Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Investigación y Educación en Enfermería

Print version ISSN 0120-5307

Invest. educ. enferm vol.32 no.1 Medellín Jan./Apr. 2014

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL ARTICLE / ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Continuing education in nursing as a factor associated with knowledge on breastfeeding

Formación continuada en enfermería como un factor asociado al conocimiento en lactancia materna

Formação continuada na enfermagem como um fator associado ao conhecimento em aleitamento materno

Mariana de Oliveira Fonseca-Machado1; Vanderlei José Haas2; Juliana Cristina dos Santos Monteiro3; Flávia Gomes-Sponholz4

1RN, Master. Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. email: mafonseca.machado@gmail.com.

2Physicist. PhD. Professor Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG, Brazil. email: haas@vjhaas.com.

3RN, PhD. Professor Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. email: jumonte@eerp.usp.br.

4RN, PhD. Professor Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. email: flagomes@eerp.usp.br.

Receipt date: Aug 13, 2013. Approval date: Feb 10, 2014

Article linked to research: Conhecimento e práticas de profissionais de enfermagem das equipes de saúde da família, de um município do interior de Minas Gerais, sobre promoção ao aleitamento materno.

Subventions: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Conflicts of interest: none.

How to cite this article: Fonseca-Machado MO, Haas VJ, Monteiro JCS, Gomes-Sponholz F. Continuing education in nursing as a factor associated with knowledge on breastfeeding. Invest Educ Enferm. 2014;32(1): 139-147

ABSTRACT

Objective. Identifying the knowledge about breastfeeding of the nurses of the Family Health Program, and possible associations between the knowledge and personal, professional and self evaluation aspects. Methodology. Observational and cross-sectional study conducted in family health units of a city in Minas Gerais, Brazil, with 85 nursing professionals. Data were collected through a questionnaire. We used the Student t-test for differences between means and Pearson correlation analysis. Results. The mean score of the professionals on the knowledge test was 6.6 and was higher in the group that attended courses on breastfeeding. Conclusion. There is a need for continuing education, providing reflective and critical mobilization, the questioning of reality and identification of users needs.

Key words: breast feeding; education, nursing; health knowledge, attitudes, practice; family health.

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Identificar el conocimiento de los profesionales de enfermería de la Estrategia de Salud de la Familia sobre la lactancia materna y las posibles asociaciones entre el conocimiento y los aspectos personales, profesionales y de autoevaluación. Metodología. Estudio observacional de tipo transversal, desarrollado en unidades de salud de la familia de un municipio de Minas Gerais, Brasil, con 85 profesionales de enfermería. Los datos fueron recolectados mediante un cuestionario. Resultados. La media de aciertos de los profesionales en este test de conocimiento fue de 6.6 y fue mayor en el grupo que participó en cursos sobre lactancia materna. Conclusión. Se precisa una educación permanente, proporcionando movilización reflexiva y crítica, una problematización de la realidad y la identificación de las necesidades de los usuarios.

Palabras clave: lactancia materna; educación en enfermería; conocimientos, actitudes y práctica en salud; salud de la familia.

RESUMO

Objetivo. Identificar o conhecimento de profissionais de enfermagem da Estratégia de Saúde da Família sobre aleitamento materno e possíveis associações entre o conhecimento e aspectos pessoais, profissionais e de auto avaliação. Metodologia. Estudo observacional e transversal, desenvolvido em unidades de saúde da família de um município de Minas Gerais, Brasil, com 85 profissionais de enfermagem. Os dados foram coletados por meio de um questionário. Utilizou-se o teste t-Student para a diferença entre médias e a análise de correlação de Pearson. Resultados. A média de acertos dos profissionais no teste de conhecimento foi de 6.6 e foi maior no grupo que participou de cursos sobre aleitamento materno. Conclusão. Há a necessidade de educação permanente, proporcionando mobilização reflexiva e crítica, a problematização da realidade e a identificação das necessidades dos usuários.

Palavras chaves: aleitamento materno; educação em enfermagem; conhecimentos, atitudes e prática em saúde; saúde da família.

