Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.7 no.2 Medellín July/Dec. 2014

Research

A passionate way of being: A qualitative study revealing the passion spiral

Una forma de ser pasional. Un estudio cualitativo que revela la espiral de la pasión

Susanna M. Halonen a,*, and Tim Lomas a,

a School of Psychology, University of East London, London, United Kingdom.*Corresponding author: Susanna M. Halonen, School of Psychology, The University of East London, Stratford Campus, Water Lane, London, E15 4LZ. Mobile +44 7564 397437. Email address: susanna@happyologist.co.uk

Article history: Received: 08-05-2014 - Revised: 20-06-2014 - Accepted: 05-07-2014

ABSTRACT

Being engaged in an activity one is passionate about has been tied to feeling life is worth living for. Existing research in passion has explored this phenomenon purely using quantitative research methodology, and by tying an individual's passion to a specific activity. In this study, passion was explored in semi-structured interviews with 12 participants. The qualitative grounded theory analysis revealed a passionate way of being, with passion being located in the individual rather than in a specific activity. A new phenomenon to positive psychology, a passionate way of being is about having a purpose, creating positive impact, and pursuing variety. These key elements, amongst others, created a reinforcing, self-sustaining spiral, which offered a route to hedonic and eudaimonic happiness, generally serving to enhance life (though it could also detract from life if it became overpowering).

Key words: Passion, passionate, way of being, happiness, qualitative research, grounded theory.

RESUMEN

Estar involucrado en una actividad que resulta apasionante ha estado ligado a la sensación de que la vida vale la pena. Las investigaciones existentes acerca de la pasión han explorado este fenómeno usando solamente metodologías de la investigación cuantitativa. En este estudio, la pasión fue explorada en entrevistas semi-estructuradas con 12 participantes. El muestreo teórico cuantitativo reveló una forma de ser pasional en la que la pasión estaba localizada más en el individuo que en la actividad específica. Un nuevo fenómeno para la sicología positiva, una forma pasional del ser, consiste en tener un propósito, creando un impacto positivo y buscando variedad. Estos elementos clave, entre otros, crearon un fortalecimiento en forma de espiral auto-producente que permite una ruta hacia la felicidad hedónica y eudaimónica, la cual es generalmente útil para mejorar la calidad de vida (aunque también podría disminuirla si se intensifica demasiado).

Palabras clave: Pasión, pasional, forma del ser, felicidad, investigación cualitativa, muestro teórico.

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel field of positive psychology explores how individuals, organisations and communities thrive (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). A component of individual thriving is feeling life is worth living for (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Vallerand and Verner-Filion (2013) suggest being engaged in an activity one is passionate about makes life worth living. Vallerand et al. (2003) define passion as a strong desire towards a self-defining activity one loves, invests energy in, and finds important (Vallerand et al., 2003). The existing research on passion has measured passion together with person-environment fit model (Amiot, Vallerand & Blanchard, 2006), adaptation behaviour (Mageau et al., 2009), performance (Vallerand et al., 2007), flow (Carpentier, Mageau & Vallerand, 2012), strengths (Forest et al., 2012), self-esteem (Lafreniere, Bélanger, Sedikides & Vallerand, 2011) and wellbeing (Bonneville-Roussy et al., 2011; Philippe et al., 2009; Rousseau & Vallerand, 2008). These quantitative studies have tested and often supported Vallerand et al.'s (2003) Dualistic Model of Passion, presenting harmonious and obsessive passion, and its accompanying Passion Scale. However, these quantitative studies have not substantially explored what the manifestation of passion in one's life actually looks like, from how it is experienced to what it means to the individual to what the individual's motivational drivers behind passion are.

They have also limited the study of passion's positive effects to subjective wellbeing, positive affect, and meaning in life (Bonneville-Roussy, Lavigne & Vallerand, 2011; Rousseau & Vallerand, 2008), without giving the study participants any room to elaborate on what is it about the experience of passion or having a passion that is accompanied by these positive effects. It can be argued these unanswered questions are the result of using purely quantitative research to explore passion, as confirmed by Vallerand, the founding father of passion research, who said he had "not seen any passion research using a qualitative approach" (R.J. Vallerand, personal communication, February 13, 2013). As pointed out by Henwood and Pidgeon (1992), qualitative research is more exploratory and open to new insights than quantitative research. Based on these points, this study's objective was to redress these questions, and fill the black hole on what the experience of passion is all about. The findings of this qualitative research piece makes this study the first to view passion as a way of being (inherent in the person), rather than enthusiasm for a particular activity.

