1. Introduction

Reducing waste and cooperation between entities in the supply chain is a global concern (United Nations, 2018). This is the twelfth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of the United Nations (UN). However, we are still far from achieving these SDGs. According to the World Bank (2018), Chile is the second country that generates the most waste per capita in Latin America. Furthermore, according to growth estimates for ECLAC (2017), the consumption of raw materials by 2050 will be three times the current demand. Therefore, both challenges will generate more significant pressure on the environment (World Resources Institute, 2003; Franklin-Johnson, Figge, and Canning, 2016), which requires actions to achieve sustainable development for future generations.

One way to control the consumption of resources, reduce waste, and reduce negative impact on the environment is through sustainability strategies (Navarrete, 2015), Specifically Circular Economy (CE) strategies (Morseletto, 2020; Ferasso, Beliaeva, Kraus, Clauss, and Ribeiro‐Soriano, 2020; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015). Although CE has been applied in companies that make profit. For example, in e-commerce businesses or those carry out an engineering change (Alsaad, Mohamad, and Ismail, 2017; Lodgaard, Ringen, and Larsson, 2018), the evidence for nongovernmental organizations is limited. Nongovernmental organizations are characterized by the value they generate through their social achievements and charitable contributions (Moore, 2000). An example of this is the charity shop that, through the sale of donated products, obtains benefits destined to help others (Blume, 1995).

Specifically, in Chile, environmentally conscious consumers have been found whose concerns motivate donations to charity (Bianchi and Birtwistle, 2012). In fact, previous studies indicate that volunteers and the community itself are agents of change in CE (Dururu, Anderson, Bates, Montasser, and Tudor, 2015). In other words, the concern of various stakeholders to contribute to the welfare of society in a disinterested way is observed, which, in the words of Batson (2010), is a way of exhibiting altruistic behavior.

Although the interaction between stakeholders inside and outside organizations allows collaborative practices that promote the formation of business models for sustainability and CE (Mishra, Chiwenga, and Ali, 2019; Roome and Louche, 2016), there remain gaps to fill. On the one hand, Mhatre, Panchal, Singh, and Bibyan (2020), in their literature review invite us to explore the impact of stakeholder collaboration in CE, and on the other hand, nongovernmental organizations possess appropriate components for the implementation of a CE business model. However, little is known about the behavior of the different stakeholders who participate in a nongovernmental organization, specifically in a charity shop, which encourages CE practices. Therefore, the following question arises: How does the social behavior of stakeholders explain the implementation of CE business models in nongovernmental organizations?

To respond to this research question, the qualitative methodology of the case study is used through semi-structured interviews. To do this, we focus on the COANIQUEM charity shop in Chile. Furthermore, we base our work on stakeholder theory that indicates that to be successful, organizations must consider stakeholder expectations (Freeman, 1984). We also use the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to analyze the behavior of stakeholders in nongovernmental organizations that employs CE practices (Ajzen, 1991).

This study presents two contributions. First, we contribute to the CE literature in a nongovernmental organization context by focusing on the sustainable practices implemented by charity shops. Second, we extend the research regarding the TPB theory by deconstructing the attitude that explains the behavior of the various stakeholders of charity shops. This is achieved by providing new evidence for understanding by relating behavior to the CE strategies of the ReSOLVE framework, specifically, reusing, recycling, sharing, and looping. Also, this research has practical implications for nongovernmental organizations and professionals interested in incorporating CE practices. It is essential to consider the attitude of the stakeholders in the value chain.

1.1. Circular economy strategies (CE)

Circular strategies consider social benefits and improvements in environmental protection (Govindan and Hasanagic, 2018). This approach promotes continued economic development. Specifically, CE is defined as the permanent regeneration of the life cycle of a product, promoting the reduction of waste through recycling and reusing products and thereby generating both environmental and economic benefits (Ilić and Nikolić, 2016; Urbinati, Chiaroni, and Chiesa, 2017; Ferasso et al., 2020).

