Introduction

The search for products that are active against insect pests has been the focus of several works aimed at finding alternatives to commercial synthetic pesticides, which may become ineffective against many insects and cause a variety of adverse effects to the environment. This problem can be illustrated by the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith, 1797) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), which is a polyphagous insect that causes damage to many important crops in America. Historically, chemical control is the most common method employed to control this insect (Rosa and Barcelos 2012); however, there have been numerous reports on the appearance of populations that are resistant to insecticides (Yu 2006). More recently, genetically modified plants that express Bacillus thuringiensis toxins have been employed for S. frugiperda control, but there have been reports of resistant populations in the field (Vélez et al. 2016). This scenario is further aggravated by evidence of multiple/cross resistance to Bt and organophosphate insecticides in field populations of S. frugiperda (Zhu et al. 2015).

In this sense, plant secondary metabolites may be used as extracts by organic farmers (Isman 2008) or can serve as lead molecules (Zhao et al. 2016) for the production of new synthetic insecticides. Despite the recognized insecticidal activity of these substances, few products have been commercialized in the form of extracts or oils, and neem, Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae), is currently the most widely used. Commonly employed due to its multiple modes of action in insects; it may present toxicity due to the effects of antifeedants, deterrents and growth regulators (Gahukar 2016). Despite the great potential of secondary metabolites and the numerous reports of insecticidal activity, there are some obstacles concerning their use, being possible to mention mainly problems related to manufacturing, production costs, regulatory hurdles and the existence of chemotypes (Miresmailli and Isman 2014; Isman 2017). However, due to the greater concern over issues related to the environment and human health, an incentive to commercialize botanical insecticides has been observed. Estimates have been released that by 2025, botanical insecticides will compose up to 7 % of the biopesticide market globally (Isman 2015).

Among the classes of secondary metabolites produced by plants that exhibit insecticidal activity, phenolic compounds, alkaloids and terpenes can be highlighted (Chowański et al. 2016; Marques et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016). Therefore, substances derived from the metabolism of plants are very promising for insect control, since they can be lethal to insects or even cause sublethal effects. In the search for botanical insecticides, bioassays are usually conducted, with the evaluation of survival, duration of the larval and pupal periods, pupal weight, fertility, fecundity, etc. Recently, the effects of enzyme inhibitors against insect pests have also been explored, since this allows the development of insecticides with different modes of action and minor toxicity to non-target organisms (Jadhav et al. 2016; Swathi et al. 2016).

In view of the potential of plants in the development of new insecticides, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of extracts from Actinostemon concolor (Spreng.) Müll. Arg. (Euphorbiaceae), Geonoma schottiana Mart. (Arecaceae), Rudgea viburnoides (Cham.) Benth. (Rubiaceae) and Palicourea rigida Kunth. (Rubiaceae) on the biological, biochemical, and ultrastructural characteristics of S. frugiperda. These plants were selected because they are abundant in the Brazilian territory and belong to botanical families with recognized insecticidal activity against S. frugiperda (Tavares et al. 2013; Carvalho et al. 2015; Dos Santos et al. 2016). In addition, another criterion employed was the lack of studies of biological activity involving these species in the literature.

Materials and methods

Extract preparation

The leaves of A. concolor, G. schottiana, R. viburnoides and P. rigida were collected in Lavras, Minas Gerais, Brazil (21°14’43”S 44º59’59”W), oven-dried at 40 °C for 48 hours and subjected to trituration on a Wiley-type laboratory mill. Each dried and ground botanical sample (100 g) was immersed in methanol (Vetec) (500 mL) for 48 hours, resulting in mixtures that were filtered through cotton-wool plugs. The botanical material underwent 10 more extractions with 500 mL of methanol in each one. The products from the successive extractions were combined, concentrated to dryness in a rotary evaporator and then freeze-dried, giving rise to the plant extracts.

Insects

Laboratory-reared caterpillars of S. frugiperda were fed on artificial diet (Parra 2001), while adults were fed on aqueous 10 % (mL mL-1) honey solution. The laboratory-reared insects were maintained in a climatic chamber at 25 ± 2 °C and RH 70 ± 10 % and under a photoperiod of 14:10 (L:D). These conditions were also used in the experiments. Under these conditions, the life-cycle duration is approximately 50 days. Only those individuals from the second posture and of each generation were used in the experiments (Botton et al. 1998).

