categories were initially the productive and receptive L2 skills as well as the intercultural competence. Nevertheless, the responses of the participants led to the establishment of two other categories: the affective and the cognitive dimension of learners. The additional benefits and challenges of the methodology as well as the impact of the group in its context were also identified.

In the study, 15 students (28%) were majoring in or had already graduated from a modern language program, another 15 had studied English at a school with a low intensity, 13 (25%) had studied at a bilingual or high intensity language training school, and the rest had studied English at the university or language institutes.

When asked about their productive and receptive L2 skills, students in the surveys rated their own proficiency at the beginning of the process with The E Theater from one to four. Forty-eight percent of the students on average graded themselves Level 3, considering all of the aspects they were asked about in L2 (speaking, writing, reading, fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, confidence, and listening), followed by 32% who rated their skills at Level 2. Forty percent identified themselves with a high level of reading comprehension, and only 9% considered themselves to be at a low command level of the language on average in all the skills. However, 20% rated the area of confidence at a low level. With this analysis, we can see that most students considered themselves within the range of intermediate proficiency at the time of participation in the group.

When asked about the progress they had made through the group, 75% of the students on average rated themselves at Level 3 or 4 out of 4 regarding their advancement in all the language skills except for grammar and writing. Forty-six percent and 40% of the students rated grammar and writing at Level 2 or lower, respectively, showing that these skills were not addressed in the process as much as the others.

Participants stated that the process in the group had helped and addressed their L2 skills and competences enhancement (Gill, 2013). The sub-categories shown in Table 2 were pointed out in the open questions within the instruments.

Table 2 Subcategories of Skills Worked

Note. Subcategories and activities in the tables are ordered from the most mentioned to the least mentioned in the instruments. Authors cited had already identified the specified subcategories in their research.

Table 3 reports the specific exercises or activities that participants remembered helped them improve in the different aspects of L2 learning. Improvisation exercises were mentioned as enhancers of most L2 skill categories (Hodgson & Richards, 1966; Kurtz, 2011; Perone, 2011; Spolin, 1963).

When determining if students had met their goals within the group, we asked them what their initial objectives were and if they had accomplished them. They could choose several options or add their own. Seventy percent said they approached the group with the objective of exploring or practicing theater, 59.5% wanted to get involved in an extracurricular activity, 74.4% wanted to practice English, 57.4% wanted to improve their English, 12.7% wanted to know more about the language, and 36% wanted to extend their social circle. Ninety-three percent of the students stated they accomplished their objectives within the group.

Similarly, in regard to the language, students indicated some of the expectations they had for the work developed within the group. Among them were: finding high level English speakers to be able to practice with, improving their listening, improving their speaking, learning more English in general, increasing their vocabulary (Clark et al., 2009), and being in contact with the language (Herrera & Murry, 2016). Also, they expected it to be a nice space to learn English where they were able to lose their shyness or fear of speaking the language (Leisse, 2008; Skeiker, 2015). As a theater exercise, students expected to develop their capacity to act, to explore their artistic creativity, and to share it with other people, to learn about theater techniques, to improve their performing skills, to act in front of the public, to explore a new theatrical paradigm, to find good actors, to act on a more professional level, and to improve their corporal expression, voice, and communication skills in general (Busà, 2015; Gross, 1977; Ryan-Scheutz & Colangelo, 2004). Analogously, 92.5% of the students stated that they met their expectations of the process.

Participants in the group had different English proficiency levels. In the survey, 53% of the students stated it was an advantage, 19% stated that it was a disadvantage, and 38% stated they had a neutral position. Most students who saw it as an advantage stated that students with a higher level helped the others to better their English. Some students stated they enjoyed helping others to improve, and that they learned by teaching, strengthened their solidarity ties, and that the experience was also useful for their life. Some of them pointed out that having a variety of English proficiency levels in the group strengthened the formative value of the group, meaning it was not only a space in which to learn English (Perone, 2011). On the surveys, one student noted:

The more advanced people correct without being tough or offensive, and it is easy for them to explain some aspects of the language that beginners do not know. Learning happens in both directions, because the beginners learn and the others reinforce their knowledge. (S42)

Some of the students who chose the neutral position stated that a minimum level of English was required to be part of the workshops. They also mentioned that the participants with a high level did not advance in their English proficiency as much as the ones with a low level, and that if the difference in the levels is considerable, this could limit the acting and theatrical process. The students who thought having different proficiency levels was a disadvantage pointed out that by including low level students in the group lowered the quality of the plays to be presented.