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of breastfeeding for nursing mothers and infants have been well documented by the scientific community. However, in Brazil these indicators have revealed a trend towards stabilization and are also below the recommended by the World Health Organization and Ministry of Health, of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months of life and complemented for two years or more.1 In 2008 the median duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 54.1 days and of breastfeeding it was 11.2 months.2 In Brazil, the Ministry of Health established that the encouragement of breastfeeding should be one of the basic health actions. In this context, the Family Health Program was proposed as the main pillar of care organization, incorporating sociocultural aspects present in families and the meaning of practices and actions in health.1,3 Considering the protective role of breastfeeding on infant morbidity and mortality, initiatives to promote the practice should be a priority within public health policies aimed at child health.4

Nurse practitioners without the knowledge and skills needed for the clinical management and counseling of breastfeeding contribute to the reduction of this practice.5 Professional training is essential for the success of actions of promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding, providing the health teams with competence and facilitating engagement with the users of services.6 National7-9 and international studies10-11 analyzed the knowledge of health professionals of different levels of care on breastfeeding. These studies have focused primarily on the relationship between knowledge about breastfeeding and variables such as gender, age, professional category, time working in the service, having been breastfed and personal breastfeeding experience.7,10

However, there is a gap in scientific knowledge regarding the identification of factors related solely to the knowledge about breastfeeding of nursing professionals in primary care. We hope that when identifying this knowledge and the factors that influence it, it will be possible to recognize the scenario of support to breastfeeding; to reflect on the work of professionals; to plan, develop, implement and evaluate public policies to promote breastfeeding;12 and to propose actions and policies of continuing education that meet the needs of nursing professionals in primary care and appreciate their practice in the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding. Thus, the objective of this study was to identify the knowledge of nursing professionals of the Family Health Program on breastfeeding and the possible associations between the knowledge and personal, professional and self evaluation aspects of these professionals.

METHODOLOGY

This was an observational and cross-sectional study carried out with the urban teams of the Family Health Program in Uberaba, important city of the health macro-region of the Triângulo Sul, in the State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The council consists of 50 family health teams - 46 in the urban area - which offer assistance for approximately 60% of the population. Nurses and nurse technicians participated of the study, and the established exclusion criterion was to be performing work duties in the countryside teams. Seven professionals did not participate in the survey - one nurse and six nurse technicians - for having taken part in a pilot study, for being in the hiring process or being on sick leave. The final population was composed of 85 participants; 45 nurses and 40 nursing technicians.

The data collection period was between March and July 2010. The instrument used was a self-administered and semi-structured questionnaire that had been previously tested and validated.13 It was filled out individually in the workplace at the same time by nurses and nursing technicians, with the presence of one of the researchers on site. Such care has been taken aiming to prevent discussions on the topic that could interfere with the answers. The instrument contained questions to identify the following characteristics of nursing professionals: personal (age, gender, number of children, breastfeeding of children); professional (participation in courses about breastfeeding, time working in the Family Health Program) and self evaluation (perception of one's own competence to work in breastfeeding). For the identification of knowledge about breastfeeding, the questionnaire had a test with ten questions of true (T) or false (F) type which investigated: self-care with breasts, breastfeeding technique, use of nipple shields, breast complications, breast milk composition, control of lactation and complementary feeding.

For every correct answer on the test it was given a point, with a maximum score of ten. In case of wrong answers no points were given (zero score). The final score of the knowledge test was the sum of all the correct answers given. The reference and theoretical basis used for correction of the true or false type questions was the Primary Care Guide number 23 titled 'Saúde da criança: nutrição infantil: aleitamento materno e alimentação complementar published by the Ministry of Health in 2009. It is a current and comprehensive reference in relation to the promotion of breastfeeding in Brazil. It is also inserted in a work of the Ministry of Health to raise awareness and support primary care professionals, as well as bring current strategies of addressing breastfeeding in the context of networks of care, from the primary care. Its goal is to enhance the actions of breastfeeding promotion within a full view of health care.1

