INTRODUCTION

Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens) fishing in Peru is supported by the high productivity and variability of the Humboldt current ecosystem (Nixon and Thomas, 2001; Agüero, 2007; Bakun and Weeks, 2008). Anchoveta fishing management in Peru has evolved from open access with global quotas starting in 1966 (D.S. N° 066) to a system with individual quotas per fishing units, which is denoted as the maximum permissible total catch limit (MPTCL) per vessel, established in 2008 (D.L. N° 1084) and put into effect in the first fishing season of 2009 (Aranda, 2009), thus ending an unbridled race for obtaining the highest proportion of the catch quota in the shortest possible time (dubbed as Olympic race). The MPTCL is the fishing quota assigned to each vessel in each season.

Anchoveta fishery management has a more developed regulatory framework than that of other species. It is regulated according to the purpose of the catches: direct human consumption (DHC) or indirect human consumption (IHC). The most relevant management tools are i) the general fishing law; ii) the law and regulations regarding the MPTCL, which establish differentiated systems of individual catch quotas for the industrial fleet in the north-central and southern regions; and iii) the Fisheries Management Regulation for DHC (Monteferri et al., 2020). The MPTCL represents the total quota throughout the fishing season. Moreover, anchoveta management is focused on resource sustainability, which is why global catch quotas and biological rests have been the most frequent measures.

High oceanographic variability and low forecasting capabilities generate ecological uncertainty regarding the diagnostics and management of fishery. This has caused Peruvian fishery management to be dependent on short-term environmental conditions (Bouchon, 2018) and has prompted the development of more accurate methodologies to obtain fishery-biological information thought of a scientific survey and to allow implementing very short-term management measures. This is known as adaptive management, and its purpose is to reconcile the sustainability of living resources with fishing activity, making it sustainable over time (Chávez and Messie, 2008; Arias-Screiber et al., 2011).

The application of these regulations by managers is mainly founded upon scientific evidence provided by the Peruvian Institute of the Sea (Imarpe). Imarpe’s work is fundamental to understanding the population and biological status of anchoveta. The Institute’s general mission is to promote and carry out scientific and technological research of the sea and continental waters, as well as of the living resources of both while aiming for rational utilization. They provide these studies to the Ministry of Production (Produce) in a truthful and timely manner (Produce, 2012). In addition to the biomass results of these scientific investigations, the socioeconomic factor - established by the managers - is also considered, which, in some cases, can increase or decrease the fishing quota.

The annual anchoveta catch is distributed in two fishing seasons and is carried out by purse seine fishing vessels known as bolicheras that are registered in the Produce’s Vice-Ministry of Fishery. The implementation of the system of individual quotas per vessel was a response to issues dating back to the late 90s, i.e., fleet overcapacity, overinvestment in plants and fleet, informality in the sector, the resource’s sustainability risk, and environmental issues, among others. The per-vessel individual quota is the result of distributing the MPTCL, or the total catch quota (TCQ), for IHC among a finite number of vessels, and it is the Produce who establishes, assigns, regulates, and monitors these individual quotas (Monteferri et al., 2021).

The two fishing seasons are primarily based on the periods following the spawning of the anchoveta. This species spawns almost all year long, with two higher-intensity periods, the main one being in winter (August-September) and the other one in summer (February-March) (Santander and Sandoval de Castillo, 1969; Perea et al., 2011; Bouchon, 2018). The end or suspension of the fishing season is subject to i) reaching the TCQ, ii) the extraction of the expected juveniles (even if the TCQ has not been reached), iii) the start of the spawning period, and iv) anomalous environmental conditions (e.g., the extraordinary-intensity El Niño in 1997-1998).

In recent years, the north-central region (04°30´-15°59´S) has been regarded as the one with the greatest abundance and distribution of anchoveta in comparison with the southern region (16°00´S-18°20´S) (Ñiquen et al., 2000). In these regions, two seasons are independently implemented: for the north-central region, they take place between April and June and between November and February, while, for the southern region, they take place between January and June and between July and December. This corresponds to a biannual regime.