Philosophers have appraised passion in both a negative and positive light for thousands of years. Plato (429-347 BC), and later Spinoza (1632-1677), argued that passion led to animal like behaviour and unacceptable thoughts, with individuals as slaves to their passion (Rony, 1990). Conversely, Aristotle presented passion as a reflection of eudaimonia, personal expressiveness through one's true self which empowers one's highest potential and fulfilment (Waterman, 1993). The idea of eudaimonia has been embraced in positive psychology as 'eudaimonic wellbeing' (Ryan and Deci, 2001). Contemporary research (e.g. Vallerand, 2008; Vallerand et al., 2003) suggests that passion can contribute to the fulfilment of potential that is encompassed within eudaimonic wellbeing, but does not explain how this contribution happens. The findings of this study shine light on how the participants felt connected to their fulfilment of potential through pursuing the passionate way of being. Since both negative and positive appraisals of passion exist in philosophy, it is fitting the Dualistic Model of Passion also presents two perspectives (Vallerand et al., 2003).

Vallerand et al.'s (2003) Dualistic Model identifies two types of passion: harmonious and obsessive. Harmonious passion is driven by autonomous internalisation of the activity, i.e., the choice to pursue the activity for the sake of enjoyment, and results in flexible persistence. Conversely, obsessive passion is driven by controlled internalisation of the activity, i.e., compelled by internal (e.g. uncontrollable excitement) or external pressures (e.g. peer acceptance) to undertake the activity, and results in inflexible persistence (Bonneville-Roussy et al., 2011; Vallerand et al., 2003). The model outlines two types of passion, but does not outline whether it is possible to be 'multi-passionate', and experience passion towards many different activities. Mageau et al. (2009) and Schlenker (1985) dispute that as passion becomes a central feature of one's identity, people don't merely dance, paint or swim; they are dancers, painters and swimmers. Where does this leave people who love to dance, play with dogs, read books and cook? Are they a dancer, dog-lover, reader and chef? This is an area which no existing research has touched on, and this study provides an answer to this by viewing passion as way of being, suggesting that certain individuals live their whole lives with passion rather than tying it to an activity they feel enthusiasm towards.

The model also fails to acknowledge how tendencies towards these two different types of passion might develop. However, one recent study has examined this enthusiasm towards an activity from a developmental perspective, albeit with quantitative analyses. Mageau et al. (2009) explored a passion's development through three studies using correlational and short-term longitudinal designs. The first involved 229 adults committed full-time to their passionate activity. The second included 163 children who had engaged in deliberate practice of a specific activity for a few months. The third consisted of 196 high-school students who had just started an activity. The three studies indicated passion's development was encouraged by: activity mastery, parental approval of activity, autonomy support, and identification with the activity. Although the correlational nature of the study prevents clear answers on causality, the findings are an informative first step in suggesting the developmental role of both internal (e.g. identification with activity) and external factors (e.g. parent's approval). Arguably, qualitative research is needed to explore these factors further, which is what the current study has done by identifying two motivational drivers and two developmental factors of the passionate way of being.

In addition to some examinations of the development of passion, scholars have explored the outcomes of passion. Philippe, Vallerand, and Lavigne (2009) discovered that people assessed as being harmoniously passionate scored significantly higher in both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing than obsessively passionate and non-passionate people. These findings indicated that harmonious passion contributes to happiness and pleasure (i.e. hedonic wellbeing), as well as meaning in life and self-realisation (i.e. eudaimonic wellbeing) (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Vallerand, 2008). Similarly, Bonneville-Roussy et al. (2011) found that harmonious passion predicted higher hedonic wellbeing. As these studies were also quantitative, qualitative research is needed to explore these outcomes in more depth to discover how the experience of passion contributes to both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Thus, employing qualitative methods, the current study is able to provide a richer understanding of the origins and outcomes of passion in people's lives. Expert speakers were identified as a suitable population as these speakers had spoken at a conference on a theme they were passionate about. The research question was: What role does passion play in expert speakers' lives? Due to the qualitative nature of the study, and the use of grounded theory methodology, no hypothesis to the study was assigned in order to minimise researcher and participants bias.

2. METHOD

2.1. Design

Twelve participants were individually interviewed, using semi-structured interviews, to examine the role that passion played in expert speakers' lives. Grounded theory (GT) methodology was used for data analysis. Glaser and Strauss (1967) define GT as collecting, integrating, analysing and conceptualising qualitative data to create a theory. More specifically, the analysis used Charmaz's (2007) social constructivist approach to GT (in which the findings are viewed as the result of the interaction between the participants and the researcher). The researcher took a critical relativist epistemological framework, understanding the participant and researcher may influence each other throughout data collection (Anderson, 1986).

2.2. Participants

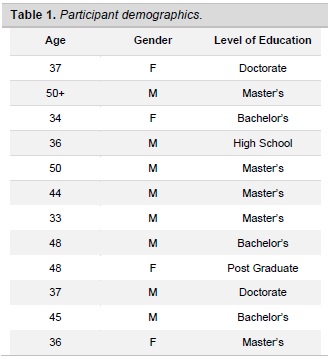

Twelve participants were recruited by email from two locally organised conferences convened as franchise of the umbrella organisation, © TED conferences (with the motto 'Ideas worth spreading') (TED, 2013). The sample was homogenous in that the speakers gave a presentation on a topic that they were passionate about at one of these conferences, and in that most of the speaker's work was related to this topic. The sample was demographically heterogeneous, with both men (8) and women (4), and ages ranging from 33 to 50+ (with an average of 41.5) (Table 1). Their careers varied, including a consultant, comedian, energy researcher, musician, teacher and magician among others.

