INTRODUCTION

In Mexico, calla lily production is concentrated in the provinces of Veracruz, Puebla, Jalisco, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Colima, and the State of Mexico (Cruz-Castillo and Hernández-Montes, 2022). Its production is limited by Pectobacterium carotovorum, also known as Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora (Trejo-Téllez et al., 2013; Cruz-Castillo and Torres-Lima, 2017) and other unknown pathogens (Delgado-Paredes et al., 2021). Calla lilies are popular in Mexico and are used to decorate weddings and other celebrations (Cuellar-Mandujano et al., 2022). Most calla lilies produced in Mexico are perennial with white spathes. In Latin America, this calla lily grows in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia (Casierra-Posada et al., 2014), Ecuador, and Guatemala (Cruz-Castillo, 2022).

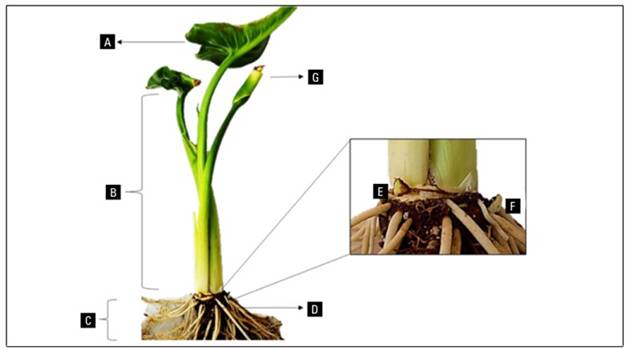

The calla lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica[L.] Spreng.) is the most well-known species (Fig. 1), but there are other species with flowers with various colors from pink to brown. The genus Zantedeschia is divided into two sections or botanical groups: the Zantedeschia section and the Aestivae section (He et al., 2020). The Zantedeschia section comprises the species Z. aethiopica ([L.] Spreng.) and Z. odorata Perry, while the Aestivae section includes Z. albomaculata ([Hook.] Baill.), Z. rehmannii (Engl.), Z. elliottiana ([Watson] Engl.), Z. jucunda (Letty), Z. valida (Singh.), and Z. pentlandii ([Watson] Wittm.) (Wei et al., 2017). It has been demonstrated that the Aestivae section is more susceptible to soft rot caused by bacteria of the genus Pectobacterium due in part to the ecological adaptation of each section (Guttman et al., 2021). This susceptibility has reduced the production of calla lilies, leading to the introduction of in vitro cultivation techniques to obtain pathogen-free plants (Nery et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Calla lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica L. Spreng.) var. Utopia. A, leaf; B, petiole; C, roots; D, rhizome; E, apical bud; F, adventitious bud; G, immature spathe.

A review regarding tissue culture of Zantedeschia was published (Sun et al., 2023), but rot causal agents of explants were not considered. The micropropagation of Z. aethiopica has often been difficult due to contamination of cultured rhizome tissue (Martínez-Hernández, 2022). Therefore, this review focuses on in vitro techniques in Zantedeschia, highlighting phytopathological aspects to reduce the contamination of the explants.

Phytopathology of the Zantedeschia genus

The main factor limiting the production of calla lilies is disease. Soft rot, caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum poses a significant worldwide threat to Zantedeschia crop (Githeng’u et al., 2016). Other associated pathogens include Pseudomonas marginalis (Brown) Stevens (Krejzar et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2014), Pseudomonas veronii Elomari et al., Chryseobacterium indologenes (Yabuuchi et al.) Vandamme et al. (Mikiciński et al., 2010), Cellvibrio zantedeschiae sp. Nov. (Sheu et al., 2017), Pectobacterium zantedeschiaeWaleron et al. (Waleron et al., 2019), and Pectobacterium aroidearum Nabhan et al. (Chen et al., 2020). The main symptoms of this disease include dwarfing, chlorosis along the leaf margin progressing in a "V" shape that may turn brown, stem bending, and eventual desiccation (Ciampi et al., 2009).

Viruses that often attack Zantedeschia include dasheen mosaic virus (DsMV), classified as the most prevalent among Aroids (Cafrune et al., 2011). Its distribution was recorded in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where crops presented symptoms such as yellowing and distortion of leaves as well as mosaic and chlorotic ring symptoms (Grausgruber-Gröger et al., 2016).

For the konjac mosaic virus (KoMV), Myzus persicae (Sulzer) and Aphis gossypii (Glover) were identified as main vectors, along with vegetative propagation and seed transmission. Symptoms appear as mosaics, green islands, interveinal chlorosis, leaf deformity, short peduncles, and discolored pigmented spots on the spathe (Liao et al., 2020).

