1. Introduction

The biophysical mechanisms underlying basic experience -that being alive, whether sleeping or awake, most of the time feels like something to oneself- remain poorly understood. Some decades ago, philosopher Jaegwon Kim famously asked "[what is the] place of mind in a physical world?" (1993, p. xv). We animals, as well as every form of life, are all made from a limited set of basic molecules: nucleic acids, proteins, glycans, and lipids are the fundamental macromolecular components of all known cells (Kitadai & Maruyama, 2018; Marth, 2008). Nevertheless, arising from their limited precursors, the molecules which implement replication, compartmentalization, and metabolism came out to be incredibly diverse. As an example, with the aid of our 20000-25000 coding genes, our human cells can synthesize more than 100000 different proteins from combining merely 21 amino acids (Jiang et al., 2020; Ponomarenko et al., 2016). Just as the complexity of protein function is based on their 3D arrangements and the combination of limited basic elements, the sheer complexity of behaviors and experiences we are capable of producing and have, must have arisen from the same limited basic elements, but by means of electrical activity (Cook et al., 2014). Several research strategies to study the ‘emergence’ of consciousness have been proposed, often disagreeing about whether the correct level where to find the material constituents of consciousness is the activity of neuronal networks, computational systems, single neurons, or quantum systems (Cook, 2008).

The cellular and molecular components of cognitive and affective processes such as emotion, temperament, trauma, memory consolidation and learning, are being identified by experimental researchers with ever increasing detail (cf. Bouarab et al., 2021; Cloninger et al., 2019; Josselyn & Tonegawa, 2020). Consciousness, however, remains more elusive to this characterization. Moreover, the very study of consciousness entails a number of difficulties related to philosophical definitions and a constant revision of the mind-body problem in the light of new scientific research.

A great part of our understanding of the molecular counterparts for processes such as learning, fear response, decision making, and cognitive aging has come with the aid of pioneer model organisms such as bees, flies, sea slugs, and worms. For example, the universal molecular underpinnings of implicit memory were first discovered in the sea slug Aplysia (Kandel, 2001; Kupfermann & Kandel, 1969). Nematodes, which after exposure to the pathogenic potential of bacteria can learn to avoid them, even when they might find them attractive through taste (Zhang et al., 2005), are capable of making good decisions regarding the colony or community (Palominos et al., 2017), and can be used to study bounded rational choices (Cohen et al., 2019). The use of imaging and genetics tools is an enticing prospect if they could be applied to the study of consciousness and its disorders. However, the mere existence of consciousness in these organisms has been explicitly disregarded by some consciousness models (Barron & Klein, 2016; Bronfman et al., 2016; Mallatt, 2021). Even when our knowledge of the behavioral capabilities of nematodes -among other animals- is still incomplete, and thus there is room for reconsidering the existence of minimal consciousness in C. elegans. In the present critical review, we summarize the current models of consciousness in order to reassess, considering new evidence, whether the 302-neuron-nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, has minimal consciousness. The relevance of this resides in the apparent simplicity of the system, in which the rapid advancement of technology has provided us with genetic and molecular tools to study this model animal and its neural dynamics in a previously unthinkable resolution and detail. If C. elegans meets the criteria for consciousness set by some of the current models, then the door will open for a basic understanding of minimal consciousness from its basic mechanisms -in the sense of Bechtel (2008) or Bechtel and Abrahamsen (2013)-. In addition, the phylogeny of consciousness would need to be reconsidered.

Experience is defined by philosophers as ‘phenomenal consciousness’ (Block, 1995): if a system is capable of experiencing, then there is something that it is like to be that system, and that system is conscious (GodfreySmith, 2016; Nagel, 1974). Given the tremendous polysemy of the word ‘consciousness’, comparable perhaps to the polysemy of words like ‘cognition’ or ‘mind’, it becomes necessary to disentangle phenomenal consciousness from other flavours of the term. Phenomenal consciousness does not imply self-consciousness, or reflective consciousness. For example, "for a pain to be reflectively conscious, [. . . ] the person whose pain it is must have another state about that pain" (Block, 1995, p. 235). Therefore, phenomenal consciousness is more basic and only requires a first-person point of view (Godfrey-Smith, 2016; but see Metzinger, 2020, for an account of minimal phenomenal experience where not even a first-person point of view is required). As a property constituted by physical and biochemical mechanisms, it must have a measurable effect in the dynamic changes of the system’s parts, and the behavior of the same system has to be somewhat different in conscious and non-conscious states (Alkire et al., 2008; Lagercrantz & Changeux, 2009; Tononi & Koch, 2015). Otherwise, we would have to admit the metaphysical possibility of ‘philosophical zombies’: that two physically and behaviorally identical systems differ only in that one of them has experiences and the other does not (Chalmers, 1996). From this statement onwards, the consensus among contemporary researchers in the field stops. Given that phenomenal consciousness is an ongoing discussion, certain debates at its core remain open: some theories predict functional differences between conscious and non-conscious systems (e.g., Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2021; Mashour et al., 2020) and others do not (Oizumi et al., 2014). Some researchers assert that phenomenal consciousness does not need to have/be an adaptive function (Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2019; Hobson & Friston, 2016; Maley & Piccinini, 2018; Tononi & Koch, 2015) while other researchers argue that it does (Feinberg & Mallatt, 2016, 2018; Kolodny et al., 2021; Solms & Friston, 2018). Another disagreement is that for some researchers, phenomenal consciousness might not necessarily imply content nor its ‘synonyms’, like representations, referral, or intentionality, even though it often has content, at least for our species (Block, 1995; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2007; Hutto & Myin, 2013). However, other proposals take contents, representations, and/or intentionality to be a core feature of phenomenal consciousness (Feinberg & Mallatt, 2016; Bronfman et al., 2016). The above open philosophical debates reviewed here are by no means exhaustive, but most empirical proposals to study phenomenal consciousness can be agnostic about those more abstract debates about ‘what’ an experience (or the ability of experiencing) is, and focus on ‘how’ experience arises.