2.3. Interview procedure

The data was collected through semi-structured interviews, conducted in conversational style. An interview schedule, involving 10 questions (Table 2), was constructed based on existing research and gaps in current understanding around passion. Interviews lasted between 25 to 65 minutes, and were recorded with the participant's consent. The voluntary nature of their participation and their right of withdrawal was highlighted in the invitation sheet, verbally before the interview, in the consent form, and after the interview (during a verbal debriefing). To aid subsequent analysis, after each interview the researcher completed a reflexive memo, detailing how the interview went and any impactful memories concerning the participant's body language, behaviour, or comments.

2.4. Analysis

The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed, and details likely to lead to participant identification were redacted. The analysis followed GT principles, with analysis starting as interviews were still being conducted, and going deeper after all interviews had been completed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Throughout the study, the researcher wrote reflexive memos, acknowledging her cognitive processes may have influenced the data analysis (Anderson, 1986; Rennie, 2012). The analysis on each transcript started with explorative line-by-line coding, in which descriptive labels were created, interpreting each line of data. Focused coding followed, identifying higher order codes for larger text portions and categorising them. The third step involved comparative analysis between the codes and categories to identify prominent themes and sub-themes. Approximately four to eight themes, and five to ten sub-themes, were identified in each transcript. The comparative analysis of all themes and sub-themes across all transcripts resulted in the identification of one core underlying theme, a passionate way of being, and a representative model for the whole sample (Figure 1 in the discussion). Monthly meetings with the research colleague ensured the emerging analysis was continually and consistently reviewed. Although saturation appeared to have been reached after nine interviews, the three remaining interviews that had been scheduled were conducted to ensure saturation. Twelve interviews ensured the data was sufficient to cover the topic of passion in depth, and to ensure that individual variation was reflected in the emergent analysis (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2006).

3. RESULTS

The analysis produced one core theme: a passionate way of being, construed as passion being located in the individual, rather than in an activity they pursue. The participants spoke about directing their passion towards many things in life, and not to a specific activity. For example, Jane described the passionate way of being as inseparable from her, a motif which runs throughout her life: "Passion feels like it ought to be something that runs through you, and through your life, and it's integral to your identity".

Under the core theme were six themes with their unique sub-themes (Table 3). The themes will be discussed in turn, with exemplary quotes from participants (using participant pseudonyms). Although quantification of qualitative data is a contentious issue, theme prevalence is presented (Table 3) on the basis that it provides a useful overview of the analysis and a fair representation of the themes (Pope, Ziebland & Mayas, 2000).

3.1. A passionate way of being

Two components of a passionate way of being were identified: having purpose and being authentic.

3.1.1. Having purpose: Participants reported that having passion was fundamentally a matter of experiencing a sense of purpose in life, and having the drive to pursue this purpose. Participants had a clear sense of direction, giving them perspective about the relative importance of the various elements of their lives, helping them focus. As Tony explained: "When you're so clear about what's important to you and you've got that passion to drive you, then you don't get worried about little things". Moreover, following a purpose empowered participants to take an active sense of responsibility for shaping their lives, as Jane expressed: "What I get from passions… is you get a reason to make the journey, and you actually bother to take the journey... You're actually bothered to shape your journey". When the respondents understood their why, they were motivated to proactively take control of their lives. Having purpose was closely linked to another existential theme in the interviews: being authentic. These two interlinked factors reinforced each other as the central components of the passionate way of being.

3.1.2. Being authentic: The participants described pursuing their passion using the language of authenticity, in terms of "being true to yourself" (Sarah) and being "right at the heart of your core" (Tony). They saw their passion as central to who they were, as identity-defining. Thus, passion was depicted as a way of being. This depiction is fundamental to the data: rather than passion simply reflecting a positive appraisal of a particular activity, passion was construed as a quality of the self. More specifically, passion was portrayed as being a manifestation of living authentically, in accordance with one's values and beliefs. This passion was central to their existence. As Dan recalled: "I feel that when I am connected to myself, and I'm expressing myself fully, then I live my passion". When he was able to behave in a way that was true to him, he felt most connected to this passionate way of being.

3.2. Motivational drivers

The analysis showed the two main drivers of a passionate way of being were the desire to have a positive impact, and the drive to learn and grow.

3.2.1. Have a positive impact: In quantitative terms, the desire to have positive impact had the highest prevalence of the themes, being endorsed by all participants. Participants expressed this desire in many ways, including helping other people, ‘making a difference', and inspiring people. Tony spoke about admiring others who were "contributing to the world", and the way they had a drive "forward"; meaningfully, he now felt he had that drive, as he had found his way to contribute. Having a clear idea of how to contribute was closely related to the sense of having articulated one's purpose. Albert spoke about enabling people to realize their potential: "It's about empowering people to do something that they couldn't do before". Fred, a comedian, wanted to create positive emotions: "I create happiness, I create laughter". The participants said it was "rewarding" (Bob) and "beautiful" (Dan) when they saw their work having an impact, and it fuelled their desire to do more.