The calla lily latent virus (or zantedeschia mild mosaic virus [ZaMMV]) is a potyvirus isolated from the Black Magic cultivar. It manifests as yellow spots and stripes, green islands, and an unusually mild mosaic (Rizzo et al., 2015). For the detection of viruses, Zantedeschia has been cultured in vitro (Purmale et al., 2023). However, with this type of propagation the viruses were not eliminated. Therefore, studies on thermotherapy, chemotherapy, cryotherapy or electrotherapy (Szabó et al., 2024) to eliminate virus in Zantedeschia could be evaluated.

Pathological control and eradication methods

Endogenous contamination is a recurring issue in in vitro establishment, particularly in rhizome tissue. Sanitary management before in vitro cultivation is recommended. Species of the Pectobacterium family propagate easily through decaying plant material, and there are no efficient control agents for the disease they cause (van der Wolf et al., 2021; Niyokuri and Nyalala, 2023). Soil fumigation with metam sodium and the application of antagonistic bacteria CAE 01 of the Enterobacteriaceae family reduced the percentageof infection in rhizomes (García-López, 2010). As a biological control for P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum, the high specificity of the bacteriophage virus PP1 of the Podoviridae family was studied (Lim et al., 2013). The use of Bacillus velezensis (Ruiz-García et al.) (other scientific name Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum) reduced the growth of the phytopathogen in both in vitro and field conditions (He et al., 2021). Protein profiles from in vitro and in vivo conditions for P. carotovorum following interaction with Z. elliottiana 'Black Magic' were also generated. Using two-dimensional electrophoresis, 53 essential proteins for their virulence were identified, showing differential expression in vitro, in vivo, or both compared to the control (Wang et al., 2018).

Methods of incorporation to in vitro conditions

The eradication of pathogens prior to calla lily in vitro establishment has been a challenge. The use of mercury chloride (HgCl2) at 0.1-0.2% (w/v) for 15 min (Xiao-Chun, 2010) or for 30 min for leaf and rhizome at doses of 0.1 and 0.2% (w/v) respectively with prior treatment with benomyl at 1% (w/v) in shaking for 30 min (Hlophe et al., 2015) yielded good results. Even doses of 0.5% of HgCl2 (w/v) for 15 min were effective at this stage in Z. rehmannii with pre-treatment of immersion in 70% ethanol (v/v) for 30 s (Kulpa, 2016). Despite the effectiveness of these treatments, a concentration of 0.25 mg L-1 has negative environmental consequences on amphibian development (Muñoz-Escobar and Palacio-Baena, 2010).

Hernández-Villaseñor et al. (2018) disinfected with a 15% (w/w) chlorine solution followed by 500 mg L-1 of streptomycin, 500 mg L-1 of oxytetracycline, and 500 mg L-1 of carboxamide for 60 min. Finally, the explants were placed into a 70% (v/v) ethanol solution for 30 s. Similarly, the application of chlorine dioxide (ClO2) at a concentration of 60 to 180 mg L-1 (v/v) for 5 min followed by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at 5% (v/v) for 15 min provided a survival rate >75% for Z. aethiopica (Chen et al., 2017).

Due to the need to implement disinfestation protocols that have less environmental impact, studies based on antibacterial activity of Coptis chinensis (Franch.) extract has been developed against soft rot. 100% C. chinensis made an inhibition effect comparable to streptomycin sulphate (Githeng’u et al., 2016), an antibiotic widely used in the 90’s. This protocol has not been tested on Zantedeschia explants. Hashemidehkordi et al. (2021) evaluated the effect of hot water in the disinfection of rhizome explants and achieved a survival rate of 90% at 45°C for 35 min followed by immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 s and 1% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 10 min. This procedure represents a good alternative to reduce the use of previously mentioned products and their impact in terms of environmental, economic impact, and antibiotic resistance. Table 1 shows the control methods for the in vitro culture of calla lilies.