2. Frameworks for Searching the Physical Mechanisms of Consciousness

The origin of several of our impressive cognitive abilities can be tracked down the phylogenetic tree (Cisek, 2019), and consciousness should not be an exception. If we accept that we humans are conscious, and that consciousness is (albeit indirectly) an heritable trait -regardless of whether it is adaptive, neutral, slightly deleterious, an exaptation, or a pleiotropic trait- then it is quite unlikely that consciousness started with us. But without the ability of reporting their experience, other animals and pre-verbal/non-verbal humans cannot tell us whether they are conscious, so consciousness must be inferred from their overt behavior and/or the dynamics of their biochemical parts and mechanisms.

This fact makes it harder for phenomenal consciousness to be subjected to scientific examination -in comparison with access consciousness-, especially regarding its inception during phylogeny and during ontogeny. The developmental onset of basic phenomenal consciousness is yet an interesting topic to study, which sadly has been seldom covered (e.g., Lagercrantz, 2014; Lagercrantz & Changeux, 2009; Mashour & Alkire, 2013). Regarding the developmental onset of phenomenal consciousness, Lagercrantz (2014) argues that in humans it cannot precede the first thalamo-cortical connections at the 24th gestational week. This conclusion seems to stem from the thalamic dynamic core theory of phenomenal consciousness (Ward, 2011). The onset of REM sleep at 30th gestational week has been proposed as a functional keystone for the development of consciousness, for it shifts the electrical pattern of activity and prepares the developing cortex for the sensory influx at birth (Mashour & Alkire, 2013). Anticipating the more general mechanisms underlying the onset of phenomenal consciousness in a minimal organism, recent studies with human brain patterned "cortical" organoids exhibit progressive increases in local field potential recordings, as well as nested oscillatory waves. Phenomenal consciousnes may appear when the network starts to show prolongued spreading activity in response to perturbations, which, due to a combination of technical and important ethical reasons, remains yet to be tested both in human brain organoids or in other animals (Jeziorski et al., 2022).

A less rocky research avenue stems from the knowledge of that there are some scenarios where consciousness is lost in our species: coma and vegetative states (Laureys et al., 2004; Plum et al., 1998; Sitt et al., 2014), some types of general anesthesia (Alkire et al., 2008; Bola et al., 2018; Bonhomme et al., 2019; Hudetz & Mashour, 2016; Mashour & Alkire, 2013), and during generalized seizures (Arthuis et al., 2009). It can also be severely distorted: hallucinogen drugs (Bayne & Carter, 2018; Stiefel et al., 2014), and dreamless sleep (Darracq et al., 2018; Siclari et al., 2017).

Thus, a first strategy is to track dynamical changes accompanying the loss of consciousness: what it is lost and what appears anew when we transit between conscious and non-conscious states. For example, in human EEG parietal cortical recordings, after a transcranial magnetic stimulation delivered to medial superior parietal cortex, the gamma band activity (30-45 Hz) is higher for wake and disconnected (e.g., ketamine anesthesia, REM sleep) conscious subjects than for unconscious (e.g., propofol anesthesia, deep sleep) subjects (Darracq et al., 2018). However, excessive coupling in the gamma band activity indicates loss of consciousness during NREM sleep and propofol anesthesia both in humans and macaques (Bola et al., 2018). This can be generalized to other animals by asking whether the behavior, neural and/or molecular dynamics of an animal from another species under coma, general anesthesia, hallucinogens, seizure, or dreamless sleep, match our behavior, neural and/or molecular, during those states.

Following this strategy, several different minimal functional requisites for a system to be conscious have been proposed in the last years. For example, Global Workspace Theory (GWT) states that a long-range network of cells connecting several local (modular) networks broadcasts information, making it globally available to the whole network (Dehaene et al., 2011; Mashour et al., 2020). At its most abstract level, GWT’s requires the activity of a long-range neuronal network which mobilizes or inhibits the contribution of processing (perceptual, motor, evaluative, and memory) neuronal networks through descending connections (Mashour et al., 2020). The theory deals with awareness of specific stimuli being broadcasted by ignition, a sudden non-linear dynamic neural pattern, which operates as a threshold of conscious perception. GWT gathers a lot of evidence from masking and inattention paradigms, where some stimuli are not consciously processed (Dehaene et al., 2006; del Cul et al., 2007). In humans, a cortico-cortical frontoparietal recurrent network, which also recruits subcortically thalamic and cerebellar nuclei neurons, seems to implement the Global Network Workspace, attention, and working memory (Mashour et al., 2020). Also, its functional connectivity gets impaired under propofol, sevoflurane or ketamine anesthesia (Hudetz & Mashour, 2016). This theory follows a distinction between phenomenal and access consciousness (Block, 1995), in which the first, the one we address here, involves subjective experience, and the latter (addressed by GWT) involves accessibility of information to numerous cognitive modular processors. Yet, Carruthers (2018) even argued that if GWT provides a complete account for human phenomenal consciousness -in addition to characterizing its target: access consciousness-, then "there is no fact of the matter whether nonhuman animals are phenomenally conscious" (Carruthers, 2018, p. 48). Regarding empirical research, GWT is a framework mostly explored in humans, but, in disagreement with Carruthers (2018), there are few works assessing a global network workspace in other animals, mainly vertebrates. For example, there is evidence of ignition in carrion crow’s nidopallium caudolaterale area when a sensory representation becomes an explicit working memory state (Nieder et al., 2020). Similar evidence has been found in other primates (Panagiotaropoulos et al., 2012; van Vugt et al., 2018).

