Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Agronomía Colombiana

Print version ISSN 0120-9965

Agron. colomb. vol.34 no.2 Bogotá May/Aug. 2016

https://doi.org/10.15446/agron.colomb.v34n2.55616

Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/agron.colomb.v34n2.55616

Hymenopterous parasitoids of Dasiops (Díptera: Lonchaeidae) infesting cultivated Passiflora spp. (Passifloraceae) in Cundinamarca and Boyaca, Colombia

Parasitoides himenópteros de Dasiops (Diptera: Lonchaeidae) que infestan Passiflora spp. (Passifloraceae) cultivadas en Cundinamarca y Boyacá, Colombia

Maikol Santamaría1,2, Everth Ebratt3, Angela Castro3, and Helena Luisa Brochero1

1 Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá (Colombia).

2 Faculty of Engineering, Corporacion Universitaria Minuto de Dios (Uniminuto). Bogotá (Colombia). msantamaria@uniminuto.edu

3 National Phytosanitary Laboratory Diagnosis, Tibaitata Research Center, Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA). Bogotá (Colombia).

Received for publication: 5 February, 2016. Accepted for publication: 30 June, 2016.

ABSTRACT

Dasiops spp. are the most important pest in cultivated Passiflora plants. Larvae of these fruit flies are herbivores, feeding on flower buds and fruit of yellow passionfruit, sweet granadilla, banana passionfruit and purple passionfruit crops located in Cundinamarca and Boyaca, Colombia. Geographic distribution, natural abundance and percentage of parasitoidism for every Dasiops species by each plant species were determined. Aganaspis pelleranoi (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) was found to be a parasitoid of D. inedulis (14.19-50.00%), infesting flower buds of yellow passionfruit and fruit of sweet granadilla (7.41%). Microcrasis sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) was found to be parasitizing both D.gracilis (0.83-3.13%) and D. inedulis (0.83%) in purple and yellow passionfruit. Trichopria sp. and Pentapria sp. (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) were found to be parasitizing D. inedulis (40.00% and 4.17-20.00%, respectively) and D. gracilis (1.69-22.22% and 1.67-29.17%, respectively) in purple passion fruit. Dasiops caustonae was found to be infesting banana passionfruit only in Boyaca, naturally parasitized by Pentapria sp. (11.11-33.33%). Because Pentapria sp. had a wide geographical distribution as an idiobiont of Dasiops spp. pupae, in all of the assessed cultivated Passiflora species, despite a high selection pressure by chemical control distributed at regular calendar intervals, it would be a crucial strategy in pest management control. Collecting fallen flower buds and fruit infested by Dasiops spp. is important to truncate the life cycle of fruit flies and allow emergence of parasitoids. This simple cultural strategy could have important implications in reducing production costs, increased crop yields and environmental care.

Key words: Hymenoptera, fruit flies, Lonchaeidae biodiversity.

RESUMEN

Dasiops spp. son la plaga más importante de plantas cultivadas de Passiflora. Las larvas de estas moscas de la fruta consumen botón floral y fruto de cultivos de maracuyá, granadilla, curuba y gulupa localizados en los departamentos de Cundinamarca y Boyacá en Colombia. Se determinó la distribución geográfica, abundancia natural y porcentaje de parasitoidismo para cada especie de Dasiops en cada especie de planta. Aganaspis pelleranoi (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) fue encontrada como parasitoide de D. inedulis (14,19-50,00%) que infestó botón floral de maracuyá y fruto de granadilla (7,41%). Microcrasis sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) fue encontrada como parasitoide de D. gracilis (0,83-3,13%) y D. inedulis (0.83%) en gulupa y maracuyá. Trichopria sp. y Pentapria sp. (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) fueron encontradas parasitando D. inedulis (40,00% y 4,17-20,00%, respectivamente) y D. gracilis (1,69-22,22% y 1,67-29,17%, respectivamente) en gulupa. D. caustonae fue encontrada infestando curuba únicamente en Boyacá y parasitada naturalmente por Pentapria sp. (11,11-33,33%). Debido a que Pentapria sp. mostró amplia distribución geográfica como idiobionte de pupas de Dasiops spp., en todas las especies de Passiflora estudiadas, a pesar de la presión de selección por el control químico implementado tipo calendario, sería una estrategia crucial en el control de plagas. La recolección de botones florales y frutos infestados por Dasiops spp., es importante para cortar el ciclo de vida de las moscas de la fruta y permitir la emergencia de parasitoides. Esta simple estrategia cultural podría tener importantes implicaciones en la reducción de costos de producción, el aumento de los rendimientos de los cultivos y el cuidado del ambiente.

