Introduction

Transition care is defined as efficient and safe coordinated practices to ensure continued care at home. It aims to prevent complications and hospital readmissions and reduce communication gaps, making it a challenge to develop instruments that operationalize the transfer safely (1, 2). Therefore, a coordinated care plan to ensure improved quality of life for patients and reduced length of stay and readmission rates for adults with complex medical needs has a key role in fulfilling the health needs of patients, caregivers, and society as a whole (3, 4).

However, transitions between healthcare services and households can represent a period of extreme vulnerability, especially for patients with multiple comorbidities, complex treatment regimens, or limited support from informal caregivers, due to the structure inherent to the primary healthcare network, which is limited in providing direct care to these patients, as it has a reduced number of professionals and equipment needed for home care. In this sense, practices that aim to improve the management of hospital discharge can demonstrate a more thoughtful approach to the transition of care (5). For this study, “informal caregiver” was defined as someone who has the role of providing care and may or may not have family relations with the patients (6).

Although the dehospitalization policy has been in effect since 2013 through Ordinance 3.390 of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, aiming alternatives to hospital practices, it is important to note that progress is still needed in this process and that there is a deficiency of action planning and communication among the multi-professional teams within the hospital inpatient sectors (7).

With the aim of raising awareness amidst healthcare professionals and services about the challenges faced by patients and caregivers during discharge transitions, new strategies need to be developed that focus primarily on discharge planning practices and preparing patients for the transition (8). Thus, the development of tools such as checklists can improve healthcare, systematize care, assist in carrying out complex routines and increase patient safety, with the potential to reduce costs, wasted time, and rework for the professionals (9, 10).

In this context, the creation of a guidelines checklist for hospital discharge assists in the diagnosis of flaws in the process, correcting communication gaps during the hospitalization period, promoting the possibility of training, and providing guidelines to informal caregivers for the necessary continued care at home for patients with technology dependence and multiple comorbidities. The aim of this study was therefore to develop and validate a checklist to support nurses in guiding home care for adult patients to informal caregivers during the hospital discharge transition process.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Aspects

The study was conducted in compliance with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council. The project was submitted to the Commission for the Regulation of Academic Activities, with authorization 009/2022, and then to the Standing Committee on Ethics in Research with Human Beings, with authorization no. 5.358.567. All participants signed an informed consent form (ICF).

Design, Study Site, and Study Period

This is a methodological study, grounded on the Delphi methodology as a content and presentation validation technique. The study was performed in a city in the northwest of Paraná, Brazil, from February 2022 to January 2023 (11, 12).

Study Participants and Inclusion Criteria

The judges in the study were selected according to the Fehring model, scoring at least 5 points according to the following criteria: Having a PhD - 4 points; having a master’s degree - 3 points; having completed a dissertation or thesis in the field of interest - 3 points; being a specialist in the field - 2 points; having published in an indexed journal on the subject of interest - 1 point; having clinical practice in the field of interest for at least one year - 2 points; and having participated in research groups/projects involving the field of interest - 1 point. In the present study, experience in the study’s field of interest was considered to be the following: Hospital discharge management, dehospitalization, care transition, informal caregiver, instrument development and validation, and health education (13).

Data Collection and Organization

Situational Diagnosis

A literature review was conducted to explore the theme of hospital discharge transition and continued care at home. The research question for this review was “What are the publications related to methodological studies for continued care in the transition from hospital discharge focusing on informal caregivers?” (14, 15).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 Distribution of the Research Rteps for the Preparation and Validation of the Checklist. Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2023

The search strategy was performed on the following search platforms: The US National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health (PubMed), Virtual Health Library (VHL), and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search for the articles was done by cross-referencing the controlled descriptors found in the health sciences descriptors (DeCS) and the medical subject headings (MeSH), using the Boolean operator “AND” in varying combinations: “cuidadores informais” (“informal caregivers”), “estudo metodológico” (“Methodological study”),“continuidade da assistência” (“continuity of patient care”), “transição de alta hospitalar” (“hospital to home transition”); including texts in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, during June 2022.

The inclusion criteria for the studies were original studies, performed with an adult population over the age of 19, available in full, in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, published after 2013, with this date being warranted due to the implementation of Ordinance 3.390 issued in December 2013, which instituted the National Hospital Care Policy, within the scope of the Brazilian Unified Health System, establishing the implementation of responsible hospital discharge. The exclusion criteria were non-primary articles, such as opinion pieces, letters to the editor, short communications, and editorials (7).