One aspect to be considered prior to these fishing seasons is oceanographic variability. High climate variability, which may be seasonal (summer-winter), interannual (El Niño-La Niña), periodical (warm and cold periods), or secular (high and low variability, exerts an influence on the distribution and abundance of species in the pelagic and demersal ecosystems (Espino, 2014). This climate variability may generate horizontal and/or vertical displacements of anchoveta in short periods of time. This variability can also occur at the end of the research survey and the beginning of the fishing season. In interannual events such as El Niño, which affects the population of anchoveta that is partially available to the fleet given its proximity to the coast, high catch values could entail a biomass reduction if no suitable control is implemented, as occurred in the following El Niño events: 1972-73, 1982-83, and 1997-98 (Peña Tercero, 2019). The only way is to conduct periodical research to assess the impact of these events and of fishery, aiming to ensure the sustainability of the species.

One of the reasons for proposing a research question is to determine the extent of responsibility of various actors involved in decision-making aimed at maintaining a healthy anchoveta population in Peru. Considering this, the present article aims to appraise the extent of the responsibility of various actors participating in the anchoveta evaluation process, which subsequently leads to the issuance of recommendations to Produce via decision tables for determining catch quotas, primarily in the north-central region. This process begins with research conducted by Imarpe, and decisions are made by Produce independently for each zone (north-central and southern regions).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The execution of the activities corresponding to each anchoveta evaluation process is assigned to the various scientific areas of Imarpe depending on their specialty. Imarpe’s General Research Directorate for Oceanography and Climate Change (DGIOCC) is entrusted with the survey for the assessment of anchoveta spawning biomass in the north-central region (egg production method, or EPM), as well as with elaborating the final report of said operation and describing the environmental landscape and its short-term projections.

The General Research Directorate for Hydroacoustics, Remote Sensing, and Fishing Gear (DGIHSA) is entrusted with directly evaluating the biomass of anchoveta in the north-central and southern regions via hydroacoustic research surveys of pelagic resources, which are periodically carried out according to Imarpe’s field activity schedule. In addition, they must elaborate the final survey report. The General Research Directorate for Pelagic Resources (DGIRP) is entrusted with permanently coordinating the scientific aspects of field operations with the other General Directorates regarding the evaluation of anchoveta in the north-central and southern regions via indirect methods (population dynamics models) and consolidating the results of each evaluation process. In addition, they must elaborate and present the final report with fishing projections to Senior Management for their approval and submission to Produce.

The evaluation process includes all actions performed by Imarpe prior to each anchoveta fishing season (Imarpe, 2020). It comprises two phases:

Phase I. Direct methods:

Research survey for anchoveta spawning biomass

This survey allows estimating the spawning biomass of anchoveta by quantifying the eggs in the sea, a product of spawning (also known as the EPM), and it is carried out between August and September, precisely in the period of greatest reproduction or spawning of anchoveta. In these calculations, five population parameters are considered: individual average weight, partial fertility, sexual proportion, spawning frequency, and the number of eggs being produced per day.

Spawning biomass is the fraction of the stock, measured in weight, that can contribute with new specimens to the stock via the spawning process. In simple terms, spawning biomass is the result of multiplying the total biomass at a given age (or size) by the proportion of mature specimens at that age (or size). This methodology is described in Ayón et al. (2001) .

Survey for the hydroacoustic assessment of anchoveta

This survey conducts research on the distribution, biomass, and availability of the main fishing resources via hydroacoustics, i.e., by applying sound or echo in the water. The echo is emitted by a sonar system, which allows recording all objects or targets below the sea surface or water column. This system is installed on a research platform. Thanks to the intensity of the echo, the acoustic system can identify the bottom of the sea and different schools, in addition to their density. This type of survey is carried out twice a year: one in February-April (summer) and another one in September-October (spring). There are different acoustic sampling and biomass estimation techniques. The methodology employed in the Peruvian sea is described in Castillo et al. (2011) .

The oceanographic information obtained in the survey is complemented with satellite data for updating purposes. For short-term forecasts of oceanographic conditions, the outputs of international models are employed, i.e., the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts model and NOAA’s North American Multi-Model Ensemble and Coupled Forecast System models.

Phase II. Evaluation through indirect methods:

Population dynamics model

An acoustics-based model is applied, coupled with population dynamics models, wherein the anchoveta evaluation process differs from traditional ones in three aspects: i) the use of a conservative projection horizon to determine management limits; ii) the use of hydroacoustic surveys for direct observations in almost real time as an initial condition for catch projection; and iii) the inclusion of environmental variability in projections, using variable population parameters for different environmental scenarios, according to the best forecasts available regarding the state of the ecosystem. This evaluation paradigm was developed within the framework of the natural variability of the environment, mainly driven by El Niño/South Oscillation (ENSO). The procedures and implementation of this model are described in Imarpe (2020) and Oliveros-Ramos et al. (2021) . Finally, a management report on the population state of anchoveta is elaborated, which is taken to Senior Management for their approval and submission to Produce.

