INTRODUCTION

The proper management of liming and fertilization is almost an imposition for fruit trees grown in sustainable systems and with high productivity, since it is necessary to supply the nutritional demand of the plants and to compensate the poverty of tropical soils due to the large amounts of nutrients immobilized by the vegetation or exported by each crop (Brunetto et al., 2020; Etienne Parent et al., 2021).

Nutrient uptake curves allow inferring the amount and period of greatest demand for each evaluated nutrient, thus it is possible to establish a balance between nutrient supply and plant demand, in order to obtain high yields with fruits of excellent quality (Brunetto et al., 2016; Stefanello et al., 2020). The nutrient concentrations in the first-stage of fruit growth require a nutritional balance to guarantee succesful development and establishment at the definitive growing site (Orduz-Ríos et al., 2020).

Studies of nutrient uptake are more common in the international literature for annual crops such as vegetables (Adiele et al., 2021) and cereals (Silva et al., 2021), but they are very rare for fruit crops (Buitrago et al., 2021), especially star fruit. This is due to high added value and increasing demand of the international fruit markets. But the fruit is still under-exploited due to the lack of scientific information on mineral nutrition of the fruit. Nutrient uptake by plants depends on several environmental factors with emphasis on water availability, climate variability, and genetics (Alva et al., 2002; Adiele et al., 2021).

Rozane et al. (2011) reported for seedlings of star fruit that the uptake of nutrients followed a linear accumulation of dry matter of star fruit seedlings with the time of cultivation being greater in leaves > stem > roots. The greatest accumulation and nutrients in the leaves at the beginning of development are also reported by Franco et al. (2007), Freitas et al. (2011) and Adiele et al. (2021). The concepts of a critical dilution curve (Silva et al., 2021) and decrease as a function of the age and development of the plants was not observed in this study, which is believed to be due to the young characteristics of the plants, confirming Rozane et al. (2011) and Brunetto et al. (2020).

We hypothesize that the nutrient uptake behavior during star fruit formation is dependent on the water regime and the selected cultivar. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the growth and nutrient uptake of star fruit trees in the formation phase under two water regimes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted under field conditions with coordinates 21°15'22'' S and 48°18'58'' W at 615 m a.s.l. According to the Köppen classification, the local climate is of Aw type tropical megathermal with dry winter and average annual rainfall of 1,420 mm.

The soil is classified as typical eutrophic Red Latosol with clayey texture, kaolinite, hypoferric, and smooth undulating relief (Eutrustox) (Embrapa, 2018). Samples collected from 0-0.20 and 0.20-0.40 m layers are characterized in chemical terms with the following results: 4.5 and 4.1; 23 and 14; 196 and 139; 0.41 and 0.38; 1.4 and 1.0; 57 and 26; 16.8 and 8.7; 4.8 and 0.9; 7 and 2; 5.4 and 3.3; 19 and 7; 7 and 3; 42 and 38; 30.9 and 13.3; 73 and 51; 3 and 6; 42 and 26, respectively, for pH (CaCl2); OM (g dm-3); P; B; Cu; Fe; Mn; Zn; S-SO4 (mg dm-3); K; Ca; Mg; SB; H + Al; T; Al (mmolc dm-3) and V (%) (Raij et al., 2001).

Plant nursery seedlings were used to establish the orchard according to propagation techniques recommended by Donadio et al. (2001). The grafting of B-10 and Golden Star cultivars was carried out in hypobiotes from sexual propagation.

The experiment was carried out in sub-subdivided plots with two irrigation levels as plots (with and without irrigation), two cultivars (B-10 and Golden Star) as subplots, and seven plant collection times as sub-subplots; the first one was carried out with seedlings from the nursery at the time of trial implementation; and the others at 120, 240, 360, 480, 600 and 720 days after transplanting (DAT) in the field. The design was completely randomized with six replicates and totaled 168 experimental units.