Effects on the biology of S. frugiperda

Solutions of the plant extracts (300 mg) in an aqueous 0.01 g mL-1 Tween 80® solution (30 mL) were prepared and added to 300 mL of the artificial diet (Parra 2001), which was then cut into pieces (2.5 × 2.0 cm). Each of these pieces was placed into a 50 mL plastic box containing one newly hatched caterpillar (1st instar). The experimental design was completely randomized, with six replicates per treatment; each plot consisted of six caterpillars that were maintained individually, totalling 36 insects per treatment, and the experiment was conducted twice. Two controls were used: water (30 mL) and aqueous 0.01 g mL-1 Tween 80® solution (30 mL). The biological characteristics evaluated were larval survival [(number of live caterpillars/total number of insects)*100], pupal weight (24 hours after pupation), larval and pupal period durations, pupal survival and sex ratio (number of females/total number of specimens).

After the emergence of adults, couples of S. frugiperda were isolated in cages for the daily observation of adult longevity, fecundity, fertility, and preoviposition and oviposition periods. The experiment was conducted in a randomized design with five replicates per treatment, with each replicate consisting of a couple. Those eggs from the second day of posture of each couple were used to determine their viability (estimated by counting the number of emerging larvae), while the eggs from the third day of posture were observed under a scanning electron microscope to evaluate the ultrastructure. For this, the samples were processed following the standard protocol for biological samples (Alves 2004). Images were observed under a Leo Evo 40 scanning electron microscope using the Leo User Interface.

Effects on the protein digestibility of S. frugiperda

This experiment was set up as previously described, except that the diet was weighed before being offered to S. frugiperda. Samples of the diets were maintained under the same conditions as in the experiment to estimate the water loss. After 10 days, the remaining diet, larvae and faeces were weighed. Then, all faeces, as well as aliquots of the diet not consumed by the insects, underwent freeze drying and protein extraction (Ferreira et al. 2008), which was followed by protein quantification (Bradford 1976). Briefly, aliquots (10 mg) of the samples (diets or faeces) were added to 200 µL type I water, and the resulting mixtures were shaken for 60 seconds in a vortex. Then, the mixtures were centrifuged at 818 × g, and 20 µL of each supernatant was diluted with 80 µL of type I water and added to 2 mL of Bradford reagent (containing Coomassie Blue, Merck). Absorbance was then measured at 595 nm [Visible Spectrophotometer (SP-1105), Shanghai Spectrum Instruments Co., Ltd.]. Values were converted into mass of protein by comparison with an analytical curve built using bovine serum albumin (Inlab) at concentrations ranging from 2 to 20 μg mL-1. Three replicates were employed for the protein quantification, which was carried out in duplicate. The protein digestibility (PD) was calculated using the formula PD (%) = [(ingested proteins - excreted proteins) × 100]/ ingested proteins. Ingested proteins = content of protein in the diet (μg mg-1) × food consumption (mg). Excreted proteins = content of protein in the faeces (μg mg-1) × weight of the excreted faeces (mg).

Determination of trypsin inhibitory activity by the A. concolor extract

The extract from A. concolor was employed in further bioassays since it showed bioactivity against S. frugiperda. Following the methodology of Oppert et al. (2005), 4th instar caterpillars of S. frugiperda were immobilized on ice to allow the removal of the anterior and posterior ends. Two intestines were then homogenized in 8 mL of distilled water at 4 °C. The resulting mixtures were filtered through nylon membranes with 100 μm pores (Whatman) and centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant liquids, which corresponded to the enzyme extracts, were immediately used in tests of trypsin inhibition that were carried out by measuring the residual enzyme activity towards the substrate benzoyl-DL-arginine-p-nitroanilide (BAPNA) (Sigma Aldrich) (Erlanger et al. 1961; Kakade 1974) in an experiment conducted in a randomized design with four replicates and four periods of time. The treatments consisted of the A. concolor extract (200 μL) at 25, 50, 100, 200 and 250 μg mL-1 in methanol. The control test was performed without inhibitor to occur at full speed. The reactions proceeded in the absence or presence of plant extracts, enzyme extract of S. frugiperda and substrate. The enzyme extract (200 μL) was added to the methanol solution of A. concolor extract (200 μL). Then, BAPNA (800 µL) at 0.87 mmol L-1 in DMSO [dimethyl sulfoxide (Synth) containing Gly (Merck)-NaOH (Vetec) buffer at 0.1 mol L-1 (pH 9.7)] was added to each reaction mixture. After 30, 60, 90 or 120 minutes at 30 °C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 200 µL of an aqueous 30 % (v v-1) acetic acid solution. The results are expressed as the percentage of trypsin inhibition.