3.2.2. Learn and grow: Phrases participants used to discuss learning and growth were "developing and growing" (Jane), "reading and learning" (Bob), and "exploring" (Mark). This desire to learn created a self-reinforcing learning cycle, as Mark explained: "The more you discover, the more excited you become about it, the kind of the more things you realise that is possible, and ... the more you want to explore". Learning generated an opportunistic mindset enabling participants to spot opportunities and take up challenges to grow. This desire for ongoing development accompanied aspirations towards mastery. George emphasized "you can get better" and "be the best version of you that you can be". These reflect the desire for optimal functioning. Looking at the broader picture, we can discern interrelations between the main analytic themes: participants wanted to learn to perform at their best; performing at their best helped fulfil their authentic sense of purpose; this purpose was rewarded by the feeling they were having a positive impact. Together, these elements combine to form a passionate way of being.

3.3. Developmental factors

The key factors driving the development of a passionate way of being were feeling a sense of value and being valued, and having a sense of belonging.

3.3.1. A sense of value and being valued: One element encouraging the development of the passionate way of being was having a sense of value - both through valuing one's own actions (intrinsic satisfaction), and being valued by others for one's actions (recognition). Intrinsic satisfaction came from feeling what one was doing was valuable, as Bob expressed: "It's that it always feels like I'm doing something worthwhile". Having a sense of value was tied to participants believing in what they were doing, which again connects to following a purpose, being authentic and having a positive impact. Similarly, Anna recalls a weekly class she runs: "I just feel like I'm kind of a channel for some sort of unlocking". Anna believed she were a kind of medium, helping others to release their potential. Thus the sense of valuing one's actions was often linked to the sense one was valued by others for these actions.

3.3.2. Having a sense of belonging: Another factor encouraging the pursuit of passion was participants feeling a sense of belonging from being around likeminded individuals. Tony reminisced about how he felt in his Masters course: "That's quite powerful to be around … 60 people ... who are all thinking the same things". Lisa explained how "meeting these other inspirational women" at a personal development training group gave her the confidence to follow her sense of purpose. Some participants also created a sense of belonging for others. Dan, who runs retreats where people come for personal change, explained: "There's something about the retreat that brings people together. And... hearts open up. And people ... share, and they open up, in ways that they can't, or they won't, in their everyday lives". Dan implied something unique happens when people come together for similar objectives, and that this togetherness helps people reveal their true selves. Being a part of this change process, and creating the environment for it, helped fuel Dan's sense of belonging.

3.4. Manifestations in life

The passionate way of being manifested itself in the participants' lives in the form of the pursuit of variety, and in participants believing in their skills.

3.4.1. Pursuing variety: Most participants reported pursuing variety in their lives, from daily activities to long-term pursuits. They spoke about having a key purpose, such as "creativity and technology" (Mark), and pursuing variety around it. Dan described his purpose as "the prominent motivators", and "the passion that drives" him and that "is in charge of making choices". However, around this key purpose, participants enjoyed embracing the variety of potential outlets for this purpose. For instance, John spoke of enjoying "working with groups of people" in workshops, but appreciated being able to offer various workshop topics. This variety helped to keep the passionate way of being dynamic and continuously evolving, as Jane highlighted: "It's an extension of existing driving passions, but it's also … uncovering and creating new passions". This "creating new passions", driven by the desire to learn and grow, is one of the drivers of a passionate way of being.

3.4.2. Believing in one's skills: A second key manifestation of the passionate way of being was self-belief in one's skills. Participants had a sense of their own talents, including innate qualities and capacities they had developed over time. This self-belief meant participants had the confidence to follow their purpose and make a positive impact, as Lisa explained: "What I do know about is education. So... It meant that I could find a way to help that I was good at". Indeed, this self-belief had the potential to cause frustration among participants if they felt their skills were not being utilised. For example, Sarah recalled being in a profession which she felt did not fully utilise her potential: "If you're not in alignment with what you're there to do or how the skills you've been given can be put to best use, you're going to experience conflict". Here, Sarah was distressed and struggled to perform; this reinforced the importance of being able to do what she does best.

3.5. Passion enhancing life

Participants indicated that pursuing a passionate way of being enhanced life by leading to subjective wellbeing, feeling energised and a sense of freedom.

