INTRODUCTION

The human’s quest for their own well-being and that of others draws them to exploit different sciences and/or disciplines that lead to a knowledge of themselves and their internal and external circumstances. These link them with the way they live (Betancourt et al. 2009). The Social Determinants of Health (SDH), defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system” (OMS, 2008), are the axis to understand the causes of inequalities. From this position, the importance of the social context is evident, since human situations are articulated there; hence, communities are responsible for intervening in the definition of their needs, to become actively involved and transform (Spinelli, 2016).

In the public health framework, advancing on the SDH requires reading the living conditions based on the probability of the occurrence of the disease or vulnerability in a population ꟷa specific geographic area-, as well as a scalar look towards the micro-territories. In this respect, Molina Jaramillo (2018) states that "on the stage of local territories and in the daily places of life is where the ways of living, getting sick, and building health are specified." In this way, the relationship of the subject with the territory becomes relevant, that is, it is worth claiming the idea of territories as living spaces for the “social co-construction derived from culture” (Montes Gallego et al. 2016).

Territorial wealth is given by neighborhood relationships, the spaces and moments that are shared and developed in everyday life, perceptions, senses, skills, talents, values, popular knowledge, and abilities. Together, they constitute the community assets of the neighborhood and allow its development (Betancurth Loaiza et al. 2020).

Fernández Campos et al. (2016) assert that an asset for health is any “factor or resource that enhances the individuals’, communities’ and populations’ capacity to maintain health and well-being.” This is based on the theory of Salutogenesis, which includes, among other concepts, the Sense of Coherence and the Generalized Resistance Resources (Escobar-Castellanos et al. 2019). The first relates to the meaning of life; the second denotes those resources that help the individual overcome adversity.

On the other hand, it is the uniqueness of the communities that complicates the construction of public policies and health programs that can identify the needs and the Generalized Resistance Resources. Thus, the territories must be approached from two angles: the needs and the strengths perceived by individuals, families, and populations (Caballero Reyes & Álvarez Munder, 2021).

The customs and beliefs of these territories can be the starting point to design strategies that redirect health care focused on a biomedical model. Consequently, global actions in terms of politics and regulations that seek to overcome inequality and inequity must be directed towards understanding the different ways of life that communities traditionally have and that are generally overlooked (Franco-Giraldo, 2020).

Recent studies, such as those of Cofiño et al. (2016) and Molina-Betancur et al. (2021) have investigated asset mapping in vulnerable neighborhoods within the framework of participatory community intervention to face life challenges through the agency of collective ability.

Meanwhile, Iglesias Guerra et al. (2018) specify the need to reorient the determinants of health, "the causes of causes", to revitalize interventions in health promotion and community health, which requires reflecting on the substrate. In this case, this would be the resources, the why, what for, how, when, with what individuals, with what groups, and what efforts are made by governance and for the training of human talent.

Thus, the following questions arise: How can the perspective of health promotion be connected to that of the SHD? And how can these interactions be established? Consequently, the present document aims to establish the relationship between the SDH and community assets in a Caldas municipality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A mixed exploratory investigation was carried out with a sequential transformative design according to the classification of Hernández Sampieri et al. (2014), with two investigative stages: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative perspective provides tools to approach the interpretative richness and contextualization of a phenomenon. It is an integral process that encompasses the study of subjects' perceptions of reality within a space and a context (Cedeño-Suarez, 2001). The quantitative component brings researchers closer to the objective reality (Hernández Sampieri et al. 2014).

Population and analysis unit: For the quantitative phase, the SDH data used were taken from a process already carried out by the municipal mayors that consisted of a visit by health personnel to all the homes of Caldas. Through the completion of a document called a family file, different variables were obtained that provide information on the structural and intermediate SDH. Therefore, the studied population consisted of the total family files, duly completed and validated; there were 72 for neighborhood A and 57 for neighborhood B (information provided by the Social Observatory of the Caldas Territorial Health Directorate).

The qualitative phase involved the families of two neighborhoods in the municipality of Neira, Caldas, who voluntarily participated in the study, and with whom the assets were identified through social mapping, including collective mapping, open interviews, and participant observation.