A second strategy is to search what structures are needed to show consciousness. Here we find molecular, cellular, anatomical, and architectural approaches; all of them can also be generalized to search consciousness in other animals.

For example, Integrated Information Theory (IIT 3.0) postulates an axiomatized model of consciousness, starting from a set of axioms and attributing conscious experience to an irreducible repertoire of cause-effect mechanisms within a system. How irreducible this repertoire is, compared to its minimum information, is measured by ϕ, the integrated conceptual information. A physical mechanism, like the activity of a nervous system, is conscious if its maximum value of ϕ is > 0 (Oizumi et al., 2014; Tononi et al., 2016; Tononi & Koch, 2015). Within IIT, two functionally equivalent systems (i.e., where both produce the same input-output behavior in time) can differ in their consciousness depending on their architecture. For example, a feedforward system has always ϕ = 0, while a feedback system with recurrent connections has ϕ > 0 (Oizumi et al., 2014). ϕ is hard to measure for very large systems due to computational demands, thus, usually only surrogates of ϕ are calculated (Barrett & Seth, 2011; Kim et al., 2018), showing that, in humans, information integration collapses in some states like midazolam-induced anesthesia (Ferrarelli et al., 2010), and in early slow wave sleep, but recovers in REM-sleep (Massimini et al., 2005). Regarding consciousness in other animals, although few attempts to measure ϕ -or related coefficients- have been made (e.g., Antonopoulos et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2021; Oizumi et al., 2016), their phylogenetic scope is wider than the GWT. For example, it has been shown that the integrated informational structure of a set of ϕ values, used as a proxy for ϕ, collapses during isoflurane anesthesia in Drosophila melanogaster, possibly signaling loss of consciousness (Leung et al., 2021).

The disagreement between frameworks persists, but each consciousness model can be used to track one or more evolutionary origins of phenomenal consciousness. Searching for their requisites across the phylogenetic tree is something that a few consciousness researchers have already attempted to do (Bronfman et al., 2016; Cabanac et al., 2009; Feinberg & Mallatt, 2016; GodfreySmith, 2016; Mashour & Alkire, 2013).

Neurobiological naturalism (Feinberg, 2012; Feinberg & Mallatt, 2016, 2018; Mallatt, 2021) proposes that consciousness emerged from evolutionary steps in living systems. First of all, embodiment entails a separation between a system and its surroundings (e.g., a membrane for unicellular organisms), which allows the possibility of a first-person or subjective point of view. Then, the centralization of nervous nets into ganglions and brains allowed the fast coordination of large multicellular bodies. The increasing complexity of the networks yields the integration of central pattern generators for rhythmic activities such as digestion or locomotion, homeostaticdriven simple and complex reflexes, and sensorimotor loops. They argue that consciousness appears when brains have many neurons of many subtypes and with reciprocal recurrent connections; elaborated sensory organs able to topographically map the external world and/or bodily structures; and neural hierarchies codifying valence through neuromodulation. This promotes both arousal, selective attention, and working memory, the latter being needed for the continuity of experience in time. Given this set of requisites, Feinberg and Mallatt (2016, 2018) propose that consciousness may have arisen 560-520 million years ago, and is present in at least vertebrates, arthropods, and cephalopod mollusks. Notwithstanding, no clear markers nor quantitative substantiated criteria to distinguish conscious from nonconscious systems are formulated in Feinberg and Mallat’s account, as only a checklist is presented.