3.5.1. Subjective wellbeing: Participants linked their passion to experiences of subjective wellbeing by talking about happiness, positive emotions, and being satisfied with their lives. John spoke about a "very fulfilling and engaging life" driven by "I do things I enjoy doing". Tony mentioned attaining "fulfilment" and a "sense of experience" in life from pursuing this passionate way of being. Lisa highlighted how her purpose helped her focus, leading to positive emotions: "I always have my next mission ... And I think it gives me, and that's because it's driven by passions... So that definitely gives you a kind of happiness". Understanding what she was working towards gave her a sense of structure, which brought her "a kind of happiness". Other positive elements, emphasised by Anna, included being able to "connect with people" and feel "joy". In addition, connecting back to earlier themes, experiencing a sense of belonging through following her passion also contributed to her wellbeing.

3.5.2. Feeling energized: Participants described how pursuing their passion was energizing, a source of "refuel" (Sarah), "making me excited" (Tony) and generating "buzzing vitality" (Dan). Dan implied this "buzzing vitality" meant the passionate way of being was "something that sustains itself" (Dan). John explained his energy came from being "very engaged and absorbed": doing things aligned with his true self allowed him to get fully immersed in them and to enjoy them. Moreover, Fred's "childlike energy" had expansive positive effects, such as becoming "immersed in curiosity and inspiration and wonder". Here passion was a route to experiencing the world with greater vitality and awe. Finally, linking back to the earlier theme of ‘making a difference,' some participants suggested that spreading their passionate way of being to others also energised them, as Mark illustrated: "The most exciting is when when I talk to people, and then they also, they also get passionate about it".

3.5.3. Sense of freedom: Participants revealed their pursuit of passion was imbued with a sense of freedom, which arose from feeling choice and not feeling boxed in. This meant people's passion was not just limited to one activity, but could be generalised to other aspects of life. Dan expressed this clearly: "Really anything is possible. In ... many ways that's ... why I love my passion so much, because I feel that it's so flexible, and it's so open". He felt his passion opened up opportunities and conveyed the expansive feeling he was able to direct his passion in many ways, towards many activities. Sarah linked freedom to authenticity, saying she felt free when she was being authentic and pursuing the things important to her: "I come face to face with my value. I'm free". Thus, alignment with one's true self, was one of the elements that engendered a sense of freedom for respondents.

3.6. How a passionate way of being detracts from life

Although the passionate way of being was largely constructed in positive terms, the passion could have unforeseen negative outcomes. Pursuing one's passion could detract from life if it came to dominate one's life, leading to losing control, obsessing over goals and wanting to escape.

3.6.1. Losing control: Three participants spoke about the challenges they experienced when their passionate way of being became an overpowering presence in their lives. Fred expressed he was in this negative space: "I'm not empowered enough in my life at the moment to umm... Feel like I'm in control". Fully immersing himself in this way of being made him feel lost and trapped, and he was unsure how to get out. Conversely, others felt distressed when they did not have sufficient control in their life to pursue their purpose fully, a point made by Sarah above (see ‘believing in one's skills' theme). George revealed he had felt he "wasn't fulfilling what I believe was my potential" when he was doing an activity he loved, as he felt the structure he had put in place was not flexible enough. He had felt "stuck", indicating losing control and the sense of freedom.

3.6.2. Obsessing over goals: As outlined above, the passionate way of being involved following a purpose and having a positive impact. However, if these and their accompanying elements became overpowering, they could lead to goal obsession. George was vocal about this negative aspect: "To feel passionate about something, it's kind of verging on being uncomfortable about something, about being so... Verging on obsession, isn't it, it's verging on... Wanting something so much that it does hurt". That said, some participants found strategies to overcome this. Lisa described learning to stop being so goal-oriented with her passion, and appreciating it for its own sake, led her to enjoy it in a life enhancing way: "I'm understanding more that you can just do the things you enjoy and the things you love, and stop running".

3.6.3. Wanting to escape: For some participants, immersion in their passion was so all-consuming they felt the urge to escape. Fred experienced burnout from over-involvement in his passion for comedy, and did in fact escape: "I was so disillusioned and hurt… that I took an entire year off". After a year, he found himself falling back in love with comedy, understanding "it is the reality of who I am". Other participants reported the urge to escape from attendant feelings that sometimes accompanied their passion. For example, Albert spoke of how being authentic in his passionate way of being rendered him vulnerable to others' judgments: "When I've explored my passions, and talked about them openly... It... lays you vulnerable to other people's prejudices and assumptions". Exposing his authentic self made him feel uneasy about the beliefs people held about individuals like him who had the freedom and courage to shape their lives as they wanted. These external forces, others' assumptions, sometimes made him wary about pursuing his passionate way of being.