With the aid of a furrow opener coupled to a tractor, a furrow of 0.40 m in the upper base and 0.40 m in depth was opened, making a planting hole of approximately 0.064 m3 (0.40 × 0.40 × 0.40 m). Spacing between plants was 5 × 5 m. Each hole received 20 L of organic compound based on bovine manure. Phosphorus was used at a dose of 180 g of P2O5 per hole in the form of simple superphosphate (Natale et al., 2008) and 2 g of Zn and 1 g of B (Donadio et al., 2001), with zinc sulfate and boric acid as sources.

After the planting of seedlings, crowning was performed, irrigating plants in the first 33 days after installation with the aid of a tank drawn by a tractor, applying 15 - 20 L of water per star fruit tree, establishing a watering shift of 2-3 d. Then, the micro-sprinkler irrigation system was installed, placing a 'ballerina' type micro-sprinkler per plant with a flow rate of 30 L h-1, 0.20 m from the trunk of each plant with a radius of approximately 2.0 m.

Irrigation management was performed with the aid of tensiometers installed at 0.20 m, 0.30 m, and 0.40 m of depth, with 0.20 m being used for irrigation decision-making, while the other two controled the applied water depth (Libardi, 1992), triggering the system when 30% of the water available in the soil was consumed. Three tensiometer batteries were installed, and irrigation decision-making was performed using the mean of the readings.

Up to 180 DAT, all the plants were irrigated so that seedlings and an orchard were established. After this period, irrigation was stopped in half of star fruit trees in order to characterize the statistical design treatments (with and without irrigation).

Covering fertilizations were carried out as suggested by Natale et al. (2008), beginning at 36 DAT. The recommended doses (140 g of N and 112 g of K2O per plant) were divided into four applications, with urea and potassium chloride as sources. At 270 DAT, new fertilization was performed, applying 200 g of N and and 50 g of K2O per plant in the form of ammonium sulfate and potassium chloride, also divided into four applications.

Up to 360 d, control of invasive plants in the canopy projection area was carried out when necessary with manual weeding. After this period, contact chemical desiccants were used. For weed management between rows, brush cutter mowers were used throughout the experimental period.

The following biometric variables were evaluated in all plots: height (from plant top to the end of the last expanded leaf); and stem diameter (0.10 and 0.40 m from plant top), determined with the aid of a digital caliper. Plants were then divided into stems and leaves, washed in distilled water and dried in an oven with forced air circulation at a temperature of 65ºC until reaching constant mass. The dry mass of the different parts was determined after determination of the dry mass of the stems and leaves. The material was ground and analyzed for nutrient content of plant tissues using a methodology described by Bataglia et al. (1983).

Nutrient uptake was obtained by multiplying the content of the element in the plant organ by the mass of dry matter corresponding to each part of the star fruit tree at the time of evaluation. The accumulation of nutrients in the shoots was obtained by the sum of the amounts present in the stems and leaves.

Based on the results, analyses of variance (F test) were performed for the several characteristics studied, as well as an regression study for the culture time., The regression model was used for all variables, resulting in significance by the F test, representing the evaluated characteristic.

For the exponential model, the adjustment equation (1) is represented by:

where

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

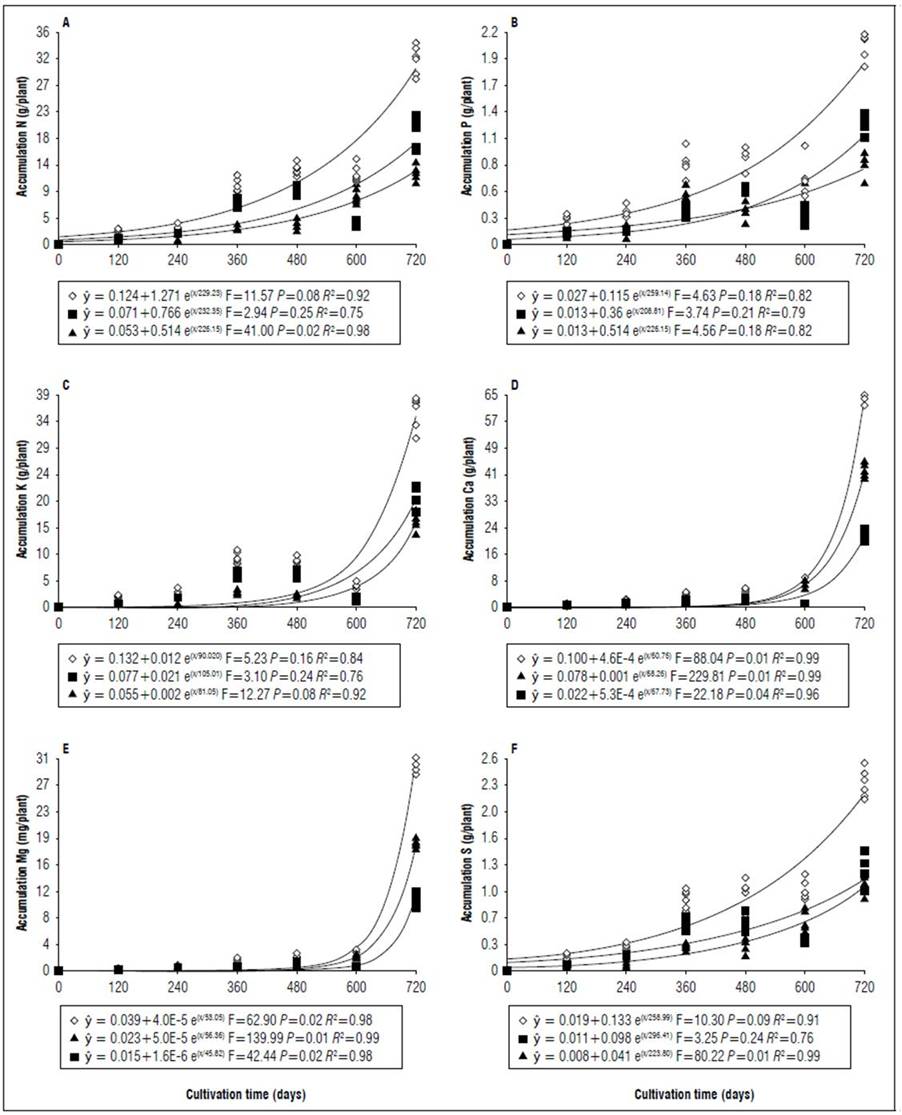

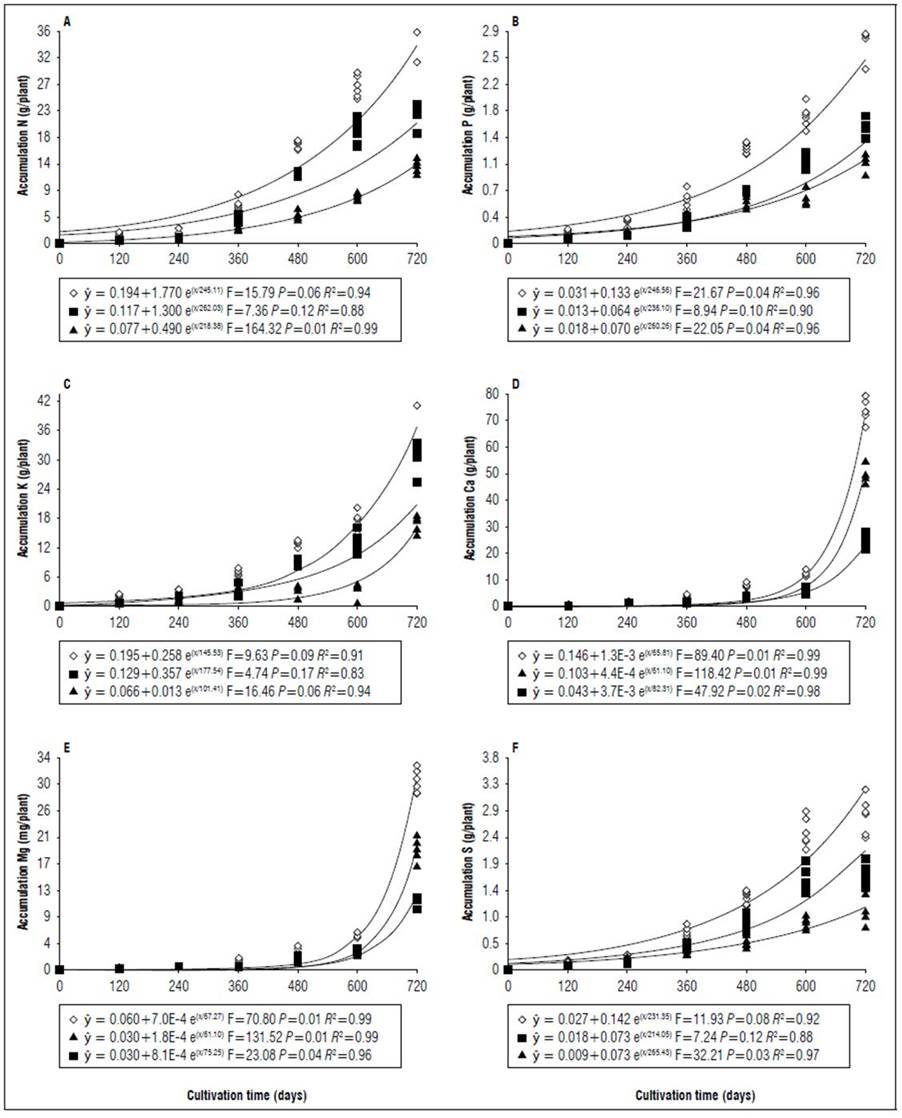

There was similarity in the adjustment of nutrient uptake equations with the dry matter mass (Fig. 1), resulting in greater occurrence of adjustments to the exponential model that can be explained by star fruit trees in the present experimental conditions at 720 d of cultivation having on average 5.0 (4.7%) for B-10 and 5.3 (4.9%) for Golden Star cultivars and on the weight of nutrients evaluated in the total dry matter mass for irrigated and rainfed regimes. Of the total accumulated nutrients, 57 (73%) for B-10 and 48 (67%) for Golden Star cultivars occurred in relation to the last evaluation at 600 DAT for irrigated and rainfed regimes (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9). Rozane et al. (2011) observed similarities in nutrient uptake in the same star fruit genotypes cultivated under hydroponics.

Figure 1. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on the dry mass of shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'B-10' cultivar grown under an irrigated regime (a) and non-irrigated regime (A) and non-irrigated regime (B) under field conditions and of ‘Golden Star’ cultivar grown under irrigated regime (C) and non-irrigated regime (D) under field conditions.

Figure 2. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on N (A), P (B), K (C), Ca (D), Mg (E) and S (F) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'B-10' cultivar in irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 3. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on B (A), Cu (B), Fe (C), Mn (D) and Zn (E) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'B-10' cultivar in irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 4. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on N (A), P (B), K (C), Ca (D), Mg (E) and S (F) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'B-10' cultivar in non-irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 5. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on B (A), Cu (B), F (C), Mn (D), and Zn (E) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'B-10' cultivar in non-irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 6. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on N (A), P (B), K (C), Ca (D), Mg (E) and S (F) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'Golden Star' cultivar in irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 7. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on B (A), Cu (B), Fe (C), Mn (D), and Zn (E) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'Golden Star' cultivar in irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 8. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on N (A), P (B), K (C), Ca (D), Mg (E) and S (F) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'Golden Star' cultivar in non-irrigated regime under field conditions.

Figure 9. Equations, F value, significance, and determination coefficient (R 2 ) obtained in regression studies on the effects of cultivation time on B (A), Cu (B), Fe (C), Mn (D) and Zn (E) uptake in shoots (◊), leaves (■) and stems (▲) of 'Golden Star' cultivar in non-irrigated regime under field conditions.