Checklist Development

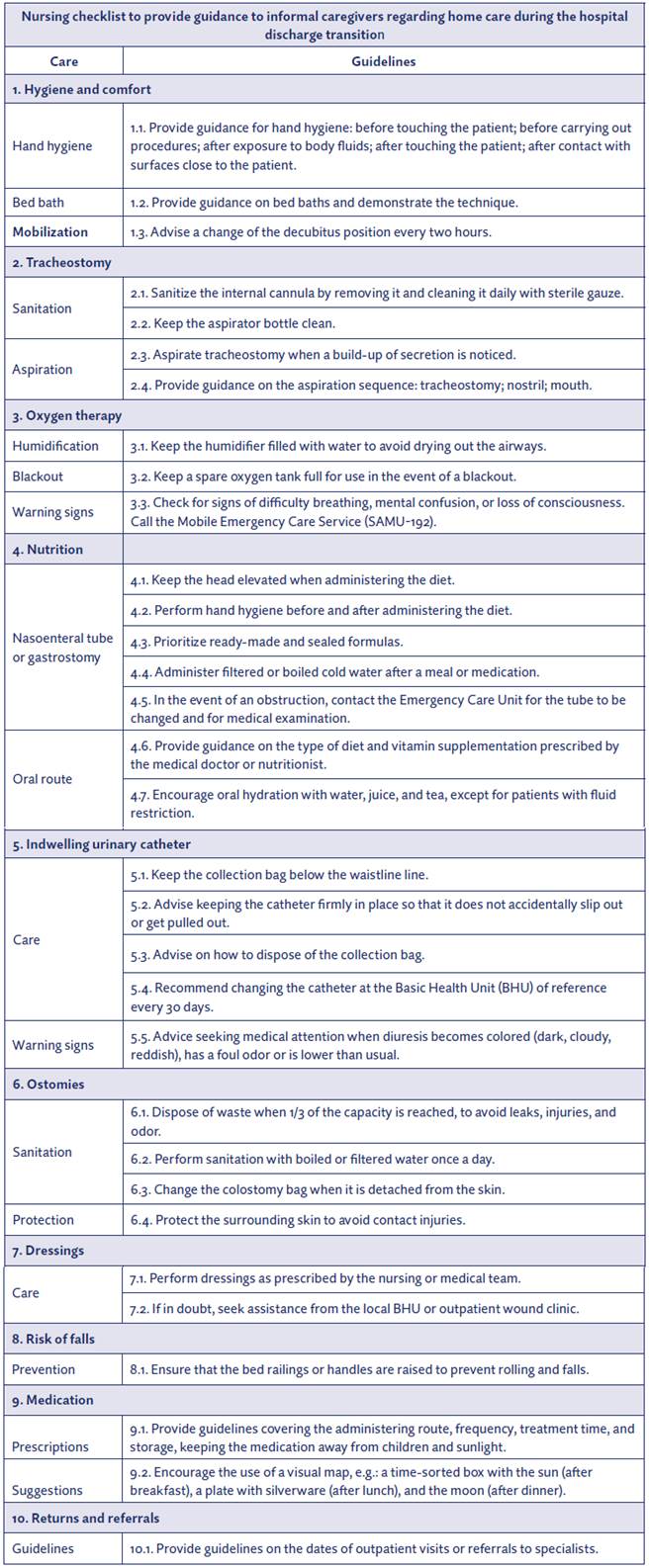

The checklist development was categorized as follows: 1 - hygiene and comfort; 2 - tracheostomy; 3 - oxygen therapy; 4 - nutrition; 5 - indwelling urinary catheter; 6 - ostomies; 7 - dressings; 8 - risk of falls; 9 - medication; 10 - returns and referrals. In addition, it was based on the studies found in the literature review and used as its theoretical foundation the categories of the Katz and Lawton scale, which assess the general daily life activities, and the empirical elements of professional practice. The classification of the items incorporated the main care to be provided by nurses to informal caregivers to ensure the transition to hospital discharge and continued care at home, as shown in Figure 2 (16).

