BACKGROUND

COVID-19 is a disease originating from the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2. The first case was reported to WHO on December 31, 2019, upon being informed of a cluster of "viral pneumonia" cases reported in Wuhan, People's Republic of China 1. Three phases of SARS-Cov-2 have been described: early infection, pulmonary phase, and hyperinflammation. The first phase of Covid-19 originates with inoculation and early onset of illness. At this stage, infected persons begin to incubate the disease, and to present the first mild symptoms, generally manifested as general malaise, fever, and cough. As the experts explain, during this time, the virus multiplies and takes up residence in the host, affecting the respiratory system to a greater extent. Therapy at this stage should be directed at symptomatic relief.

In the second stage of the coronavirus, viral multiplication and localized inflammation in the lung occur. Patients who reach this stage present a viral pneumonia, with cough, fever, and, probably, hypoxia. At this stage, it is suggested that most Covid patients be hospitalized, undergoing treatment and constant monitoring of their vital signs. Treatment will vary depending on whether or not they have developed hypoxia.

In the last phase of the coronavirus, the disease becomes severe and produces systemic hyperinflammation. Very few patients reach this stage, in which "shock, vasoplegia, respiratory failure, and even cardiopulmonary collapse can be detected", as experts report. In addition, if any systemic organ is affected, it would become apparent in this period (Siddiqi & Mehra, 2020).

Clinics and hospitals focused their efforts during the pandemic on finding treatments, medical intervention protocols, medication to treat mild symptoms, prevent complications, and care for severe and critical cases. Psychiatric physicians at one U.S. hospital regularly met with critical care providers to offer group and individual support to physicians in need. Physicians also found new approaches not to succumb during the most overwhelming periods. At the height of the pandemic, physicians took turns emailing a "Daily Note of Positivity" that highlighted success stories of recent extubations of COVID-19 patients, and inspiring stories of patients who recovered and were discharge 3,4 .

Few studies have been found on psychological or psychiatric care for patients with severe or critical COVID-19. Most research points to psychological and psychiatric care and intervention for health care providers in critical care units. There are also studies on the psychological and psychiatric care of patients in the recovery and post-COVID-19 period.(5-7. As there are several investigations of post-COVID-19 complications.(8-10. Survivors of acute critical illness frequently suffer from post-acute critical illness syndrome (PICS), which consists of a set of physical, cognitive, and psychological deficits that arise from critical illness, and that remain long after the patient is discharged from the ICU 11.

ICU admission for COVID-19 results in family isolation, uncertainty, and restricted human interaction, factors that predict long-term psychological harm to ICU patients and their families 12.

This article reports a successful case of psychological care and intervention for a patient with COVID-19, and his family, during his stay in the critical care unit of a Colombian hospital. This case demonstrates the importance of interdisciplinary work between medical and psychological care providers. Synchronized and coordinated work between physicians and mental and emotional health care providers could become a new trend in the care and intervention of patients in critical care.

CASE PRESENTATION

The following is a case report that demonstrates the importance of therapeutic support for both, the patient and family, during an ICU stay. The patient and his family received psychological care and intervention, firstly, to minimize the fear generated by entering the emergency department in order to receive medical care; secondly, to accompany him and to inform and explain to him all the medical processes and procedures he would receive in the hospital; constant accompaniment was also provided to his family with the aim of keeping them informed and calmed, to be a source of support for the patient, and, also, to become a source of support for the health care providers ( physicians and nurses).

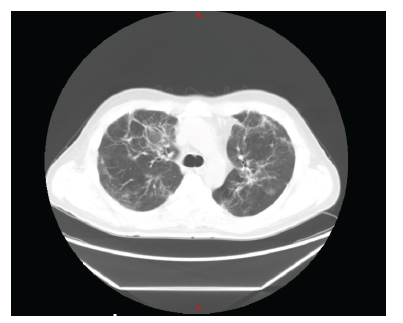

The patient is a 44-year-old male, residing in Colombia, who was admitted to the emergency room on November 24, 2020. His illness started on November 15, 2020, due to fever of 38-39 degrees Celsius, dry cough, anosmia. He presented positive PCR test for SARS CoV2 on November 17. During the first 4 days, he manifested intermittent episodes of dyspnea and chest pain, so he decided to go to the emergency room, where the diagnosis of atypical viral pneumonia was confirmed. Initially, oxygen saturation and inflammatory markers were normal, and it was suggested to continue treatment at home. On November 24, he was readmitted due to worsening symptoms presenting desaturation and dyspnea on exertion. His chest CT scan on admission showed a mixed pattern with ground-glass infiltrates and bilateral diffuse alveolar consolidation (figure 1).