Table 1. Methods for controlling contaminants in Zantedeschia spp. cultured in vitro.

| Plant material | Origin of explant | Control method | Survival rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z. hybrida | Rhizome | HgCl2 at 0.1-0.2% for 15 min for rhizome segments | Not reported | Xiao-Chun, 2010 |

| Z. aethiopica | Leaf and rhizome | HgCl2 at 0.2% for rhizome segments and 0.1% for leaves for 30 min | 28% in rhizome and 78.3% in leaf | Hlophe et al., 2015 |

| Z. rehmannii | Rhizome | Immersion in 0.5% HgCl2 for 15 min | 73% | Kulpa, 2016 |

| Z. aethiopica | Rhizome | 15 % chlorine + 500 mg L-1 streptomycin, 500 mg L-1 oxytetracycline, and 500 mg L-1 captan for 60 min + 70 % ethanol (v/v) for 30 s | Not reported | Hernández-Villaseñor et al., 2018 |

| Z. aethiopica | Rhizome-buds | ClO2 at 60 to 180 mg L-1 (v/v) for 5 min + 5% H2O2 (v/v) for 15 min | >75 % | Chen et al., 2017 |

| Zantedeschia spp. ‘Orania’ and ‘Sunclub’ | Rhizome-buds | Hot water bath at 45°C for 35 min + immersion in 70 % ethanol for 30 s and 1 % sodium hypochlorite (v/v) for 10 min | >90 % | Hashemidehkordi et al., 2021 |

| Z. aethiopica ‘Déjà vu’ and ‘Utopia’ | Rhizome | Agrimicyn® (2 g L-1) added to the fungicide Benomyl® (2 g L-1) | ‘Utopía’: 60%; ‘Déjà vu’; 80 % | Martínez-Hernández, 2022 |

| Z. aethiopica | Seed | 70 % ethanol for 1 min + 10% NaOCl for 15 min, and 10 min of 30% H2O2 | 100 % | Martínez-Hernández, 2022 |

In vitro propagation of Z aethiopica cultivars in Mexico has not been easy due to contamination of the explants. The antibiotic Agrimycin® (2 g L-1) added to the fungicide Benomyl® (2 g L-1) reduced endophytic contamination by fungi and bacteria in explants from rhizomes of the cultivars Deja Vú and Utopia. For seed germination, in vitro contamination was not observed when using 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by 10% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, and 10 min of 30% hydrogen peroxide (Martínez-Hernández, 2022).

Direct organogenesis

The process of organogenesis provides the basis for asexual plant propagation largely from nonmeristematic somatic tissues (Schwarz and Beaty, 2000). Through this method, pathogen-free plants have been obtained via meristem culture (Tab. 2). In Z. aethiopica, the addition of benzylaminopurine (BAP) at 22.19 μM produced 2.6 shoots per explant (Ribeiro et al., 2014). Rhizomes and tubers have been the main organs targeted for obtaining explants despite the likelihood of presenting endogenous contamination. Singh et al. (2009) obtained 5 to 6 shoots of Z. aethiopica 10.0 mg L-1 of BAP supplemented with 50 mg L-1 of ascorbic acid. In Z. rehmannii, culture was obtained using a concentration of 3 mg L-1 BAP, and a rate of 4.3 shoots per explant was obtained with 2.5 mg L-1 BAP (Kulpa, 2016).

Table 2. Research relating to the direct organogenesis of Zantedeschia spp.

| Plant material | Origin of the explant | Medium | Growth regulators | Multiplication rate (shoots per explant) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z. aethiopica | Rhizome | MS | 10.0 mg L-1 BAP, 50 mg L-1 ascorbic acid, 25 mg L-1 adenine sulfate, L-arginine and citric acid | 5-6 | Singh et al., 2009 |

| Z. rehmannii | Rhizome-buds | MS | 3 mg L-1 and 2.5 mg L-1 BAP + 100 mg L-1 ascorbic acid | 4.3 | Kulpa, 2016 |

| Z. aethiopica | Shoot tip | MS | 22.19 μM BAP | 2.6 | Ribeiro et al., 2014 |

Indirect organogenesis

Shin et al. (2020) reconstructed the process of regeneration of new shoots from callus and differentiated four stages: acquisition of pluripotency (in a medium rich in auxins), formation of pro-meristems, establishment of shoot progenitor, and shoot growth. Some species from the genus Zantedeschia have been propagated through this pathway (Tab. 3).

Table 3. Research related to indirect organogenesis of Zantedeschia spp.

| Plant material | Origin of the explant | Medium | Growth regulators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z. hybrida ‘Feng Yang’ | Rhizome | MS | BA (2.0 mg L-1) + NAA (0.1 ~ 0.2 mg L-1) | Xiao-Chun, 2010 |

| Zantedeschia spp. ‘Sunlight’, ‘Chiante’ and ‘Pink ‘Persuasion’ | Apices derived from callus shoots and adventitious shoots | MS + 70-90 g L-1 sucrose | BA (2-3 mg L-1) | Lee and Ko, 2005 |

| Zantedeschia sp. ‘Pink Giant’ | Leaf | MS | 2,4-D (2.0 mg L-1) and BA (2.0 mg L-1) or NAA (2.0 mg L-1) and BA (2.0 mg L-1) | Gong et al., 2008 |

MS, Murashige and Skoog.