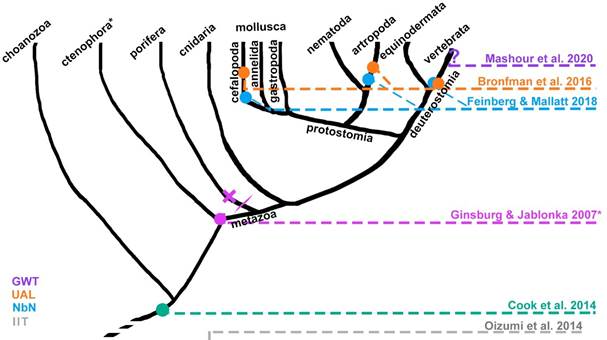

Finally, the Unlimited Associative Learning (UAL) framework combines both previously outlined strategies. It proposes that minimal (phenomenal) consciousness can be tracked down the phylogenetic tree by looking for an evolutionary transition marker, a single capacity enabled by a system which has completed the transition in question from non-conscious to conscious. Ginsburg and Jablonka (2019, 2021) argue that systems with limited associative learning (LAL) are able to combine simple reflexes with stochastic exploratory behavior, and such combinations can be reinforced or punished with rewards or aversive consequences, while both unconditioned stimuli and conditioning stimuli are simultaneous. When there is a delay between them, such as in trace conditioning paradigm, the organism is unable to learn (Birch et al., 2020; Bronfman et al., 2016; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2019, 2021). In contrast, an animal shows UAL if: (i) it can learn configurally, i.e., if it can distinguish a multimodal pattern like an apple from the sum of features composing it, like the visual stimuli, the volatile organic compounds emanating from it, the texture, etc. This requires both multimodal binding of stimuli and pattern completion/separation, thus the conditioning stimuli or the reinforced action pattern can be complex and learned as a whole. (ii) It can learn cumulatively (second order conditioning), which indicates a flexible value system. And (iii) escape from immediacy: the ability to learn associations when they are temporally disjoint, such as in trace conditioning (Bronfman et al., 2016; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2021). Ginsburg and Jablonka (2021) propose that UAL was one factor driving the animal diversification of the Cambrian explosion (541-530 million years ago). All animals which conclusively show associative learning have a brain, thus a brain seems to be a necessary (not sufficient) condition for LAL and UAL (Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2019, 2021). The evolution of brains is closely linked to the evolution of bilateral symmetry, and a further differentiation between sensory and motor regions (both dorsoventral and cephalocaudal differentiation), intertwined with further specialization and modularization of the nerve net into sensory-motor integrative units, improves the ability of changing direction fast in response of the evaluation of sensory information (Arendt et al., 2016; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2021; Holló & Novák, 2012). The minimal functional architecture necessary to enable UAL requires bidirectional connections between a world-learning circuit and a self-learning circuit, each one composed by receptor cells, sensory units, sensory integration units, connected through sensory-motor association units, and memory units to motor integration units, central pattern generators, and motor units. Association units are also connected to reinforcement units afferentiated by receptor cells and sensory units (Bronfman et al., 2016). The UAL framework claims that at least most vertebrates, some arthropods, and the coleoid cephalopods are minimally conscious (Birch et al., 2020). It is necessary to remark that UAL is proposed as a positive marker: it can only show which animals are conscious, but for an animal to lack UAL does not mean that it lacks some form of minimal consciousness (Birch et al., 2020). The phylogenetic hypotheses of some of the major consciousness frameworks are summarized in Figure 1.

3. C. Elegans as a Model for Phenomenal Consciousness?

Caenorhabditis elegans is a free-living nematode found predominantly in humid temperate areas with a lifespan of about three weeks. In alternative developmental states, like during hibernation triggered by harsh environmental conditions, its lifespan is extended to 3 months (Ewald et al., 2017; Frézal & Félix, 2015). C. elegans reproduces by self-fertilization or by mating with males (Frézal & Félix, 2015). Nematodes have been around for the last 1000-400 million years (Vanfleteren et al., 1994), and the C. elegans supergroup diverged from other Caenorhabditis groups 30-5 million years ago (Frézal & Félix, 2015). The adult C. elegans hermaphrodite has 302 neurons, 8000 chemical synapses, 1410 neuromuscular junctions, and 890 gap junctions; the neurons act on 132 muscle cells; whereas male C. elegans has 385 neurons, 155 muscle cells and slightly more connections than its hermaphrodite counterpart (Cook et al., 2019; White et al., 1986; Witvliet et al., 2021). The 302 neurons can be classified into 118 anatomically distinct classes, but molecular classification suggests more subtypes (Cook et al., 2019; Hobert et al., 2016).

It is well established that C. elegans is capable of non-associative learning, showing habituation or sensitization to stimuli like gentle touch and non-pathogenic smells (Chalfie & Sulston, 1981; Rankin et al., 1990; Rose & Rankin, 2001). The worm also performs associative learning (Ardiel & Rankin, 2010; Sneddon, 2018), and long-range memory formation that transcends generations (Moore et al., 2019; Palominos et al., 2017; Pereira et al., 2020). C. elegans has high-threshold mechanoreceptors (Albeg et al., 2011), heat thermoreceptors (Beverly et al., 2011), and chemoreceptors (Bargmann, 2006). Regarding the difference between nociception and pain, C. elegans has an endogenous opioid system with components closely related to the mammalian one (Cheong et al., 2015; Sneddon, 2018). Opioid neuromodulation in humans and other animals can result in altered conscious states (Stiefel et al., 2014), and -as far as we know- is absent in clades such as Cnidaria or Annelids (Sneddon, 2018). Additionally, C. elegans can integrate stimuli through globally coordinated dynamic oscillatory activity, and internally represent motor action plans (Kato et al., 2015).

The centralized and plastic nervous system of C. elegans is able to integrate input from thermoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, and nociceptors (Ghosh et al., 2016, 2017; Harris et al., 2019; Ishihara et al., 2002; Metaxakis et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2022). This integration is achieved at the network level (Metaxakis et al., 2018) or even at the single neuron level: some C. elegans’ neurons are polymodal (Goodman & Sengupta, 2019; Ji et al., 2021). Despite its ability to perform non-associative and associative learning -which imply the expression of long-term memory consolidation genes, even after vitrification (Lakhina et al., 2015; Vita-More & Barranco, 2015)-, Barron and Klein (2016) argue that its responses are bounded to immediate environmental or interoceptive signals. C. elegans is unable to perform directed hunting but rather increase its locomotion randomly when hungry (Klein et al., 2017). For Barron and Klein (2016), the difference between conscious arthropods or vertebrates, and C. elegans, is that the former’s goal directed behavior is organized in response to an integrated simulation of their environment and their body. In contrast, they argue that C. elegans lacks the spatial memory necessary to model its environment.

Note. UAL corresponds to Bronfman et al. (2016), and a previous version to Ginsburg and Jablonka (2007). Neurobiological naturalism (NbN) corresponds to Feinberg and Mallatt (2018), and IIT -which goes beyond living organisms- to Oizumi et al. (2014). GWT (Mashour et al., 2020) is represented with a question mark because as far as the authors know, they have not explicitly pronounced about the phylogenetic roots of the global workspace. Cook et al. (2014) marks the origin of sentience in unicellular protozoa. *Ctenophora was recently classified as the sister group of all animals, but as the debate persists, it isn’t yet clear whether if phenomenal consciousness is indeed present in both cnidaria and ctenophora, it would be due to an early origin and a secondary loss in the porifera clade, or due to two unrelated origins.