Then, through CE strategies, resource consumption and waste reduction are controlled as an integrated process encompassing the entire value chain (De Jesus, Antunes, Santos, and Mendonca, 2018). The implementation of CE in organizations is based on circular strategies based on the ReSOLVE framework: regenerate, share, optimize, loop, virtualize, and exchange. Regeneration refers to the actions of change of energy and renewable materials; sharing actions refer to the exchange of products between peers or the reuse of products (e.g., second hand); optimization actions focus on increasing performance, increasing the efficiency of a product, and eliminating waste in the production process and the supply chain; loop actions refer to the permanence of components and materials in closed systems; virtualization actions refer to the ease of delivering a good virtually; and exchange actions focus on replacing old materials with advanced nonrenewable materials and/or with new technologies (Morseletto 2020; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015).

Therefore, for organizations to implement circular strategies, two aspects must be considered. On the one hand, the recovery system considers the application of reverse logistics in the management of return, reuse, and collection of used products (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015). This implies that the products, components, and/or materials can be reused, remanufactured, or recycled (Mhatre et al., 2020; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015). On the other hand, when moving from a linear model to a circular one, internal and external issues in the organization must be considered. Internal ones refer to organizational capabilities, team motivation, organizational culture, knowledge, and transition procedures (Scott, 2015; Mentink, 2014; Laubscher and Marinelli, 2014). Conversely, the external ones are those elements that exert pressure on the organization but do not depend on it, such as technological, political, sociocultural, and economic issues (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015; Scott, 2015).

It should be noted then that CE can adopt a holistic view of the three dimensions of sustainability: environmental, social, and economic (Geissdoerfer, Savaget, Bocken, and Hultink, 2017; Elkington, 1997). The environmental perspective is related to issues such as resources, waste, and emissions; the economic perspective considers the benefits generated by reducing inputs and avoiding waste; finally, the social perspective is primarily associated with aspects of employment and lifestyles (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017).

1.2. Nongovernmental organization: charity shops

According to Moore (2000), nongover-nmental (or nonprofit) organizations are characterized by their social achievements and charitable contributions. These charitable actions toward various individuals who make up our society ultimately seek the well-being of others (other than their own well-being) as an end in itself; Batson (2010) calls this altruism. This altruistic behavior is part of the essence of these organizations. This altruistic behavior is not only present in the help or support of these organizations but also depends on the altruistic values of their stakeholders so that their work lasts over time.

Such is the relevance of the relationship with its stakeholders that there is literature that has placed these organizations at the center of multiple bilateral relationships with stakeholder groups (e.g., employees, consumers, or donors; Abzug and Webb, 1999). According to Ben-Ner and Van Hoomissen (1991), these organizations are founded and controlled mainly by stakeholders who demand these goods and services.

Specifically, a charity shop represents a bilateral relationship based on altruism between nonprofit organizations and various stakeholder groups. According to the charity commission, a charity shop is defined as “a shop that sells donated products whose profits are used for charitable purposes” (Blume, 1995, p. 18). Furthermore, they are recognized as future organizations responsible for recycling and reusing second-hand clothing (Parsons, 2002). Even in Chile, there are environmentally conscious consumers who act as motivators of donations to charity (Bianchi and Birtwistle, 2012). Furthermore, an environmentally conscious consumer environment tends to buy environmental-friendly products with a positive attitude toward second-hand products (Lim, Tim, Wong, and Khoo, 2012).

Therefore, to the extent that the sociocultural aspects are conducive to altruism, solidarity (of donors and sellers), and the reuse of products, it will be easier to explain the implementation of a CE strategy in charity shops and, consequently, interpret the social behavior of the stakeholders involved in these nongovernmental organizations.

Next, the theoretical perspectives of TPB and stakeholders are explained to understand the question posed by the literature.

1.3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The TPB derived from the theory of reasoned action considers the influence of personal determinants in predicting behavior at the individual level to collaborate in a charity shop with strategy of CE (Ajzen, 1991). In this theory, behavioral intention is determined by three primary factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, whose intention causes the behavior of a specific action. Then, the attitude toward the behavior to collaborate in a charity shop is explained as the mental state of the favorable (i.e., positive) or unfavorable (i.e., negative) evaluations of an individual to perform a specific behavior. The subjective norm is the perception of individuals about the social pressure to carry out behavior of collaborating in a charity shop. Perceived behavioral control focuses on internal capacities based on the individual’s perception of possible difficulties when collaborating in a charity shop (Ajzen, 1991).