The response variable considered in the study was the mean score on the knowledge test about breastfeeding. The explanatory variables were: time working in the Family Health Program (in months), breastfeeding of children (yes/no), participation in courses on breastfeeding (yes/no), perception of one's own competence to work in breastfeeding (yes or no). Data were stored in a spreadsheet of Excel (software) and validated through double entry. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 16.0 was used for statistical analysis. The variables of characterization of professionals were presented in the form of absolute and relative frequencies distribution and for the quantitative variables were calculated the following: mean and median (measures of central tendency), standard deviation and maximum and minimum values (measures of variation). A bivariate analysis was done to identify the relationship between the response variable and the explanatory variables. The mean scores were compared applying the t-Student test. The Linear Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) was used for the analysis of the correlation between the mean scores and the professional's time of work in the teams. An ? level of significance equal to 0.05 was adopted for the tests.

The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing of the University of São Paulo (Process n° 1035/2009), according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council. The development of research followed national and international ethical standards for research involving human beings, with the use of a Consent Form.

RESULTS

The age of the 85 participating professionals ranged between 22 and 55 years, with mean age of 34.2 years (SD 8.7). Most were female (82 – 96.5%) and 43 (50.6%) had no children. All the 42 (49.4%) professionals who had children were females and among them 38 (90.5%) had the experience of breastfeeding. We found that 75 (88.2%) nursing professionals participated of the breastfeeding courses at least once.

Regarding the perception of nurses about their own competence to evaluate breastfeeding technique and guide nursing mothers, 76 (89.4%) participants considered themselves prepared to play such a role. The time working in the team of the Family Health Program where professionals were allocated at the time of data collection varied from one month to 11 years, with an average of two years and six months (SD 3.3) and a median of five months. The difference between mean and median is due to the fact that the first was deflected by extreme values of nursing professionals' time of work, considering that most of them (45 - 52.9%) was working in the teams for less than six months.

The responses of the nursing professionals of the study to each of the ten questions of true or false type that characterized their knowledge about breastfeeding are presented in Table 1. Among the ten true or false type questions, four (40%) showed a higher percentage of incorrect answers. The subjects covered in these four questions refer to the hygiene of nipples with soap and water before and after each feeding, the clinical management of breast engorgement, the need for food supplementation if there is no milk letdown up to three days postpartum and the need of breastfeeding at regular intervals of time.

Participants had an overall mean score of 6.6 (SD 1.8) on the true or false test.

Table 1. Distribution of nursing professionals of the family health teams according to the responses to each of the ten questions. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2010*

* The correct answer to each of the ten questions are highlighted in gray

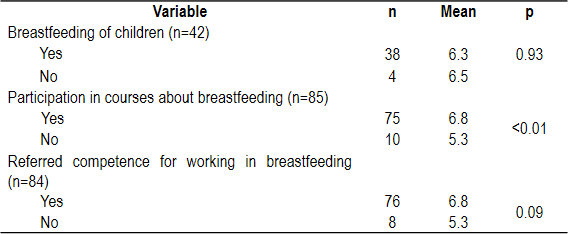

Table 2 shows the comparisons among the mean scores in the test of knowledge of the different categories defined by dichotomous variables: breastfeeding of children, participation in courses about breastfeeding and the perception of one's own competence to work in breastfeeding. The study provides evidence that there are differences between the mean scores in the knowledge test of nursing professionals who participated in courses about breastfeeding and those who did not. In other words, there is evidence that participation in courses on breastfeeding increases the knowledge of nursing professionals on the subject (p<0.01).

Table 2. Mean scores of professionals in the knowledge test, according to the explanatory variables. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2010

We observed a weak and non-significant negative correlation (r=-0.02) between the mean scores in the knowledge test and the time of work of nursing professionals in family health teams (p=0.855).

