OVER THE last few decades, increasing attention has been given to the effects of personality traits, or dispositions, on individuals' attitudes and behavior in the workplace (Judge, Klinger, Simon, & Yang, 2008; Ones, Dilchert, Viswesvaran, & Judge, 2007). Job satisfaction in particular, which reflects the extent to which employees like their jobs (Fritzsche & Parrish, 2005), is one of the most studied phenomena within this research stream (Judge, Weiss, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Hulin, 2017). This special interest in job satisfaction partly reflects the scholarly and managerial concerns to improve employees' attitudes in the workplace, as they have been found to significantly affect both organizational effectiveness and well-being levels (Diestel, Wegge, & Schmidt, 2014; Faragher, Cass, & Cooper, 2005; Flickinger, Allscher, & Fiedler, 2016; Grant, Wardle, & Steptoe, 2009; Harrison, Newman, & Roth, 2006; Tsaousis, Nikolaou, Serdaris, & Judge, 2007).

From a dispositional perspective, individuals possess a set of relatively stable (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Dormann, Fay, Zapf, & Frese, 2006) and often genetically traceable (Johnson, McGue, & Krueger, 2005; Judge, Ilies, & Zhang, 2012), unobservable mental states or dispositions that significantly affect their attitudes and behavior in the workplace (Judge, Klinger, et al., 2008). Indeed, the dispositional approach helps to explain why people tend to have a more positive or negative attitude across a variety of domains (Judge et al., 2017). In this regard, several studies have consistently demonstrated the effects of different personality taxonomies on employees' job satisfaction in various organizational settings (for a review, see Pujol-Cols & Dabos, 2018). Although most personality research has been conducted under the framework of the Big Five Personality Traits, two decades ago, Judge, Locke, Durham, and Kluger (1998) also introduced a relatively stable, broad, and higher-order concept named Core Self-Evaluations (CSES). CSES consist of a set of basic and fundamental conclusions that individuals make about their self-worth and capabilities and reflect four well-established traits in psychology, namely, self-esteem, self-efficacy, internal locus of control, and emotional stability (Judge, Klinger et al., 2008).

Prior studies have revealed substantial intercorrelations (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, 2002) and a one-factor structure underlying the four aforementioned traits (Judge, Bono, & Locke, 2000), which motivated Judge, Erez, Bono, and Thoresen (2003) to develop a more direct and economic measure of CSES, named Core Self-Evaluations Scale (CSES). In regard to the effects of CSES on job satisfaction, previous studies have consistently shown that the CSE concept (as measured with the CSES) seems to explain incremental variance in job satisfaction beyond its four specific core traits (Piccolo, Judge, Takahashi, Watanabe, & Locke, 2005). Moreover, other studies (e.g., Judge, Heller, & Klinger, 2008; Rode, Judge, & Sun, 2012; Stumpp, Muck, Hülsheger, Judge, & Maier, 2010) have also demonstrated that CSES seem to explain incremental variance in job satisfaction, beyond other dispositional measures (e.g., Big Five Personality Traits), suggesting that the CSE construct may be the best dispositional predictor of job satisfaction (Judge, Van Vianen, & De Pater, 2004).

Despite the growing empirical evidence supporting the positive effects of CSES on job satisfaction (Hsieh & Huang, 2017; Judge, Klinger et al., 2008; Stumpp et al., 2010; Wu & Griffin, 2012; Yan, Yang, Su, Luo, & Wen, 2016), organizational psychology research has only begun to explore the mechanisms and processes underlying the CSES - job satisfaction link (Heller, Ferris, Brown, & Watson, 2009). Yet, only a few mediators have been examined in the literature, including, for instance, perceptions of intrinsic work characteristics (Judge et al., 2000), job complexity (Judge et al., 2000), task complexity (Srivastava, Locke, Judge, & Adams, 2010), self-concordance (Judge, Bono, Erez, & Locke, 2005), work personality (Heller et al., 2009), emotional intelligence (Shi, Yan, You, & Li, 2015; Yan et al., 2016), coping mechanisms (Kammeyer-Mueller, Judge, & Scott, 2009), organizational commitment (Peng et al., 2014), vocational identity (Hirschi, 2011), and strain (Judge et al., 2012).