The TPB model has been extensively used to explain human intentions to engage in particular behaviors, such as the direct relationship between TPB factors and behavioral intent to green practices (Echegaray and Hansstein, 2017; Oztekin, Teksöz, Pamuk, Sahin, and Kilic, 2017; Chen, 2016; Han, Hsu, and Sheu, 2010). For example, Echegaray and Hansstein (2017) use TPB to analyze the intention and behavior of consumers toward the recycling of the electronic waste in Brazil, proposing that the three constructs of TPB (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) significantly predict the intention to recycle. Chen (2016) studies the green loyalty to use public bicycles considering the attitude toward protecting the environment. On the contrary, Singh, Chakraborty, and Roy (2018) use the TPB to explored CE willingness in Indian companies; they found that two (attitude, subjective norm) of the three constructs of the TPB significantly predict the intention for the CE.

1.4. Stakeholder theory

This theoretical perspective recognizes that organizations are embedded in a network of relationships and interests with other actors. For Freeman (1984), the stakeholders are employees, buyers, sellers, and shareholders. According to this perspective, the decisions made by the companies are determined by the need to respond to the interests and demands of the multiple stakeholders; in return, the company obtains the resources needed for its operations (Harrison, Bosse, and Phillips, 2010).

Therefore, within this perspective, organizations must adequately address stakeholder expectations originating from both the internal and external environment, as a precondition for long-term success. This is consistent with what was stated by Roome and Louche (2016), who indicate that new business models for sustainability are created on the interaction between individuals and groups that are inside and outside organizations. In fact, the collaborative role of stakeholders throughout the supply chain enables the transition to CE in a developing country (Mishra et al., 2019). Gupta, Chen, Hazen, Kaur, and González (2019) argued for big data analysis from the stakeholder perspective that a collaborative partnership between all supply chain members can positively affect the implementation of CE. Thus, for charity shops, the internal stakeholders are the nongovernmental organization itself where the managers and workers are located. Conversely, external stakeholders are donors and consumers.

In this context, stakeholder expectations can be understood on a moral basis (Vazquez-Brust, Liston-Heyes, Plaza-Úbeda, and Burgos-Jiménez, 2010); therefore, organizations must generate profits, but they also have social and environmental responsibilities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research design

Based on a qualitative methodology, the case study approach is used because it is suitable for investigating phenomena in the context of real-life (Yin, 2003; Hartley, 2004). This approach is important because the phenomenon of sustainability is context-dependent. The case study provides in-depth data to generate new ideas and complete descriptions from various sources (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007).

2.2. Selected case

For this study, the nongovernmental organization COANIQUEM was chosen because it incorporates charity shops into its business model, reflecting a transformative change in the way in which resources are generated to finance its activities through CE strategies, thus involving various stakeholders.

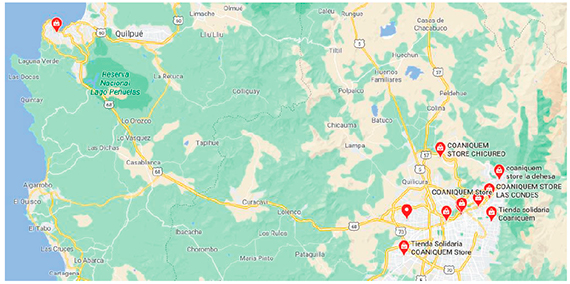

COANIQUEM is a private Chilean nongovernmental organization whose purpose is to rehabilitate children and adolescents with burns comprehensively and freely, prevent, train, and investigate this pathology. To do this, they act together with their families, network of complements, and society. Since 1994, COANIQUEM, as a way of raising funds, began to develop practices for sustainability with the glass recycling campaign, recovering on average more than 10 thousand tons/year. Since 2017 and as an example of international corporations, COANIQUEM has implemented 16 charity shops between the Valparaíso region and Santiago de Chile. In Figure 1, the geographical location of each store and their details are displayed in Table 1.