DISCUSSION

The mean score of nursing professionals in this study was 6.6, lower than that found in a multicenter study13 that used the same instrument that the present study and in which the mean score was of approximately 7.5, a performance considered reasonable by the author. Among the four questions of the knowledge test that showed the highest percentage of incorrect answers than correct answers, three are considered essential to the promotion of breastfeeding.13 These three questions address the clinical management of breast engorgement, the need for food supplementation if there is no milk letdown up to three days postpartum and the need for breastfeeding in regular periods of time. Regarding breastfeeding their children, the majority (90.5 %) of nursing professionals who were mothers had the experience of breastfeeding. This result corroborates those found in studies carried out in Montes Claros (Mato Grosso)8 and Coimbra (Mato Grosso),14 where over 80 % of professionals reported having had personal experiences with breastfeeding, either as a mother or as a companion of women who breastfed. The experience of breastfeeding may encourage the establishment of empathy between the nursing professional and the user to the extent that experiences can be shared.

The study showed no differences between the means of correct answers in the knowledge test of professionals who breastfed their children and those who did not breastfeed. This result coincides with the findings of a study conducted in the UK15 which did not find a significant difference between the knowledge about breastfeeding of women who breastfed and those that did not have this experience. On the other hand, a qualitative study revealed that much of the knowledge passed on to women by nursing professionals came from their experience in breastfeeding or observation of others, indicating a limitation in training and education of these professionals.14 A study carried out in Australia revealed that a large number of professionals who had experienced breastfeeding also had a high rate of correct answers in tests that assessed their knowledge about breastfeeding, which contradicts the findings of the present study.16

With regard to courses on breastfeeding, the majority (88.2%) of nurses and nurse technicians stated to have participated at least once, which differs from the results found in a study carried out in the city of Coimbra (MG) with professionals from a unit of family health, where 82.4% had never participated of specific courses on breastfeeding.14 The importance of this finding is evidenced in our study because the professionals who attended courses on breastfeeding had a higher average number of correct answers in the knowledge test compared to those who did not participate of these courses.

A literature review showed that continuing education on breastfeeding for nursing professionals increases their knowledge, which is a necessary precursor for the improvement of professional skills and practices.17 A study carried out in Montes Claros8 demonstrated an increase in breastfeeding rates after educational activities aimed at primary care professionals. In a research carried out in the UK the mean scores of nursing professionals in knowledge about breastfeeding revealed that there was a significant increase in knowledge after the training of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, which was maintained for six months after training.15 A randomized clinical study in Denmark showed that 52 health professionals who received training through a course of breastfeeding counseling of the World Health Organization had an increase in their knowledge about breastfeeding and in their competence to help women to overcome the most common problems of this process.18

Given the fact that most study participants attended courses on breastfeeding at least once and that the issues of the knowledge test which showed a higher percentage of incorrect responses are considered essential for monitoring breastfeeding mothers, we assume there is a limitation in the courses attended by professionals. In this context, although the present study did not have an approach to understand the nature and methodological approach of the courses taken by the study subjects, several strategies aimed at continuing education on breastfeeding were and have been implemented in Brazil for health professionals. Currently, permanent education in health becomes relevant when proposing the structure of the training of health professionals from the questioning of the work process. It comes from the meaningful learning, which happens when the learning material relates to the prior knowledge of professionals. Thus it proposes the transformation of professional practices from the critical reflection on reality and the reorganization of work, based on the health needs of healthcare users, sector management and social control in health. In this critical and reflective conception, professionals will develop in an active, reflective, critical and supportive way by questioning the reality and explicating their contradictions.19

The critical-reflexive education and continuing education in health form the basis of a problem-based teaching practice that leads to a new way of teaching issues pertaining to the health sector, such as breastfeeding. Thus, in order to offer comprehensive and problem-solving care it is necessary that the nursing professionals of the family health teams participate of continuing processes of education which make them critically reflect on their actions in the practice scenarios. This will contribute to the organization of assistance provided in health services and to the quality of the final product.19,20 However, specific teaching strategies, despite distancing professionals from an extended knowledge that considers the mother-baby binomial within a social, cultural and family context, are not invalid. Continuing education may include in the process a number of specific actions to update knowledge, as long as they are articulated to the general strategy of institutional change.19 Following this logic, in 2008 the Ministry of Health, through the adoption of lines of care aimed at promoting breastfeeding in primary care, proposed the Brazil Breastfeeding Network (Rede Amamenta Brasil), which is guided in continuing education for health professionals and aims to integrate with the other networks and initiatives to support and encourage breastfeeding.