Regarding the mediating role of job characteristics in particular, previous studies conducted in Anglo-Saxon contexts have suggested that employees with higher CSES tend to perceive and experience their job in a more positive way (i.e., CSES seem to enhance individuals' appraisals of work situations), which, in turn, has been found to be associated with increasing job satisfaction (Cohrs, Abele, & Dette, 2006; Judge et al., 2017; Judge et al., 2000). On the contrary, those individuals with lower CSES tend to perceive their job as more stressful, which is likely to lead to the experience of strain and job dissatisfaction (Brunborg, 2008; Harris, Harvey, & Kacmar, 2009; Judge et al., 2012; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2009; Kluemper, 2008; Sunal, Sunal, & Yasin, 2011). In spite of this evidence, research on the mediating effects of job characteristics has produced inconsistent results (see Chang, Ferris, Johnson, Rosen, & Tan, 2012; Hsieh & Huang, 2017), suggesting that more research efforts are needed in order to improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the CSES - job satisfaction relationship. Moreover, the majority of prior studies on this matter have focused on a relatively narrow set of intrinsic work factors (i.e., those relating to the individual's tasks; e.g., Hackman & Oldham, 1976), neglecting, to a considerable extent, the effects of extrinsic work factors (i.e., those relating to the organizational, social, and physical conditions in which tasks are performed) that are also highly relevant for explaining individuals' job satisfaction (Dierdorff & Morgeson, 2013; Ferguson & Cheek, 2011; Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

In this study, we include one measure of intrinsic work characteristics, namely, autonomy, and three measures of extrinsic work characteristics, namely, social support from colleagues and leaders, esteem, and job security. All of these factors have proven to play a vital role in explaining job satisfaction in the past literature. For instance, since autonomy is a basic universal psychological need, it is expected to nourish individuals' intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014). Indeed, previous studies (e.g., Ferguson & Cheek, 2011) have suggested that autonomy represents one of the strongest situational predictors of employees' job satisfaction. Social support from colleagues and leaders, which reflects "the degree to which a job provides opportunities for advice and assistance from others" (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006, p. 1324), has also been found to play a vital role in explaining individuals' job satisfaction levels (Cortese, Colombo, & Ghislieri, 2010; Kinman, Wray, & Strange, 2011), especially under highly stressful working conditions (Wrzesniewski, Dutton, & Debebe, 2003). In regard to the effects of esteem, previous findings have revealed that the extent to which employees believe that rewards such as pay, recognition, or career opportunities are fairly distributed in the organization plays a significant role in their job satisfaction (Danish & Usman, 2010). Finally, job security, that is to say an individual's prolonged certainty about the continuity of his current job situation, has been suggested to be a vital antecedent of job satisfaction (Reisel, Probst, Chia, Maloles, & Kõnig, 2010), as working is highly instrumental for fulfilling both basic and superior needs (Weir, 2013; Zhang, Wu, Miao, Yan, & Peng, 2014).

From Judge et al. (1998)'s seminal contributions to this day, CSES have been given considerable attention in dispositional research. Indeed, they have been studied in several organizational settings and countries, including the United States (Judge, Heller et al., 2008), Israel (Judge et al., 1998), Spain (Judge et al., 2004), Japan (Piccolo et al., 2005), Greece (Nikolaou & Judge, 2007), The Netherlands (Judge et al., 2004), Germany (Stumpp et al., 2010; Dormann et al., 2006), Poland (Walczak & Derbis, 2015), Iran (Karatepe, 2011; Sheykhshabani, 2011), France (Nguyen & Borteyrou, 2016), Taiwan (Hsieh & Huang, 2017), New Zealand (Bowling, Wang, & Li, 2012), Korea (Holt & Jung, 2008), and China (Guo, Zhu, & Zhang, 2017; Liu, Li, Ling, & Cai, 2016). Regarding the Argentinian context in particular, it should be noted that some previous studies have successfully linked either the CSE construct (Pujol-Cols & Dabos, 2017; Pujol-Cols & Dabos, in press) or some of its individual traits (e.g., self-efficacy; see Salessi & Omar, 2017) to job satisfaction. However, to our knowledge, no previous study has explored the indirect effects of the CSE construct on job satisfaction in Argentina.

With the aim of advancing our understanding of this relatively unexplored field of studies, especially in Argentina, this article analyzes the mediating effects of perceived job characteristics on the relationship between CSES and job satisfaction by using data collected from two independent samples of highly skilled workers. Our study builds on the earlier work of Judge et al. (1998, 2000), among others, and makes two additional contributions. First, it extends the CSE model by examining the role of three factors relating to the work environment (i.e., extrinsic work characteristics), namely, social support from colleagues and leaders, esteem, and job security, in the CSES - job satisfaction link, as prior studies have mostly focused on the effects of intrinsic job characteristics (e.g., task significance). Second, this is the first study to explore the mediating effects of job characteristics on the relationship between CSES and job satisfaction in a Latin-American context. Therefore, it intends to provide evidence of the universality and cross-cultural validity of the CSE construct.