Figure 1 Simplified Genealogy of Phenomenal Consciousness according to Different Frameworks

Mallatt et al. (2021) go further and compare C. elegans patterned search for bacterial food with the plant’s circumnutation or growth movement, arguing that both plants and C. elegans behavior is goal-directed and persistent, yet nonconscious, due to not being directed by specific neural representations of the world, or the past. Bronfman et al. (2016) argues that without evidence of C. elegans being able to learn non-elementally (i.e., configurally) and due to its inability to learn in trace conditioning paradigms (Bhatla, 2014), we might conclude that C. elegans lacks UAL, and thus, a clear consciousness marker. We must remember, however, that UAL deliberately sets a high bar for consciousness as acknowledged by its proponents (Birch et al., 2020).

Each one of the previous arguments seems to assume that minimal consciousness must serve a specific function -which might be granting the system global accessibility to neural representations of the environment, its body, or the past-, thus conflating phenomenal consciousness with access consciousness. Surely those criteria would be sufficient to show that the animal in question is conscious, but they also might be setting the bar too high (Birch et al., 2020). How can we make testable predictions of what a ‘simple’ system needs to show in terms of neural dynamics, behavior, structural, and functional connectivity to suggest that it is phenomenally conscious?

4. Unlimited Associative Learning as an Evolutionary Transition Marker of Consciousness

The UAL framework opens the opportunity to consider several behavioral, cognitive, phenomenological, and neural hallmarks of consciousness drawn from most competing frameworks. What is particular of UAL is the way it connects them both as requisites for phenomenal consciousness and for enabling the associative learning features that are sufficient for animals to learn about the world and themselves in an open-ended way (Birch et al. 2020). See Table 1 for a summary.

4.1 Evidence of Global States in C. Elegans

C. elegans’ undulatory gait requires the coordination of muscles according to the properties of the medium through which it is moving (for example, crawling in a gel vs. swimming in a more liquid environment). In forward locomotion, this is achieved either by a chain of reflexes, generating bending waves through the worm’s body, implemented by cholinergic-driven proprioceptive feedback loops between VB and DB motoneurons (Wen et al., 2012), or by a central pattern generator (CPG) composed of one or more neurons in the ventral nerve cord (Olivares et al., 2018; Webb & Kato, 2022). This implies that there is a cluster of coordinated global control of motor activity in the C. elegans nervous system, which along multisensory integration (Metaxakis et al., 2018) can yield differentiated global states which promote associative learning.

In addition, C. elegans is capable of entering a developmentally-timed lethargus which lasts 2 hours at the end of each larval stage, and a stress-induced quiescence state, both of which have been described as sleep-like. Given that they fulfill all behavioral criteria of sleep, which are: a reversible quiescent behavior, increased arousal threshold, a stereotypical posture, and homeostatic rebound in the case of developmentally-timed sleep, some researchers argue that both are bona fide sleep states (Lawler et al., 2021; Nichols et al., 2017; Trojanowski & Raizen, 2016). Also, C. elegans can undergo an alternative larval development, the dauer larvae, due to starvation, which triggers a biphasic behavioral response consisting in increased physical activity and suppressed sleep followed by decreased physical activity and increased sleep (Wu et al., 2018). During sleep, 75% of C. elegans’ neurons displaying activity during wakefulness become inactive, thus configuring a different global neural state (Nichols et al., 2017). Besides, adult C. elegans response to noxious stimuli becomes delayed due to modulation of premotor neurons, and the chemosensory neurons’ response in presence of appetitive stimuli is prolonged (Lawler et al., 2021). Although being unresponsive to propofol, the anesthetic with more evidence in inducing unconsciousness in humans (Forman, 2006), C. elegans responds to volatile ketamine and isoflurane in an agent and concentration-dependent manner, such as it occurs in vertebrates (Nambyiah & Brown, 2021). Whether its neural dynamics are also globally different when under sleep and/or anesthesia is yet to be researched empirically. Could C. elegans have different experiences during different global states?

4.2 Evidence of phi (ϕ) and Integration over Time in C. Elegans

Regardless of not being considered by Birch et al. (2020) among their hallmarks of consciousness, ϕ allows to quantify the amount of information contained in the interaction among parts of a system and not within the parts themselves (Luppi et al., 2021). Mallatt (2021) argues that with only 302 nodes and assuming only 2 possible states per node, calculating the Transition Probability Matrix for the C. elegans nervous system gives us 8.148 109 possible states, which goes beyond existing computational power and makes the measurement of ϕ in a biophysical model of the worm, taking into account its full connectome as practically impossible. To overcome this difficulty, Antonopoulos et al. (2016) built a simplified model of C. elegans neural dynamics, performing community detection algorithms to localize densely connected subgraphs of the 277-neuron somatic nervous system of the nematode C. elegans and reducing it to a 6-node network. Then, they simulated neural dynamics for the resulting network using identical Hindmarsh-Rose neurons, and calculated auto-regressive integrated information (ϕ AR ) as a proxy of ϕ. They concluded that the brain dynamic neuron model has a positive ϕ AR , and thus generates more information than its constituent parts alone. This is coherent with findings about C. elegans functional connectivity, which show that instead of a feedforward linear on/off circuit, its sensorimotor neural architecture is distributed, oscillatory, and highly interconnected through feedback between nodes (Kaplan et al., 2018).