Palabras clave: Hymenoptera, moscas de la fruta, Lonchaeidae, biodiversidad.

Introduction

The species of cultivated Passiflora that are the most widespread and important in the national and international markets are yellow passionfruit (Passiflora edulis f. fla-vicarpa Deg.), sweet granadilla (P. ligularis Juss.), purple passionfruit (P. edulis Sims and banana passionfruit (P. tripartita var. mollissima Nielsen & Jorgensen) (MADR, 2015).

The flies of the Dasiops Rondani (Diptera: Lonchaeidae) genus are the insect pests of major economic importance in cultivated Passiflora, due to the habit of the larvae consuming the internal structures of flowers bud and fruit (Santamaria et al., 2014; Castro et al., 2012). They are responsible for causing production losses in excess of 50% (Castro et al., 2012).

Different species of flies of the Dasiops genus that infest cultivated Passiflora are currently recognized. Dasiops inedulis Steyskal infests flower buds of purple passionfruit, sweet granadilla and yellow passionfruit. Specific infestations exist regarding the vegetal species: D. yepezi Norrbom and McAlpine in sweet granadilla, D. gracilis Norrbom and McAlpine in purple passionfruit and D. caustonae Nor-rbom and McAlpine in banana passionfruit (Santamaría et al, 2014; Castro et al., 2012).

To control Dasiops spp., most farmers implement conventional strategies based on the application of synthetic chemical insecticides on a calendar basis (Wyckhuys et al., 2012). However, this management has affected the sustainability of the crops and has deteriorated the biodiversity that provides ecosystem services such as biological control(CDB, 2010).

The natural enemies of pest populations are crucial in the context of sustainable agriculture because it provides benefits at an economic, social and environmental level (Gliess-mann, 2006; Thomson and Hoffmann, 2010). Among their natural enemies, parasitoids of the Hymenoptera order are particularly significant due to the specificity they have for their hosts. For this reason, they have been used extensively for biological control (Heraty, 2009). The idea is to consider the parasitoids that act naturally because they constitute model systems that provide benefits for natural control (Ehler, 1994) and do not represent the irreversible problems of exotic introductions (Haye et al., 2005; Basso and Grille, 2009).

The aim of this study was to determine the natural para-sitoid flies of the Dasiops genus and the relationship with four plant species of economically interesting Passiflora to estimate the trophic association between parasitoid, host, plant and the percentages of natural parasitism in the departments of Cundinamarca and Boyaca in Colombia.

Materials and methods

Study sitesProductive farms of passion fruit, purple passion fruit, sweet granadilla and banana passion fruit located in five municipalities of Cundinamarca and two municipalities of Boyaca were selected on records based on Dasiops spp., infestation. On each farm, samples were taken every 15 d for 17 months (Tab. 1). In all cases, the agronomic crop management was based on conventional chemical strategies. The geographical coordinates and altitude were determined by a global positioning system using GPS 40 Garmin device (Garmin, Schaffhausen, Switzerland).

Recovery of natural parasitoids and their association with each crop and Dasiops species

On each of the farms, 1 ha of the crop was selected to collect all floral buds and fruit infested by Dasiops spp., in accordance to specific symptoms of each species (Santamaría et al., 2014). These plant structures were placed separately in 30x40x15 cm white plastic containers, covered with 1 cm of sifted soil obtained from the crop and labelled flower bud traps (TB) or fruit traps (TF). Each trap was placed within the crop, 2 m from the edge in order to expose the larvae and pupae of the flies to the natural parasitoids (Tab. 1).