Based on the previous findings that suggested that CSES tend to enhance individuals' appraisals of work situations, which is likely to lead to higher intrinsic motivation, decreasing experienced strain, and, therefore, increasing job satisfaction (Brunborg, 2008; Cohrs et al., 2006; Harris et al., 2009; Judge et al., 2000, 2012, 2017; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2009; Kluemper, 2008; Sunal et al., 2011), we set the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H-1). Main effects: CSES will be independently related to job satisfaction. In other words, those employees with more positive self-regards will be more satisfied with their jobs.

Hypothesis 2 (H-2). Mediation effects: Perceptions of job characteristics will partly mediate the effects of CSES on job satisfaction. In other words, those employees with higher CSES will perceive their jobs in a more positive way and, as a result, will experience increasing job satisfaction.

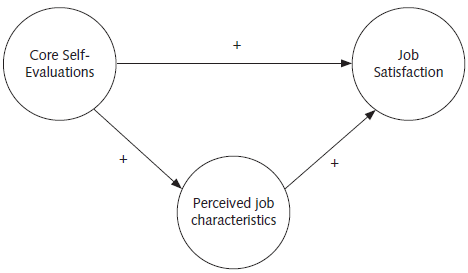

Figure 1 displays the hypothesized model linking CSES, perceived job characteristics, and job satisfaction. The model states that the effects of CSES on job satisfaction are partially mediated by perceptions of job characteristics.

Figure 1 Hypothesized model linking core self-evaluations, perceptions of job characteristics, and job satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

To increase the generalizability of our findings, we collected data in two independent samples. Since the majority of previous studies on the effects of CSES have used samples consisting of undergraduate students or unskilled workers, we selected two samples of highly skilled professionals.

Sample 1. Participants were a non-random sample of scholars from an Argentinian university. We first contacted the academic authorities of the university and, after agreeing on the research design, survey administration, and time requirements, we obtained clearance for sending online invitations and a link to an online survey to 913 academics. A total of 190 complete surveys were filled out, representing a 20.81 % overall response rate. The age of the respondents ranged from 23 to 70, with a mean (standard deviation in parenthesis) of 44.39 (11.64) years. About 70 % of the participants were female, 36.32 % were professors, and 24.64 % had full-time jobs. The tenure of the respondents ranged from 1 to 43, with a mean of 17.45 (10.54) years. Only complete answers were accepted when submitting the survey.

Sample 2. Participants were a non-random sample of 241 graduate students enrolled in a part-time Master of Business Administration (MBA) program. All of the potential participants held managerial positions in medium-sized companies from different industries. Invitations were sent by e-mail through the coordinators of the MBA program, along with a description of the purposes of the study. Students interested in participating in the study were asked to sign a consent form and fill out an online survey. A total of 125 students completed the online survey. Nine cases were eliminated due to excessive missing values, resulting in a 41.49 % response rate (N=H6, no missing values). The age of the respondents ranged from 22 to 65, with a mean of 36.57 (8.89) years. About 62 % of the participants were male, 55.17 % were married, and 71.55 % had full-time jobs.

Variables and Instruments

Core self-evaluations. A Spanish version of the Core Self-Evaluations Scale (CSES; Judge et al., 2003) was used to assess the CSES. It is worth mentioning that the Spanish version of the CSES has exhibited appropriate psychometric properties in the Argentinian context (see Pujol-Cols, 2018; Pujol-Cols & Dabos, 2017, in press), including content validity, linguistic and cultural equivalence, internal consistency (a=.80), factor structure (fit statistics for the unidimensional model, CFI=.88, GFI=.92, RMSEA=.07), convergent validity (factor loadings>.40), and empirical validity (observed correlation between the CSES and job satisfaction=.40, p<.01). This version maintained the 12-item structure of the original scale, with a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except for reverse scored items.