Techniques: Analysis of the SDH described in the family files, and mapping techniques. These techniques promote participatory work by creating maps with the collective construction of the communities, where community assets with cultural, social, and emotional characteristics, among others, are reflected on paper (Fernando & Giraldo, 2016).

Instruments: The family file, containing 68 variables, was analyzed to establish the SDH of the families in the neighborhoods of interest. For the analysis of the assets, the following were considered: 31 field diaries providing information from the first to the last visit to the neighborhoods, describing their physical characteristics, and transcribing the interviews that were carried out with the different participants to build preliminary and emerging categories through the ATLAS.ti 7.0 program licensed by the University of Caldas. Additionally, an interview guide or guide to questions asked in the integration activities was used. Some of the questions included were: What is good about the place where you live? What can you do to improve life in your community? What are the characteristics or elements that stand out in the neighborhood? Furthermore, a map of the neighborhoods of the participating communities was drawn up, consisting of a sketch of the physical space of the streets and houses, as well as the economic, educational, and recreational resources of the neighborhoods. The location of the resources reflected there was corroborated with the people from the neighborhoods.

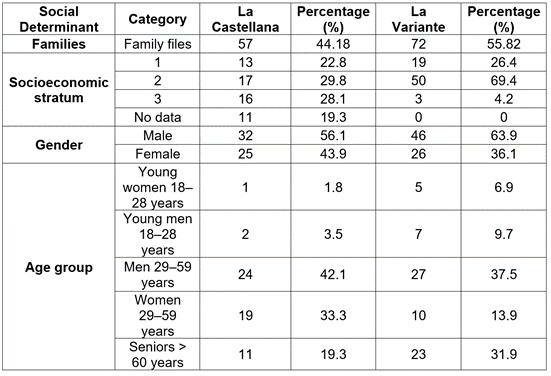

Inclusion criteria: The two neighborhoods were selected for the similarity of the family risk they presented at the time of the investigation. This risk was calculated by the Social Observatory of the Territorial Health Directorate of Caldas, which gave a score of 0 or 1 resulting from adding the 68 SDH that were either present or absent and could be seen on said platform in each family file registered in the system. The most relevant SDH can be seen in table 1 and table 2 with their respective percentages. Neighborhood A had a risk of 0.8 and B of 0.7.

Table 1 Prioritized structural determinants of neighborhoods A and B in a Caldas municipality.

Source: Compiled from data obtained from the Caldas Social Observatory.

Table 2 Prioritized intermediate determinants of the La Variante and Castellana neighborhoods in Neira.

Source: Compiled from data obtained from the Caldas Social Observatory.

Participants had to belong to the families of the two neighborhoods, they had to have been permanent residents for two years or more, be over 15 years of age, and they had to voluntarily agree, through the signing of the informed consent and assent (underage), to be involved in the activities of the qualitative phase. Those with any type of evident cognitive impairment and/or who represented a risk to the other participants, acted aggressively, or had a history of quarrels and thefts within the neighborhoods were excluded.

Procedure: Three-phase design-a descriptive phase for the analysis of the SDH registered in the family files of the studied neighborhoods, a qualitative phase using cartographic techniques, and, finally, an analytical phase that contrasted the results of the two initial phases in the two studied neighborhoods.

Methodological phases description

Phase 1. Quantitative: Preparation and contextualization: The phase began with a visit by the researchers to the two neighborhoods to explain the project to the local authorities and community leaders or people with knowledge of the neighborhoods involved where they were given information on the objective of the investigation and the wish to hold regular meetings to learn about the different characteristics of these scenarios.

Data collection: To obtain data on the families’ SDH, information was taken from the family files recorded by the Observatory of the Territorial Directorate of Health of Caldas. With the proper permits from these institutions, the platform was accessed to obtain the variables from each family file. The information was then exported to the statistical program SPSS 20.0, licensed by the University of Caldas.

Phase 2. Qualitative Fieldwork: Survey of the neighborhood and the formal and non-formal community leaders for rapprochement with the groups through neighborhood walks, which are part of the rapid participatory diagnosis technique. Descriptions of the historical, cultural, and social characteristics of these spaces, the dynamics of life, and the neighborhood relationships were obtained through meetings with members of the community, using the guide to questions. Moreover, visits were made to institutions such as the municipal hospital and the Mayor's Office (Ministry of Health and Planning), and analysis was conducted of government documents such as Neira’s Health Situation Analysis.