Every fortnight, the trap substrate was inspected to recover pupae of fruit flies. These were washed with clean water to remove adhering soil and pathogens and placed individually into plastic jars (10 cm in diameter x 6 cm high) containing 2 mm of sterilized river substrate sand and covered by a mesh top. The samples were maintained under controlled laboratory conditions to recover parasitoids that emerged. The conditions had an average temperature of 18°C, average relative humidity of 60% and a photoperiod of 12 h light/12 h dark.

The taxonomic identification of Dasiops species was based on morphological characters (Korytkowski, 2003) and Cheslavo Korytkowski from Panama University, as expert of this group, confirmed each one. Taxonomic classification of parasitoids was carried out based on morphological characteristics according to taxonomic keys and related scientific literature (Guimarães et al., 2003; Buffington and Ronquist, 2008; Sharkey and Wahl, 2006; Campos and Sharkey, 2006; Dix, 2009; Masner, 2006 a, b; Masner and García, 2002). Additionally, experts were consulted: Carlos Sarmiento of the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Unal (Institute of Natural Sciences), Bogotá; Paul Hanson, Professor at the Universidad de Costa Rica (University of Costa Rica) ; Marta Loiacono of the Museo de La Plata, Division Entomologia (La Plata Museum, Entomology Division), Argentina; and Valmir Antonio Costa of the Centro Experimental do Instituto Biologico Heitor Penteado (Heitor Penteado Experimental Centre of the Biological Institute) Campinasm, Brazil. The levels of parasitoid presence were analyzed according to the mortality rate, which compared the number of parasitoids with the number of adult flies of the Dasiops genus.

Results and discussion

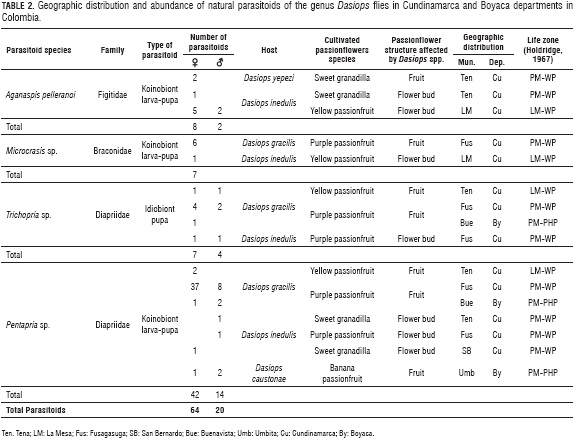

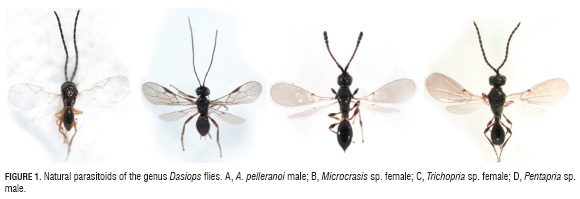

Parasitoids belonging to Braconidae, Diapriidae and Figitidae Hymenoptera families were recorded (Tab. 2). All of these are endoparasitoids of the Diptera immature stages (Fernández and Sharkey, 2006). Aganaspis pelleranoi (Bretes, 1924) (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) was found to be a parasitoid of pupae of D. yepezi and D. inedulis (Fig. 1A); parasitoids of pupae of D. inedulis and D. gracilis were found Microcrasis sp. Fischer, 1975 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Fig. 1B), Trichopria sp. Ashmead, 1893 (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) (Fig. 1C) and Pentapria sp. Kieffer, 1905 (Hy-menoptera: Diapriidae) (Fig. 1D). Pentapria sp., were found parasitizing D. caustonae in banana passionfruit.

A. pelleranoi was the first recorded instance of this species as a parasitoid of the genus Dasiops Rondani. This parasitoid emerged from pupae of D. inedulis and D. yepezi which infested flower buds of all Passiflora species evaluated and fruits of sweet granadilla, respectively (Tab. 2). However, A. pelleranoi is recognized as a koinobiont, endoparasitoid of larva and emerges in pupa, solitary, native to the Neotropics (Ovruski et al., 2000) parasitizing flies of the genus Neosilba (Diptera: Lonchaeidae) (Diaz and Gallardo, 2001) and, in several species of the genus Anastrepha (Nunes et al., 2012). The adult female is a forager; enters fruits infested by flies, seeks and detects larvae of the host through tactile exploration with antennae and tarsi, although it can be guided by chemical signals of plants (Guimarães and Zucchi, 2004; Aluja et al, 2009). Parasitism of D. yepezi could occur when larvae fall down from fruits to pupate on soil or pushing up from fallen flower buds by D. inedulis infestation.