Overall job satisfaction. Overall job satisfaction was measured with a Spanish version of the Brief Index of Affective Job Satisfaction (BIAJS; Thompson & Phua, 2012). This version has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in the Argentinian context (see Pujol-Cols, 2018; Pujol-Cols & Dabos, 2017, in press), including content validity, linguistic and cultural equivalence, internal consistency (a=.83), factor structure (fit statistics for the unidimensional model, CFI=.97, GFI=.97, RFI=.90, TLI=.91), and convergent validity (factor loadings>.65). The Spanish version of the BIAJS maintained the 4-item structure of the original scale, with a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Perceived job characteristics. We measured employees' perceptions with various aspects of their job using scales taken from the COPSOQ-ISTAS 21 (version 1.5; Moncada & Llorens, 2004). Specifically, we selected scales measuring job characteristics that we hypothesized to be key determinants of individuals' job satisfaction. These scales were: (a) Autonomy (10 items, including "my opinion is taken into account when tasks are assigned to me"), (b) Social support from colleagues and leaders (10 items, including "I am given all the information I need for doing my job properly"), (c) Esteem (4 items, including "my superiors acknowledge my work in the way I deserve"), and (d) Job security (4 items, including "I am worried about the possibility of getting fired", reverse scored). Responses for all four scales were anchored on a 5-point scale, with responses ranging from 0 (never/to a very small extent) to 4 (always/to a very large extent), except for reverse scored questions, reflecting the degree or frequency with which participants experience various situations related to the subscale. It is worth mentioning that the COPSOQ-ISTAS 21 has been validated in several Latin-American countries (Alvarado et al., 2009, 2012; García et al., 2016) and, particularly, has shown acceptable psychometric properties in the Argentinian context (Gerke et al., 2016; Pujol-Cols & Arraigada, 2017). Consistently with previous research using the same instrument (Mudrak et al., 2018; Pujol-Cols & Lazzaro-Salazar, 2018), the total score for each core dimension was averaged individually.

Analysis

We conducted descriptive and correlational analyses as a preliminary step. The internal consistency of each scale was also calculated (Cronbachs alpha). To test our hypotheses, we conducted structural equation modeling analyses with latent and observed variables in IBM amos (version 22), using a maximum-likelihood estimation method. The hypothesized model included one exogenous latent variable (i.e., CSES) and two endogenous latent variables (i.e., perceived job characteristics and job satisfaction). Regarding model specification, we followed Bagozzi & Edwards (1998)' recommendation to use partial disaggregation models. Therefore, instead of including all 12 items of the CSES as indicators of the latent CSE construct, we formed two parcels by combining the first six and the last six items of the scale. The same strategy was used for the job satisfaction latent factor. The indicators of the perceived job characteristic latent factor were the average scores of autonomy, social support from colleagues and leaders, esteem, and job security. We followed Byrne (2001)'s recommendation to use and compare several fit statistics, such as: Chi-square (x2), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (cif), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). As suggested by Byrne (2001), CIF , GFI , and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA values as high as .08 indicate a satisfactory fit.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

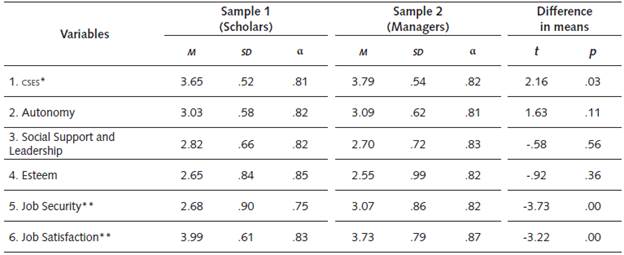

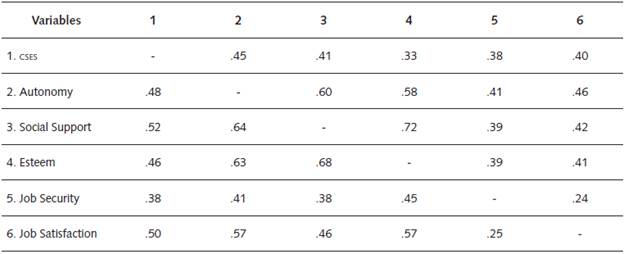

Descriptive statistics and reliabilities for each of the variables measured in both samples are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, many of the scale means were significantly different across the two samples. Overall, CSES were higher and job satisfaction was lower in the manager data set (CSES=3.79, job satisfaction=3.73) than in the scholar data set (CSES=3.65, job satisfaction=3.99). Moreover, scholars seemed to experience lower job security (M=2.68) than managers («=3.07). That the dispositions, job satisfaction, and perceptions of job characteristics were significantly different across the two samples argued against combining them for the analysis. Therefore, we decided to analyze both samples separately.