Students also gave their opinions about including participants with experience and without previous experience in theater in the group: 95% of the students in the surveys stated that it was either an advantage or they had a neutral position in regard to it. Some of them mentioned that actors could learn from other actors, and that the idea of a star did not align with the pedagogical purpose of the group (Perone, 2011). In the study, 62.5% of the students reported to have had previous theater experience at the moment of joining the group but even though some students did not have previous theater experience, they were engaged in the process. P5 stated in her interview that theater is not discriminatory in terms of skills and everybody can do it.

Intercultural and Literary Competence

The group had as one of its main objectives to work with literary pieces to let participants be able to have contact with the language culture (Essif, 2011; Sobral, 2011). Sixty-six percent of the students in the surveys said the group met that objective. The intercultural competence inside the group was mentioned as one of the strengths of the project’s methodology. Table 4 shows the activities that according to the participants helped them work on their intercultural and literary competence.

One student commented on the interviews: “You just do not interpret a nurse; you interpret a nurse from that time, from that moment, and from that historical condition” (16).

Provided the evidence, we can affirm that a literary analytical approach to performing a play enhances the intercultural competence in L2 of the students involved.

Interest for L2 Learning

Sixty-four percent (31) of the participants responded that their interest in English had changed after their experience in the group. Eight students explained that the group had reaffirmed their interest in the language (Lin, 2015; Suárez, 2012; Tindall, 2012); another six said that the group made them realize they needed to improve their English, and five more stated it helped them approach the language more easily because of the need to use it. For instance, one student commented: “My participation in the group reaffirmed my inclination for the language and evidenced my weaknesses” (S18). Moreover, 68% (33 participants) stated they felt more inclined toward theater than before (Lepper & Henderlong, 2000).

Additional Benefits

Throughout the years, students have repeatedly mentioned to us that the group has brought benefits in many other different areas of their lives. When participants were asked to say an adjective that described their experience within the group, 96% used positive adjectives. Some of the mostly used were: interesting, enriching, creative, excellent, learning, challenging, exciting, motivational, positive, dynamic, interactive, and intense. Ninety-eight percent (48 participants) established they greatly appreciated the social ties and environment created inside the group (Chesler & Chesler, 2005; Ortuzar, 2014; Shosh & Wescoe, 2007). Sixty-nine percent (34 participants) reported they found an emotional benefit in the group; many of them stated they felt appreciated, respected, and accepted in the group, and the space provided emotional relief for them. They also mentioned that it was an inspirational experience, and the group generated a sense of belonging and trust (Pammenter, 2013). Fifty-one percent (25 participants) said they felt more confident personally and 14% (7 participants) said they improved their communication skills (Busà, 2015; Gross, 1977; Ryan-Scheutz & Colangelo, 2004). Nevertheless, the second aspect with the largest participation was the professional. Seventy-five percent (37 participants) pointed out the benefits of theater as a pedagogical tool for teachers (Sarason, 1999). The students and professionals in foreign languages and philology reported great benefits from theater that could be implemented in their teaching of a second language. One student commented in relation to this:

The fact that you get into the classroom and it is not to see a video beam and a teacher who is far away, but instead you get to a classroom that does not have chairs, and we come here to play with each other, to connect as human beings, and to generate a collective project. From that point, it is already changing even my subject as a student. (S16)

Another student mentioned: “Using theater for bilingualism gave to me tools for my job in the US; I put together plays in English” (S15).

Other aspects of the group’s methodology identified as assets by the participants in the interviews were: cooperative and collaborative work (Perone, 2011), the values proper to the group like respect, love, friendship, a spirit of growing together, and the good treatment of others regardless of their English skills or proficiency. Many students talked about the creation of tight and meaningful social interactions and relations with others (Piaget, 1974; Pritchard, 2013). They also highlighted that it had a strong coordination and administration.

Impact on the Context

Nine participants stated that the impact of the group inside the university community was related to fostering the motivation and inclination for the language. Five students mentioned it represented a different way for learning English, 13 participants noted that the major impact was the group’s interdisciplinary nature that joined students from different fields around a learning experience; additionally, four students mentioned it increased the cultural panorama of the university. Suárez (2012) reported the creation of similar applications in other languages inside the University by former members of the group. Other students mentioned as an important aspect that it was free of charge, and the need for it to stay sponsored by the university as part of the benefits offered to the students.

One student, majoring in psychology and anthropology in two universities commented:

I think it is nice as a formative space that can make you lose your fear for English. If you see the level of English at the university, personally, I think it is very low, compared to other universities that demand a TOEFL. Universidad Nacional de Colombia takes you to a fourth intermediate level and people accomplish their graduation requirement but you do not see them confident about their English. Then, this is something we can do as students to contribute in this aspect. (S16)

Another student stated: “It helps us see that English is ours, not only something that belongs to developed countries” (S50). While another one pointed out: “University groups are important because everybody gives from their own careers and their experience is vital” (P2).

