Introduction

Globally, between 2001 and 2010 there was a rate of cancer incidence of 140 cases per million children under 15 years of age, which corresponded to the diagnosis of nearly 300,000 new cases during that period,(1) with leukemia being the most common type of childhood cancer (rate of 46.4 per million), followed by tumors of the central nervous system (rate of 28.2 per million) and lymphomas (rate of 15.2 per million).(2) During the period from 2007 to 2011, it was estimated that for Colombia the annual incidence rate for all types of tumors, except skin, in the country was 11.4 per 100,000 in boys and 8.7 per 100,000 in girls.(3)

Childhood cancer affects families in several items of their lives, including the financial, a situation that can influence upon the late initiation of treatment, adherence, and remission to specialized levels of care, which may mean the difference between life and death.4) Likewise, cancer treatment in its early stages is intense because complete remission is expected, needing frequent hospitalizations and the transfer of the child and the caregiver from the home to the hospital, which causes disorders in the family life routine,(2) in the role of each family member, in the schooling of the sick child and of other children.(5)

Within the financial affectation of childhood cancer in families, literature reports a change in the routines that affects the lives of the families, influencing not upon the unity, relationship, and emotional state of its components; it will also suffer at the work level due to the loss or abandonment of work, which has financial repercussions.6) Upon the need for continuous companionship for the child during treatment and course of the illness, some parents must abandon or diminish their hours of work, a condition that brings as consequence a decrease in the family income.7

The burden of care is identified both in the principal caregiver as in the family group by the alteration in the family functionality and impact upon the financial, social, and personal spheres.8) The family economic burden is defined as the added financial effort the family of a child with cancer must assume to provide the care needs.9 The family financial affectation has been studied in families of people with chronic illness in Colombia10,11 and Guatemala,12 reporting that the greatest affectation takes place in the health area. In childhood cancer, the particularity of the experience and treatment suggests differentiating this phenomenon from general chronic illness, which is why the aim of this study was to determine the family economic burden associated with caring for the child with cancer.

Methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted between 2015 and 2017. A convenience sampling was done of 50 families of children with cancer linked to a foundation in Cundinamarca (Colombia); this institution has a social responsibility program in which it offers comprehensive companionship to children from vulnerable population who are stricken with lupus or cancer during hospitalization or remission, so they can satisfactorily complete their health treatments in Bogotá. The foundation offers aid in the modalities of regular child and floating child; the first is the child who attends the institution regularly and receives weekly groceries and when in treatment receive a monthly hospitalization kit; the floater is the child forwarded from their city of origin for treatment in Bogotá, during that period the foundation offers them the same support offered to a regular child and, additionally, the floater children participate in the foundation’s ludic, recreational, and spiritual events.

The study informant was the principal family caregiver of the child with confirmed diagnosis of childhood cancer and who was in the phase of treatment consolidation or maintenance. Inclusion criteria included being over 18 years of age and caring for the child for at least two months; the latter for the purpose of quantifying consumption before and after the cancer diagnosis.

To gather data, a questionnaire was used containing sociodemographic information of the child and the caregiver. To measure the additional family financial effort associated to caring for a child with cancer the study used the family survey “Financial cost of caring for chronic illness” by Montoya et al.,(11) which inquires on the actual effective consumption attributable to caring for individuals with chronic illness, the perception of burden associated to the financial cost, and - lastly - the observations related to the cost of caring. This survey has adequate facial and content validity criteria under criteria of clarity, sufficiency, coherence, and relevance. The survey quantifies family financial expenditure in Colombian pesos (COP) and has open response spaces that permit expanding on the causes of the increased expense.(11)

Understanding as economic burden the additional financial effort the family of a child with cancer must assume to meet the care needs,9 and the level of burden as the relative weight of the financial cost in each of the items of the actual effective consumption attributable to caring for the child with cancer, which was obtained by calculating a quotient based on the amount of money that the family consumes in caring for the patient and the amount of money the family consumed before the illness, resulting in an independent proportion of the monetary value. The resulting quotient is converted into degrees of an angle through the tangent arc function, with higher number of degrees meaning a higher level of burden.13