4. DISCUSSION

This study has deepened our understanding of passion by showing this to be a way of being, rather than a positive attitude towards a particular activity. Moreover, people who flourish in life as a result of finding their passion may enter a self-sustaining 'passion spiral', a new theoretical model developed by the present study (Figure 1). This study helps augment the current understanding of passion by showing how it can go beyond enthusiasm towards an activity to an actual way of life. It also provides fertile ground for future research which could further explore passion as a way of being. The four themes in this new model explain what the passionate way of being is, what it is driven by, how it develops and how it manifests itself in people's lives. Their sub-themes included following a purpose and being authentic; having a positive impact and learning and growing; feeling valued and having a sense of belonging; and pursuing variety and believing in one's skills. These components resulted in a 'passion spiral' that feeds itself, as the different components continuously reinforce each other in this cyclical process. A further two themes (right in Figure 1) demonstrated how the spiral enhanced or detracted from life. The spiral led to individuals feeling subjective wellbeing, energised and a sense of freedom. Even though relatively rare (quantitatively speaking), when the spiral became overpowering it resulted in a 'negative spiral' leading to losing control, obsessing over goals and wanting to escape. Some elements of the passionate way of being can add to our understanding of existing theories, such as Waterman's (1993) personal expressiveness, Csikszentmihalyi's (1990) autotelic personality, and Vallerand et al.'s (2003) Dualistic Model of Passion.

4.1. Passionate way of being spiral

What is unique about this model is the idea that passion is a way of being, or a quality, that the individual holds, rather than passion being a strong desire towards a specific activity (as suggested by Vallerand et al., 2003). The two key components of this way of being, following a purpose and being authentic, relate to Waterman's (1990) theory of personal expressiveness, which was influenced by Aristotle's concept of eudaimonia. Personally expressive activities are closely tied in with authenticity: individuals believe such activities are reflective of who they are and what they are meant to do (Waterman, 1990; Deci & Ryan, 2000). This description is consonant with the analysis in the current study of a passionate way of being; however, Waterman's model limits these feelings to a specific activity. In contrast, the passion model here suggests that passion runs throughout life, across different activities.

Compton et al. (1996) identified the key components of meaning as purpose, connectedness and growth. These components feature within the passion spiral in different ways. A sense of purpose is one of the two key elements of the passionate way of being (alongside authenticity); desire for learning and growth help drive the pursuit of the way of being; and a sense of belonging (i.e. connectedness) is a factor that helps it develop. This analysis ties the passionate way of being to Compton et al.'s (1996) definition of meaning. In addition, the model in the current study suggests that following one's purpose is often linked to the desire to have a positive impact, and that impacts positively on an individual's life. This introduces the idea that following a purpose and consciously creating positive impact lights up the positive passion energy within you.

The passion spiral also links conceptually to Deci and Ryan's (2000) Self-Determination Theory. The central components of this theory, relatedness, autonomy and competence, can be linked to elements in the passion spiral. Relatedness was an aspect of the spiral, since connectedness, i.e., a sense of belonging, was a key developmental factor in encouraging pursuit of the passionate way of being. Likewise, autonomy, referred to as making decisions consistent with the integral self, has parallels with authenticity (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Finally, competence is relevant to both the desire to learn as well as the belief in one's skills. With these similarities with the self-determination theory, the passion spiral suggests that this way of being allows one to enjoy self-determination, as well as other positive wellbeing outcomes, throughout their life rather than through merely one activity an individual feels enthusiasm towards.

Components of the passion spiral can also be linked to other prominent theories within positive psychology. This desire to learn can be tied to Dweck's (2006) growth mindset model, which refers to a malleable individual open to learning and challenges. Such openness to learning is clearly present in the model as the passionate way of being is driven by the desire to learn and grow. Similarly, this desire for self-expansion has parallels with Csikszentmihalyi's (1990) autotelic personality, which refers to people who generally do things for their own sake in the 'here and now', and who actively seek skill development. Establishing such links between the passion spiral and existing theories shows how the spiral fits within the context of existing understanding within positive psychology. Next we must consider how the spiral can either enhance or detract from life.

4.2. Passionate way of being and happiness

As with the philosophers' debate around the merits of passion noted above, and as per Vallerand's Dualistic Model of Passion (Vallerand et al., 2003), the passion spiral has both a bright and a dark side. The 'bright side' of the spiral - i.e., when it enhances life, producing wellbeing - can be linked to Vallerand et al's (2003) harmonious passion, which similarly has been shown to correlate with subjective wellbeing (Bonneville-Roussy et al., 2011; Philippe et al., 2009; Rousseau & Vallerand, 2008; Vallerand, 2008). Participants in the present study spoke of experiencing positive emotions (e.g. joy), fulfilment and "happiness", which aligns with what Philippe et al. (2009) found when researching harmoniously passionate people. On an eudaimonic level, following a purpose and the desire to have a positive impact, both of which are present in the passion spiral, are components of a meaningful life (Hefferon & Boniwell, 2011). This analysis and these ties to existing theories indicate that a passionate way of being encourages both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing.

However, the current study went a step further in highlighting two additional ways in which the spiral can enhance life: feeling energised; and a sense of freedom. Whereas Vallerand et al. (2003) spoke about investing energy into a passionate activity, here the passion spiral was reported as creating a feeling of energy, which could be tied to subjective vitality. Ryan and Frederick (1997) define subjective vitality as "one's conscious experience of possessing energy and aliveness" (p.530), and "having positive energy available to or within the regulatory control of one's self" (p.530). This vitality is also linked to the reported sense of freedom, as the sense of energy is manifested in the feeling that one is in control of the self and can choose to use it in any preferred way. This creation of energy also supports the self-reinforcing nature of the spiral, representing the internal 'dynamo' that sustains the spiral. The tie between passion, energy and freedom that this study suggests is the first time passion is presented as something freeing and energising. It shines light on how pursuing a passionate way of being leads to positive effects that the research around the Dualistic Model of Passion has not identified.