A. pelleranoi presented variable percentage of parasitism in accordance to Dasiops species and cultivated passionflower species (Tab. 3). In D. inedulis infesting yellow passion fruit crops in La Mesa municipality, we registered 50 to 14% of parasitoidism, while just 4.17% was observed in the municipality of Tena (Tab. 3). In D. yepezi, as pest of sweet granadilla fruits, 4.2% parasitoidism was recorded. Sweet granadilla crops where this parasitoid was registered were characterized by having woodland in the periphery and flowering weeds within the growing area, characteristics that are advantageous for parasitoid populations, as they provide shelter and food (Hajek, 2004). Agro-ecosystems with greater diversity encourage the presence and activity of the parasitoid as observed on Anastrepha spp. where there was found an increase of 89.9% in shaded coffee productive systems (Souza et al., 2005). In this context, the results found in this study are important because, if A. pelleranoi can be found from Mexico to Argentina (Nunes et al., 2012), acting as generalist and oviposits regardless of the species of fly or host plant (Sivinski et al., 1997), this species could be found in other regions that produce sweet granadilla and passion fruit with infestations of D. inedulis and D. yepezi evaluated by Castro et al., (2012). As a koino-biont, allowing Dasiops to feed on plants during larvae stage, it is not a promising as biocontrol agent. However, A. pelleranoi is contributing to control of natural population of Dasiops inedulis and D. yepezi in Tena and La Mesa in the Cundinamarca Department, one of the more important areas to produce passion fruit crops.

Microcrasis sp., emerging from D. gracilis infested purple passion fruit and D. inedulis infested flower buds of passion fruit, is the first record as parasitoids of Dasiops spp. Because of seven putative species of Microcrasis being registered in Colombia (Dix, 2009), D. gracilis and D. inedulis have been listed in several municipalities of Antioquia, Tolima, Meta, Huila, Caldas, Quindío, Risaralda and Valle del Cauca, where these crops are settled; the geographical distribution of these wasps should be wider (Castro et al., 2012). Microcrasis spp., are endoparasitoids koinobiont (larva-pupa) of Tephritidae fruit flies (Núñez et al., 2009), solitaries (Dix, 2009) and, endemic from the Neotropics (Wharton, 1997).

Over three evaluations, the percentage of parasitism of Microcrasis sp., on D. inedulis was low (0.83%), where, as in D. gracilis. it was affecting purple passion fruit crops (3.13%) (Tab. 3). Parasitoids of the genus Microcrasis, are better suited to humid agro-ecosystems associated with plants that provide shade (Núñez et al., 2009), then it is possible that this kind of monoculture is not the best refuge for adults of this species (Speight et al., 2008) or, competence with other parasitoids, as A. pelleranoi occupying the same niche, is affecting the efficiency of Microcrasis as parasitoid of D. inedulis (Hajek, 2004).

Male and female of Trichopria spp., emerging from D. gracilis as pest as fruits of yellow and purple passion fruit and from D. inedulis as pest of flower buds of purple passion fruit, (Tab. 2) constitute the first record of wasps of this genus as parasitoids of Dasiops spp. Eleven specimens, nine emerged from the pupae of D. gracilis and two from D. inedulis, representing seven females and four males with a sex ratio of 1:0.57, were obtained. These wasps, recognized as parasitoids of Diptera, particularly in Tephritidae species (Souza-Filho et al., 2007), have broad distribution derived by parthenogenesis (Harms and Grodowitz, 2011).