The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, a medical condition treated with Valsartan 160x1 and Amiodipine 10x1.

RESEARCH

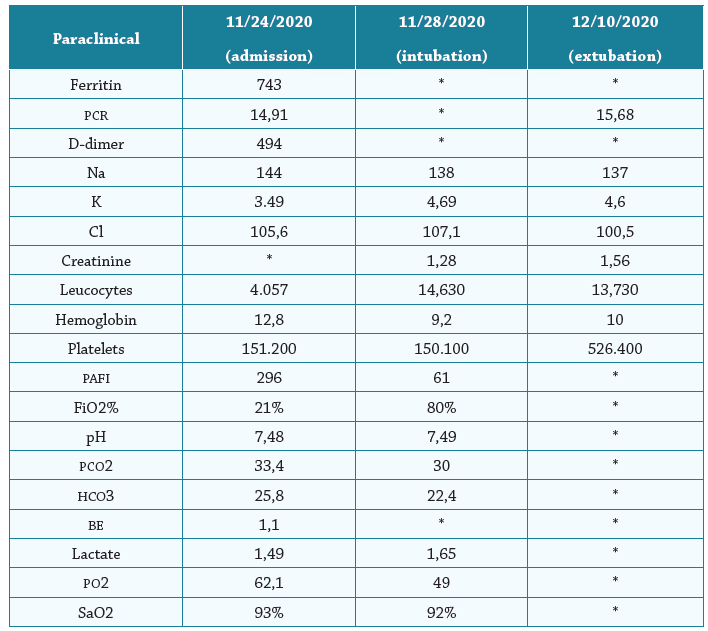

Physical examination on admission (11/24/2020) showed a patient in acceptable general condition: alert, oriented, cooperative on physical examination. Blood pressure (BP) 125/ 66 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 78 beats per minute, respiratory rate (RF) 18 breaths per minute, temperature 36.3°C, oxygen saturation 100%. The paraclinical findings on admission and during hospital stay are described in Table 1.

Table 1 Paraclinical tests at admission, intubation, and extubation

* No report

Fuente: Elaboración propia

Due to moderate hypoxemia, computed axial tomography results, and increased inflammatory markers, in-hospital management in the intensive care unit was initially advised to keep the patient under continuous monitoring of vital signs. Initial management with steroids (Dexamethasone 6mg IV, every 24 hours) and oxygen therapy with nasal cannula at 28%, but with the need to increase Fio2, due to increased dyspnea.

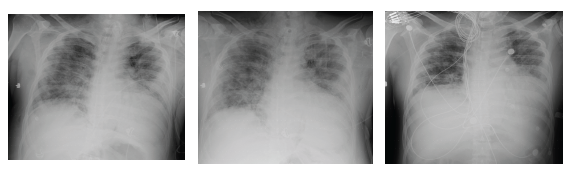

On November 28, 2020, the patient presented anxiety and increased dyspnea. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and increased bilateral infiltrates in both lung fields in the chest X-ray, evolved with progressive deterioration of general condition with severe hypoxemia in the context of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) that required orotracheal intubation, connection to mechanical ventilation with requirements of high Fio2, and management of airway pressures. Progression to multi-systemic organ failure with need for vasopressor support. During the 10 days in which the patient remained intubated, he received psychological support, and a family member (who received psychological support throughout the patient's stay in the unit) was allowed daily admission. The hospital authorized psychological and family support during the patient's stay in the COVID intensive care unit. On leaving the ICU, the patient mentioned that, under sedation, he felt the support of his therapist: in the reverie produced by the effect of the sedatives, he visualized her sitting next to him, accompanying him, and sending him rays of light, and he commented that he felt very calm at that moment. He would ask her: "How long will I be here? How are we doing?" And he received an answer from the therapist, not in words, but mentally: "calm down, it won't be long, everything will be all right". He affirms that he saw her smiling and assured of what she was saying, and he felt very calm. He also commented that he heard, on several occasions, the doctors and nurses talking to each other, and he was very anxious when he knew from what he heard that things were not going well. The patient and his family received daily psychological therapy support during his stay in the hospital.