Regarding the perception of professionals about their own skills to evaluate breastfeeding and guide nursing mothers through the proper breastfeeding technique, 76 (89.4%) considered themselves prepared to play such a role. In the United States, a study that investigated nursing professionals' knowledge and practices of breastfeeding showed that 60% of them felt able to assist breastfeeding women.21 The present study showed no difference between the mean scores in the knowledge test regarding self-assessment of the competence to work in breastfeeding. This finding differs from a research carried out in Australia which found that employees who considered themselves capable of working in breastfeeding had a better evaluation of their knowledge on the subject.16

The median of nursing professionals' time of work in family health teams where they were allocated at the time of data collection was five months. This length of time, in a way, is a high turnover of professionals, considering that the Family Health Strategy was implemented in 1996 in the municipality of study. In Francisco Morato (São Paulo), a study revealed that the average time of work of professionals in family health teams was one year and six months, higher than the average found in the present investigation.7

There was a weak and nonsignificant correlation between the mean scores and the time of work of professionals in family health teams. It was hoped that, with an increased time of work in teams, there would be an increase in the levels of knowledge about breastfeeding among nursing professionals. Data of a study carried out in Australia contradict those found in the present study, revealing higher scores in knowledge about breastfeeding of health professionals with longer time of work in their fields of work.16 Another study conducted in the metropolitan region of São Paulo found higher concentration of correct answers among professionals who worked between 24 and 30 months in the Family Health Program.7

A stable and qualified team of professionals maintains the care process, ensures the quality of services offered and expands the relationship with users, proposing solutions more easily.22 For the specific case of the promotion of breastfeeding, the turnover of nursing professionals in family health teams makes it difficult to bond with the community and thereby deepen the knowledge on the social, cultural, historical and economical context of the mother-child binomial. This situation complicates the understanding of the process of breastfeeding beyond its biological determinations and monitoring women since the beginning of prenatal care until the postpartum period, fragmenting the care and the approach to breastfeeding.23 This was the first study nationally that made the primary diagnosis of knowledge about breastfeeding of nursing professionals of the Family Health Program and also analyzed the influence of personal, professional and self-assessment aspects on such knowledge. Most studies aim to compare knowledge levels before and after performing any teaching strategy focused on the whole team and not exclusively on nursing professionals.

Final considerations. From this research, we found that participating on courses about breastfeeding has an effect on the levels of knowledge of nursing professionals on the topic. This identification allows us to propose strategies of qualification and update that suit the needs of nursing professionals, pregnant women and nursing mothers in the process of breastfeeding under their care. For the establishment and maintenance of breastfeeding, it is necessary that nursing professionals offer appropriate and accessible guidance to pregnant women, nursing mothers and their families, in order to prevent difficulties and complications that are common in this period. In order to make that happen it is necessary that nurses and nursing technicians are properly qualified to act in the promotion of breastfeeding from pregnancy to two years of children's lives or more, whether in the family health unit or the community.

Thus, starting from the idea that the qualification contributes to an increase in knowledge about breastfeeding, its association with permanent health education will provide greater knowledge on the subject and allow that professionals do a reflective and critical mobilization and problematization of the service reality as well as identify the needs of the mother-child binomial, promoting their health and enabling them to become increasingly capable for their self-care.

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Saúde da criança: nutrição infantil. Aleitamento materno e alimentação complementar. Brasília; 2009. [ Links ]

2. Venancio SI, Escuder MM, Saldiva SR, Giugliani ER. Breastfeeding practice in the Brazilian capital cities and the Federal District: current status and advances. J Pediatr. 2010; 86(4):317-24. [ Links ]

3. Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011; 377:1778-97. [ Links ]

4. Caldeira AP, Fagundes GC, Aguiar GN. Educational intervention on breastfeeding promotion to the Family Health Program team. Rev Saude Publica. 2008; 42(6):1027-33. [ Links ]