However, it is important to note there could also be a 'dark side' to the spiral, occurring when the passion became overpowering, thus detracting from life. One of the key factors that led to this adverse spiral was if one was dependant on external feedback in order to feel valued, instead of feeling a sense of value through intrinsic satisfaction. Another factor which pushed participants into a negative spiral was obsessing over their purpose to the detriment of allowing themselves to pursue variety. Through this they lost control of their passion, as it took over their life and they no longer had the balance that pursuing variety provided. Here we can see ties with Vallerand et al.'s (2003) obsessive passion, in which one loses control of their excitement for an activity, and obsesses over the activity and its accompanying goals. This negative outcome was also seen in Rip, Fortin and Vallerand's (2006) study on dance students, in which obsessively passionate dancers continued dancing despite injury. Similarly, two participants in the current study spoke about obsessing over their goals so desperately they became depressed. This was then associated with a sense of hopelessness, resulting in a desire to escape.

Another element which influenced whether the passion spiral was positive or negative was how challenges were approached. Even though the passionate way of being was driven by a desire to learn and grow, some participants saw some challenges as stressful situations in which they felt forced to succeed, rather than seeing them as opportunities to learn. The more adaptive latter course - being able to transform potential threats into enjoyable challenges - can be tied to an autotelic personality trait (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). This ability to transform how challenges are seen could be a key ingredient in the positive passion spiral, and needs further research. Exploring the ways in which passion can enhance or detract from life, and the factors that contribute to these varied outcomes, will be a fruitful avenue for future research.

5. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The present research had limitations which could be addressed in future research efforts. First, it could be argued that the participant sample was rather homogenous in some respects. For example, most of the participants had grown up in Western cultures and all were currently living in the Western world. Thus, future research could examine manifestations of passion cross-culturally. That said, despite a small sample size (n = 12), the participants varied in age, gender, ethnic background, educational background and choice of careers. As such, it could be argued that the passionate way of being was found across professions and demographic characteristics. Nevertheless, future work will be able to explore factors around a passionate way of being in particular sectors of the population, such as stratified by age or by socio-economic status.

Moreover, future research from a quantitative perspective could help substantiate the model further. The novelty of the model, with the view that passion is a way of being inherent in the person, helps augment the existing understanding of passion past the idea that one can only connect with passion through enthusiasm towards an activity. Future work could potentially incorporate Vallerand et al.'s (2003) Dualistic Model of Passion and its accompanying Passion Scale to explore its similarities and differences with the passion spiral. Prospective quantitative research, ideally based around a scale of the passionate way of being, will bring more generalisability to the model, of course with the proviso that the scale developed met relevant reliability and validity tests. In addition, introducing biological or neurological measures, e.g., electroencephalography to assess brain activity when talking about passion, could help explain how the passion spiral has a positive or negative effect on an individual in more detail.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The study reinforces and adds to existing findings suggesting that passion contributes to a life worth living (e.g. Philippe et al., 2009; Vallerand, 2008). The passionate way of being makes "passion" a more accessible phenomenon as it takes the specific activity out of the picture. Instead of limiting passion to a particular activity, it shows that a passionate way of being can be implemented and expressed across people's lives. It presents passion in a new light, and shows that people can pursue a varied life passionately, and that this very variety plays a crucial role in feeding the passionate way of being. The model also highlights the routes towards pursuing a passionate way of being, namely, choosing to follow a purpose and being authentic. These two elements start the self-reinforcing spiral and ensure people do not get stuck within a specific activity. These findings may be relevant to those looking to inspire passion in others, such as educators or coaches who help people to find their future direction. Identities are dynamic and continuously evolving (Schlenker, 1985), and a passionate way of being acknowledges this. Having self-awareness around one's dynamic passionate way of being minimises the risk of obsessing around a specific activity.

Finally, the passionate way of being is an answer to Lyubomirsky's critique of positive psychology interventions being a quick fix, only boosting happiness temporarily (Jarden & Steger, 2012). As passion can be seen as a way of being, and the model acknowledges people are dynamic, this life-enhancing reinforcing spiral could be a long-term solution for wellbeing. This is especially relevant because this paper's findings show the spiral results in both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing, the two components of a life worth living (Waterman, 1993). Looking ahead, the next step will be to develop an intervention which encourages this passionate way of being to come out of people on a daily basis. In sum, individuals can be encouraged to adopt a passionate way of being throughout their life. This way of being is the result of a reinforcing spiral which in turn predominantly enhances life, though in select cases can sometimes detract from it if pursued in an obsessive way. Individuals can pursue this way of being by following their sense of purpose, being authentic, and expressing their passion across different areas of their life. As such, a passionate way of being is potentially the answer to finding long-term, and self-sustaining, hedonic and eudaimonic happiness.