The analysis of the economic burden was conducted through the methodology known as CARACOL (Economic burden attributable to caring for a person with chronic illness in Colombia), which has two facets: quantification of the level of burden and financial cost of the burden.(10) The first seeks to identify the level of the impact or relative weight of the financial cost in each of the items or grouping of these and the second is aimed at describing the peculiar attributes of consumption of the family group associated to caring for the patient with chronic illness. To specify the relative weight of the burden, the study determined the amount of money the family invested in caring for the child with cancer and this was contrasted with the amount of money the family spent prior to the onset of the illness in a given item of the household economy. The quotient of both amounts expressed the proportion of the consumption attributable to the illness with respect to the prior family consumption in the specific item, independent of the monetary value, which is represented in a snail emulous formed from the conversion of the quotient into sexagesimal angles that permit the representation of level of burden. To describe the peculiar attributes of consumption by the family group, the nominal and ordinal variables were analyzed through descriptive statistics determining the frequency and percentage. To analyze interval variables, descriptive statistics were used by means of distribution measures and central tendency. The study was carried out based on the ethical guidelines for research with humans, considering that its risk was minimum. Caregivers provided informed consent and the Ethics Committee from the Faculty of Nursing at Universidad Nacional de Colombia endorsed the study with authorization from the Foundation’s directors.

Results

General characteristics of children with cancer and of their caregivers

Seventy percent of the children suffer from leukemia, with no gender tendency given that 50% were girls and 50% were boys of which 54% were out of school. It is relevant to note that in relation to the department from which the families of children with cancer came from 38% were from Bogotá, followed by 20% from Cundinamarca, but 56% lived in Bogotá and 26% in Cundinamarca, evidencing that some families have moved from their department of origin toward the capital or to more nearby places (Table 1).

Table 1 General characteristics of the 50 children with cancer and sociodemographic characteristics of the family

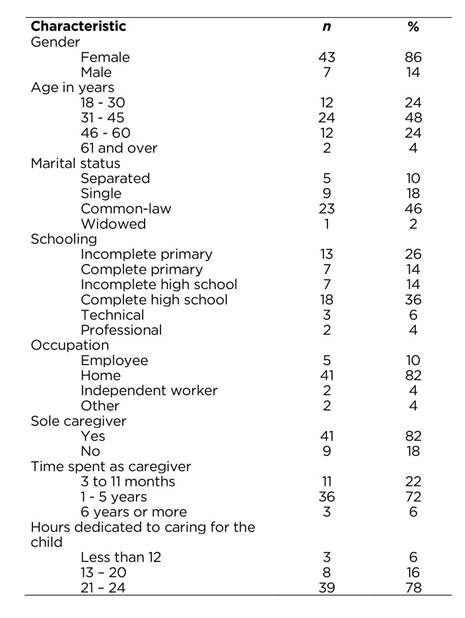

Eighty-six percent of the family caregivers are women and 14% men, whose age range prevails between 31 and 45 years, 46% live in common-law union, and 82% are sole caregivers; with respect to the number of hours they dedicate daily to caring for the child with cancer, it is highlighted that 78% dedicate from 21 to 24 hours and only 6% less than 12 hours (Table 2).

General expense and associated to caring for the child with cancer

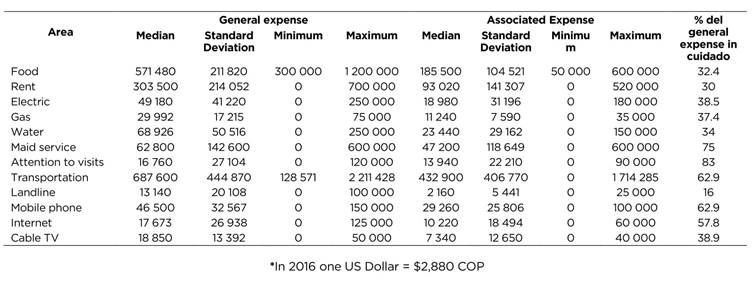

With respect to food costs, an expense is evidenced associated to caring for the child with cancer by 32.4% due to the nutritional changes that must be accepted. In relation to the expense in rent, 74% spend a monthly average of $303,500 COP; from this expenditure, 30% corresponds to expenses associated to caring for the child due to having to move to another region and in other cases to the change of housing because of infrastructure. Public utilities, like electricity, gas, and water also show increased expenditure associated to care, which is at 38.5%, 37.4%, and 34%, respectively, this is due to the frequent preparation of foods and increased measures of personal and household hygiene.