With the intention of observing the impact of the shows in L2 for the university community, participants were asked if they thought the shows benefited the audience: 72% agreed with the statement. They expressed in the interviews that the shows made the audience realize the pertinence of English. One of the directors (P5) stated that in the forums after the shows the comments were generally positive. The director stated that the exercise was very beneficial for the actors and for the audience who were all exposed to different pronunciations, made the effort to understand, and were doing the exercise of correcting what they were hearing at the same time. Another director stated that it was an exercise of public interest (P3), and it was successful because, “we had full house, and nobody stood up and left the auditorium” (P3).

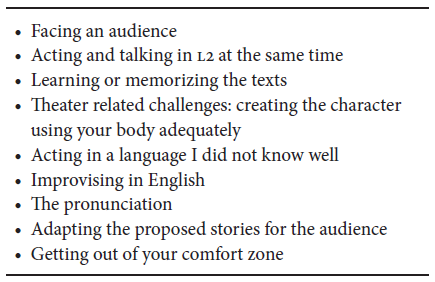

Challenges

Many students described their experience as challenging. Nevertheless, at the end they felt rewarded by having accomplished their goal. The challenges identified are shown in Table 5.

More specifically, a student wrote,

You have to think how you have to say it, or you have to think, how you need to be standing, or the expression you need to have…to me, I liked it, it was the challenge of fusioning everything. (S7)

Another student added,

Memorizing the script in a foreign language, to be able to understand the jokes proper of the culture that we were representing and correcting the pronunciation. (S57)

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The following discussion seeks to present a definition of the The E Theater’s methodology and to summarize the linguistic and nonlinguistic effects for its participants.

Defining the Methodology

The relevance of the application of The E Theater as a language-theater laboratory for English language learners is related to the benefits shown in the multiple language acquisition areas involved. Since the methodology of the group is cyclical, it allows for the interaction of new elements every time the process starts, and the trial of many different theater techniques. Additionally, the methodology used consists not only of theater training and workshops, but also the traditional Reader’s Theater approach. The time upon which the product is built is usually longer than in most other studies done and based on drama methodologies. The E Theater application allows the students majoring in modern languages to grasp theater elements and incorporate them into their own future teaching practices. At the same time, English language students are supporting the language learning process of their peers majoring in other fields. The traditional teacher figure and class is decentralized, and a more interactive approach takes place. The group lets participants help one another in the tasks proposed. Students majoring in languages have in the group a possibility to experience theater for language learning with real subjects, enriching in this way their pedagogical and professional perspectives. Figure 1 shows the synthesis of the most important elements of the group’s methodology.

Effects and Benefits for the Participants

The present study supports the affirmation that theater and acting techniques can be used to exercise an interactional, experiential learning and acquisition of different L2 skills and competences.

The theoretical framework presented is reinforced by the findings of this study by which reading, writing, listening, speaking, vocabulary, fluency, the intercultural competence of language, and the affective dimension of learners as well as the comprehension process of the language can be addressed. Theater’s major contribution seems to be that it lowers learners’ affective filter through understandable input since it provides scaffolding for their understanding, and a personal challenge within a cooperative and collaborative environment.

Individual and group improvisation exercises constitute an important resource for learners to experience the vivid use of the language, and hence theater techniques are valuable resources that teachers of languages can exploit in their own classes. Furthermore, participants derived professional, emotional, and social benefits from their experience in the group. The study also showed evidence that team work, cooperative, and collaborative methodologies are engaging and rewarding for students; the theater ensemble promotes community building and the creation of strong personal connections.

In summary, The E Theater’s methodology is an application that reinforces the idea of theater as a holistic discipline to address through different exercises and group dynamics, important aspects of language learning.

Validity and Further Research

The population of this study was quantitatively representative. Between 70 and 83% of the students who participated in the longest processes carried out by the group made part of the study. They experienced the methodology for at least two semesters, four hours a week, plus extra rehearsals to polish the final products. All teacher-directors participated in the study.

Conclusive descriptive statistical data were found in most categories explored, at different points in time, and it was accompanied by voluntary participants’ descriptions or voices that allowed the understanding in detail of the phenomenon of language learning through theater. Similarly, the categories of analysis were found simultaneously at different points of the data collection and in more than one of the instruments used allowing their triangulation.

The value of this study relies on its pertinent and highly critical context, and in the length of the phenomenon studied. Further quantitative research can be done in regard to specific categories and subcategories presented in this study.