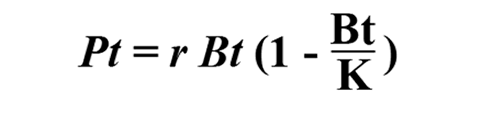

For the southern region, the Surplus Production Model is applied, which suggests that, since 2008, the fishing mortality applied to the stock, whether in terms of rate (F) or absolute figures (landings), has been below its reference level (FMSY or MSY). To estimate the maximum total catch in the southern region, the same procedure for the north-central region is followed, with a differentiating element in the dynamic biomass models. A dynamic biomass model summarizes the dynamics of a stock (growth + recruitment + mortality + migration) in a simple production function, whose formulation is:

Where: Pt is the production of the stock over time t, r is the population growth rate, Bt is the biomass of the current year, and K is the load capacity (Díaz and Oliveros, 2015).

Other complementary data

The complementary information comprises EPM surveys, oceanographic prospection, Eureka operations, and fishery monitoring, among others. This includes data on fishing biological parameters such as the selectivity of purse seine nets, growth, sexual maturity processes, spawning, and the length-weight relationship, these parameters are retrospectively estimated. In the north-central region, a diagnosis of oceanographic conditions is made for the period when the hydroacoustic survey is conducted, and this response is key (Mathisen, 1989; Bertrand et al., 2004, 2008; Joo et al., 2014; Castillo et al., 2019; Morón et al., 2019). In addition, as observed in recent years (Imarpe, 2012, 2014a, 2014b, 2015, 2016b) the occurrence of oceanographic anomalies in the distribution area altered the spatial behavior of anchoveta.

Phase III. Decision-making

Policies and Management Directorate of Produce

This office depends on the Produce’s General Directorate for Policy and Regulatory Analysis in Fishing and Aquaculture (Dgparpa). Among its main functions are formulating, evaluating, and disseminating norms, guidelines, and regulations, among others, regarding fishing and aquaculture, in addition to managing the register of vessels performing activities in the open sea, within the framework of fishery management measures.

Produce General Office of Legal Advice

It is the advisory body responsible for issuing opinions and advising on legal matters for Senior Management and the other bodies within the Ministry of Production.