In terms of health costs, 90% of the family caregivers do not assume said costs due to the child’s illness, given that they are affiliated to a contributive or subsidized healthcare provider institution. None of the caregivers complements this service with pre-paid medicine. Family caregivers face increased expenses in elements for personal and household hygiene; on average, the monthly general expense is $152 120 COP of which an average of $60 100 COP is for caring for the child. This expense is increased by the consumption of special elements, like masks, soaps, frequent use of disinfectants and home cleaning elements.

With respect to the transportation expenses, monthly, the expense associated to care is 62.9%; the cause for this consumption is that the families see the need to travel by taxi, and others must do so on inter-municipal vehicles because they live in remote regions. Regarding communications, the families have an increase because the child is forced to miss school during treatments, with internet and television becoming sources of recreation and education for the children. The families have an average general monthly expense of $96 163 COP of which 50.9% is attributed to caring for the child, as illustrated in Table 3.

Degree of family economic burden associated with caring for the child with cancer

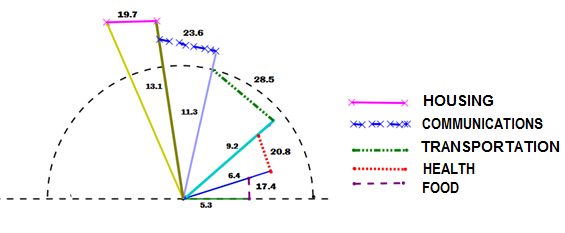

The children’s families saw an increase in the actual effective consumption in each of the items, which is associated to the illness. The biggest burden is in transportation with an angle of 28.5°, explained because one in four families uses taxis as means of transportation and those living in remote regions seek inter-municipal vehicles for transportation. The second place is in the expense for communication with an angle of 26.3°, this consumption increased in the families because most of them acquired mobile telephones, internet, and cable television as means of recreation and education for the children when they could not go to school or to public settings due to the illness.

The health item reported an angle of burden of 20.8°; this burden is mainly attributed to the expense in elements for personal and household hygiene, as well as to the expense in medications included in the Obligatory Health Plan and to additional costs not contemplated in said plan. In housing, the burden is of 19.7°, given that some families changed housing due to problems with the infrastructure and others moved from their department of origin to gain better access to hospital centers. With respect to the actual effective food consumption, the angle of burden is 17.4°; families expressed that this increase is due to the child’s change in diet (Figure 1).

Consequences of the family economic burden associated with caring for the child with cancer

The financial wear associated to caring for the child with cancer has been cause for concern for all the caregivers (high 58%, medium 38%, and low 4%), creating conflicts in 92% of the families. The costs of caring for the child who is ill are assumed by various family members (36%); frequently, the incomes are not sufficient and families are obligated to go into debt or sell their goods.

Discussion

This study evidenced that families had to move from their place of residence to Bogotá to have access to the child’s treatment. This finding is congruent with that reported in the literature, given that most pediatric cancer centers are in the principal cities, obligating a significant number of patients to travel long distances for the cancer treatment.(14 At the same time, this expense is one of the causes for abandoning treatments, given that accessibility to health services is hindered and some families decide to end this struggle prior to culminating the treatments,2,8 which results in social financial difficulties.(14) Frequently, caregivers abandon their occupations to dedicate themselves to caring for the child. This possibly worsens the families’ financial situation, inasmuch as it is clear that the success of the medical care of children with special needs not only depends on the professional services, but also on the time invested by the family, which affects their work status.15) The aforementioned demonstrates that caring for the patient is a task of almost exclusive dedication by the caregiver,16 especially by women, given that the study found that 86% of the caregivers are females, a situation evidencing the woman’s role in providing care, in particular in situations of chronicity.(17)