Correlations among the variables of study for the two samples are reported in Table 2. Consistently with previous research, CSES displayed a positive, non-zero relationship with overall job satisfaction across the two samples. Moreover, they exhibited positive and statistically significant relationships with perceptions of job characteristics, such as autonomy, social support, esteem, and job security. These findings may suggest that those employees with more positive self-regards (i.e., with higher CSES) tend to perceive their working conditions as more resourceful. In addition, the four job characteristics included in this study displayed positive, non-zero relationships with overall job satisfaction, meaning that perceptions of better working conditions are associated with higher levels of job satisfaction.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Scale Reliabilities for Two Samples

Note: *Means are significantly different between groups at the p<.05 level (two tailed), ** Means are significantly different between groups at the p<.01 level (two tailed).

Table 2 Correlations among Variables for the Scholar and Manager Samples

Note: CSES = Core Self-Evaluations. All reported correlations are statistically significant at the p<.01 level. Correlations from scholar data set (w=190) are indicated above the principal diagonal. Correlations from manager data set (W=116) are indicated below the diagonal.

Structural models

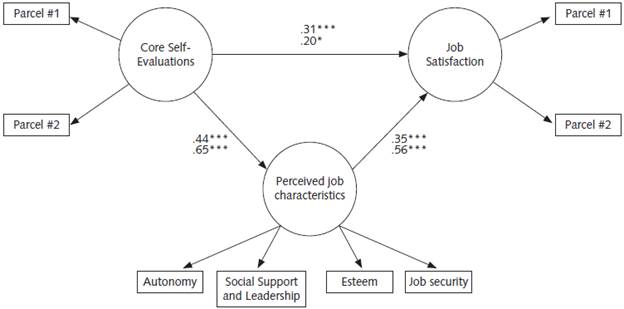

To test our hypotheses, we used structural equation modeling to estimate a series of models in amos (version 22). As a preliminary step, we tested for multivariate normality by conducting the Mardia test (see Mardia, 1985). Results showed that the data did not conform to multivariate normality (see Bentler, 2006). Therefore, we used the Bollen-Stine bootstrap method (1,000 bootstrap samples) to correct the p-values for the chi-square test (see Bollen & Stine, 1992). Figure 2 reports the standardized estimates for the hypothesized model that relates CSES, perceived job characteristics, and job satisfaction. The fit statistics were very similar across samples, showing in both cases a satisfactory fit to the data, Scholar sample: X 2 (df=17, n=190)=43.06, p<.01, CFI=.96, GFI=.95, TLI=.93, RMSEA=.09; Manager sample: X2(df =17, AT=H6)=23.08, p>.10, CFI=.99, GFI=.96, TLI=.98, RMSEA=.05. The results showed that CSES had a direct, positive, and statistically significant relationship with job satisfaction, supporting H-1.

Figure 2 Relationships among core self-evaluations, perceived job characteristics, and job satisfaction. Estimates in first row represent results from scholar data set, estimates in second row represent results from MBA student data set. ***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10

H-2 stated that the relationship between CSES and job satisfaction would be mediated by perceived job characteristics. Table 3 presents the direct, indirect, and total effects of CSES on job satisfaction for both samples. To further examine the significance of these effects, we created 1,000 bootstrap samples using the Montecarlo method in amos (version 22). As the table shows, the total effects of CSES on job satisfaction were relatively strong across samples, although the direct relationship was found to be stronger in Sample 1 than in Sample 2. Results also indicated a significant indirect relationship between CSES and job satisfaction across the two samples. These results provided support to H-2, thus showing that most of the significant relationship between CSES and job satisfaction was partly mediated by perceived job characteristics.

Discussion

For over two decades, studies have consistently demonstrated the relevance of CSES in understanding job satisfaction (Judge & Zapata, 2015; Judge et al., 2017; Ones et al., 2007). Drawing on the earlier work of Judge et al. (1998, 2000, 2010), this article examined the mediating role of perceived job characteristics in the relationship between CSES and job satisfaction in two independent samples of highly skilled professionals in Argentina, thus making three additional contributions to the literature. First, this was the first study to explore the indirect effects of CSES on job satisfaction in a Latin-American context. Second, this article provided evidence from two occupational contexts in which CSES have been limitedly explored, as the majority of previous studies on this matter have used samples consisting of undergraduate students or unskilled workers. Third, since previous research on the relationships among CSES, job characteristics, and job satisfaction have mainly focused on the effects of intrinsic work characteristics (i.e., those relating to the employees' tasks), the present study also examined the role of three factors relating to the work environment (i.e., extrinsic job characteristics), namely, social support from colleagues and leaders, esteem, and job security, in an attempt to extend the CSE model.