Quantification of phenolic compounds

Aliquots (150 mg) of dry plant extracts were added in triplicate to 7.5 mL of a methanol:water (1:1) solution contained in round-bottom flasks, resulting in mixtures that were heated to reflux for 15 minutes. After cooling to room temperature, the mixtures were filtered, and the residues underwent two more hot extractions with methanol:water. The three filtrates from each aliquot were combined and poured into a 25 mL volumetric flask whose volume was filled to 25 mL with distilled water for the determination of total phenols by the Folin-Denis method (Association of Official Analytical Chemists 1960). Thus, 100 µL of Folin-Denis reagent [2.5 g sodium tungstate dihydrate (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5 g fosfomolibdic acid (Vetec), 1.25 mL phosphoric acid (Vetec), and water to complete the volume to 25 mL], 200 µL of saturated sodium carbonate (Êxodo) solution and 1.98 mL of water were added to triplicate aliquots (20 µL) of each resulting solution. Absorbances measured at 720 nm [Visible Spectrophotometer (SP-1105), Shanghai Spectrum Instruments Co., Ltd.] were converted into total phenol concentrations by comparison with an analytical curve built by the use of aqueous gallic acid (Sigma Aldrich) solutions at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 µg mL-1. The residue from methanol/water extraction of A. concolor methanolic extract was concentrated in a rotary evaporator and freeze dried and later bioassayed on S. frugiperda. The extraction yield [(mass of crude extract)/(mass of the residue from methanol/water extraction)] was 53.3 %.

Effect of the residue from methanol/water extraction of A. concolor on the biology of S. frugiperda

The residues of the methanol:water extraction of A. concolor were employed in this bioassay. The dry residue (192 mg) was dissolved in an aqueous 0.01 g mL-1 Tween 80® solution (30 mL) and incorporated into the artificial diet (300 mL). The resulting diet was weighed and offered to first instar S. frugiperda caterpillars according to the method described above. The experimental design was completely randomized, with six replicates per treatment and each plot composed of six caterpillars that were maintained individually. Survival in the larval and pupal stages, pupal weight, duration of the larval and pupal stages, and adult sex ratio were also evaluated.

Data analysis

Except for the values obtained in the trypsin inhibition test, which underwent the F test and regression analysis, all data that passed the normality test of Shapiro-Wilk were submitted to analysis of variance and comparison of means according to the Tukey test (Silva 2010). The R® software (R Development Core Team 2014) was used to carry out these calculations.

Results and discussion

Effects of the extracts on the biology of S. frugiperda

The extract of A. concolor reduced S. frugiperda survival during the larval stage and the weight of pupae. Furthermore, this extract also prolonged the larval and pupal stages of the insect (Table 1). The reduction in weight often correlated with a lengthening of the immature stages, which is indicative of the presence of substances affecting insect metabolism (Pereira et al. 2002). Adults that originated from larvae fed on diets containing the extract from A. concolor showed a reduction in fecundity and the viability of eggs (Table 1), which may be consequences of the reduction in the growth of insects during the immature stages caused by inadequate assimilation of nutrients in the larval stage. Similar behaviour was observed when Spodoptera littoralis Boisduval (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) ingested azadirachtin, which is produced by neem, A. indica (Pineda et al. 2009). The authors attributed the reduced fertility and fecundity to the interference of this substance in the metabolism of the insect, since it is known that the maturation of eggs in insects is dependent on nutrients such as proteins, carbohydrates and lipids, which are required for embryogenesis.