Due to prolonged intubation, the patient underwent tracheotomy for airway management, and was discharged from the unit on December 22, being, then, transferred to the general ward. On December 23, he presented an episode of dyspnea, oppressive chest pain, hypotension, and loss of consciousness, absence of pulse was observed, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers were started, coming out of arrest after 5 minutes with sinus rhythm, requiring readmission to the ICU, where severe mitral valve prolapse was recorded (known antecedent). He slowly progressed to stability, and was thus discharged from the intensive care unit to the general ward on December 29, where he continued his recovery and pulmonary rehabilitation process until his release (medical discharge) on January 14, 2021. The patient was medically discharged with a diagnosis of valvular pathology, discussed at the medical-surgical meeting, and intervention by cardiac surgery was determined after cardiopulmonary recovery and improvement of musculos-keletal status. He underwent successful surgery months later.

Fuente: Elaboración propia

Figure 3 Evolution x-ray mechanical ventilation from 28/11/2020 to extubation on 10/12/2020.

Fuente: Elaboración propia

Figure 4 X-ray evolution from tracheotomy to hospital discharge on 01/14/2021.

DISCUSSION

The research that appears in the scientific literature on psychological or psychiatric care in patients in the Covid ICU is very scarce. The studies are focused on care and intervention in health care providers13,14, and post-Covid care and intervention.

Psychological and psychiatric accompaniment and support could be very useful for every moment experienced by family members and patients in an ICU 15, as shown in a publication by US researchers in which a clinical case was used to discuss a new proposed approach for weaning from analgesic sedation in patients recovering from long-term mechanical ventilation. Research supports decreasing the use of sedation in mechanically ventilated patients, yet many patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) receive prolonged infusions of opioids and sedatives. This article suggests a protocolized multimodal weaning strategy, implemented by a multidisciplinary care team, to reduce the potential harm of both over- and under-sedation.

It is stated that there is currently no strong evidence from randomized clinical trials to support a particular weaning strategy in adult ICU patients.(16. During the pandemic, patients who were hospitalized and in ICU reported that one of the most complex situations during their process was feeling alone, far from their families; some expressed feeling abandoned by their families. These feelings could explain many of the physical reactions that prevented them from recovering and being discharged from the hospital. Patients in the critical care unit go through various emotions, sensations that can produce physical reactions that could alter vital signs: blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation. The emotions manifested by the patient presented in this publication were: rage, anger, helplessness, sadness, depression 17, anguish, fear, panic. Each of these emotions were identified and worked on throughout the illness, in order to consciously elaborate and resolve them. The hospital allowed access to the family and video-call therapy sessions during his stay in the ICU. The patient recounted being able to perceive the company of his family and the therapist even while under sedation. These statements are shared in this document to invite the clinical scientific community and mental health service providers to develop research from which results can be generated as protocols for the care of adult and child ICU patients.

There are no empirical evidence-based guidelines that pinpoint the exact time at which sedation can be safely withdrawn in patients with severe ARDS; in general, ICU teams should attempt to withdraw sedation as soon as the patient no longer needs it to maintain clinical stability. A study of 336 mechanically ventilated patients showed that pairing a protocolized sedation weaning strategy with spontaneous breathing trials (SBT) improved ventilator-free days, compared to the control group that did not receive the SBT protocol. In clinical practice, sedation weaning begins when patients are hemodynamically stable (no requirement for high doses of vasopressors or inotropes), with a P/F ratio greater than 200, and when transition to pressure support is anticipated within the next 48 h. If excessive sedation is believed to be the cause preventing ventilator weaning, sedation weaning should be performed prior to the aformentioned parameters. The review indicates the importance of informing patients and/or families when sedation weaning will begin, and sharing the results of this process with the patient and family. This will help engage the patient/family in care, mitigate anxiety and psychological stress, and it allows them to participate in identifying withdrawal symptoms 18