Source: Google maps, 2020. https://bit.ly/3i3nS3W

Figure 1 Geographical location of the COANIQUEM charity shops

Table 1 Description of COANIQUEM charity shop

| Location | COANIQUEM Charity shop | Business hour | Donations received | Donations not received |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santiago de Chile, Chile | Apumanque | In general, they open at 10 am and close at 8 pm. | Donations of clothing and use items that can be given a second life are received, such a clothes, shoes, accessories, books, CDs and movies, home décor items, furniture, appliances, toys and wheels, all clean, working and in perfect condition. | Pajamas and underwear are not accepted. For safety reasons, mattresses, electric ovens, microwaves, kettles or stoves are also not received. |

| Chicureo | ||||

| Estado | ||||

| Providencia | ||||

| Estación Central | ||||

| Las Condes | ||||

| La Dehesa | ||||

| La Reina | ||||

| Vitacura | ||||

| La Florida | ||||

| San Bernardo | ||||

| Ripley Alto Las Condes | ||||

| Ripley Parque Arauco | ||||

| Ripley Plaza Egaña | ||||

| Ripley Costanera | ||||

| Region of Valparaíso, Chile | Valparaíso |

Source: Own elaboration based on information on the website COANIQUEM, S.f.

The COANIQUEM charity shops are supplied by donations made by people (clothes, furniture, ornaments, shoes, and books), which are offered to the community at a low price. Furthermore, the stores are staffed by vendors and/or volunteers from the organization. Under this model, COANIQUEM encourages helping children with burns and caring for the environment by contributing to the reuse of all kinds of items.

2.3. Data source

The case was developed from primary and secondary sources to achieve the data triangulation process (Eisenhardt, 1989). Secondary data collection was carried out on the websites, reports, and newspaper news about COANIQUEM charity shops. The primary data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews. Some of these interviews were conducted in person (face to face); however, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing, other interviews were conducted by telephone during the period of September 2019 and November 2020. The interviews were carried out with 12 stakeholders (e.g., in the study by Gupta et al. (2019), they use 10 stakeholders) in a sample of selection by convenience. The stakeholders interviewed were: store manager (1), sales assistants (2), donors (3), and buyers (6), with an interview duration of approximately 20-30 minutes. The structure of the interviews consisted of presenting the topic of discussion to the interviewees, obtaining their informed consent, and then asking introductory, general, and in-depth questions. For example, the following questions were asked: What are your age and profession? (preliminary questions), How did you come to buy in the COANIQUEM charity shops? How did you find out about the COANIQUEM charity shops? Can you tell me your story? (general questions for the buyer) What is the most beneficial or positive thing you find of being a donor in the COANIQUEM charity shops? (an in-depth question for the donor). Each of the interviews was recorded and transcribed by the researchers for further analysis. Details of the interviewees can be found in Table 2. Moreover, in-person visits were made to the COANIQUEM charity shops located in Valparaíso and Santiago de Chile. These visits were aimed at being able to observe the activities carried out by the different stakeholders within the stores. The observation allowed to have a better understanding of the phenomenon under analysis.

Table 2 Interviewees of the study CE-COANIQUEM charity shop

| Gender | Age | Stakeholder-role in the shop | Interview mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Female | 40 years | Manager | Face-to-face |

| P2 | Female | 26 years | Buyer | Face-to-face |

| P3 | Male | 20 years | Buyer | Face-to-face |

| P4 | Female | 34 years | Sales assistant | Telephone |

| P5 | Female | 22 years | Buyer | Telephone |

| P6 | Male | 25 years | Buyer | Telephone |

| P7 | Female | 25 years | Buyer/Donor | Telephone |

| P8 | Male | 20 years | Buyer | Telephone |

| P9 | Female | 36 years | Sales assistant | Telephone |

| P10 | Female | 20 years | Donor | Telephone |

| P11 | Female | 32 years | Buyer/Donor | Telephone |

| P12 | Female | 19 years | Buyer/Donor | Telephone |

Interviews conducted during the period September 2019 - November 2020.

