The genus Pelliciera Triana and Planchon (1862), family Tetrameristaceae, is part of neotropical mangrove ecosystems, considered endemic to the tropical Pacific coast of the Americas until 1982 (Calderón-Sáenz, 1982). In the Colombian Caribbean, it was first reported in estuarine systems in the Bolívar department (Calderón-Sáenz, 1982, 1983, 1984), and subsequently in Córdoba (Sánchez et al., 1997; Castillo-Cárdenas et al., 2015) and Antioquia (Blanco Libreros et al., 2016). In the Caribbean, the presence of populations of this mangrove has been reported in other countries such as Nicaragua (Roth and Grijalva, 1991) and Panama (Duke et al., 1997; Dangremond and Feller, 2014).

Pelliciera was long considered a monotypic genus, with P. rhizophorae as sole representative, and according to fossil records, it is the oldest mangrove species in the Neotropics (Graham, 1977; Duke, 2020). However, Triana and Planchon (1962) and Calderón-Sáenz (1982) described some individuals of this species as a variety (P. rhizophorae var. benthamii), which, based on recent genetic, ecological, and morphological evidence, such as flower color and dimensions, bracteole characteristics, and the presence of dentition on leaf margins (Castillo-Cárdenas et al., 2015; Garzón et al., 2018; Duke, 2020), has been elevated to species status and lectotypified (Cornejo and Bonifaz, 2020), restructuring the genus into two species: P. rhizophorae Triana and Planchon and P. benthamii (Triana and Planchon, 1862) Cornejo.

The similarity between these two species and their evolutionary history related to the emergence of the isthmus of Panama need scientific study on their morphological characteristics, the status of their populations at the local level, and their vulnerability at a global scale. With the support of integrative taxonomy, we address these uncertainties and debates about the existence of one or two separate species in the Pacific and Caribbean is crucial.

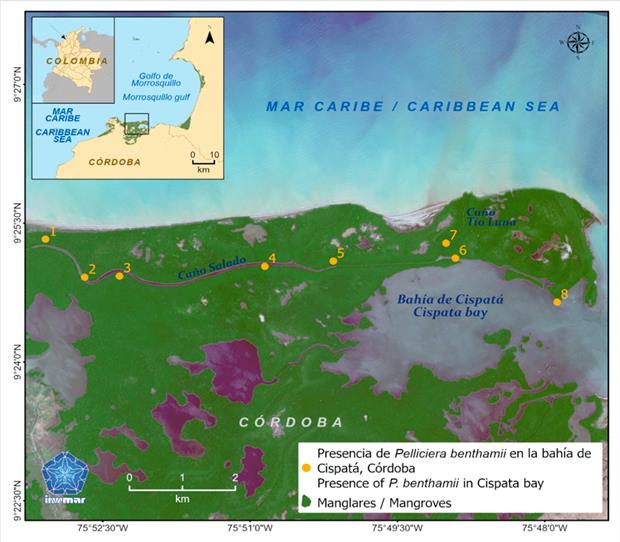

Cispatá Bay (Figure 1), located on the Caribbean continental coast of Colombia in the Cordoba department, between the municipalities of San Antero, San Bernardo del Viento, and Santa Cruz de Lorica (09°20’ - 24’ N and 75°49’30” - 54’30” W), has mangrove forests covering approximately 8,571 ha (CVS-Invemar, 2010). The average monthly temperature ranges from 26.7 to 28.6 °C (Sánchez et al., 2005), and the annual average precipitation is 1,425 mm (Sánchez et al., 2004). According to Robertson and Chaparro (1998), the delta and mouth of the Sinú River have migrated at least four times, making it one of the most dynamic areas on the Colombian Caribbean coast (Sánchez et al., 2005).

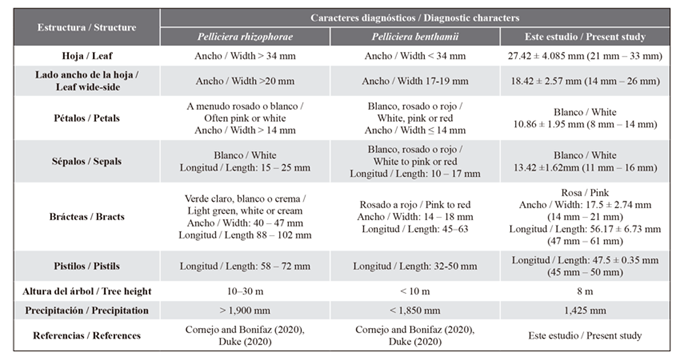

Samples of the plants were collected (Figure 2) following the protocols described by the Queensland Herbarium (2016). Measurements of width, length, shape, and leaf edge structures (glandular characteristics) were taken from the leaves. Additionally, measurements of width, length, and color were recorded for the petals, sepals, bracts, and pistils. Environmental characteristics such as precipitation (mm) and dendrometric parameters like tree diameter and height were also recorded within monitoring plots measuring 20 × 25 m (500 m2) in the study area. All data were recorded in a databases for comparison with the morphological characteristics outlined in the taxonomic keys summarized in Table 1. The botanical samples were deposited in the herbarium collection (catalog number INV TRA0007) of the Museum of Marine Natural History of Colombia (MHNMC)-Makuriwa at Invemar.

Individuals of P. benthamii are reported in association with other species in the preservation sector of Caño Salado in Cispatá Bay. The presence and permanence of P. benthamii recorded by Castillo-Cárdenas, (2015) and Duke (2020) are confirmed. These trees form a mixed mangrove forest of intermediate development, with a predominance of Rhizophora mangle L., followed by Laguncularia racemosa (L.) C. F. Gaertn and, in smaller quantities, Avicennia germinans (L.) L.