Visits were made once a week for 16 months in both neighborhoods. The examination of the community assets was conducted through tours of the neighborhoods, reaching out to families, community leaders, and individuals from these places, who later attended the meetings to recognize and locate the assets through mapping. Once contact was established, strategies were programmed to form a neighborhood group as the study population. This promoted an interrelation involving the social aspects of the neighborhood and, according to the number of participants, organizing and arranging collective community activities.

Phase 3. Relational: In this phase, an analysis was carried out between the SDH and the community assets to identify the possible relationships between them.

Ethical considerations: The study had the endorsement of the ethics committee of the University of Caldas and the informed consent of the participants in compliance with the parameters of the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, 2008) and Resolution 08430 of 1993 for the Colombian territory (Ministerio de Salud, 1993).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Territory recognition through the social determinants of health

In the studied neighborhoods, the most relevant social determinants were stratification, gender, and age groups, as presented in table 1. Stratification in the context of the study was between 1 (low) and 3 (medium); this data is recorded in the family files. Stratum 2 predominated in both neighborhoods A and B with 69.4 and 29.8 %, respectively. Regarding gender, the most representative was the male. In this regard, it should be noted that gender has been a social determinant within the framework of a socio-historical construction in which inequalities are generated because women suffer the consequences of a capitalist model that deepens productivity without dignifying the occupation of the organizer of a society that involves the family and social development, which deserves attention in these territories. Delgado Ballesteros (2017) asserts that the condition of the female gender has inequality to the male, which can be called "discrimination, sexism and, among others, as subordination or oppression".

Regarding age in both neighborhoods, the highest percentage was people from 29 to 59 years old. In one neighborhood, a slightly older population was observed, which reflects the heterogeneity of the micro-territories (Table 1). This dynamic is confirmed by the findings of Villegas R. (2017).

As presented in table 2, the highest percentage of schooling in both neighborhoods ranged between incomplete primary and incomplete secondary. In this regard, Arias Larroza (2016) highlights how low schooling is related to a lack of physical resources and employment opportunities that could lead to inequities. In this same sense, Díaz Torres (2017) expresses that education at the right time (childhood and adolescence) becomes a protective factor to prevent social exclusion, both in children and adults. Hence, not achieving success in the educational levels established by society, as found in the present research, limits access to decent work and participation in decision-making because autonomy and socialization are violated as mentioned by Bernal Romero et al. (2020) in a systematic review on the influence of education on young people.

The two neighborhoods studied have unemployment figures that exceed 50 % (Table 2). In the tours and home visits, large families were found living in inadequate structures with flaws in roofs and floors, among others, and whose only economic income came from one individual. In this regard, it can be affirmed that the lack of economic resources leads to the loss of autonomy and spaces to interact with other people, factors that can generate individual and collective desolation (Romero Caraballo, 2017).

In both neighborhoods, over 50 % of the population reported not working. In this respect Vélez-Álvarez et al. (2015) highlight the importance of considering how work not only provides ways to acquire economic resources for better access to housing, food, clothing, and education, among others, but also has an existential meaning for the person involved - it generates power, satisfaction, and a sense of self-fulfillment. According to Gumà et al. (2019) these consequences are closely related to determinants such as those found in the present study: the condition in which one lives at home (own home 30 %), schooling (over 60 % have minor or no studies) and health insurance status.

Knowledge of the conditions in which people live, through the SDH characterization, requires the targeting of interventions in specific areas (educational, social, economic, and political) with consequent transformations. This can only be achieved through government actions ꟷmacro-contextsꟷ to guarantee opportunities related to tracer social determinants, such as employment (Berenguer Gouarnaluses et al. 2017).

Neighborhood community assets: generalized resistance resources

Figure 1 shows that in the neighborhoods studied there were resources (human, physical, and institutional) that confirmed the understanding of health as an interaction of internal and external characteristics. Consequently, these communities developed their daily lives not only through risk, but, at the same time, from the assets specified as Generalized Resistance Resources that allow us to understand how people can overcome adversity by leading a coherent, structured, and understandable life.