A study whose main objective was to evaluate the ICU stay from the point of view of patients and family members shows that, in the case of the patients, the aspects that lead to lower satisfaction are related to their poor inclusion in the decision-making process, having little control over the provided treatment, the waiting room, poor communication with the physicians, and the ICU environment 19,20. This study concludes that the general evaluation of the ICU stay was positive, with some aspects to be improved. Knowing this reality is the first step in creating programs that design measures to reinforce the aspects that are well rated, and to improve those that are poorly rated, in order to increase the perception of satisfaction with the quality of care in critical care units 21

The pandemic created a plethora of challenges that required specific and immediate solutions to manage the care of critically ill and dying patients. It was necessary to regulate visitation to avoid social isolation and dying alone. Finding alternative forms of communication, as well as interprofessional and interdisciplinary support, is a precondition for individualized care of critically ill and dying patients and their relatives. Infection prevention measures must be communicated clearly and transparently in hospitals 22. A qualitative study in the United States concludes that restricted visitation 23 causes substantial psychological harm to family members of critically ill patients. Information gleaned from the voices of family members place special attention on considering evaluating ICU visitation restriction measures, and it suggests investment in infrastructure (including staff and videoconferencing) to assist communication. Family-derived recommendations are shared for implementing the 3C communication principles (contact, consistency, and compassion) to guide and enhance communication in times of physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond 24-26

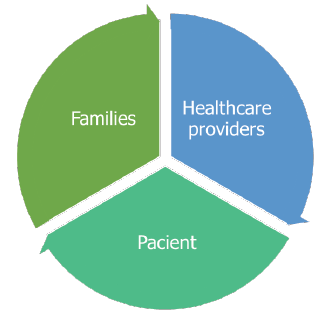

It is necessary to propose a protocol for the psychological care of health care providers, patients, and families. Using science, it will be possible to create a protocol in which equal and special attention is paid to these, the three most important aspects in a critical care unit. The aforementioned is presented in a study led by researchers from Iran. The results of this and other research conclude that it is possible to increase the awareness of health system administrators, especially hospitals, about the level of stress 27,28, anxiety, and depression; and to succeed in providing psychological support programs to improve the mental health of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic 26,29,30

Fuente: Elaboración propia

Figure 6 Comprehensive protocol for intervention and psychological care in the Critical Care Unit.

Burnout syndrome has always been common among team members in a critical care unit, and during the 2019 Coronavirus pandemic, it substantially increased, regardless of whether patients had COVID 19 or not. Nurses had a higher prevalence of burnout, and female physicians were significantly more affected by burnout than men 31-34.

Nurses played a very important role during the pandemic, providing spiritual care to their patients. They not only provided patient care, but also offered spiritual and emotional support. Although they believed that spirituality was important to help patients cope with the disease, they did not have a consensus definition of spirituality. Work overload, insufficient time, and lack of training were perceived as barriers to the provision of spiritual health 35. COVID-19, as well as different physical health conditions, have an important emotional and mental component. By joining the efforts and knowledge of different professionals: physicians, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, it will be possible to obtain very good results in the health process of ICU patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Few studies were found on the usefulness of psychological or psychiatric care for patients with severe or critical COVID-19. Most of the recently reported studies are focused on psychological care for families and health care providers.

The case reported in this article, a case with a myriad of complications, highlights the importance of psychological care for patients in the critical care unit (ICU). It is crucial, in the efforts required to achieve the patient's recovery and medical discharge, to integrate psychological care programs. Many of the sensations and emotions experienced in the ICU could produce physical reactions that hinder the patient's hemodynamic stability and recovery process.

We suggest, to the scientific community, to continue developing studies that provide findings in order to create an integrated care and intervention plan between family, patient, and medical staff, as a result of a rigorous research process.

Every day, there is more evidence of the relationship between body and mind. Also, of the importance of taking care of mental health to avoid diseases that are mainly caused by unresolved emotions and mental weaknesses. COVID proved to be not just a physical disease. Fear, uncertainty, and collective panic due to the pandemic itself were emotions that aggravated patients who already had chronic physical illnesses. Psychological care in crisis can help improve the symptoms of an acute respiratory crisis.