Nutrient uptake by shoots at 720 DAT differed. For the Golden Star cultivar under rainfed regime and for B-10 cultivar under both irrigation regimes no difference was observed. They followed the sequence Ca > K > N > Mg > Mn > Fe > Zn > B > Cu, and for Golden Star cultivar in the irrigated regime, the accumulation sequence was Ca > K > N > Mg > Mn > P > S > Fe > Zn > B > Cu.

The mean percentage values in relation to the dry matter mass of shoots for both cultivars in both water regimes was 0.90, 0.07, 1.12, 1.90, 0.83, 0.08, 0.0016, 0.0004, 0.0095, 0.0516, and 0.0032 for N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, B, Cu, Fe, Mn and Zn (Fig. 2 to 9) 95.03% remained for the dry matter mass of shoots (Tab. 1 and 2).

Table 1. F value and variation coefficients of the factors cultivar, irrigation, cultivation time, and their interaction on the nutrient uptake in the different organs of B-10 and Golden Star cultivars.

| Factors | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | S | B | Cu | Fe | Mn | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem | |||||||||||

| Cultivation time (T) | 1369.45** | 417.71** | 1166.18** | 3043.75** | 3655.69** | 591.85** | 1496.43** | 228.68** | 1079.64** | 4291.45** | 530.16** |

| Irrigated (I) | 22.844** | 26.38** | 8.46* | 51.50** | 48.12** | 5.43* | 124.24** | 23.53** | 345.73** | 1176.85** | 0.77NS |

| Cultivars (C) | 4.39NS | 65.30** | 5.87* | 0.24NS | 19.13** | 85.56** | 8.05* | 21.80** | 3.53NS | 284.83** | 0.60NS |

| Interaction (I x C) | 0.92NS | 0.26NS | 1.70NS | 0.61NS | 0.63NS | 34.96** | 0.02NS | 9.69* | 11.30** | 526.58** | 0.30NS |

| Interaction (I x T) | 16.69** | 17.83** | 9.51** | 11.92** | 4.21** | 48.99** | 24.18** | 3.87** | 119.43** | 1152.80** | 4.79** |

| Interaction (C x T) | 13.27** | 24.72** | 5.13** | 2.82* | 12.76** | 49.55** | 22.49** | 10.00** | 7.06** | 435.19** | 5.65** |

| Interaction (I x C x T) | 2.23* | 2.59* | 2.29* | 7.43** | 0.68NS | 36.82** | 7.28** | 1.33NS | 10.31** | 633.73** | 2.86* |

| CV (%)(1) | 10.6 | 24.2 | 27.2 | 14.1 | 9.85 | 26.7 | 14.7 | 43.9 | 18.2 | 13.5 | 17.6 |

| CV (%)(2) | 19.7 | 24.0 | 20.1 | 18.2 | 19.1 | 22.7 | 17.2 | 34.3 | 18.3 | 13.9 | 27.5 |

| CV (%)(3) | 14.3 | 22.4 | 20.4 | 17.0 | 16.4 | 23.2 | 14.7 | 43.3 | 21.6 | 12.8 | 20.7 |

| Leaves | |||||||||||

| Cultivation time (T) | 1504.08** | 1800.30** | 1337.75** | 2421.35** | 3607.64** | 829.28** | 1521.88** | 619.08** | 1476.01** | 1036.77** | 679.56** |

| Irrigated (I) | 190.47** | 182.56** | 57.11** | 107.84** | 107.77** | 213.64** | 306.24** | 67.98** | 605.62** | 172.65** | 33.45** |

| Cultivars (C) | 44.97** | 65.81** | 76.09** | 0.35NS | 0.22NS | 13.77** | 0.01NS | 0.77NS | 78.71** | 14.33** | 23.00** |

| Interaction (I x C) | 31.99** | 4.75ns | 14.80** | 13.29** | 1.23NS | 5.31** | 18.92** | 27.01** | 10.58** | 15.05** | 29.49** |

| Interaction (I x T) | 126.96** | 87.12** | 49.40** | 21.29** | 32.30** | 134.12** | 131.91** | 24.82** | 283.32** | 119.88** | 116.94** |