Figure 1 The territory - a social construct mediated by support relationships, the leadership of older adults, spaces for coexistence and subsistence, and institutional support.

According to the results of this study, community assets are concentrated in three large groups: 1) people's resources (cultural resources and popular knowledge), 2) the physical resources of the neighborhood (structural resources of the area and economic resources) and 3) institutional resources (formal and informal associations and organizations). The emergent analysis found that these resources can be classed as one category with three subcategories, as follows (Figure 1):

The territory-a social construct mediated by support relationships, the leadership of older adults, spaces for coexistence, subsistence, and institutional support

People's resources: "Caring for others”. Some inhabitants immediately denied any positive characteristics of the neighborhood, at least in response to direct inquiry. However, when asked how they contribute to their coexistence, supportive relationships predominated. These are created through caring for others and companionship in difficult situations such as death, a deeply rooted cultural expression. The sharing of food and clothing with the neediest of the neighborhood stands out, also the sharing of talents, and prayer as a contribution to the collective well-being and the leadership of the older women.

The collective neighborhood experiences made up the starting point for strengthening the support network. In this sense, the celebration of neighborhood events keeps alive the customs of sharing and making talent visible:

1.3 NB1: "We all attend the band contest that is held every year."

This act of participating in different ways can be the means to an end (to achieve goals and objectives). Thus, participation can be understood to strengthen gregariousness and, in an emergent way, as a characteristic that is woven to demonstrate a community impact (Gatti et al. 2001) in which the people possess and develop abilities, as stated by Rivera de Ramones (2019), that allow the neighborhood to develop new ways of coexistence and even political interaction.

Older adults were recognized for their commitment, solidarity, and, particularly, their leadership. They dedicated a large part of their time to solving neighborhood problems, and, in addition, they prayed every day for the safety and health of the families in the neighborhood. The participation of this population occurred because they have lived in their own homes in this neighborhood for decades. This fortified the history and knowledge of the territory of which they are part.

The role of women and older women stands out. In the history of women in different contexts, this important work of care management is not visible, but over the year’s women have re-established the construction of political groups to meet the needs of households, as mentioned by Vega Solís et al. (2018), when analyzing the political participation of women and how they are at the forefront of collective processes such as collective kitchens, solidarity economies, and community mothers.

The neighborhood physical resources: The park, the field, the caves of the virgin, the Community Action Board (JAC) booth, shops, bars, and mechanical workshops, are configured as places of neighborhood coexistence and economic development.

Participants identified places in their neighborhood as special, considering that they provide neighborhood identity and ownership. For example, recreational and sports spaces promoted the children’s interaction, the JAC booth and the sports field were areas of participation, the prayer grottos promoted unity and were perceived as protection for the neighborhood, while the economically dynamic areas were decisive for establishing greater opportunities for coexistence and strengthening the abilities of the groups (Molina-Betancur et al. 2021).

1.8 NB2: “Places of prayer such as the Virgin grottos are embellished with flowers, candles, and photographs that allude to our faith in the Virgin Mary."

Public physical spaces make up a meeting and relationship resource, and parks, fields, grottos, and green areas also become a source to continue weaving the history of the neighborhoods, how they are appropriated, and how the population visualizes their own space to carry out health promotion actions beyond hospitals, as expressed by Berroeta et al. (2016): “Significant public spaces are those where people establish a connection between their personal life and the place; it is an interactive process that evolves over time and affects both users and spaces.”

Institutional resources: The institutions’ accompaniment demonstrated in the monitoring of sex workers, support for the elderly, activities for children, and health actions.

The institutions were internally and externally constituted to respond to social and economic needs to favor local development. In the neighborhoods, there was evidence of formal and informal organizations that promote education, social management (Families in Action) and health care (monitoring of diseases of public health concern, vaccination) in the community.

Differences were also perceived between neighborhoods: Only one had a JAC, which may be related to the availability of greater physical resources since an organized board becomes an important factor for local development as expressed by Sánchez Castañeda & Vargas Prieto (2017). So much so, that the institutional framework provides a support network for the search for solutions to problems. The strategy is to create networks with government entities, organizations, and foundations that can support the leaders and the inhabitants of the neighborhoods with economic and social capital.