Checklist Validation

Presentation and content validation followed the guidelines outlined by Pasquali (2010), with a minimum of seven specialists (17) being included in this study. The Delphi technique was then used, divided into the following stages: 1st - choosing the group of specialists; 2nd - developing the judges’ evaluation instrument; 3rd - first communication with the specialists, inviting them to participate in the research; 4th - sending out the first checklist; 5th - receiving the responses from the first round of evaluation; 6th - qualitative and quantitative analysis of the responses; 7th - preparing and sending out the second checklist with feedback; 8th -receiving the responses from the second checklist and analyzing them; 9th - concluding the process with the development of the final version of the checklist (11, 12, 18).

Fourteen nurse judges were selected, who received online invitations explaining the study objectives and, after accepting it, they were sent the evaluation instrument, the ICF, and the checklist, with a deadline of 15 days for their response. Of the 14 judges selected, 9 responded to the first evaluation and 5 to the second. The assessment was performed by responding to a structured questionnaire in the form of a Likert scale, in which the answers were classified as follows: 1 - inadequate, 2 - partially adequate, 3 - adequate, and 4 - totally adequate. The checklist was evaluated in terms of objectivity, content, language, relevance, layout, motivation, and culture, and consisted of 29 items (19, 20).

Data Analysis

The data collected from the judges were compiled in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet, transcribed, and then submitted to statistical treatment using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 27.0). The content validity index (CVI) was applied to the total and the items to assess the agreement between the judges, adding up the items that scored 3 or 4 on the Likert scale and dividing by the total number of responses. The index of acceptable agreement between the judges was considered adequate when it reached a score > 0.80 (21, 22).

For the reliability analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used, which is intrinsically related to the number of items in the scale and was considered “adequate” when the score was > 0.80 (23), as well as the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to assess the level of agreement between two or more judges when using the same assessment scale. For this study, an ICC > 0.75 was considered adequate (21, 22).

After the instruments from the first assessment round were sent back, the descriptive statistics of the proposals and the analysis of the suggestions for changes/reformulation of the items from the first assessment stage were carried out; the SPSS program, version 27.0, was used to process the data.

Therefore, according to the results obtained, a checklist was developed based on the judges’ suggestions and a second round of evaluation was proposed. After the second analysis, the evaluation and analysis process were completed.

Results

To develop the checklist, a literature review of the main existing methodological studies focusing on informal caregivers was used. The categories were divided according to the daily life care practices to be presented to the caregiver. The final version of the checklist consists of 10 domains (1 - hygiene and comfort; 2 - tracheostomy; 3 - oxygen therapy; 4 - nutrition; 5 - indwelling urinary catheter; 6 - ostomies; 7 - dressings; 8 - risk of falls; 9 - medication; 10 - returns and referrals), distributed into 32 guidelines, ranging from basic care to emergencies to provide guidelines on which services should be sought in each of them (Figure 2).

Table 1 Statistical Summary of the CVI Analysis, by Items, from the Guidelines Checklist for Informal Caregivers. Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2023

| Categories | Items | First assessment | Second assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVI* | Interpretation | CVI* | Interpretation | ||

| Objectives | 1 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 2 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 3 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 4 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Content | 5 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 6 | 0.66 | Not Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 7 | 0.77 | Not Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 8 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 9 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 10 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 11 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 12 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Language | 13 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 14 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 15 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 16 | 0.66 | Not Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Relevance | 17 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 18 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 19 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 20 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 21 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Layout | 22 | 0.77 | Not Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 23 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 24 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 25 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| 26 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Motivation | 27 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

| 28 | 1.00 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable | |

| Culture | 29 | 0.88 | Acceptable | 1.00 | Acceptable |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

In the items that presented CVI < 0.80 -6 (CVI = 0.66) and 7 (CVI = 0.77), as described in Table 1, referring to the categories of content, clarity, objectivity, and adequacy to the scientific standard, the judges proposed changing some scientific terms, such as correcting the decubitus position change interval from 3/3 to 2/2 hours in item “1 - hygiene and comfort,” sub-item “1.3.,” in line with the scientific framework. Regarding tracheostomy cleaning in item 2, it was requested that the procedure be better specified so that it would be described as performing hygiene of the internal cannula by removing and cleaning it daily with sterile gauze in sub-item “2.1.” In addition, the instruction to discard the tube after each aspiration was removed, as some cities only provide one tube per day.

Regarding item 3, “oxygen therapy,” there was a change in the guidelines in sub-item “3.3.” regarding cardiorespiratory arrest at home, as the judges considered it to be an item that needed more time for guidance and an adequate location; thus, this item was changed to warning signs and measures until the arrival of the Mobile Emergency Care Service. The expression “tube washing” in the “nutrition” category, item 4, “nasoenteral tube,” sub-item “4.4.,” was replaced by “administer filtered or boiled cold water with each medication,” which is more scientifically suitable.