The Pelliciera benthamii trees found near the shore of Caño Salado (interstitial salinity range: 19 - 45) were characterized by having a more pronounced structural development towards the interior of the forest. The individuals located towards the end of the canal (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) (Figure 1) exhibited the most significant structural developments (DAP > 4 cm; heights > 4 m), while the trees in the sector near the mouth of Caño Salado (6, 7, and 8) displayed a lower structural development (DAP < 2.5 cm; heights < 2 m).

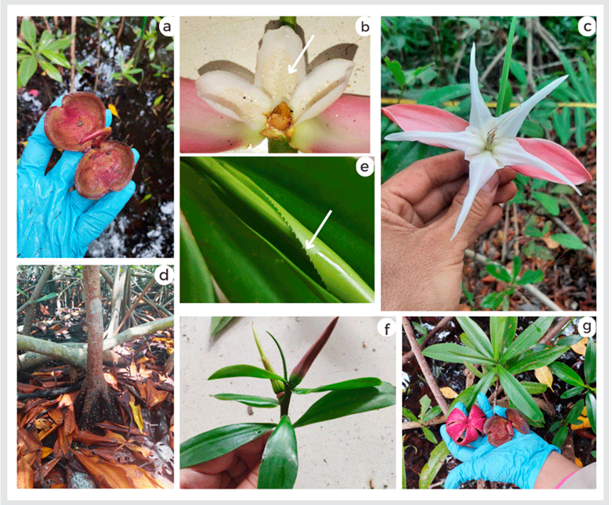

The observed individuals of Pelliciera benthamii (Figure 3) have green leaves which are subverticillate, lanceolate, simple, alternate, without stipules, asymmetric, and with a wide entire to subcrenate margin, with marginal glands (more visible in young leaves). The flowers are complete and perfect, featuring five lanceolate white petals and five white sepals with multiple nectar glands in the center, along with a solitary green bract and two reddish bracteoles on the exterior and pink on the interior (visible when they open). The stem widens at the base and grows in a pyramidal fashion. The fruit is leathery, brown, and red on the inside of the pericarp. Seedlings exhibit a pair of well-developed cotyledons before the production of leaf primordia.

Figure 3 In situ images of Pelliciera benthamii. a) Open seed with emerging plumule; b) Sepals with nectar glands; c) Open flower with 5 lanceolate petals and a pair of pink bracteoles; d) Stem with widened base in pyramid shape; e) Wide side of the leaf with marginal teeth; f) Leaves and floral bud enclosed by a pair of reddish foliaceous bracteoles; g) Leaf of a seedling, fruit pericarp, and seed. Photos: a, b, d, e, f, g-Tania Hoyos; c-Joaquín Torres.

The taxonomy of the genus Pelliciera, the oldest Caribbean mangroves, has recently been revised, resulting in a separation of two species (Cornejo and Bonifaz, 2020; Duke, 2020). Initially Pelliciera was considered a monotypic genus exclusive to the Pacific (Jiménez, 1985), but Calderón-Sáenz (1983) found it in the Caribbean in the bay of Cartagena and Barbacoas. Nowadays, with the taxonomic keys generated by Cornejo and Bonifaz (2020) and Duke (2020), there is enough evidence to support the hypothesis that there are two species, with a new one in the Caribbean: P. benthamii. In their keys, Cornejo and Bonifaz (2020) place more emphasis on the morphometry of characters such as sepals, pistil length, tree height and some environmental parameters to explain the diversification and distribution of these species (Castillo-Cárdenas, 2005); Duke (2020) provides detailed information on the leaf, including other specialized analyses not studied in this research (pollen size and texture), which validates the temporal location of the genus in the Caribbean during the Eocene (Graham and Jarzen, 1969; Fuchs, 1970; Graham, 1977). In Cispatá Bay, Sánchez-Páez (1997) reported relicts of Pelliciera rhizophorae; however, with the recently published keys it is proposed to register the species as P. benthamii as reported by Castillo-Cárdenas (2015). In the study site the taxon exhibits a restricted distribution due to anthropogenic landscape transformation. As with P. rhizophorae, particularly in the Caribbean (Polidoro et al., 2010), this anthropic disturbance makes the population highly vulnerable to extinction with low probability of recovery through recolonization of neighboring populations (Blanco-Libreros et al., 2016). Duke (2020) highlights the probable presence of P. benthamii in the Caribbean, emphasizing the importance of discovering stands in Cispatá Bay to understand the influence of geological processes, such as the emergence of the Central American Isthmus, on the differentiation of the genus Pelliciera in the Pacific and Central and South American Caribbean. Considering the above arguments, the present study recognizes the morphological and environmental characteristics of P. benthamii and its distribution in Cispatá Bay, providing information for conservation measures in the Caribbean region and contributing to the knowledge of the country’s biodiversity. However, it highlights the need for integrative taxonomy with the Caribbean and Colombian Pacific populations of Pelliciera to redefine the conservation status of both species, given the current lack of information for P. rhizophorae, which is on the IUCN Red List. To improve the status of Pelliciera spp. relicts, it is proposed to implement mangrove preservation measures in Colombia and to promote the sustainable use of natural resources in areas where Pelliciera species are present. The favorable environmental conditions for Pelliciera, identified in preservation sectors, reinforce the importance of these areas, such as in Cispatá Bay, where populations of P. benthamii were found in sectors exclusively designated for preservation (CSV-Invemar, 2010).

text in

text in