In vitro dedifferentiation in Z. aethiopica and Z. elliottiana was observed in petiole, leaf, and spathe segments, achieving over 80% callus formation on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with indoleacetic acid (IAA) at 0.5 mg L-1 + BAP 2.0 mg L-1 for leaves; IAA (2.0 mg L-1) + BAP (2.0 mg L-1) for spathes; and IAA (1.0 mg L-1) + BAP (2.0 mg L-1) for petioles. The petioles showed the greatest dedifferentiation capacity among the organs mentioned. Furthermore, Z. elliottiana demonstrated a higher differentiation capacity than Z. aethiopica, as well as the ability to generate callus at high doses of BAP (4.0 mg L-1) combined with NAA (0.1 mg L-1) (Jonytienè et al., 2017). In Zantedeschia spp., callus formation was induced by culturing leaf segments on MS medium supplemented with 2,4-D (2.0 mg L-1) and BA (2.0 mg L-1) or with naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) (2.0 mg L-1) and BA (2.0 mg L-1) (Gong et al., 2008).

The hormonal balance between auxins and cytokinin is crucial in the indirect organogenesis of Zantedeschia in vitro (Cheng et al., 2013). Lee and Ko (2005) achieved up to 56.7% callus formation on a medium containing BA (2.0 mg L-1) and a shoot regeneration rate of 70% at 3.0 mg L-1 of BA. Cytokinin induced the formation of multiple shoots; 2ip (1.0 mg L-1), BA (5.0 mg L-1), and BA (1.0 mg L-1) brought on 16, 14, and 12 multiple shoots in the cultivars Sunlight, Chiante, and Pink Persuasion, respectively. Xiao-Chun (2010) promoted callus formation on an MS medium + 2.0 mg L-1 BA + 0.1-0.2 mg L-1 NAA and achieved 100% rooting with an MS medium + indole butyric acid (IBA) at a concentration of 0.3 mg L-1.

Somatic embryogenesis

Few studies on induced somatic embryogenesis in Zantedeschia exist (Tab. 4). The first reported research on somatic embryogenesis in calla lilies was conducted on three hybrids with explants derived from rhizomes and anthers. However, the formation of somatic embryos was only achieved from rhizome segments. The best results were obtained in media supplemented with plant growth regulators (Nic-Can et al., 2016), as NAA (2.0 mg L-1) and BA (0.6 to 2.0 mg L-1). Conversion to normal seedlings was achieved in MS medium supplemented with vitamins, micro and macronutrients, 1.0 mg L-1 2iP, 3% sucrose, and 0.7% agar (Duquenne et al., 2006).

Stem segments containing apical meristems derived from the cultivar Gag-si were cultured on MS medium. A 25% induction rate of yellow embryogenic calli was obtained with MS + 0.5 mg L-1 NAA and 1.5 mg L-1 BA. In the regeneration experiments from embryogenic calli, the MS medium supplemented with 0.5 mg L-1 IAA and 2.0 mg L-1 BA showed the highest rates, approximately 85 ~ 90%. Table 4 summarizes research related to somatic embryogenesis of Zantedeschia species (Han and Kim, 2019).

Table 4. Research related to somatic embryogenesis of Zantedeschia spp.

| Species | Origin of explant | Medium | Growth regulators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zantedeschia hybrids | Rhizomes and anthers | MS | BA (0.22 mM) | Duquenne et al., 2006 |

| Zantedeschia hybrida | Petiole | MS | 0.5 mg L-1 NAA, 1.5 mg L-1 BA, 0.5 mg L-1 IAA, 2.0 mg L-1 BA | Han and Kim, 2019 |

Plant mass propagation through bioreactor

Research with Zantedeschia grown in liquid media has focused on determining the optimal frequency of immersion, comparing temporary immersion systems (TIS) with other culture systems such as semisolid and agitated liquid, and the effect of growth regulators. A multiplication coefficient of 9.7 shoots per explant was obtained using active buds from Zantedeschia spp rhizomes in a modified MS medium with 100 mg L-1 myo-inositol, 1 g thiamine, 4 mg L-1 BAP, and paclobutrazol at 0.3 mg L-1 with an immersion frequency of 4 h every 4 min (Sánchez et al., 2009). Sánchez et al. (2010) achieved multiplication rates of 7.93, 10.66, and 11.30 shoots per explant in an MS medium + 1, 2, and 4 mg L-1 BA and an immersion frequency of 4 h every 3 min.