Trichopria sp. had inconsistent percentages of parasitoidism (Tab. 3). Parasitoidism of 40% was recorded for D. inedulis in purple passion fruit while on D. gracilis, it ranged between 1.69% and 4.17 on purple passion fruit and 22% in yellow passion fruit (Tab. 3). This parasitoid is a gregarious idiobiont parasitoid infesting pupae of several species of Diptera (García and Corseuil, 2004). In this study, every specimen obtained emerged from a Dasiops spp. pupa, possibly because of the high availability of hosts in the environment and the size of the pupae (Basso and Grille, 2009). However, the population dynamic of this parasitoid, endemic to the Neotropics, could be affected by the introduction of non-native (exotic) Diptera hosts (Monteiro and Prado, 2000), by high rainfall and by the variable population of native hosts.

Although Pentapria sp. have been registered parasitizing D. inedulis of sweet granadilla crops (Santos et al., 2009), we are presenting first records as parasitoids of D. gracilis and D. inedulis in yellow and purple passion fruit of D. caustonae in banana passionfruit and, of D. inedulis infesting flower buds of purple passion fruit (Tab. 2). Forty- two females and fourteen males were found, representing a sex ratio of 1:0.33, characterizing the most abundant natural population of parasitoid found in five of the six municipalities evaluated in this study. Pentapria inhabits ecosystems of high mountains, cloud forests and tundra in Neotropics and Nearctic regions (Masner and García, 2002) and, it has been registered in Colombia between 150 to 3,660 m a.s.l. (Arias-Penna, 2003). However, information on the biology, habits and rates of parasitism by this species is unknown (Masner, 2006b).

Levels of parasitism of Pentapria sp. varied across three species of flies in the four crops. The highest percentage of parasitoidism was recorded in banana passionfruit, with 33.3% for D. caustonae infesting fruits. For D. gracilis, a pest of purple passion fruit fruits, the percentage or parasitism ranged 1.67 to 29.17%. However, as parasitoid of pest affecting flower buds in Passiflora, maximum parasitoidism recorded was 5.88% in sweet granadilla and 20% in purple passion fruit (Tab. 3). Pentapria sp., unlike A. pelleranoi, Microcrasis sp. and Trichopria sp., was found in all four cultivated species of Passiflora, from which it can be inferred that this is the most recurrent and abundant parasitoid of flies of the genus Dasiops.

D. inedulis has a broad distribution as it affects flower buds from sweet granadilla, yellow and purple passion fruit crops, occupying several life zones (Castro et al., 2012) in accordance to the Holdridge classification (Hold-ridge, 1967). For this pest, all families of the parasitoids (Aganaspis pelleranoi, Microcrasis sp., Trichopria sp., and Pentapria sp.) registered in this study, were found attacking D. inedulis. Additionally, there are more species acting as natural enemies to this fruit fly, as Basalys sp. (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae), Pachycrepoideus. vindem-miae (Rondani) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), Aspilota sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Bracon sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Orgilus sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Opius sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Santos et al., 2009; Chacón and Rojas, 1984; Ambrecht, 1985; Aguiar-Menezes et al., 2004). Coupled with cultural practices that promote the establishment of parasitoids in Passiflora crops, an integrated crop management can be established to further address D. inedulis, floral species causing early abortion affecting crop yields (Santamaría et al., 2014).

It is clear that the abundance of the host, characteristics of each production system (i.e stringing/wiring; density) but particularly, characteristics of the environment where crops are established, determine the abundance of natural enemies as parasitoids (Núñez et al., 2009; García and Corseuil, 2004). Additionally, the natural population of parasitoids, but particularly microparasitoids as belonging to Braconidae family, are affected by abiotic conditions as rainfall limiting their efficacy to localize their host (Núñez et al., 2009; Hance et al., 2007). In this context, landscape management, promoting shelter and foraging sites for adult parasitoids is crucial to maintaining the natural populations of the natural enemies associated with crop production systems (Straub et al., 2008; Landis et al., 2000).