METHODOLOGY

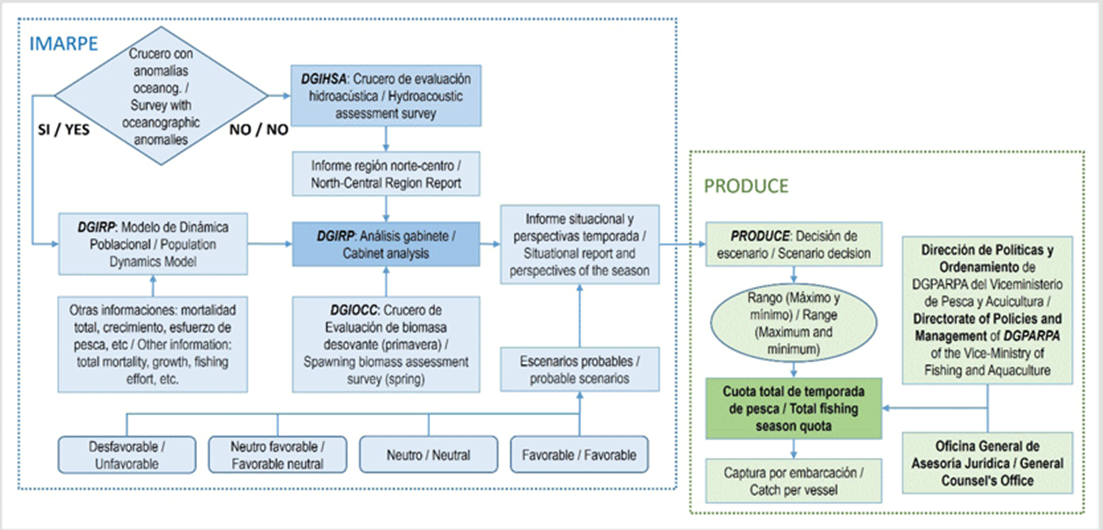

A flowchart of the process to determine the quota for a fishing season of anchoveta was elaborated (there are generally two fishing seasons in a year). This was done for both the north central and the southern regions. For decision-making regarding the total anchoveta catch quota, the situation and fishing perspectives report of anchoveta is considered for a fishing season, which is issued by Imarpe by means of their marine research. This report details the decision tables for a diversity of oceanographic and environmental scenarios, as well as the recommended environmental conditions, with exploitation rates lower than 0.35 (E ≤ 35 %). A remaining spawning biomass is considered, which would be available after the fishing season - around 5 × 106 ton (as per reports submitted to Produce). The procedures are described in Imarpe (2020) and Oliveros-Ramos et al. (2021). Produce determines the total quota for the fishing season or the MPTCL described in CSA-UPH (2011) based on the recommendations in the decision tables.

To compare the estimated biomass, the established quota, and the anchoveta catches per fishing season in the north-central region, data corresponding to the 2000-2022 period were considered. As per the quotas assigned to the fishing seasons in this region, an exploitation rate (E) lower than or equal to 0.35 was recommended in the reports related to the biological state of anchoveta and fishing forecasts.

Finally, the observation errors of the actors involved in the process of assigning the fishing quota for the north-central region were indicated. The methodology regarding these observation errors is described in Díaz et al. (in press), within the framework of an analysis of the conservation status of Peruvian anchoveta between 1950 and 2022, by means of a continuous-time stochastic surplus production model. Here, these errors are especially considered for the methodology employed in surveys for hydroacoustic survey and for studying the spawning biomass of anchoveta. This type of observation and process errors is very common in state-space models.

RESULTS

3.1 Process in each fishing season

The anchoveta evaluation process is a difficult task due to the great variability of the marine environment in different time scales, leading to sporadic and recurrent system reorganization, which impacts resources and fisheries management. For the north-central region, a diagnosis of the oceanographic conditions is carried out in the same period as the hydroacoustic survey:

i) If the conditions are stable, the data and results of the survey are used. In this case, for spring, the data of the spawning biomass survey are also considered. ii) If the conditions are unstable, i.e., there is great oceanographic variability with anomalies, the data from the previous survey are used, as well as a population dynamics model with biological information from the commercial fleet of other sources such as Imarpe coastal labs.

In both scenarios, the data from hydroacoustic surveys are provided by the DGIHSA, while assessment via indirect methods is carried out by the DGIRP, who issue a situation and fishing perspectives report for anchoveta in the current fishing season, containing decision tables with biomass values corresponding to different fishing efforts in four probable scenarios. This report is submitted to Produce, who will decide on the total quota for the fishing season. This decision is made by the Policies and Management Directorate of Dgparpa and Produce’s Vice-Minister’s Office for Fishing and Aquaculture, and it may consider an increment as social quota due to socioeconomic factors (Figure 1).

For the southern region, the surplus production model is applied, as the biomass in this region is highly variable and fluctuates around its biomass reference level, associated to the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Similarly to the procedure in the north-central region, Produce decides the season’s fishing quota.