4.3 Evidence of a Flexible Evaluative System in C. Elegans

Being able to change the valence associated with contexts or stimuli is associated with pleasure, displeasure, and affect. To do so seems to require second order conditioning -to associate novel neutral stimuli with previous conditioned stimuli- and reversal learning -to suppress a behavior associated with a previously rewarding or aversive conditioned stimulus, when the stimulus becomes associated with a threat or a reward, respectively- (Birch et al., 2020). Strict and arbitrary long-term reversal learning has not been shown in C. elegans so far, but it can learn both appetitive and aversive new relationships (Amano & Maruyama, 2011; Ardiel & Rankin, 2010; Nishijima & Maruyama, 2017). Stimuli can change valence for C. elegans in relation to whether it is hungry or fed (Davis et al., 2017), and it can show context condi tioning and blocking conditioning, which are second order paradigms (Merritt et al., 2019). Most importantly, C. elegans can transiently change its behavior towards NaCl concentration gradients from attraction to strong repulsion when a NaCl(aq) gradient is presented to a naïve C. elegans in absence of food (bacteria) for 15 minutes or longer (Hukema et al., 2008). This gustatory plasticity phenomenon is reversible (repulsion lasts less than 5 minutes) and depends on the sensitization and adaptation of three neurons in particular (ASEL, ASER, and ASH), possibly due to the signaling of one or more intermediate neurons (Dekkers et al., 2021). C. elegans can also alternate between attraction and repulsion to CO2 depending on its recent experience with CO2 (Guillermin et al., 2017); notwithstanding, the valence flexibility shown towards CO2 does not necessarily imply that C. elegans is able to learn delay or trace conditioning paradigms with CO2 as a conditioning stimulus (cf. Bhatla, 2014). The relationship between valence and integration in C. elegans has also been studied: depending on concentration of the aversive molecules, it can cross an aversive Cu2+ barrier or a hyperosmotic barrier if a gradient of a volatile attractant is present (Ghosh et al., 2016; Ishihara et al., 2002). The decision can be modulated by internal states of the worm like hunger/food deprivation, in a top-down manner (tyraminergic neuromodulation) and in a longer timescale (Ghosh et al., 2016). Finally, C. elegans is able to modify its spatial pattern preference, which is tuned by naturally occurring variations in the mechanosensory channel TRP-4 and the dopamine receptor DOP-3, due to previous experience and starvation (Han et al., 2017). On the other hand, there is no evidence of emotional reactions, perdurable changes in stimuli valence, nor complexaction selection in C. elegans.

Table 1 Summary of the Current Evidence of the Criteria Reviewed in the Literature for Experiencing (Phenomenal Consciousness) in C. Elegans

| Criteria | Found in C. elegans | References |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiated states and global activity | Yes. C. elegans forward and backward gaits are generated by either a reflex chain, or one or more CPG’s. Also, pirouettes and other motor commands require reverberating collective nested neural dynamics. Finally, it is argued that C. elegans have true sleep states, and its behavior changes globally under some anesthetics. | Wen et al., 2012; Olivares et al., 2018; Kato et al., 2015; Kaplan et al., 2020; Trojanowski & Raizen, 2016; Nichols et al., 2017; Nambyiah & Brown, 2021 |

| Binding and integration | Yes. There is evidence for multisensory (chemical, mechanical and thermal) integration. Also, several sensory neurons in C. elegans are polymodal. Finally, a computational model of C. elegans’ neural activity show positive values of Phi (ϕ) | Ghosh et al., 2017; Metaxakis et al., 2018; Goodman & Sengupta, 2019; Antonopoulos et al., 2016 |

| Flexible evaluative system | Perhaps. C. elegans is capable of non-associative and associative learning, and of integrating cues with opposing value in order to make a decision. There is some evidence of experience-dependent preferences, gustatory plasticity, and second order learning. | Ardiel & Rankin, 2010; Ghosh et al., 2017; Guillermin et al., 2017; Dekkers et al., 2021; Merritt et al., 2019 |

| Embodiment and self | Perhaps. There is an efferent copy of motor commands. Communication with bacteria promotes intergenerational memories depending on the bacterium’s virulence. Induction of diapause is pheromone-dependent and thus, C. elegans can recognize its community. | Ji et al., 2021; Palominos et al., 2017; Gabaldon & Calixto, 2019 |

| Intentionality | Not known. Mapping of worldly objects or C. elegans’ own body in neuronal networks seems limited, and goaloriented behavior doesn’t seem to be informed by internal states decoupled from the immediate environment. | |

| Selective attention | Not known. |

4.4 Evidence of Proprioceptive and Worldly Mapping in C. Elegans

Navigation, reversal, egg-laying, feeding, and defecation in C. elegans are composed by brief motor motifs such as limb movements organized sequentially by globally distributed, continuous, and low-dimensional neural dynamics. For example, the pirouette, an action sequence consisting of a movement forward, a reversal, a ventral turn, and then forward again, has a specific neural dynamic. The neural dynamics persists even when a hub premotor neuron is acutely silenced and thus, when the dynamics are decoupled from the motor output, the motor command is a result of collective dynamics, and its represented neurally in a way that it can be detached of the actual movement (Kato et al., 2015). Furthermore, C. elegans shows three hierarchies of nested dynamics at different timescales, controlling motor neurons patterns through proprioceptive feedback (Kaplan et al., 2020).

Proprioception also plays a role in sensorimotor integration: a rudimentary self-model is implemented via a type of motor-sensory feedback called corollary discharge (also known as efferent copy of the outgoing motor command) which cancels sensory reafferents caused by self-motion. In C. elegans, the AIY neurons encode temperature changes in a locomotory state-dependent manner (Ji et al., 2021). Yet, it is not known whether a C. elegans’ efferent copy can inhibit conditioned pathways, which according to Ginsburg and Jablonka (2019) is needed in order to have LAL.