Table 1 Effects of artificial diet containing extracts of Geonoma schottiana, Actinostemon concolor, Palicourea rigida, and Rudgea viburnoides on larval survival (%), pupal weight (mg), larval and pupal stage durations (days), number of eggs/female and egg viability (%) in Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Biological characteristic | Treatment a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. concolor | G. schottiana | P. rigida | R.viburnoides | Tween 80 ® | Water | |

| Larval survival | 63.9 ± 5.12 b | 72.2 ± 5.54 ab | 86.1 ± 6.65 ab | 69.4 ± 6.68 ab | 88.9 ± 12.61 a | 91.7 ± 3.73 a |

| Pupal weight | 217.2 ± 10.01 b | 286.3 ± 10.42 a | 297.1 ± 3.11 a | 296.4 ± 3.78 a | 288.7 ± 2.92 a | 293.8 ± 3.43 a |

| Duration of larval stage | 34.9 ± 0.74 a | 23.4 ± 0.44 b | 22.4 ± 0.24 b | 22.5 ± 0.33 b | 23.1 ± 0.39 b | 23.0 ± 0.42 b |

| Duration of pupal stage | 12.8 ± 0.33 a | 12.0 ± 0.38 ab | 11.4 ± 0.23 b | 11.9 ± 0.33 ab | 11.6 ± 0.20 ab | 11.8 ± 0.28 ab |

| Number of eggs/female | 826.3 ± 77.38 b | 1,162.2 ± 76.63 ab | 1,292.0 ± 63.56 a | 1,098.3 ± 138.53 ab | 1,410.2 ± 96.94 a | 1,399.6 ± 87.96 a |

| Egg viability | 61.5 ± 3.40 c | 81.4 ± 1.65 ab | 78.3 ± 5.49 ab | 72.7 ± 2.52 bc | 91.5 ± 2.39 a | 89.4 ± 2.58 a |

aMeans (± SE) followed by same letter, in each line, do not differ statistically according to the Tukey test (P < 0.05).

The variables sex ratio (F = 0.7282; df = 5; P = 0.6078; average from 0.45 to 0.66), pupal survival (F = 1.774; df = 5; P = 0.3433; average from 80.0 % to 97.2 %), preoviposition period (F = 0.7720; df = 5; P = 0.5806; average from 3.6 to 4.5 days), oviposition period (F = 0.1590; df = 5; P = 1.7877; average from 5.5 to 8.0 days), and longevity of males (F = 0.2106; df = 5; P = 1.5743; average from 12.0 to 15.0 days) and females (F = 0.1487; df = 5; P = 1.8386; average from 9.8 to 13.0 days) were not affected by the treatments.