3.2 Decision on the total anchoveta catch quota

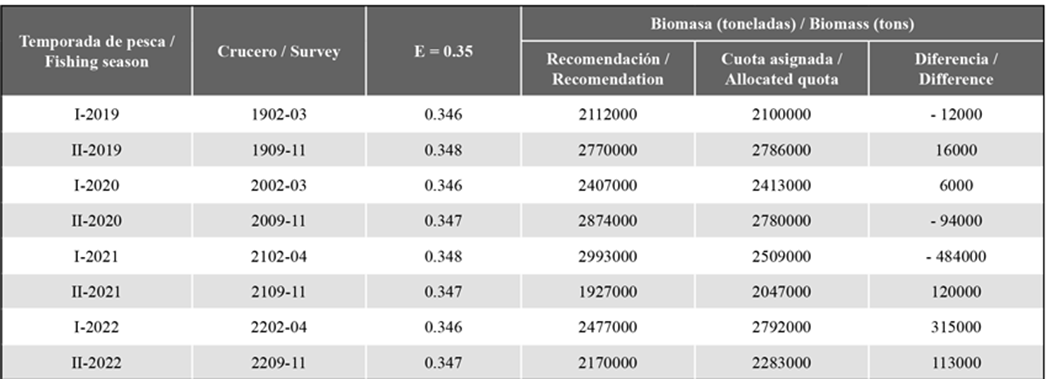

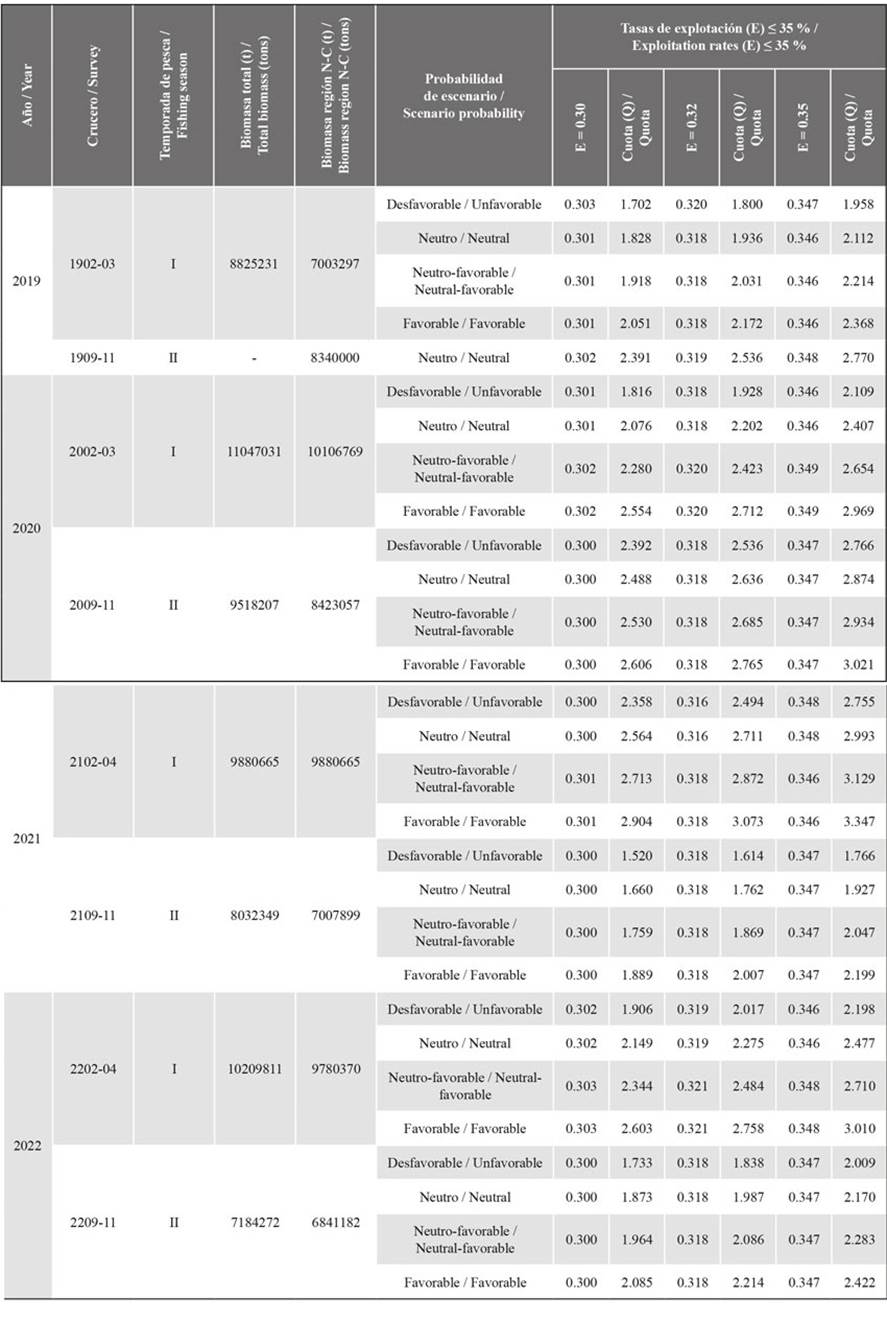

In the last four years (2019-2022), oceanographic conditions ranged from normal to mildly cold, which is why they were regarded as neutral (Table 1). In all cases, a maximum exploitation rate of 0.35 was used. However, this value could have been lower.

Table 1 Exploitation rates lower tan 35 % and quota assigned for each scenario in each anchoveta fishing season in the north-central region. The quota for E = 0.30, E = 0.32, and E = 0.35 is expressed in million tons. In the 1909-11 survey, the population dynamics model was used, and, in the 2102-04 survey, research was carried between Puerto Pizarro (03°30´S) and Bahía Independencia (14°15´S), considering that the north-central region spans from 03° 33’S to 15°59’S.