In regard to the effects of CSES on job satisfaction, our results revealed that part of these effects are direct. Judge et al. (1998) explained this relationship by stating that "core self-evaluations are the base on which situationally specific appraisals occur" (p. 31), meaning that those individuals with higher CSES tend to have the personal resources that allow them to see and evaluate the different domains of their lives in a more positive way. Consequently, those individuals with higher CSES are most likely to feel satisfied with their jobs since they: (a) have higher self-esteem and, therefore, tend to see themselves as worthy of happiness; (b) have higher self-efficacy, which means that they have a strong confidence in their capabilities to overcome the challenging aspects of their job; (c) have an internal locus of control and, as a result, tend to attribute the most positive outcomes of their jobs to their own effort and merit; (d) are low in neuroticism, meaning that they are less likely to focus on their shortcomings as well as on the negative aspects of their jobs (Srivastava et al., 2010). Since our results were consistent with those reported in North-American, Asian, and European contexts, this study provides further support to the universality and cross-cultural validity of the CSE construct.

Our results also showed that part of the effects of CSES on job satisfaction are indirect, as they are partially mediated by perceptions of job characteristics (32% in Sample 1 and 65% in Sample 2). This evidence suggests that those individuals with more positive CSES are more likely to feel satisfied not only because they believe that they are capable, worthy, and in control of events, but also because they tend to perceive their jobs as more secure, rewarding, and supportive. Indeed, the results of this study demonstrated that CSES play a significant role in the way employees perceive, experience, and react to the events that they face in the workplace, which is consistent with previous studies conducted in other contexts (Judge et al., 1998; Judge et al., 2000; Judge et al., 2012; Laschinger, Nosko, Wilk, & Finegan, 2014; Srivastava et al., 2010). Following Bakker and Demerouti (2014), those individuals who perceive their jobs as more resourceful are most likely to experience positive states, such as higher job satisfaction, as job resources tend to boost employees' growth, learning, and development through motivational processes. Moreover, since job resources also play a significant role in mitigating the detrimental effects of job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014), it is highly likely that those individuals who perceive job characteristics as more stressful tend to experience increasing strain and, in turn, lower levels of job satisfaction (Brunborg, 2008; Judge et al., 2012; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2009). Future studies should further address these mechanisms by including direct measures of stress, strain, and coping strategies.

Implications for Practice

Our results have several practical implications. On the one hand, since individuals with higher CSES tend to bring a more "positive frame" to the situations and events that happen in their lives, they are more likely to perceive and experience the attributes of their jobs more positively. Therefore, by considering themselves as more capable, worthy, and in control of situations and by viewing their jobs as more resourceful, they are also more likely to experience positive states such as job satisfaction. On the other hand, our results make us wonder whether some management strategies attempting to increase job satisfaction may be ineffective for those employees with low CSES. Thus, we believe that organizations should carefully evaluate the personality traits of candidates during personnel selection, while also designing new strategies for enhancing some of the least stable personality traits of their current employees.

Limitations of the study

In spite of the contributions that our study makes, it also presents some limitations that are worth mentioning. First, the three variables included in our study were measured at the same time, which may cause common-method bias. This concern was addressed by conducting the Harman's one-factor test. The results revealed that one single factor accounted only for 22.78% of the variance in Sample 1 and 22.42% in Sample 2, suggesting that the common-method bias did not affect our results (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Second, our models were estimated using cross-sectional data, which means that the causality of the proposed relationships cannot be drawn. Indeed, in the same way as we hypothesized that higher CSES tend to enhance individuals' perceptions of job characteristics, which, in turn, increases their job satisfaction, reverse causality is also possible. In this regard, numerous studies have proposed that more positive working conditions (i.e., more resourceful), such as a supportive organizational climate, tend to activate positive personality traits (e.g., Gooty, Gavin, Johnson, Frazier, & Snow, 2009; Luthans, Norman, Avolio, & Avey, 2008). Third, it could also be argued that the two samples included in our study were too homogeneous, as both consisted of highly skilled employees. We believe that future studies should further test our models by using more heterogeneous samples of employees, who are exposed to a wider range of working conditions. Finally, our research only included one personality trait (i.e., the CSE composite) and used self-report scales. Future studies should also examine CSES by using other techniques, such as peer-review ratings and in-depth clinical interviews.