5. Fujimori E, Nakamura E, Gomes MM, Jesus LA, Rezende Ma. Aspectos relacionados ao estabelecimento e à manutenção do aleitamento materno exclusivo na perspectiva de mulheres atendidas em uma unidade básica de saúde. Interface. 2010; 14(33): 315-27. [ Links ]

6. Lundberg PC, Ngoc Thu TT. Breast-feeding attitudes and practices among Vietnamese mothers in Ho Chi Minh City. Midwifery. 2012; 28(2):252-57. [ Links ]

7. Ciconi RCV, Venancio SI, Escuder MML. Knowledge assessment of Family Health Program teams on breast feeding in a Municipality of São Paulo's Metropolitan Region. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant. 2004; 4(2):193-202. [ Links ]

8. Caldeira AP, Aguiar GN, Magalhães WAC, Fagundes GC. Knowledge and practices in breastfeeding promotion by Family Health teams in Montes Claros, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007; 23(8):1965-70. [ Links ]

9. Silvestre PK, Carvalhaes MABL, Venancio SI, Tonete VLP, Parada CMGL. Breastfeeding knowledge and practice of health professionals in public health care services. Rev Lat-Am Enfermagem. 2009; 17(6):953-60. [ Links ]

10. Chen CH, Chen JY. Breastfeeding knowledge among health professionals in Taiwan. Acta Paediatr Tw. 2004; 45(4):208-12. [ Links ]

11. Szucs KA, Miracle DJ, Rosenman MB. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes and practices among providers in a medical home. Breasfeed Med. 2009; 4(1):31-42. [ Links ]

12. Bueno LGS, Teruya KM. Aconselhamento em amamentação e sua prática. J Pediatr. 2004; 80(Suppl 5):S126-S130. [ Links ]

13. Becker D. No seio da família: amamentação e promoção da saúde no Programa de Saúde da Família [Dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2001. [ Links ]

14. Marques ES, Cotta RMM, Franceschini SCC, Botelho MIV, Araújo RMA. Practices and perceptions about breastfeeding: consensus and dissensus in the daily care in a Family Health Unit. Physis. 2009; 19(2):439-55. [ Links ]

15. Ingram J, Johnson D, Condon L. The effects of Baby Friendly Initiative training on breastfeeding rates and the breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge and self-efficacy of community health-care staff. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2011; 12:266-75. [ Links ]

16. Cantrill RM, Creedy DK, Cooke M. How midwives learn about breastfeeding. Aust J Midwifery. 2003;16(2):11-6. [ Links ]

17. Ward KN, Byrne JP. A Critical Review of the Impact of Continuing Breastfeeding Education Provided to Nurses and Midwives. J Hum Lact. 2011; 27(4):381-93. [ Links ]

18. Kronborg H, Varth M, Olsen J. Health visitors and breastfeeding support: influence of knowledge and self-efficacy. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:283–88. [ Links ]

19. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Gestão do Trabalho e da Educação na Saúde. Departamento de Gestão da Educação. Curso de formação de facilitadores de educação permanente em saúde: unidade de aprendizagem – práticas educativas no cotidiano do trabalho em saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; Brasília; 2005. [ Links ]

20. Balbino AC, Maia TM, Rosa TCA, Silva FF, Cecon PR, Cotta RMM. Educação permanente com os auxiliares de enfermagem da estratégia saúde da família em Sobral, Ceará. Trab Educ Saúde. 2010; 8(2):249-66. [ Links ]

21. Hellings P, Howe C. Breastfeeding knowledge and practice of pediatric nurse practicioners. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18(1):8-14. [ Links ]

22. Anselmi ML, Duarte GG, Angerami ELS. Employment survival of nursing workers in a public hospital. Rev. Latino-am. Enfermagem. 2001; 9(4):13-8. [ Links ]

23. Monteiro JCD, Nakano AMS, Gomes FA. O aleitamento materno enquanto uma prática construída: reflexões acerca da evolução histórica da amamentação e desmame precoce no Brasil. Invest Educ Enferm. 2011; 29(2): 315-21. [ Links ]

text in

text in