| Interaction (C x T) | 24.83** | 39.15** | 44.67** | 5.17** | 18.20** | 35.77** | 18.69** | 5.75** | 33.68** | 72.85** | 28.31** |

| Interaction (I x C x T) | 5.01** | 4.25** | 4.39** | 3.40** | 2.46** | 2.90* | 8.34** | 22.61** | 6.62** | 12.01** | 18.20** |

| CV (%)(1) | 12.4 | 11.1 | 20.1 | 14.4 | 14.9 | 20.3 | 15.9 | 23.1 | 17.6 | 18.6 | 16.9 |

| CV (%)(2) | 7.3 | 11.5 | 17.9 | 15.9 | 19.0 | 13.1 | 15.2 | 23.6 | 15.2 | 21.6 | 14.1 |

| CV (%)(3) | 13.0 | 12.2 | 17.2 | 18.3 | 14.4 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 22.6 | 15.8 | 15.6 | 16.8 |

| Aerialparts | |||||||||||

| Cultivation time (T) | 2589.25** | 1318.70** | 2068.08* | 6181.11** | 6895.87** | 1285.18** | 2038.72** | 466.64** | 2449.63** | 3648.38** | 788.40** |

| Irrigated (I) | 161.15** | 79.59** | 48.27** | 111.28** | 169.54** | 54.93** | 274.16** | 51.93** | 9.27.46** | 662.65** | 8.33* |

| Cultivars (C) | 22.91** | 80.16** | 51.66** | 0.49ns | 11.69** | 30.14** | 1.27NS | 9.10* | 59.37** | 12.35** | 3.60NS |

| Interaction (I x C) | 11.55** | 0.18NS | 10.74** | 0.65NS | 1.47NS | 12.60** | 9.35* | 0.06NS | 0.02NS | 33.93** | 0.91NS |

| Interaction (I x T) | 83.43** | 49.72** | 43.67** | 27.62** | 19.25** | 53.11** | 113.97** | 9.44** | 315.93** | 578.46** | 34.02** |

| Interaction (C x T) | 34.19** | 47.13** | 32.28** | 7.07** | 7.56** | 25.13** | 23.50** | 4.85** | 20.13** | 42.96** | 15.57** |

| Interaction (I x C x T) | 5.50** | 3.78** | 5.14** | 6.67** | 2.06NS | 25.04** | 7.27** | 4.21** | 13.20** | 148.91** | 7.94** |

| CV (%)(1) | 9.8 | 15.4 | 18.0 | 11.2 | 7.7 | 19.4 | 14.6 | 28.2 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 16.1 |

| CV (%)(2) | 9.6 | 15.9 | 16.2 | 13.0 | 14.4 | 12.2 | 14.6 | 27.0 | 11.9 | 15.0 | 20.4 |

| CV (%)(3) | 10.0 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 27.9 | 13.1 | 10.1 | 16.2 |

(1), (2) and (3) Variation coefficients for plot, subplot and sub-subplot, respectively. NS, *, **: non-significant and significant at P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively.

Table 2. Analysis of variance and average results of the dry matter mass (g/plant) of stem and leaves of growing star fruit trees, cultivated in irrigated and non-irrigated regimes under field conditions.

| Cultivation time (T) days | Stem | Leaves | Aerialparts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9.05 | 4.91 | 13.97 |