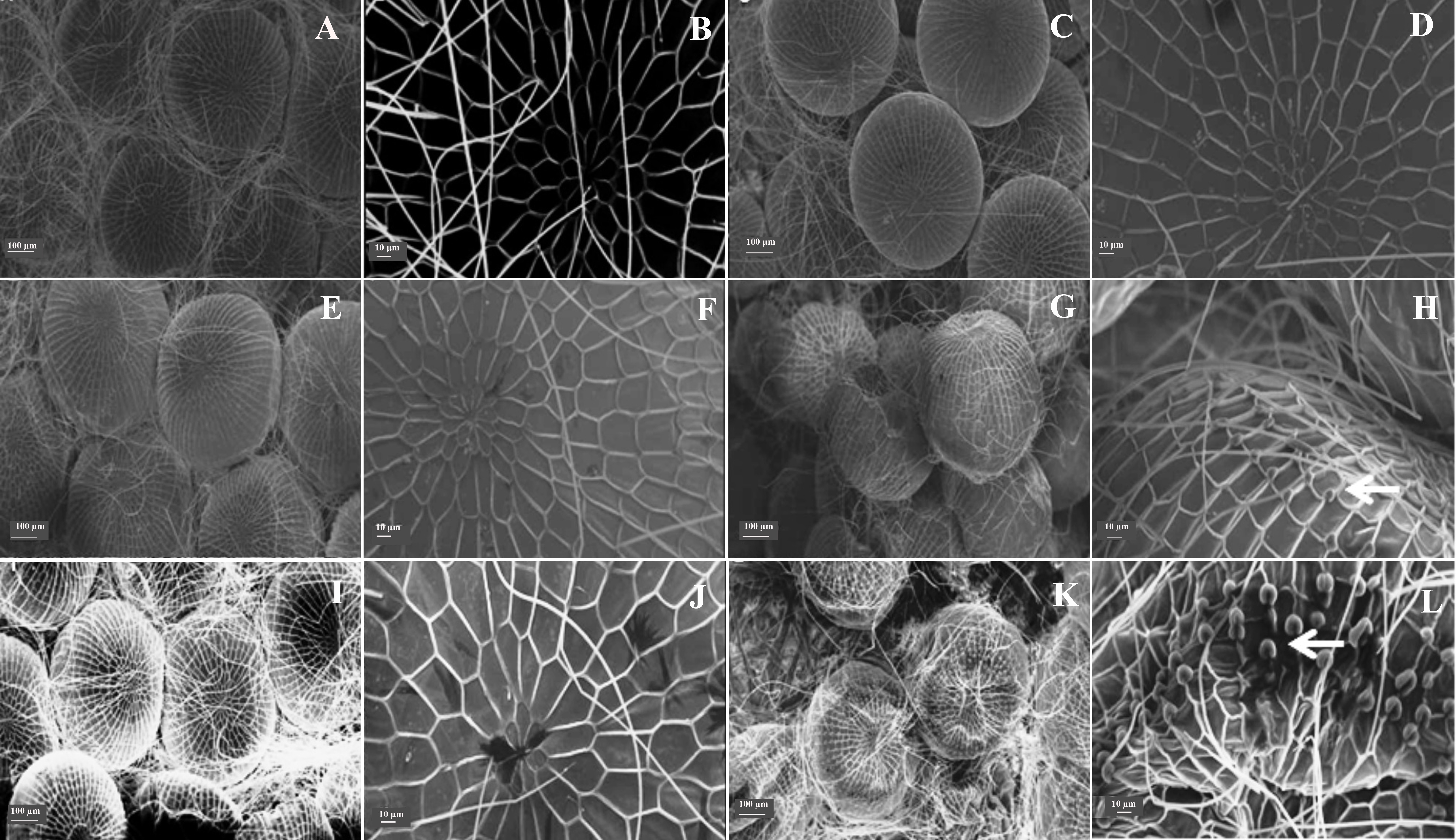

Eggs of insects fed with diets containing A. concolor and R. viburnoides extracts showed abnormal material deposition in the chorion (Fig. 1), which may account for their low viability. A similar effect on the embryogenesis of Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) has been reported with other products by other authors, who attributed such malformations to the ability of these products to affect the metabolism of lipids and proteins, which are major constituents of the chorion layer (Fila et al. 2002; Adamski et al. 2005).

Figure 1 Ultrastructural analysis of eggs of Spodoptera frugiperda that originated from caterpillars fed diets containing plant extracts. A and B. Water. C and D. Tween 80® aqueous solution. E and F. Palicourea rigida. G and H. Rudgea viburnoides. I and J Geonoma schottiana. L and M. Actinostemon concolor (arrows indicate malformations).

Effect on the protein digestibility of S. frugiperda

The A. concolor extract resulted in high digestibility values (Table 2). Perhaps S. frugiperda have maximized the digestion of proteins as a compensatory mechanism for the inadequate absorption of nutrients. These results seem to be in accordance with a report by Pilon et al. (2006), who found that the intake of the synthetic trypsin inhibitor benzamidine by Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) resulted in an increase in protein digestibility in this insect. However, in the present study, the caterpillars showed a 50 % reduction in weight gain despite the increased protein digestibility. It has also been found that protein digestion in the midgut of insects is not eliminated by inhibitors of proteases, since insects can usually overproduce these enzymes (Burgess et al. 2002). However, the high production of proteases negatively affects the availability of amino acids that are essential for the synthesis of other proteins, thus reducing the growth and development of insects (Murdock and Shade 2002; Oppert et al. 2005).

Table 2 Effects of the extracts from Rudgea viburnoides, Palicourea rigida, Geonoma schottiana and Actinostemon concolor on protein digestibility (PD) (%) of Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Treatment | PD (%) a |

|---|---|

| Actinostemon concolor | 97.1 ± 0.51 a |

| Geonoma schottiana | 88.7 ± 1.88 b |

| Palicourea rigida | 95.5 ± 0.59 a |

| Rudgea viburnoides | 88.4 ± 0.71 b |

| Water | 87.9 ± 1.58 b |

| Tween | 89.4 ± 1.11 b |

a Means (± SE) followed by same letter do not differ statistically according to the Tukey test (P < 0.05).