Intentionality, in the philosophical jargon implies for an experience to be about something: someone’s desire for sushi is about sushi, but sushi itself is not about anything; in contrast, intention, which is a related but different term, implies goal-directedness (Searle, 1979). Feinberg and Mallatt (2016, 2018) link intentionality (referral) with a hierarchical topographical mapping of the world and the body (somatotopy), necessary for consciousness; and intention (teleonomy) with a goal-directed process evolved by natural selection and, thus, a general feature of life. Therefore, Mallatt et al. (2021) argue that truly proactive behavior, such as finding a goal in absence of a sensory trail, indicates consciousness, for it implies a neural map of the environment. The exploratory search displayed by C. elegans when it encounters a new environment is rather close to a biased random walk, consisting in forward crawling (runs) and head swings, which enables it to pick a new forward orientation (turns). The combined pattern of runs and turns can be modeled as diffusive movement at long time scales, even in thermal or chemical (food) gradients. The same strategy of exploratory searching can be observed in a Drosophila larva (Klein et al., 2017). The UAL framework (Bronfman et al., 2016; Birch et al., 2020; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2021) identifies arthropods, such as Drosophila, as conscious, and so does Feinberg and Mallatt (2016, 2018, 2020). Thus, are Drosophila larvae not conscious yet? Or is (memory based) proactive movement not a truly necessary condition to be conscious? Given that UAL is presented as a positive transition marker (Birch et al., 2020), the abandonment or loosening of this hallmark might not be problematic for determining whether C. elegans are conscious or not, but, if memory based proactive movement ends up being necessary for UAL -which has to be determined empirically-, this could mean that UAL might not be an optimal transition marker for the emergence of minimal consciousness, and a more basic one is yet to be suggested.

4.5 Evidence of Registration of Self-Other in C. Elegans

Besides the aforementioned efferent copy, necessary to distinguish between oneself and the environment (Ji et al., 2021), the reciprocal and specific communication with "another" requires a sense of one’s identity and that of others in the vicinity. In C. elegans, intraspecific communication and recognition is achieved through several distinct pheromones (McGrath & Ruvinsky, 2019). In particular, relationships or interactions that ought to be remembered hold evidence that the identity of the other, conspecific or not, has left a trace. Some of these memories are relevant enough to be passed to the next generations and inherited transgenerationally. Such is the communication between C. elegans and microbial pathogens, or the experience of stressful environmental changes. For example, C. elegans avoids feeding on Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14, a virulent bacteria that causes disease to the worm (Zhang et al., 2005), and chooses an alternative source of food. However, if the pathogen is of moderate virulence, C. elegans requires two generations to mount an avoidance response. In this scenario, a percentage of the population is committed to enter diapause as an avoidance strategy (Palominos et al., 2017), ensuring the survival of the community for as long as animals are in hibernation while exposed to the pathogen. Both avoidance and diapause formation are transgenerationally inherited to the progenies (Gabaldón et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2019; Palominos et al., 2017; Pereira et al., 2020). These strategies are based on the community and require a minimal critical mass, which is sensed through pheromones (Golden & Riddle, 1984). While all animals undergo transcriptional changes to respond to the pathogens (Gabaldon et al., 2019), only a fraction of the population is committed to diapause with a constant number throughout the generations and experimental interventions. Even dead individuals are perceived as "community" members, likely because the pheromones can still be sensed by others (Gabaldon & Calixto, 2019).

Birch et al. (2020) suggest that the evolution of mechanisms restricting the transgenerational transmission of the effects of stress to the next generation took place after the Cambrian explosion, and thus, transgenerational transmission of the effects of stress are more likely in animals without UAL than in animals showing UAL. Thus, Birch et al. (2020) expect that planarians and nematodes would have more widespread epigenetic inheritance than Cambrian’ latecomers, and, therefore, be less likely to be conscious. Nevertheless, genes erasing epigenetic stress methylation states, such as DDM1 or Lsh, are conserved from plants to mammals (Iwasaki & Paszkowski, 2014; Tao et al., 2011), and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in vertebrates, specially when it is mediated bysmall non coding RNAs (i.e., siRNAs, miRNAs, piRNAs, tsRNAs, rRNAs, and circRNA), is only beginning to be unraveled (Bowers & Yehuda, 2016; Hime et al., 2021; Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018; Zhang & Tian, 2022). Therefore, regardless of Birch et al. (2020) claim, the augmented prevalence of epigenetic inheritance in animals without UAL (and thus, without consciousness) remains conjectural.