| 120 | 38.98 | 36.13 | 75.11 |

| 240 | 59.17 | 68.85 | 128.02 |

| 360 | 320.32 | 236.57 | 556.89 |

| 480 | 538.96 | 499.98 | 1038.94 |

| 600 | 1026.63 | 447.81 | 1474.45 |

| 720 | 2299.25 | 1169.71 | 3468.96 |

| Test F | 6337.41** | 3785.41** | 7647.20** |

| Irrigated (I) | |||

| Irrigated | 665.38 | 399.56 | 1064.94 |

| Non- irrigated | 561.01 | 304.43 | 865.44 |

| Test F | 132.23** | 315.14** | 238.07** |

| Cultivars (C) | |||

| B-10 | 634.72 | 348.40 | 940.07 |

| Golden Star | 591.67 | 355.59 | 990.31 |

| Test F | 22.83** | 2.79ns | 18.36** |

| Irrigated (I x C) | 20.50** | 27.20** | 28.47** |

| I in C1 | 24.70** | 116.70** | 61.56** |

| I in C2 | 128.82** | 296.21** | 225.42** |

| Interaction (I x T) | 69.82** | 257.76** | 175.50** |

| I in T1 | 0.01NS | 0.00NS | 0.01NS |

| I in T2 | 0.05NS | 0.02NS | 0.01NS |

| I in T3 | 0.07NS | 0.71NS | 0.34NS |

| I in T4 | 7.21** | 36.99** | 22.84** |

| I in T5 | 245.77** | 96.48** | 256.32** |

| I in T6 | 299.80** | 1723.77** | 1016.81** |

| I in T7 | 15.35** | 9.84** | 18.64** |

| Interaction (C x T) | 20.60** | 34.15** | 36.01** |

| C in T1 | 0.03NS | 0.20NS | 0.03NS |

| C in T2 | 0.01NS | 2.88NS | 0.66NS |

| C in T3 | 1.25NS | 5.43NS | 3.59NS |

| C in T4 | 5.13* | 14.32NS | 11.64** |

| C in T5 | 14.80** | 0.77NS | 6.05* |

| C in T6 | 118.33** | 191.32** | 207.38** |

| C in T7 | 7.47** | 2.03NS | 1.91NS |

| Interaction (I x C x T) | 18.03** | 11.65** | 22.46** |

| CV (%)(1) | 9.6 | 9.9 | 8.7 |

| CV (%)(2) | 9.5 | 7.7 | 7.9 |

| CV (%)(3) | 8.3 | 9.3 | 7.1 |

(1), (2) and (3) Variation coefficients for plot, subplot, and sub-subplot. NS, *, **: non-significant and significant at P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively.

The order of nutrient uptake differs from that verified by Rozane et al. (2011) for the same genotypes, since they observed that N and K were required, as well as from that reported by Freitas et al. (2011) for Nota-10 star fruit cultivar, with N and K being the most required, both studies were conducted under hydroponics. However, Ondo et al. (2012) observed that Ca, followed by potassium, are the most exported nutrients in fruit plants in general. Variations in the order of nutrient uptake in fruit trees are commonly reported in the literature, when different genetic materials and cultivation techniques are used, in addition to the cultivation time such as for guava (Augostinho et al., 2008; Franco et al., 2007).

The greatest variations in the accumulation of nutrients in the shoots at 720 DAT between the genotypes occurred in the micronutrients, for both cultivars the accumulation was on average 36% lower when there was no irrigation, an outstanding observation for Mn which had the lowest accumulation 68 and 62%, respectively for 'B-10' and 'Golden Star' (Fig. 3, 5, 7 and 9). For macronutrients, the highest accumulation also occurred in irrigated areas that had on average 13% more in relation to non-irrigated areas (Fig. 2, 4, 6 and 8). This confirmed the observations of Medyouni et al. (2021), who indicated a reduction in the size of tomato leaves and fruits when subjected to water stress. The fundamental role of water in the nutritional stability of fruit trees was reported by Rozane et al. (2009) due to its more expressive relative importance in the supply of nutrients due to transport via mass flow (Epstein and Bloom, 2006). Jiménez-Suancha et al. (2015) agree that water participates in most of the physiological processes that occur in the growth and productivity of plants that includes the transport and assimilation of nutrients.