Pentapria sp., showed wide geographical distribution as an idiobiont of pupae of Dasiops spp., in all of the assessed cultivated Passiflora species , despite the high pressure of selection by chemical control distributed at regular calendar intervals. This species has an important value as biocontrol of fruit flies in Passiflora crops; however, more studies are required to define its potential implementation. Collecting fallen flower buds and fruits infested by Dasiops spp. is important to truncate the life cycle of fruit flies and allow emergence of parasitoids. This simple cultural strategy could have important implications in reducing production costs, increased crop yields and environmental care.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (National University of Colombia) Bogotá campus, the Research Fund of the Faculty of Agronomy and the main campus of the Corporacion Universitaria Minuto de Dios (Minute of God Corporation University) and the Faculty of Engineering. Technical; scientific and logistical support were provided by the Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario ICA (Colombian Agricultural Institute) through the project "Adjustment, validation, and transfer of phytosa-nitary management technologies of the lonchaeid fly - Dasiops spp. (Diptera: Lonchaeidae), in Passiflora crops in Colombia" ASOHOFRUCOL code TR-1305. Sincere thanks are given to the following academics: Carlos Sarmiento, Professor at the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Unal (Institute of Natural Sciences) - Bogotá, Paul Hanson, Professor at the Universidad de Costa Rica (University of Costa Rica), Marta Loiácono, of the Museo de La Plata, División Entomología (La Plata Museum, Entomology Division)- Argentina and Dr. Valmir Antonio Costa, of the Centro Experimental do Instituto Biológico Rodovia Heitor Penteado (Experimental Centre of the Rodovia Heitor Penteado Biological Institute) Campinas - Brazil. We give special thanks to the Passiflora growers and cultivators who are the reason for this study. In memory of the scientific contributions of Professor Cheslavo Korytkowski. Many thanks to Rosie Holmes at Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand for her contribution to the English translation of this manuscript.

Literature cited

Aguiar-Menezes, E., R. Nascimento, and F. Menezes. 2004. Diversity of fly species (Diptera: Tephritoidea) from Passiflora spp. and their hymenopterous parasitoids in two municipalities of the southeastern Brazil. Neot. Entomol. 33, 113-116. Doi: 10.1590/ S1519-566X2004000100020. [ Links ]

Aluja, A., S.M. Ovruski, L. Guillén, L. Oroño, and J. Sivinski. 2009. Comparison of the host searching and oviposition behaviors of the tephritid (Diptera) parasitoids Aganaspis pelleranoi and Odontosema anastrephae (Hymenoptera: Figitidae, Eucoilinae). J. Insect Behav. 22, 423-451. Doi: 10.1007/s10905-009-9182-3. [ Links ]

Ambrecht, I. 1985. Biología de la mosca de los botones florales del maracuyá Dasiops inedulis (Diptera. Lonchaeidae). Undergraduate thesis. Faculty of Sciences, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. [ Links ]

Arias-Penna, T. 2003. Lista de los géneros y especies de la superfamilia Proctotrupoidea (Hymenoptera) de la región Neotropical. Biota Colomb. 4, 3-32. [ Links ]

Basso, C. and G. Grille (eds.). 2009. Relaciones entre organismos en los sistemas hospederos-parasitoides-simbiontes. Horticultura 211, 34-35. [ Links ]

Buffington, M. and F. Ronquist. 2008. Familia Figitidae. pp. 829-838. In: Fernández, F. and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). 2006. Introducción a los Hymenoptera de La Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Campos, D. and M. Sharkey. 2006. Familia Braconidae. pp. 331-384. In: F. Fernández y M.J. Sharkey (eds.). 2006. Introducción a los Hymenoptera de La Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Castro, A., A. Sepúlveda, C. Vallejo, C. Korytkowski, E. Ebratt, H. Brochero, H. Gómez, J. Salamanca, M. Santamaría, M. Cubides, M. González, O. Martínez, S. Parada, and Z. Flores. 2012. Moscas de género Dasiops Rondani 1856 (Diptera: Lonchaeidae) en cultivos de pasifloras. Technical Bulletin. Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA), Bogotá [ Links ].