2.4. Analysis of data

Once the data was obtained from the respective sources, the information triangulation process was performed according to the literature on the phenomenon (Threlfall, 1999). For this, the information obtained from the interviews with donors, buyers, sales assistants, and a manager of the COANIQUEM store were analyzed and interpreted, through an analytical process determining categories, relationships, and assumptions. Spiggle (1994) points out that these inferences are used to generate conclusions with the theory. This analytical process consists of several stages, from a higher to a lower level of generality, which allows a circular analysis to develop conclusions and generate or confirm the theory. First, to obtain greater generality and determine the primary categories, we rely on the NVivo software to determine the frequency of words (Figure 2). In this way, we observe various general categories that arise from the words most highlighted by the various stakeholders, for example, donate, buy, clothes, help, recycle, and cheap (low price). Second, more specifically, we associate the content of each category to the TPB and stakeholder theories to understand the behavior of each actor. Finally, the results are analyzed to generate the discussion and conclusions.

3. Results and Discussions

The data reveal that one of the causes that leads to a behavior of working, donating, or buying by the stakeholders (by the manager, sales assistants, donors, or buyers, respectively) in COANIQUEM charity shops is due, in the first place, to the attitude of the stakeholders. According to the data analysis and the attitude construct, it can be differentiated in the environmental attitude, social attitude, and economic attitude. To clarify what has been indicated, below, we present examples of our interviewees’ responses, both internal stakeholders classified as sales assistants and managers and external stakeholders classified as buyers and donors.

Regarding the environmental attitude, it can be identified that the stakeholders have a favorable position (i.e., positive) for the protection of the environment (Chen, 2016; Echegaray and Hansstein, 2017; Oztekin et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2018). Internal stakeholders, such as the sales assistant P4, indicate that working in charity shops that implement CE strategies has encouraged them to be more environmentally conscious.

“To be super honest, I recycle now that I’m working here […] Before I didn’t worry much, I just got into recycling plastic bottles and suddenly I was going to leave the glass bottles to the bells that were in the supermarkets, but now yes, obviously I care and I am more aware of recycling, and you realize, for example, that the things you sell can give you a second or third useful life, and I consider it super important” (P4/ sales assistant).

Similarly, manager P1 indicates that the COANIQUEM charity shops reduce the carbon footprint, promote recycling, and demonstrate an environmentalist disposition.

“Well, the best thing about the stores anyway is the social contribution they make because it is in line with what is happening in the world today, we are saving carbon footprint because the donation is from “my neighbor” is not something that traveled thousands of kilometers to get there, it is also the whole issue of recycling, that is, everything that is on it can have a second life that is wonderful, then the other good things it has are sustained right there” (P1/ manager).

Concerning external stakeholders, buyer P5 compares the store with the retail industry, indicating the level of contamination that these generate so that their behavior as a buyer in the store would be affected by these high rates.

“Mainly you are helping the foundation and you are also reusing clothes, which we already know: retail or stores that sell in masses are very polluting, so you are also helping the environment and at the same time a foundation, very beautiful so the rest” (P5/ buyer).

Conversely, donor P10 indicates that his environmental attitude is related to his willingness to reuse clothing more.

“That clothes are not thrown away because if you have something small you don’t have to throw it away, if not you can give it a double use, in the end, it is much better than buying at the mall […] It represents a change in thinking, of that people are looking for alternatives to be able to recycle, to give more use to clothes or other things, because in the end, if you buy something and throw it away later because you don’t like it or don’t know what it is like, it is wasted and accumulates, you are damaging the environment” (P10/ donor).

Regarding the social attitude, it can be identified that the stakeholders have a favorable position due to the social aspects and values that the COANIQUEM charity shop delivers. Like other studies, the contribution to the well-being of society is selflessly recognized (e.g., Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). Internal stakeholders, such as sales assistants P4 and P9, indicate that working in the store causes them a feeling of contribution toward society, on the one hand, because their functions support children and, on the other hand, because it makes them more human work helping other people.