Determination of trypsin inhibitory activity by the A. concolor extract

In the 25 to 250 μg mL-1 range of concentrations, the extract of A. concolor inhibited 32.7 to 81.8 % of S. frugiperda trypsin activity (Fig. 2). Protease inhibitors are usually peptides or small proteins that play roles in the defence of plants against insects. These molecules act in the insect midgut, causing a reduction in the availability of amino acids necessary for growth and development (Leo et al. 2002). However, other classes of substances can cause similar effects, a good example being tannins, which can form complexes with the digestive enzymes of insects, reducing their activity in the gut (Klocke and Chan 1982). A disorder in the metabolism of proteins can be a disaster for insects, since it can alter parameters such as growth, nutrition, morphology and reproductive performance (Franco et al. 2003; Ramos et al. 2009).

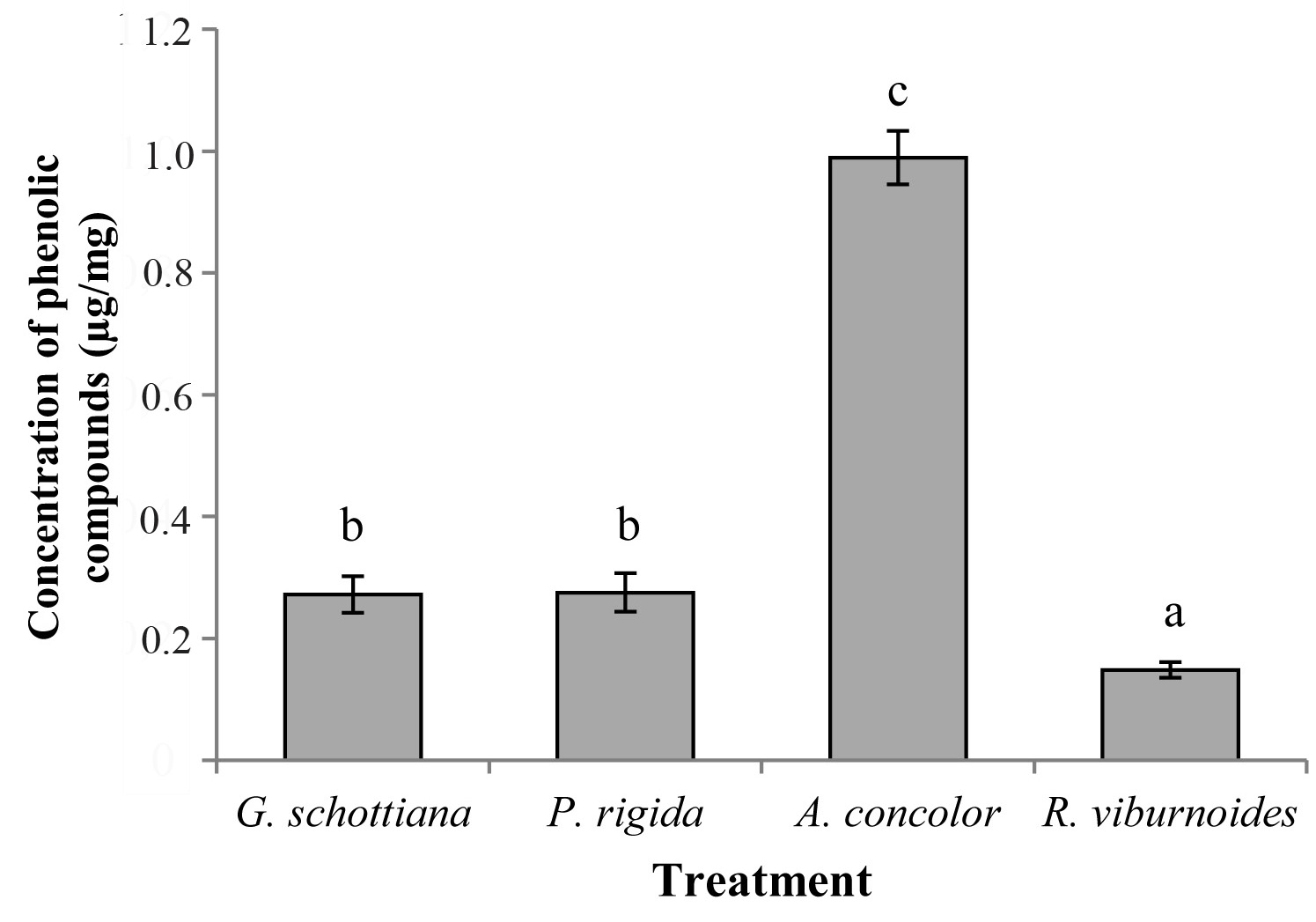

Quantification of phenolic compounds

The A. concolor extract showed concentrations that were about four times higher than those found in the other extracts (F = 1694.4; df = 3; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). Phytochemical studies on the species used in this work are scarce; however, plants in the family Euphorbiaceae, such as A. concolor, exhibit high levels of phenolic compounds, with Alchornea glandulosa Endl. & Poeppig (Euphorbiaceae) being an example (Calvo et al. 2007). Phenolic compounds may be related to the insecticidal activity of some plant species, being possible to mention that the insecticidal activity of Annona species against S. frugiperda has been correlated with the content of phenols (Freitas et al. 2014).

Figure 3 Means (± SD) of the concentrations of phenolic compounds in the extracts of Geonoma schottiana, Palicourea rigida, Actinostemon concolor and Rudgea viburnoides.

Secondary metabolites belonging to the class of phenolic compounds constitute one of the most common and widespread groups of chemicals related to plant defence against herbivory; these substances can either kill or retard the development of insects (War et al. 2012). The results found in this study are consistent with other reports in which a relationship between the content of total phenols and insecticidal activity was found.

Effect of the residue from methanol/water extraction of A. concolor on the biology of S. frugiperda