Chacón, P. and M. Rojas. 1984. Entomofauna asociada a Passiflora mollissima, P. edulis, P. flavicarpa y P. quadrangularis en el departamento del Valle del Cauca. Turrialba 34, 297-311. [ Links ]

CDB, Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica. 2010. Document Unep/CBD/94/1 Río de Janeiro, Brasil. In: https://www.cbd.int/; consulted: November, 2015. [ Links ]

Diaz, N. and F. Gallardo. 2001. Aganaspis Lin 1987. generic enlargement and a key for species present in a Neotropical region (Cynipoidea: Figitidae: Eucoilinae). Phycis 58, 91-95. [ Links ]

Dix, O.J. 2009. Sinopsis de las especies de la subfamilia Alysiinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) en Colombia. MSc thesis. Faculty of Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Ehler, L. 1994. Parasitoid communities, parasitoid guilds, and biological control. pp. 418-436. In: Hawkins, B.A. and W. Sheehan (eds.). Parasitoid community ecology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. [ Links ]

Fernández, F. and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). 2006. Introducción a los Hymenoptera de la Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

García, F. and E. Corseuil. 2004. Native hymenopteran parasitoids associated with fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fla Entomol. 87, 517-521. Doi: 10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087[0517:NHPAW F]2.0.CO;2. [ Links ]

Gliessmann, S. 2006. Agroecology: the ecology of sustainable food systems. 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [ Links ]

Guimarães, J., F. Gallardo, N. Diaz, and R. Zucchi. 2003. Eucoilinae species (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea: Figitidae) parasitoids of fruit-infesting dipterous larvae in Brazil: identity, geographical distribution and host associations. Zootaxa 278, 1-23. Doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.278.1.1. [ Links ]

Guimarães, J.A. and R.A. Zucchi. 2004. Parasitism behavior ofthree species of Eucoilinae (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea, Figitidae) parasitoids of fruit flies (Diptera). Neot. Entomol. 33, 217-224. Doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2004000200012. [ Links ]

Hajek, A. 2004. Natural enemies: an introduction to biological control. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. Doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511811838. [ Links ]

Hance, T., J. van Baaren, P. Vernon, and G. Boivin. 2007. Impact of extreme temperatures on parasitoids in a climate change perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52, 107-26. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091333. [ Links ]

Harms, N. and M. Grodowitz. 2011. Overwintering biology of Hydrellia pakistanae (Diptera: Ephydridae), biological control agent of Hydrilla. J. Aquatic Plant Manage. 49, 114-117. [ Links ]

Haye, T., A. Broadbent, J. Whistlecraft, and U. Kuhlmann. 2005. Comparative analysis of the reproductive biology of two Peri-stenus species (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), biological control agents of Lygus plant bugs (Hemiptera: Miridae). Biol. Control 32, 442-449. Doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.11.004. [ Links ]

Heraty, J. 2009. Parasitoid biodiversity and insect pest management. pp. 445-462. In: Foottit, R.G. and P.H. Adler (eds.). Insect biodiversity: science and society. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK. Doi: 10.1002/9781444308211.ch19. [ Links ]

Holdridge, L.R. 1967. Life zone ecology. Tropical Science Center, San Jose. [ Links ]

Korytkowski, C. 2003. Manual de identificación de moscas de la fruta. Parte 1: Generalidades sobre clasificación y evolución de Acalyptratae, familias Neriidae, Ropalomeridae, Lonchaeidae, Richardiidae, Otitidae y Tephritidae. Master Program in Entomology, Universidad de Panamá, Transistmica, Panama. [ Links ]

Landis, D., S. Wratten, and G. Gurr. 2000. Habitat management to conserve natural enemies of arthropod pests in agriculture. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45, 175-201. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.175. [ Links ]

MADR, Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. 2015. Agronet. Análisis y estadísticas. In: www.agronet.gov.co; consulted: February, 2016. [ Links ]

Masner, L. 2006a. Superfamilia Proctotrupoidea. pp. 609-612. In: Fernández, F. and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). Introducción a los Hymenoptera de la Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Masner, L. 2006b. Familia Diapriidae. pp. 615 - 618. In: Fernández, F. and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). Introducción a los Hymenoptera de La Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Masner, L. and J.L. García. 2002. The genera of Diapriinae (Hy-menoptera: Diapriidae) in the New World. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 268, 138. [ Links ]

Monteiro, M. and E. Do Prado. 2000. Ocorrência de Trichopria sp. (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) atacando pupas de Chrysomya putoria (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) na granja. An. Soc. Entomol. Brasil. 29, 159-167. Doi: 10.1590/ S0301-80592000000100020. [ Links ]