During cultivation, there were differences in nutrient uptake in leaves, stems, and shoots (Tab. 1). At the end of the experimental period, during the irrigated regime, there was greater Ca, Mg, Cu and Mn uptake in the stems in relation to the leaves in both cultivars, in addition to greater Fe and Zn uptake for B-10 cultivar (Fig. 2, 3, 6 and 7). For the non-irrigated system in both cultivars under study, at 600 DAT the greatest nutrient uptake occurred in the stems in relation to the leaves, due to a reduction in the dry matter mass of the latter organ (Tab. 2) because of the abscission caused by water deficit. However, for the non-irrigated regime at 720 DAT, the greater nutrient uptake in leaves in relation to the stems of B-10 cultivar followed the order: K, N, P, S, Mn, Fe, and B; in the Golden Star cultivar, the sequence was K, N, P, Mn, Fe, and Cu (Fig. 4, 5, 8 and 9), indicating that stems were important reserve organs for Ca and Mg.

The period of greatest nutritional requirement of star fruit trees was between 600 and 720 DAT, a period that also corresponded to greater dry matter mass accumulation (Fig. 1). Nutrient uptake in both cultivars, at different cultivation times, presented variable behaviors as a function of water regime, organ analyzed, and nutrient (Tab. 1). For all nutrients the largest accumulations occurred in the irrigated regime, with values higher than those obtained for the non-irrigated regime of 8.4; 7.4; 7.3; 13.7; 3.4 and 5.0 for N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S macronutrients, and 27.7; 26.1; 45.5; 64.1; 19.7; for B, Cu, Fe, Mn and Zn micronutrients (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). These data agreed with Aquino et al. (2012).

It seems reasonable to expect that the greatest nutrient uptake occurs in plants managed under irrigation, given the fundamental role of water in the absorption of elements, as well as the changes it causes in soil and plants. Epstein and Bloom (2006) indicate that water is essential for plant growth because it plays a role in the transport of mineral elements in the plant and suggest that an ideal water potential in the zone of root absorption facilitates contact, absorption, and stabilization of plant nutrients. Amijee et al. (1991) suggest that water directly and indirectly affects mechanistic models that simulate nutrient uptake, such as the diffusion coefficient of an element in water, as well as the volumetric content of water in soil and the inflow rate of water by roots, the latter having an important role in the transport of nutrients by mass flow.

The lower accumulation of nutrients in the aerial part of star fruit plants at 720 DAT when they were submitted to the non-irrigated regime (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) was not reflected in the decrease in the accumulation of dry matter of the cultivars (Fig. 1). Small variations in water availability may allow the maintenance of an adequate photosynthetic rate and the maintenance of production in some species (Molina-Montenegro et al., 2011). Mahouachi, (2009) indicates that magnesium may be the element that would best protect the photosynthetic machine from water stress. In the present study, for the conditions and cultivars evaluated, no damage was observed in the accumulation of magnesium that could contribute to the explanation that the water deficit was not sufficiently severe and thus did not affect the accumulation of dry matter between treatments with and without irrigation at 720 DAT (Fig. 1).

Regarding the cultivar factor, considering shoots (stem + leaves), the Golden Star cultivar had the highest accumulations in higher amounts of macronutrients (g/plant) at 720 d of N (2.4); P (1.0); K (16.2); Mg (0.1), and S (0.7); and for micronutrients (mg/plant), Fe (99.9) and Mn (761.9) while Cu accumulated 8.7 mg/ plant, higher in the B- 10 cultivar (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). Ca, B and Zn nutrients were not significant (Tab. 1).

CONCLUSIONS

The nutrient uptake curve and the mean accumulation rate followed the dry matter mass accumulation of growing star fruit trees.

Nutrient uptake by shoots at 720 DAT differed, and for Golden Star cultivar in the rainfed regime and for B-10 cultivar in both irrigation regimes no difference was observed and followed the sequence: Ca> K> N> Mg> S> P> Mn> Fe> Zn> B> Cu, for Golden Star cultivar in the irrigated regime, the accumulation sequence was: Ca> K> N> Mg> Mn> P> S> Fe> Zn > B> Cu.

The highest nutrient uptake occurred in the irrigated regime regardless of cultivar. The 'Golden Star' accumulated, on average, larger amounts of N, P, K, Mg, S, Fe and Mn than 'B-10'.