The quota (Q) is expressed in 1000 ×106 tons.

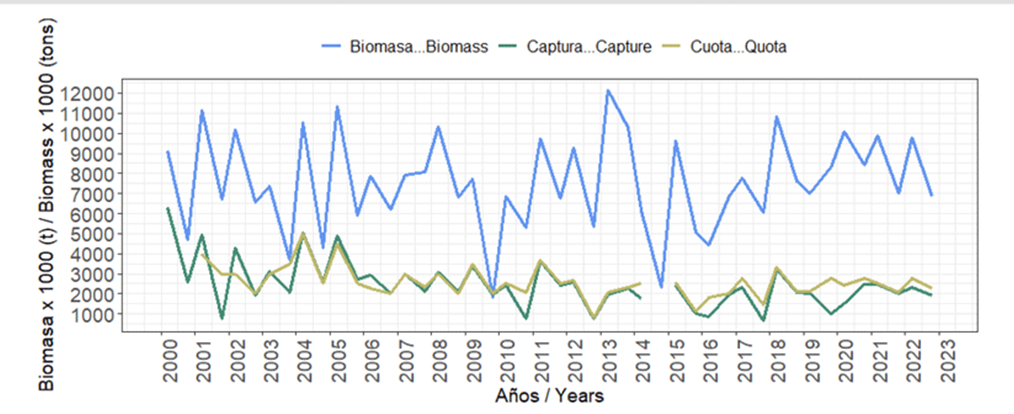

3.3 Comparison of the estimated biomass, the established quota, and the anchoveta catch per fishing season in the north-central region

The biomass estimated via the hydroacoustic methodology has been variable, with the highest values obtained in summer 2013 (1302-04 survey), i.e., 12.13 × 106 ton; and the lowest value obtained in spring 2009 (0912 survey between Salaverry and Atico), i.e., 1.80 × 106 ton. In general terms, the highest biomass values were found in summer, and, in recent years (2018-2022); they have shown a certain stability around 8.05 × 106 ton. A considerable remaining stock is observed with regard to the catch by the industrial and artisanal fleet. Anchoveta catches by the fishing fleet have shown high percentages with respect to the catch quotas between spring 2002 (fishing season II of 2002) and spring 2022 (fishing season II of 2022), except for the second fishing seasons of 2001, 2010, 2017, and 2019, with values lower than 50 %. This is fundamentally due to migrations of anchoveta (horizontal and vertical) because of the environmental variability caused by equatorial Kelvin waves.

In spring 2014 (survey 1411-12), the estimated biomass was 4.57 × 106 ton; at this time, there was no fishing season II. Moreover, there is a slightly decreasing tendency in the fishing quotas and the catches by the fishing fleet in comparison with the 2000-2006 period (Figure 2).

3.4 Analysis of the quotas assigned to the anchoveta fishing seasons between 2019 and 2022 for the north-central region

The likelihood of these years’ environmental scenario corresponded to neutral conditions. There were no significant anomalous warm events that altered the normal behavior of anchoveta. The decision tables also show exploitation rates lower than 0.35, which may be regarded by managers as a precautionary measure. Nevertheless, an increment or a social quota for the fishermen and fishing industries can be considered, as well as an economic contribution to the state.

Between 2019 and 2022, two decisions were made: i) a precautionary one in fishing season I of 2021, with a 484 × 103 ton lower biomass, in fishing season II of 2020, with a 94 × 103 ton lower biomass, and in fishing season I of 2019, with a 12 × 103 ton lower biomass; ii) a maximum one in fishing season I of 2022, with an increment of 315 × 103 ton, in fishing season II of 2021, with an increment of 113 × 103 ton, in fishing season II of 2019, with an increment of 16 × 103 ton, and in fishing season I of 2020, with an increment of 6 × 103 ton (Table 2).