Nunes, A., F. Appel, R. Da Silva, M. Silveira, V. Costai, and D. Nava. 2012. Moscas frugívoras e seus parasitoides nos municípios de Pelotas e Capão do Leão, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciênc. Rural 42, 6-12. Doi: 10.1590/S0103-84782012000100002. [ Links ]

Núñez, L., R. Gómez, G. Guarín, and G. León. 2009. Moscas de las frutas (Díptera: Tephritidae) y parasitoides asociados con Psidium guajava L. y Coffea arabica L. en tres municipios de la Provincia de Vélez (Santander, Colombia). Corpoica Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 5, 5-12. [ Links ]

Ovruski, S., M. Aluja, J. Sivinski, and R. Wharton. 2000. Hymenopteran parasitoids on fruit-infesting Tephritidae (Diptera) in Latin America and the southern United States: diversity, distribution, taxonomic status and their use in fruit fly biological control. Int. Pest Manage. 5, 81-107. [ Links ]

Santamaría, M., E. Ebratt, E. Brochero, and A. Castro. 2014. Caracterización de daños de moscas del genero Dasiops (Diptera: Lonchaeidae) en Passiflora spp. (Passifloraceae) cultivadas en Colombia. Rev. Fac. Nal. Agr. Medellín 67, 7151-7162. Doi: 10.15446/rfnam.v67n1.42605. [ Links ]

Santos, A., E. Varón, and J. Salamanca. 2009. Prueba de extractos vegetales para el control de Dasiops spp. en granadilla (Passiflora ligularis Juss) en el Huila, Colombia. Corpoica Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 10, 141-151. [ Links ]

Sharkey, M. and D. Wahl. 2006. Superfamilia Ichneumonoidea. pp. 287-292. In: Fernández, F. and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). 2006. Introducción a los Hymenoptera de La Región Neotropical. Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá [ Links ].

Sivinski, J., M. Aluja, and M. López. 1997. Spatial and temporal distributions of parasitoids of Mexican Anastrepha species (Diptera: Tephritidae) within the canopies of fruit trees. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 90, 604-618. Doi: 10.1093/aesa/90.5.604. [ Links ]

Souza, S., A. Resende, P. Strikis, J. Costa, M. Ricci, and E.E. Aguiar-Menezes. 2005. Infestação natural de moscas frugívoras (Diptera: Tephritoidea) em café arábica, sob cultivo orgânico arborizado e a pleno sol, em Valença, RJ. Neotrop. Entomol. 34, 639-648. Doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2005000400015. [ Links ]

Souza-Filho, Z., E. de Araujo, J. Guimarães, and J. Gomes. 2007. Endemic parasitoids associated with Anastrepha spp. (Diptera: Tephritidae) infesting guava (Psidium guajava) in southern Bahia, Brazil. Fla. Entomol. 90, 783-785. Doi: 10.1653/0015-4040(2007)90[783:EPAWAS]2.0.CO;2. [ Links ]

Speight, M., M. Hunter, and A. Watt. 2008. Ecology of the insects: concepts and applications. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK. [ Links ]

Straub, C., D. Finke, and W. Snyder. 2008. Are the conservation of natural enemy biodiversity and biological control compatible goals? Biol. Control 45, 225-237. Doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.05.013. [ Links ]

Thomson, L.J. and A. Hoffmann. 2010. Natural enemy responses and pest control: Importance of local vegetation. Biol. Control 52, 160-166. Doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.10.008. [ Links ]

Wharton, R.A. 1997. Alysiinae. pp. 85-18. In: Wharton, R.A., P.M. Marsh, and M.J. Sharkey (eds.). Manual of the New World genera of the family Braconidae (Hymenoptera). International Society Hymenoptera, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Wyckhuys, K., C. Korytkowski, J. Martínez, B. Herrera, A.M. Rojas, and J. Ocampo. 2012. Species composition and seasonal occurrence of Diptera associated with passionfruit crops in Colombia. Crop Prot. 32, 90-98. Doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2011.10.003. [ Links ]