4.6 Functional Remarks: Global Broadcasting, Intentionality, and Access Consciousness in C. Elegans

As far as we know, the phenomenon of ignition -capable of making incoming information globally available- has not been observed in C. elegans. It can be argued, nevertheless, that animals without the machinery to broadcast global exteroceptive or interoceptive states, and which lack a topographical map of their body as well as the environment, and also lack representations/intentional objects, can still be conscious (Godfrey-Smith, 2016). Conscious of what? It can be something raw, such as the Ginsburg and Jablonka’s (2007) ‘white-noise sensation’ analogy in cnidaria, where the persistent and recurrent stimulation of two-way signaling nerve nets might have an ‘overall sensation’ byproduct, which spans from interconnected reflex circuits, but does not inform the animal about anything of its body nor of its environment. Or, as Lacalli puts it, animals lacking an evolved central nervous system might nevertheless "experience a buzz of random real-time noise" (2020, p. 7). In a less speculative vein, other researchers talk about endogenous feelings like thirst, hunger, shortness of breath, or pain, as being nonintentional, i.e., purely phenomenal, (Brandom, 1994; Metzinger, 2020; Rorty, 1979) and prior to representational phenomenal consciousness (Godfrey-Smith, 2016; Kolodny et al., 2021; Solms & Friston, 2018). Thus, intentionality understood as aboutness or referral directed at something represented by the (neural) activity of the system might not be needed for phenomenal consciousness. There is a much more basic sense of intentionality that some philosophers assert that is either constitutive of phenomenal consciousness (Zahavi, 2003) or grounded by phenomenal consciousness (Pautz, 2013). This ‘phenomenal intentionality’ is not representational and might be possessed by any phenomenally conscious system, regardless of their neural ability to form compound stimuli, to categorize, or to hold complex integrated memories of objects in their working memory (or long-term memory) mechanisms. Thus, phenomenal consciousness can be researched empirically without conflating it with access consciousness. Some already existing empirical conceptualizations of that kind of basic phenomenal consciousness are integrated information in a system (Oizumi et al., 2014; Tononi & Koch, 2015; Tononi et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2021) and tonic alertness (Metzinger, 2020). There is, for example, evidence of pain felt -which differentiates from mere nociception in that pain must be non-reflexive and imply awareness (Elwood, 2019)- in several animals which would not pass GWT criteria of consciousness, such as chickens, zebra fishes, or hermit crabs (Godfrey-Smith, 2016), showing that working memory is not required for experiencing pain. On the other hand, insects, which pass the criteria for consciousness in some frameworks (Barron & Klein, 2016; Bronfman et al., 2016; Feinberg & Mallatt, 2016, 2018), and have working memory mechanisms (Kuntz et al., 2017; Nityananda, 2016), do not show evidence of pain so far (Eisemann et al., 1984; Godfrey-Smith, 2016; Groening et al., 2017); nevertheless, for tentative results against that consensus, see Gibbons et al., (2022). This opens the possibility of at least basic consciousness without a global workspace network and even without pain responses. Also, there is growing evidence of the dissociability of attention and consciousness: recent research suggests that attention can operate on stimuli that remain outside consciousness, and, more controversially, that attention might not be necessary for consciousness (Maier & Tsuchiya, 2021).

5. Empirical and Computational Approaches to Worm Consciousness

Even if C. elegans does not match all the criteria set by the literature, there are promising paths to further study whether it has phenomenal consciousness and how it may depend on different global states such as sleep/wakefulness, diapause, anesthesia, etc. Here we outline some approaches:

The feedback distributed architecture of C. elegans nervous system results promising for measuring ϕ within the system. Current live imaging techniques allow the simultaneous measurement of the activity of tens or hundreds of neurons while the animal performs behaviors (Kato et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2017; Randi & Leifer, 2020), and thus a growing repository of data exists that can be characterized with statistical tools. The dimensionality of this data is still huge, but eventually the problem of calculating ϕ (or some of its proxies) will be tackled. It would be also interesting to compare measures of ϕ during wakefulness, developmentally-timed sleep, and stress-induced sleep, and/or during isoflurane or ketamine anesthesia to see whether it collapses. The advancing technical developments alongside the ‘simplicity’ of its nervous system makes it an excellent model to study the onset of phenomenal consciousness during development, from proliferation and organogenesis to the four larval stages and beyond, by measuring ϕ in selected time windows. Furthermore, the door will be open to employ a battery of genetic tools to test different hypotheses about consciousness.

Relevant behavioral tests for the study of consciousness, such as reversal or trace conditioning, can be implemented with more ecologically relevant stimuli, in order to search for more complex forms of valence flexibility and an analogue of working memory. For example, well established paradigms of threat recognition, such as the response to pathogens, can be employed as unconditioned stimuli. It would be interesting to have calcium or electrophysiological recordings of the worms solving those behavioral tests.

Building a biophysically inspired computational model of the structural and functional connectome of C. elegans, taking into account what we now know of its circuits, and its neuronal dynamics and kinetics (Cook et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018; Nicoletti et al., 2019; Witvliet et al., 2021) might allow us to accurately measure complexity and consciousness through ϕ, and at the same time characterize different complexity-related indexes like synergy, long term dependencies, etc. Many existing models approach the generation of behaviors or movements in the animal (see Izquierdo, 2019, or Randi & Leifer, 2020, for a review) and they can be analyzed by themselves or be integrated in a progressively bigger and more comprehensive type of models such as the c302 modeling framework from the OpenWorm project (Gleeson et al., 2018), or the multilayered connectome, which encompasses the different kinds of modulation present in C. elegans (Bentley et al., 2016).

The advancement of transcriptomics, resulting in mRNA profiles of sleeping and waking in the nervous system of several species (e.g., Bellesi et al., 2015), may as well complement the behavioral strategies, and the information theory derived measurements. Just as immediate early genes can signal learning and memory, dynamic gene expression maps may be used to characterize variations in phenomenal consciousness. Yet, the current viability of that approach remains speculative.

As complexity arises, and in a similar manner to the experimental recordings, clever statistical tools will have to be employed to obtain a robust characterization. Also, it will be critical to contrast the model with empirical evidence to assess its biological plausibility as well as its capacity to reproduce the data.

Finally, having a tentative answer regarding C. elegans consciousness can improve our phylogenetic insights and hypotheses about the origins and possible general mechanisms of basic phenomenal consciousness, and also allow us to empirically assess both philosophical problems (such as the possibility of behaving zombies by means of selective ablation of neurons, for example) and biomedical problems regarding diseases and drugs capable of affecting consciousness in our species.