With respect to the number of hours per day dedicated to caring, 78% of the family caregivers dedicate between 21 and 24 hours, which agrees with studies that justify this high dedication in multiple tasks performed by the caregivers, among which there are feeding, accompanying, bathing, dressing, carrying, transporting, administering medications, taking to the doctor, acquiring medicine, and scheduling medical appointments for the chronic patient.7) Said dedication increases in children with cancer, who due to their condition and age must always be accompanied, needing a family caregiver continuously; more so during moments of hospitalization, which can last for days, weeks, and even months. This is when family caregivers are obligated to change their family and social routines to accept this new role.(18,19)

Families of children with cancer see increases in the different items of the family budget, consequential of the diverse experiences they endure. One of these is that the children are forced to miss school, which leads to the need to improve information technologies to provide the child some distraction while in the hospital and at home. Sánchez- Herrera et al. (10) indicate that families of chronic patients have seen increased payments in mobile phone services, internet, and television to meet the patient’s needs for recreation and communication.

With respect to the sources of income, our study showed that families receive help from their relatives and from the Foundation, but - in spite this - they consider that expenses are higher. Added to this is the fact that many family caregivers have to leave their jobs; consequently, diminishing their income and obligating them in some cases to request loans, which agrees with that reported in the Colombian Andean region, where the families assumed debts to provide for the needs of those with chronic illness.10

Among the sources of support, the families share expenses with close relatives, which is beneficial because the parents are the principal source of caring. It is necessary for them to have a broad social network that provides them help to confront the shock of the diagnosis, the subsequent treatment, and its results.20 In general, for families of children with cancer, economic and physical support from other relatives is very important, given that this facilitates complying with medical and chemotherapy appointments; this support usually comes from the solidarity of extended families. In addition, part of the financial wear due to caring for the child generates a high level of concern, given that conflicts arise within the family group related to how finances are managed, with the lack of sufficient money being one of the principal causes. In these cases, social life, recreation, and food habits are modified by the treatment for the child with cancer.21

Additionally, economic burden was noted related to food, where the families are not concerned with satisfying the food needs of all its members, given that their priority is the care process and caring for the child with cancer, leading to decisions, like providing the best food to the child. This agrees with the literature where it was found that the child’s dependency on the family hinders the caregivers’ feeding or, rather, it takes place under inappropriate conditions, whether in the hospital or the street, which could impact upon their health status.22

It was evident that the biggest burden for the families was transportation, with a weekly average of $160 440 COP of which 62.9% of the total expense is associated to care. Children with cancer could not be exposed to environments that caused them major discomfort, which is why their families had to change their usual means of mass transport for one that represented less risk to the children. Some families lived in rural zones and traveling to the hospital centers demanded an additional expense. Fluchel et al.,14) found that the majority of pediatric cancer centers are in the principal cities and a significant number of patients travel long distances for cancer treatment. This expense forces many to abandon treatment; the long distances make it difficult to gain access to the health services and some families decide to end this struggle before culminating the treatments. Housing expenses were significant; some families moved from their place of residence to improve accessibility to health services; these findings are similar to those reported in the literature, which has found a surprisingly high percentage of families had moved from their homes due to their child’s cancer. Given their considerable efforts, financial costs associated to the transfers and the fact that their children’s lives are at risk because they live so far away, the families decide to move from their city of origin. Colombia’s legislation 1388 of 2010 "for the right to life of children with cancer in Colombia", seeks to guarantee access to early diagnosis, treatment, follow up, and support, including financial; but in spite of this, for many families enduring the experience of childhood cancer continues being a struggle lacking sufficient financial support, which implies the prevalence of negative impacts on not adhering to treatments and the survival of children with cancer.

The conclusion in this study is that families of children with cancer bear a high economic burden, stated in order of importance with expenses in transportation, communications, health, housing, and food. This economic burden can interfere with adherence to treatment and, hence, with the child’s survival. This research shows the need for the health staff to better understand the experiences of families of children with cancer in relation to the economic burden they must endure and recognize the families as principal caregivers who require support and more so during moments of hospitalization, to develop strategies that integrate care actions with actions at home to minimize readmissions of the children and improve the quality of life of the children and their families. The study also reveals the need to include in public health policies support for the families of children with cancer to avoid impoverishment, improve the quality of life of the families and the children, and avoid - in the long term - illnesses of family caregivers and family members related to the burden of care.

text in

text in