Similarly, considering the restriction of fluids in the oral route diet for chronic kidney disease, sub-item “4.7.” was replaced with a fluid-restricted diet, as there are other situations in which fluids are restricted. The guidelines on care for the risk of falls in item 8, sub-item “8.1.,” “keep the railing raised,” was replaced by “keep protections or barriers in place” because of the absence of hospital beds at home environments, which requires to adapt care to the home setting. Regarding medication, in item “9,” guidelines were added regarding the storage of medication, in sub-item “9.1.,” to keep it out of the reach of children and away from sunlight.

When evaluating the instrument for clarity and objectivity, the judges proposed avoiding the repetition of expressions such as “guide the caregiver” and “inform them about” at the beginning of sentences.

Regarding items “6” and “7,” in terms of content, and item “16,” in terms of the language used in the instrument, Table 1 shows a CVI = 0.66, which was therefore not acceptable during the first evaluation. According to the judges, the writing style used was too technical to be understood by informal caregivers. However, it was noted that the judges had misinterpreted this, as they assessed it as if the caregivers were the target audience, while in reality healthcare professionals would be the ones using the checklist in their practice.

Considering the layout of the instrument, in item “22,” which was also assessed as not acceptable with a CVI = 0.77, the judges proposed changing the colors, font type and size, and the division between categories and items, making it more attractive and organized for professionals to read and use.

It can be noted that the categories “objective,” “relevance,” and “motivation,” in both rounds, presented a CVI = 1.00; the “culture” category, in the first round, presented a CVI = 0.80, and no adjustment was necessary in these items.

After receiving all the corrections suggested by the judges, it was noted that all the items had been considered acceptable by the judges in the second evaluation. The summary of the CVI analysis is detailed in Table 1.

The analysis of the Cronbach’s Alpha scale (23) is detailed in Table 2. Regarding the “objectives” category, which consists of four items, the judges’ first evaluation resulted in an Alpha of 0.81, with an average ICC of 0.8 (p = 0.001). After the suggested corrections, this category scored an Alpha of 0.85 in the second assessment, with an average ICC of 0.7 (p = 0.020). The “content” category, consisting of eight items, and the “language” category, consisting of four items, had an Alpha of 0.82 and 0.84, respectively, and an ICC of 0.8 in the first assessment, showing a significant improvement, with an Alpha and ICC of 1.00 in the second round.

Table 2 Summary of the Reliability Analysis of the Guidelines Checklist Scales for Informal Caregivers, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2023

| Categories | items | First assessment | First assessment | Second assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α* | x ICC † (95CI)‡ | p§ | α* | x ICC † (95CI)‡ | p§ | ||

| Objective | 4 | 0.81 | 0.8(0.4;0.9) | 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.7(0.5;0.9) | 0.020 |

| Content | 8 | 0.82 | 0.8(0.4;0.9) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00 ( - ) | - |

| Language | 4 | 0.84 | 0.8(0.5;1.0) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00 ( - ) | - |

| Relevance | 5 | 0.32 | 0.3(0.7;0.8) | 0.188 | 0.92 | 0.7(0.3;0.9) | <0.001 |

| Layout | 5 | 0.85 | 0.8(0.5;1.0) | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.5(0.1;0.9) | 0.016 |

| Motivation | 2 | 1.00 | 1.0(1.0;1.0) | - | 0.86 | 0.8(0.2;0.9) | 0.016 |

| Culture | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| instrument | 29 | 0.86 | 0.9(0.7;1.0) | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.8(0.1;0.9) | <0.001 |

*: α : Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient †: ICC: Intraclass correlation coefficient

‡: 95 % CI: 95 % confidence interval §: asymptotic significance of the test; significance level of 0.05

x : mean

Source: Prepared by the authors.

In the “instrument relevance” category, consisting of five items, a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.32 was obtained, with a mean ICC of 0.3 (p = 0.188), which was not statistically significant. Then, after the suggested corrections, in the second assessment, this category scored an Alpha of 0.92, with a mean ICC of 0.7 (p = < 0.001), which was significant. The “layout” category scored an Alpha of 0.85, with a mean ICC of 0.8 (p = <0.001), which was significant; after the suggested corrections, the Alpha changed to 0.80, with a mean ICC of 0.5 (p = 0.002); as it was an isolated item, it was decided to assess the items and instruments as a whole, not considering the data separately.