“It is the end, you know that you are doing a job for the children, that you are helping with your contribution, whether it be serving people, cleaning the store, ordering, choosing the best clothes, you are contributing, you feel a contribution towards the society, I always say: the beauty of this work is that it has a meaning” (P4/ sales assistant).

“Knowing about this work, becoming more human by working to help other people, that just makes you great; it makes you get involved with your heart because you already know closely what happens, that children get burned […] I really feel very grateful for being in this place and knowing the foundation” (P9/ sales assistant).

External stakeholders, such as the buyer and donor P7, indicate that collaborating in the COANIQUEM store generates a feeling of solidarity for the fact that they are helping, which leads to an attitude of solidarity.

“[…] I only went to the COANIQUEM store to get rid of things at first, but later on you are generating a feeling for the fact that you are helping, then it is an evolution of the attitude that you do not realize: you start with something relatively material and you went to a solidarity action; so I think that going through that experience is elementary. You also have to be super aware that what you are doing is a donation; you are not throwing away garbage, because there are people who are going to buy it, regardless of why” (P7/ buyer and donor).

Furthermore, according to the buyer P1, indicates an attitude of cooperation with the cause.

“The first time I visited the store, I was curious to see how this system worked, keeping in mind the intention of cooperating with the cause. I was motivated to buy the fact of finding clothes and articles from a very good selection” (P1/ buyer).

Regarding the economic attitude, it can be identified that the stakeholders present a positive trend both in the economic aspect and well-being (e.g., Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2012). According to manager P1 (internal stakeholder), the organization’s attitude oriented to the economic thing refers to the innovative way that it has to raise funds.

“The wonderful thing it has is the way of raising funds, the objective of this is a palpable thing, you see that child who has a wound in his little hand and thanks to this I get rid of something that I have in my house, this also has something positive in people, that is, letting go of all of us does us good. So, you let go of this that does not serve you, I am going to throw it away, but instead of going to the landfill this goes to a second life, and that second life also generates a child to heal because COANIQUEM attends 100% free to all its patients, it does not charge money, and it also gives accommodation to those who come from abroad” (P1/ manager).

According to external stakeholders, the buyer P6 indicates that the economic attitude is related to the price of the clothes and the action of helping others.

“I think it is a good way to help, for both sides, to help customers because clothes are cheap, to help the environment because clothes are being reused, and to help the people of COANIQUEM” (P6/ buyer).

Furthermore, buyer P3 confirms that the store has an essential role in the community.

“I think they have a super important role; I also think they are pioneers in this system of joining a foundation in a more direct way with the community: anyone can go to donate, anyone can go shopping, they have a Redcompra system, I feel that everything is very accessible, and I think more companies should join, more foundations, implement more things like that, and COANIQUEM has clothes, has home accessories, things like that” (P3/ buyer).

For those stakeholders who are buyers and donors, the interviewee P12 indicates that it is convenient for both those who donate and those who buy since the purchase value is low, and meanwhile, it is gratifying to be able to help the people in need.

“For me, it is super good because it suits both those who donate and those who buy, the clothes are very cheap, there are good clothes” (P12/ buyer and donor).

Even the interviewee P11 indicates that besides the low price, the clothes are pretty good.

“[…] the truth is that one finds quite good clothes, very cheap and I, really, 70% of my closet is from COANIQUEM” (P11/ buyer and donor).

As our findings show, not all the constructs of the model proposed by the TPB theory have the same preponderance. The presence of the subjective norm and perceived control is unobservable. On the contrary, the attitude construct is relevant as an antecedent of the behavior of the stakeholders in the charity shop. Furthermore, when analyzing the data, we observe the relationship between stakeholders and their behavior (as indicated by Roome and Louche, 2016). In the first place, interviewer P11 explains how the role in front of the store is changing, from buyer to donor, demonstrating his positive attitude toward the role that the COANIQUEM charity shop performs in the community. This is mainly due to the generation of awareness about recycling, the textile industry, and helping.