The residue from methanol/water extraction of A. concolor caused effects in S. frugiperda that were similar (Table 3) to those observed when the methanolic extract was offered to these insects (Table 1); this result indicates that methanol/water residue contains active substances against S. frugiperda. Due to the higher content of phenolic compounds in the A. concolor extract, it is possible to suggest that this class of substances may be related to insecticidal activity. These metabolites can act by reducing palatability or acting as inhibitors of digestion through the precipitation of dietary proteins or digestive enzymes (Bernays and Chamberlain 1980). However, it is possible that other substances present in small amounts are responsible for the bioactivity, thus more phytochemical studies are needed with the aim of isolating the active substance(s).

Table 3 Effects of the residue from methanol/water extraction of the Actinostemon concolor extract on caterpillar survival (%), pupal weight (g) and larval and pupal stage durations (days) in Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Biological characteristic a | A. concolor | Tween 80 ® | Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caterpillars survival | 44.4 ± 3.52 b | 80.0 ± 5.44 a | 88.8 ± 5.55 a |

| Pupal weight | 0.21 ± 0.01 b | 0.28 ± 0.004 a | 0.30 ± 0.007 a |

| Duration of larval stage | 28.8 ± 0.51 a | 20.7 ± 0.16 b | 20.0 ± 0.17 b |

| Duration of pupal stage | 11.2 ± 0.23 a | 9.9 ± 0.20 b | 9.4 ± 0.11 b |

a Means (± SE) followed by same letter, in each line, do not differ statistically according to the Tukey test (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The methanolic extracts of G. schottiana, R. viburnoides and P. rigida did not cause toxic effects on the larval, pupal or adult stages of S. frugiperda. The ultrastructural analysis of eggs from adults fed with R. viburnoides and A. concolor made it possible to visualize the abnormal deposition of material in the chorion. The highest toxicity to S. frugiperda caterpillars was observed when the methanolic extract of A. concolor or its residue of extraction methanol/water was employed. This extract increases the digestibility of proteins but inhibits trypsin, which reinforces the hypothesis that the probable mechanism of insecticidal action of A. concolor against S. frugiperda is due to the inhibition of insect proteases. The high content of phenolic compounds in A. concolor extract corroborate the hypothesis that these compounds may be responsible for the activity against S. frugiperda. In conclusion, A. concolor causes changes in the development, reproduction and nutrition of S. frugiperda.