In vitro zygotic embryos germination

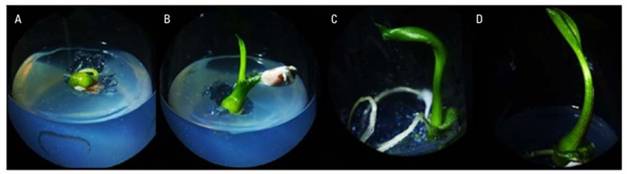

Mature embryos from in vitro seeds have also been used to generate transgenic plants of Zantedeschia (Sun et al., 2022). Studies on the in vitro germination of embryos (seeds) of species in the genus Zantedeschia determined that temperatures of 14-20°C, high concentrations of sucrose and agar (Ngamau, 2001), fruit maturity, and GA3 can influence the germination rate (Nery et al., 2015). In vitro germination of Zantedeschia studies focused on early flowering, and salt and/or temperature tolerance. Seedlings from seeds established at low temperatures had greater growth under lower night temperatures than those germinated at high temperatures, and clones from seeds exposed to high levels of sodium chloride (NaCl) achieved greater growth. Also, early seeds showed better growth, early flowering, and a higher number of spathes (Ngamau, 2008). The germination of Z. aethiopica seeds in vitro was enhanced in a medium supplemented with 3.0 mg L-1 of GA3 and 0.3 mg L-1 of BAP, with germination occurring 35 d after establishment (Martínez-Hernández, 2022) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Growth in vitro of white calla lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica L. Spreng) seed cultured. A, development of the radicle and emergence of the plumule; B and C, elongation of the root and plumule; D., first leaf.

Martínez-Hernández et al. (2022) isolated zygotic embryos from mature and immature white calla lily fruits. The seeds were pretreated with sterile water and 30% (v/v) H2O2. The isolated embryos were cultured in a medium with MS salts (100%) supplemented with BAP (0, 0.3 and 3 mg L -1) and GA3 (0, 0.3 and 3.0 mg L-1). The embryos’ development was not affected by the composition of culture media, the seed pretreatments or the fruit ripening stage (Fig. 3).

In vitro flowering

Naor et al. (2004a) investigated the hormonal control of floral induction and the development of inflorescence in vitro in day-neutral plants of Zantedeschia spp., as well as the effects of GA3 and BA on the development of inflorescences in regenerated tissue culture seedlings. The seedlings were immersed in GA3 and BA solutions before replanting in new media. GA3 was found to be essential for the transition from the vegetative to the reproductive stage. Inflorescence development in the apical bud was observed after 30-50 d in seedlings treated with GA3 grown in vitro. However, the resulting inflorescences had incomplete male and female flowers. BA did not affect flower induction but in the presence of GA3, BA at 4.4 M enhanced inflorescence differentiation. They concluded that the floral initiation was not influenced by environmental stimuli and that the inflorescence development in the apical bud resembled natural conditions (Naor et al., 2004a). GA3 had a dual action in the flowering process, inducing inflorescence differentiation and promoting floral stem elongation. They inferred that the flowering pattern might be a gradient in the distribution of GA, likely controlled by the apical dominance of the primary bud (Naor et al., 2004b).

Future studies

Genotype influences the growth and development of explants in vitro. Thus, the propagation of new varieties will need specific protocols. The evaluation of artificial light sources for illumination to improve the quality of the explants may be explored. The use of nanomaterials in modulating in vitro Zantedeschia tissue growth and development could also be evaluated. Additionally, organic additives in micropropagation to enhance the growth and health protection of the explants could be tested.

CONCLUSION

This review provided a historical overview of the applications of in vitro cultivation of Zantedeschia and the phytopathological issues that limit the propagation of this ornamental crop. The establishment of Zantedeschia in the field free from pathogens is ensured using healthy in vitro propagated explants. In vitro culture has proven to be an effective tool for rapid clonal propagation and multiplication of Zantedeschia spp. However, the propagation in vitro of Z. aethiopica has faced challenges in some cultivars due to the contamination of the explants.

![Breaking of dormancy in hawthorn yam (Dioscorea rotundata[Poir.]) by applying plant growth regulators](/img/en/prev.gif)