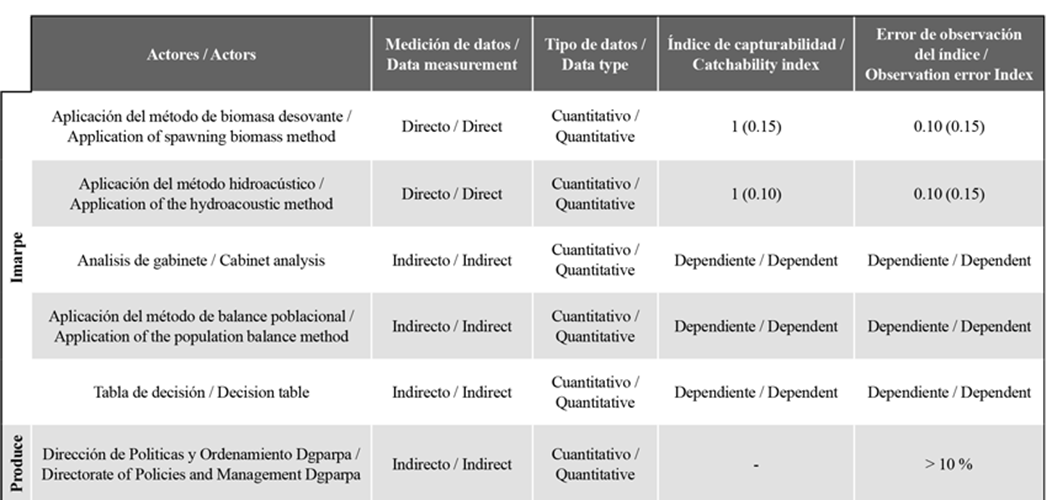

3.5 Observation errors made by the actors involved in the process of assigning fishing quotas to the north central region

In determining the MPTCL or the total permissible quota for anchoveta in fishing season II of each year for the north-central region, five actors or processes are involved, considering i) the results of the anchoveta spawning biomass survey, ii) the results of the hydroacoustic survey (in both surveys, sample measurement is direct), iii) a cabinet analysis, iv) a decision table (in the cabinet analysis, the process involving the decision tables may be considered), and v) the Policies and Management Directorate. For fishing season I, the spawning biomass surveys are not considered. As for the application of the population balance method, the data from the hydroacoustic survey are not considered, as was done for fishing season II of 2019, where data from the previous survey were used (i.e., from summer 2019).

The catchability index provided by the spawning biomass survey, as obtained via the EPM, was 0.15, with an observation error of 0.10. Meanwhile, the value reported by the hydroacoustic survey was 0.10, with an observation error of 0.10. These values are almost similar because the observation methodologies involved in the use of the acoustic equipment of both surveys are equal in the sampling designs (systematic). Something similar occurs with the confidence limits of the NASC (integration values), which oscillate between 12 and 25 %, with the lowest values reported for the summer surveys and the highest for those carried out in winter and spring.

The cabinet analysis includes uncertainty or errors in the risks recommended in the decision table. The advantage is that, during this process, the results are almost similar to those obtained in the research surveys, and the data considered in the analyses are those obtained during the research activities of Imarpe and the industrial fleet.

The result is a population balance model that starts from the previous acoustic observation (previous acoustic survey), the error in the biomass estimation is greater when the acoustic observation has greater variability due to the dispersion of the schools. Other biases or minor errors are the data from the monitoring activities carried out by fisheries and the fishing fleet. Finally, the Policies and Management Directorate also generates biases lower than 10 %, which are obtained through the increase in the quotas regarded as social and economic (Table 3).

Table 3 Biases in the actors or processes involved in determining the fishing quotas for the north-central región.

Dependent, refers to the dependence on the data used.

The anchoveta evaluation process consists of a hierarchical model, i.e., at the end of the decision table, it already contemplates all the uncertainties associated with each stage of the process. Estimating a percent error for the decision table would mean summing the whole error, from the acoustic biomass estimation to the projections made, which would represent a wide bias in the methodology for obtaining error estimates at each stage of the process.

DISCUSSION

The ministerial resolutions issued by Produce that authorize the beginning of the fishing season are aimed at the anchoveta and the white anchovy or samasa (Anchoa nasus). The abundance of the latter, as per the hydroacoustic surveys carried out by Imarpe, has been minimal. This species has been generally reported in the northern zone, in isolated areas near the coast, both in the north-central and the southern region.