Relevant to the leadership of the people who live in the neighborhoods, it was found that the JAC leader manages the police support in the neighborhood to control crime, as well as providing counseling during children's day and Christmas celebrations, traditional dates of great joy for the entire population, particularly children.

The Social Determinants of Health and community assets in the study population: The convergence of both for understanding the territory

For this analysis, the life characteristics (SDH) of the people in the study neighborhoods were crossed with the presence or absence of the assets. A table with the following characteristics was made: 35 variables extracted from the family file for each neighborhood were located on the X-axis, including housing conditions (access to public services, overcrowding, presence of vectors), socioeconomic status, access to health consultations for health promotion and disease prevention. On the Y-axis, there were 18 subcategories corresponding to the resources of the subjects, the physical, cultural and economic associations among them, power, passion, time, influence, experience, talent, care, leadership.

The presence or absence of a certain resource was assigned to each variable with a number.

The intermediate health determinants were contrasted with housing conditions, health care attendance, level of schooling, work, chronic non-communicable diseases, and lifestyle habits. The socioeconomic stratum and access to public services were correlated with money and the physical resources of the neighborhood. The economy was revitalized with physical structures and places for commerce. Those in charge of these helped to strengthen micro-enterprises, supported independent workers, and gave easy access to basic family needs.

On the other hand, it was found that the attendance at medical consultations was linked to experience and care, with older adults showing more care actions. This is possibly due to the burden of disease they have accumulated, given that they perceive that adequate health conditions provide a better quality of life. The schooling level and work were the variables associated with a greater number of community assets, so they were reflected in such resources as passion, experience, talent, abilities, knowledge and time.

Finally, health promotion and disease prevention activities are described as are lifestyle habits (smoking, consumption of alcohol and psychoactive substances, and physical exercise) and activities for the prevention of breast and cervical cancer. In these, the resources of the subjects, the neighborhood, and the associations are present or absent.

According to the SDH and assets relationship, it is necessary to identify the circumstances that allow people to face adversities and/or risks - exposure factors. One example is recreation, Romero Barquero et al. (2016) describe how recreational and integration processes can help overcome negative feelings and situations. In the studied neighborhoods, there is evidence that physical resources (economic, locational), people's resources and their interactions (passion, power, experience, care, talent, among those described in the results), and the resources of the institutions were assets that were linked to the conditions in which people live.

By making use of the internal resources they possess, resilience and self-confidence among others, people can change circumstances and begin to develop other resources that they did not know they possessed, such as leadership, love of art, and caring for themselves, as mentioned by Satorres Pérez et al. (2019) in their study of community assets to improve health in the city of Alicante.

Sánchez Marimón (2017) correlated the ten abilities with the assets, given the close influence of the talents of people with the resources they have and which they develop at the neighborhood and community levels. In summary, the SDH and community assets converge in the understanding of the territory as a social, historical, and eco-environmental space. There, undoubtedly, the macro-policies of governments are sometimes isolated from people's perceived, conceived, and lived places (Molina Jaramillo, 2018).

Consistent with the results of the present study, in other South American countries, such as Chile, (Vidal Gutierrez et al. 2014), Argentina (Bertolotto et al. 2012) and Bolivia and Brazil (García-Ramírez & Vélez-Álvarez, 2013), programs and studies have been conducted that conclude that focusing on the abilities, talents, strengths, and ancestral customs built through the close ties of the neighborhood or suburb, reduces the situations that put the health of the community at risk, in addition to enhancing the independence and autonomy of people who exercise power over their quality of life.

In this research, using the knowledge of the SDH and the identification of community assets, it was possible to better detail the communities’ ways of life. The educational level, the work, and the potential of the subjects and the neighborhood were highlighted as neighborhood and cultural values.

From the findings of this study, it can be concluded that there is a bilateral relationship between the SDH and community assets in the health-disease process. While the determinants focus on external conditions, risk, and vulnerability, depending on the disease, the assets provide a positive health perspective that strengthens the resources of people and their communities. In this sense, they complement each other reciprocally.