In the “motivation” category, an Alpha of 1.00 was assigned in the first assessment and 0.86 in the second assessment, with a mean ICC of 1.0 and 0.8; regarding the “culture” category, it was not possible to assess this item as it was unique and there were no possible comparisons.

The checklist assessed in its entirety consisted of 29 items in the first version, divided into the categories “content,” “language,” “relevance,” “layout,” “motivation,” and “culture,” and obtained a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.86 with a mean ICC of 0.9 (p = < 0.001). After the suggested modifications, the instrument consisted of 32 items and, in the second assessment by the judges, received an Alpha of 0.84, with a mean ICC of 0.8 (p = < 0.001), being considered a reliable instrument for use in clinical practice, with a high agreement correlation between the judges and intraclasses. The final version of the checklist is shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

The checklist developed can be used as a tool for the daily practice of professional nurses in the hospital discharge transition to facilitate the assessment of the informal caregiver’s needs during hospitalization and to enable them to develop strategies for guiding care in the discharge transition, thus facilitating continued care at home. Therefore, nurses are facilitators in the discharge transition process for informal caregivers, by accompanying them, guiding them, and training them to develop new skills (24).

There is a consensus that the caregiver’s emotional, physical, social, and financial burdens lead to challenges in providing care, who often lack any knowledge of special techniques and care, which can lead to complications and readmissions, and affect the prognosis of the disease (2, 3, 25).

Thus, apart from facilitating communication, these tools function better when they are included in an electronic system that is easily accessible to the teams, alongside the medical records. Moreover, the use of checklists by healthcare professionals manually ensures that all the guidelines are followed, and when they are followed electronically, they offer increased security in the procedures, optimizing the professionals’ time (26-29).

In this sense, the checklist uncovered gaps in knowledge and care, regarding planning and multidisciplinary communication. The absence of guidelines for informal caregivers and communication between the care team leads to post-discharge problems, such as complications in home care and readmissions due to misinformation about the care to be provided, among others. Therefore, the use of a validated checklist can promote more effective communication in hospital discharge planning (32).

Therefore, the selection of judges using Fehring’s method provided an adequate selection, thereby enabling the development of a contextualized checklist (13). The validation via the Delphi technique allowed for the selection, assessments, and suggestions of the judges, in addition to improving the content and structure of the checklist. The analysis carried out validated the checklist to meet the guidelines needed for discharge planning in the transition of care (11, 12, 18, 33).

Regarding content and presentation, the checklist achieved excellent agreement between the judges, with a CVI of 100 %, ensuring that it is an instrument that can be used in professional and scientific practice and responds adequately to what has been proposed (19-22).

In a similar study addressing the development and validation of an educational booklet for caregivers, the importance of making caregivers the protagonists of their own care is emphasized, since they often give up their own lives to care for others. Although this booklet focuses on the informal caregiver in both instruments, it is entirely dedicated to providing care to the caregiver. In the present study, on the other hand, the caregiver assumes the role of the protagonist in the care of patients who depend on technology and complex care, with a checklist to help nursing professionals to train them in home care (30).

Thus, Cronbach’s Alpha and the ICC demonstrated that this checklist is a highly reliable and structurally suitable instrument, which ensures a robust quality assessment (23, 31). Therefore, this study provides a reliable tool, based on scientific evidence, which can be used safely in clinical practice, in addition to sparking further complementary research.

Study Limitations

The limitations of this study include the small number of judges, given that there was only one professional category of judges from the same region. Furthermore, the type of questionnaire used to evaluate the judges (online) could lead to the instrument’s misinterpretation and response bias. To minimize bias, the judges were briefed on the purpose of the survey, the target audience of the checklist, and the feedback from the first analysis.

Conclusions

The checklist presented relevant and valid content regarding its objectives, presentations, structure, organization, relevance, and didactics. It is a fairly useful tool for the work of the nursing team, as a strategy for identifying the caregiver’s needs and providing timely training during hospitalization. Furthermore, aside from optimizing communication between teams, it promotes a safe transition and continued care at home. It can therefore be used in scientific settings, with reliable and meaningful data.

However, further studies are suggested on the usability of the checklist by nurses, assessment of its application for a safer discharge transition, as well as assessment of continued care at home, with increased quality and safety, which could contribute to a reduction in readmission rates.

text in

text in