The process followed to determine the MPTCL or the total permissible quota involves several groups of multi-disciplinary researchers at Imarpe, as well as administrative professionals from Produce. Over the years, this gearwork of Imarpe researchers in different areas has allowed to contribute to the sustainability of anchoveta abundance and Peru’s global recognition as the country with the best management of its fishing resources among a total of 53 countries, as per a study carried out by the University of British Columbia (Diario La República, 2009). However, this fishing regulation may be affected by anomalous warm changes that alter the marine ecosystem, causing horizontal and/or vertical migrations, as occurred in fishing season II of 2019. Castillo et al. (2021a) determined the environmental events generated by the presence of a warm Kelvin wave, in addition to biological events due to strong recruitment and vertical migration of adult specimens near the bottom.

Produce’s decision on the exploitation rate and the likelihood of the environmental scenario also requires managers with great knowledge to take sound measures. The Ministry of Production’s temporary authorities should prioritize ecosystem sustainability and the country’s economic growth. Castillo et al. (2020 and 2021b) mentioned that the abundance of anchoveta in 2019 and 2020 showed healthy conditions, with higher values in the neritic pelagic zone, and that the variability in its distribution was due to oceanographic conditions, mainly to salinity in the surface layer and oxygen at the vertical level.

Generally, Imarpe’s recommendations for fishing quotas have been based on hydroacoustic surveys since 1983, with the exception of those of fishing season II of 2019, which considered a model of population balance. The biomass results were later confirmed by Castillo et al. (2022) using diverse processing techniques for the 120 and 38 kHz frequencies. The quotas of each fishing season since 1983 have been improved over time, as there is more information available, such as electronic logs, satellite monitoring, the on-board presence of inspectors, and fishery policies framed within the concept of sustainability and the spawning period, among others. This information allows immediately issuing provisions for the temporary closure of fishing areas, avoiding a higher percentage of juvenile catches.

Another aspect to consider about the second fishing seasons, especially in recent years, is that the catch percentages are not high or are not completely reached due to cold oceanographic conditions, which have caused a wide dispersion of anchoveta, represented by schools of smaller morphometric and energy dimensions. These are not attractive for the industrial fleet’s fishing patterns. The location of a fraction of these schools in areas far from the coast (which is due to dispersion) constitutes an inconvenience in fulfilling the assigned quota.

The observation errors of the actors involved in the process of obtaining the MPTCL are greater in winter and spring, as the anchoveta population is in areas far from the coast and adequate sampling of these zones is sometimes not performed. The population’s distancing from the coast also requires a fast-sampling strategy, in order to avoid over- or underestimation due to horizontal migration. Therefore, we recommend using two or more vessels for research activities. The opposite occurs in summer, when the anchoveta population comes near the coast and sampling is adequate, reducing bias and uncertainty.

Finally, different components intervene throughout the recommendation process for determining an anchoveta fishing quota in the north-central region, showing results that are coherent with the current situation in each fishing period and that have allowed maintaining ecosystem sustainability in recent decades. Imarpe is currently undergoing an international certification process regarding its research, which will allow for greater credibility and reliability. What is indeed advisable is for fishery managers to be professionals specialized in understanding the environmental dynamics of the Humbold current system, which influences the population of anchoveta.

CONCLUSIONS

To make recommendations on the catch quota for the north-central region, the following conditions must be fulfilled: i) the use of hydroacoustic surveys, direct observation methods in almost real time, as an initial condition for catch projections; ii) the inclusion of environmental variability in the projections, using variable population parameters for different scenarios according to the best forecasts available regarding the state of the ecosystem.

To recommend a catch quota in the southern region, the surplus production model is applied in continuous time, and the decision is based on the MSY.

For the north-central region, Imarpe recommends an exploitation rate lower than or equal to 0.35, by means of a decision table for both probable oceanographic environment scenarios, considering a remaining biomass to ensure sustainability. Between 2019 and 2022, the conditions were neutral.

The fulfillment of the catch quotas in the first fishing seasons has been high (more than 90 %), whereas, in the second fishing seasons, values lower than 50 % were reported, as in 2001, 2010, 2017, and 2019.

The decision regarding the quotas for the fishing seasons between 2019 and 2022 considered two measures: a precautionary one, with a biomass lower to that in the decision table; and a maximum use, with an increase in biomass attributed to a social and economic quota (I-2022, II-2021, II-2022, II-2019, and I-2020).

In each process or stage for determining the fishing quota, there is an observation error, as in any research methodology. The highest error is observed in winter and spring because the anchoveta population distances itself from the coast, and the lowest error occurs in summer when the population comes near it.

It is recommended for fishery managers to be professionals suited to understanding the marine dynamics influencing the abundance and behavior of anchoveta.

text in

text in