7. REFERENCES

Amiot, C.E., Vallerand, R.J. & Blanchard, C.M. (2006). Passion and psychological adjustment: A test of the person-environment fit hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(2), 220-229. [ Links ]

Anderson, P.F. (1986). On method in consumer research: A critical relativist perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2), 155-173. [ Links ]

Bonneville-Roussy, A., Lavigne, G.L. & Vallerand, R.J. (2011). When passion leads to excellence: the case of musicians. Psychology of Music, 39(1), 123-138. [ Links ]

Carpentier, J., Mageau, G.A. & Vallerand, R.J. (2012). Ruminations and flow: Why do people with a more harmonious passion experience higher well-being? Journal of Happiness studies, 13(3), 501-518. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2007). Grounded theory. In J. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods (2nd ed., pp. 81-110). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Compton, W.C., Smith, M.L., Cornish, K.A. & Qualls, D.L. (1996). Factor structure of mental health measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 406-413. [ Links ]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Deci, E.I. & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The "What" and "Why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. [ Links ]

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House, Inc. [ Links ]

Forest, J., Mageau, G.A., Crevier-Braud, L., Bergeron, E., Dubreuil, P. & Lavigne, G.L. (2012). Harmonious passion as an explanation of the relation between signature strengths' use and well-being at work: Test of an intervention program. Human Relations, 65(9), 1233-1252. [ Links ]

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine. [ Links ]

Hefferon, K. & Boniwell, I. (2011). Positive Psychology: Theory, Research and Applications [Kindle version]. New York, NY: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Henwood, K.L. & Pidgeon, N.F. (1992). Qualitative research and psychological theorising. British Journal of Psychology, 83(1), 97-111. [ Links ]

Jarden, A. & Steger, M. (2012). Positive Psychologists on Positive Psychology. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(2), 70-149. [ Links ]

Lafreniere, M.K., Bélanger, J.J., Sedikides, C. & Vallerand, R.J. (2011). Self-esteem and passion for activities. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 541-544. [ Links ]

Mageau, G.A., Vallerand, R.J., Charest, J., Salvy, S.J., Lacaille, N., Bouffard, T. & Koestner, R. (2009). On the development of harmonious and obsessive passion: The role of autonomy support, activity specialisation, and identification with the activity. Journal of Personality, 77(3), 601-646. [ Links ]

Mills, J., Bonner, A. & Francis, K. (2006). The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 1-10. [ Links ]

Philippe, F.L., Vallerand, R.J. & Lavigne, G. (2009). Passion does make a difference in people's lives: A look at wellbeing in passionate and non-passionate individuals. Applied Psychology: Health and wellbeing, 1(1), 3-22. [ Links ]

Pope, C., Ziebland, S. & Mays, N. (2000). Analysing qualitative data. British Medical Research, 320(7227), 114-116. [ Links ]

Rennie, D.L. (2012). Qualitative research as methodical hermeneutics. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 385-398. [ Links ]

Rip, B., Fortin, S., & Vallerand, R.J. (2006). The relationship between passion and injury in dance students. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 10(1-2), 14-20. [ Links ]

Rony, J.A. (1990). Les Passions. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Rousseau, F.L. & Vallerand, R.J. (2008). An examination of the relationships between passion and subjective wellbeing in older adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66(3), 195-211. [ Links ]

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. [ Links ]

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141-166. [ Links ]

Ryan, R.M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of wellbeing. Journal of Personality, 65(3), 529-565. [ Links ]

Seligman, M.E.P. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An Introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. [ Links ]

Schlenker, B.R. (1985). Identity and self-identification. In B.R. Schlenker (Ed.), The self and social life (pp. 65-99). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

TED (2013). Riveting talks by remarkable people, free to the world. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/. [ Links ]

Vallerand, R.J. (2008). On the psychology of passion: In search of what makes people's lives most worth living. Canadian Psychologist, 49(1), 1-13. [ Links ]

Vallerand, R.J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G.A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Leonard, M. & Gagne, M. (2003). Les Passion de l'Ame: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 756-767. [ Links ]

Vallerand, R.J., Salvy, S.J., Mageau, G.A., Elliot, A.J., Denis, P.L., Grouzet, F.M.E. & Blanchard, C. (2007). On the role of passion in performance. Journal of Personality, 75(3), 505-533. [ Links ]

Vallerand, R.J., & Verner-Filion, J. (2013). Making people's life most worth living: On the importance of passion for positive psychology. Terapia Psicologica, 31(1), 35-48. [ Links ]

Waterman, A.S. (1990). Personal expressiveness: Philosophical and psychological foundations. Journal of Mind and Behaviour, 11(1), 47-74. [ Links ]

Waterman, A.S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678-691. [ Links ]