“The truth is that I started buying and later I realized that it could be donated and, the truth is that I have to use the clothes again, so that’s basically a little help and recycle […] Go a little further to create a little more awareness about recycling clothes because the textile industry is really very polluting; and you really find things that are practically unused in those stores and that obviously deserve to have a second life” (P11/ buyer and donor).

Conversely, stakeholders see the role of the foundation’s volunteers in charity shops positively. For example, P12, who is an external stakeholder, perceives the role of volunteers as favorably as P3.

“[…] The volunteers are super nice, you can see that they are super committed, they are very dedicated to what COANIQUEM means” (P12/ buyer and donor).

“I think the care is super good because, for example, I have had some supervisors who are organizing everything, but the volunteers are helping you find things or guiding you in what you are looking for, they have very goodwill and, to be volunteers, they do it motivated, not looking for a material good or remuneration, but they do it from what they feel, their values” (P3/ buyer).

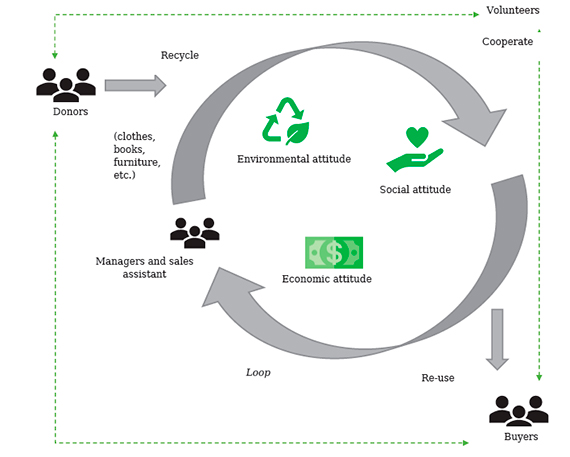

Thus, Figure 3 summarizes the results of the study, connecting the CE and the charity shop based on the theories of TPB and stakeholder theory. The sustainable attitude of internal and external stakeholders be it environmental, social, or economic, leads them to an intention and then to the social behavior to donate, buy, share, or work in these nonprofit organizations. Behavior that makes circular strategies to reuse, recycle, share, and close the cycle (loop) is visible based on the ReSOLVE framework.

Figure 4 graphically explains the social behavior of the different stakeholders (internal and external) in a nongovernmental organization that carries out CE strategies. Stakeholders’ conduct that denotes an environmental, social, and economic concern promotes the development of CE strategies of the COANIQUEM charity shop.

Source: Based on study findings and framed in the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015) CE business model

Figure 4 CE-stakeholders study result model from COANIQUEM charity shop

4. Conclusions

This study contributes to the CE literature in a nongovernmental organization context by incorporating a CE business model.

We propose that the interaction between stakeholders (inside and outside the organization) not only promotes actions that protect the environment through circular strategies based on the ReSOLVE framework, such as recycling, reusing, and sharing, but also induces solidarity and economic actions through donations and the purchase of products offered by the store. This leads to the formation of resources that helps children who are users of the COANIQUEM foundation.

In other words, implementing CE models in a nongovernmental organization is expected to contribute to sustainable development, which is understood as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987), indicating that environmental, social, and economic aspects reinforce each other and act as interdependent pillars (UN General Assembly, 2005).

Therefore, according to our findings, CE would allow a holistic view of the three dimensions of sustainability: environmental, social, and economic (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Elkington, 1997) in a nongovernmental organization.

Our work illuminates how nongovernmental organizations contribute to the CE paradigm. The COANIQUEM stores rethought and redesigned the way to obtain resources to continue being in solidarity. In this model, the different stakeholders’ interaction and collaboration are relevant, who generate behaviors of donating, buying, or working in charity shops, thanks to their environmental, social, and economic attitude in this context.

The limitations of this research are related to the stakeholders participating in the study, recommending the incorporation of volunteers from the organization and government representatives in future research. Furthermore, we recommend continuing to delve into the context of nongovernmental organizations, answering new questions that, through a quantitative approach, allow identifying, describing, or valuing the relationship between the interaction of stakeholders and CE strategies.