Introduction

This article reports a study on language teacher identities (LTI) aimed at understanding the reflexive and transformative perspectives assumed by language teachers when storying themselves as ELT professionals vis-à-vis neoliberal agendas in Colombian language policies. In this sense, the study's significance to the ELT field lies in its exploration of how teachers construct their identities through the implementation of micro-practices3 in educational settings (Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero, 2021) in connection with those from mezzo levels (i.e., workplaces, institutions, and communities) and macro levels (public policies and neoliberal discourses). Thus, the article seeks to reveal teachers’ sense of agency as they reconstruct meaningful events to depict their transformative teaching practices as a way of resisting oppressive top-down neoliberal language policies.

The first section of this article provides an overview of the theoretical foundations that underpin the study. These theoretical perspectives establish a framework for understanding how language mediates the construction of teachers’ realities and their critical identities. The following section explores the narrative inquiry approach as the chosen methodology for data collection and analysis. The most significant findings are then presented, organized into three categories of analysis: (i) between the system loopholes and oppressive practices; (ii) communities of practice as turning points to foresee critical perspectives; and (iii) future possibilities and imagined identities. These categories outline the participants' meaning-making process (Barkhuizen, 2011) as they reconstruct their life experiences in relation to their past, present, and future. Finally, the study concludes with an examination of its implications, along with suggestions for future research.

A Poststructuralist Perspective of Language Mediation in the Narrative Construction of Teachers’ Realities and Critical identities

Approaching teachers’ realities from a poststructuralist point of view entails recognizing a new role of language in understanding how meanings and identities are (re)constructed within discourse. The linguistic turn promoted by poststructuralist scholars (e.g., Bakhtin, 1981; Derrida, 1978; Foucault, 1980; Weedon, 1987) has paved the way for an increased sensitivity towards a renewed dimension of the role of language (Morgan, 2007; Norton & Morgan, 2013). Indeed, poststructuralism, more than representing a mere counter-discourse to structuralism, widens the understanding of language and foregrounds renewed perspectives on language, discourse, and identity.

For poststructuralists, language acquires a locally grounded dimension (Derrida, 1978; Weedon, 1987) that is immanent to the meanings individuals create upon discourses, the social groups they inhabit, and their lived experiences represented in stories. Therefore, in poststructuralist terms “language is central to the circulation of discourses-systems of power/knowledge that define and regulate our social institutions, disciplines, and practices” (Norton & Morgan, 2013, p. 1, italics in original). This view acknowledges the multiple realities constructed in discourse that “are always local, subjective, and in flux” (Hatch, 2002, p. 18).

When considering identity, language becomes a pivotal space for its configuration and contestation. This is because meanings are configured within language, and interpretations of oneself and others are produced through discourses (Morgan, 2007). It is important to note that the dynamics of discourse encompass more than just the dialogic process of conversation and interaction. They are also assembled in the various ways that teachers story themselves and engage in meaning-making based on their lived stories (Barkhuizen, 2015). Furthermore, events are interpreted, made tellable, and even livable upon the meanings created in stories. Therefore, in storying their lives individuals provide the substance of the lived reality (Davies, 1991). Hence, it is worth recognizing the narrative dimension of identity both constitutes and is constituted by the ways that language teachers find to shape, negotiate, and/or alter their identities.

Drawing on Bruner's (2002) perspective of narrative as a means of knowing, which is particularly useful in representing the richness of the human experience, we contend that identity is also a life story. This is because in storying their lived experiences, individuals make sense of who they are by reflecting on their past experiences and foreseeing their possibilities in the future (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). Adopting a narrative approach to understanding language teachers’ identities recognizes that identity is not static or fixed, but rather rooted in personal experiences and temporal dimensions (Elliott, 2005). In this vein, narratives are, in many ways, paths for teachers to enter the world and, through the stories narrated, they interpret and make meaning of their lived experiences (Connelly & Clandinin, 2006). Unsurprisingly, educational research has found a profound impact of the narrative turn towards understanding language teachers’ identity and its transformative dimension on teachers’ professional development (Johnson & Golombek, 2011).

A narrative approach to language teachers’ identities assumes that teachers make sense of their teaching experiences through the stories they tell (Barkhuizen, 2008). Throughout this process of storying and reflecting on past experiences, as well as contemplating possibilities for the future, teachers develop a deeper sense-making of their own identities (Quintero Polo, 2016). Nevertheless, stories are not only accounts of the past, present, or future but also, they gain their meaning from the sociocultural contexts they are intrinsically related to. Therefore, identities as life stories represent a social view of experience (Johnson & Golombek, 2002). Moreover, teachers’ identities also take place in teachers’ willingness to exert agency towards determining the sense of self (Kumaravadivelu, 2012). Accordingly, the stories teachers tell contribute to understanding who they are based on the reflection and action towards determining themselves, upon their past, present, and expected future experiences. By and large, reflection and action are essential to identity construction (Quintero Polo, 2016).

Similarly, Kramp (2004) affirms that “stories preserve our memories, prompt our reflections, connect us with our past and present, and assist us to envision our future” (p. 107). Thereby, storying lived experiences entails restructuring and re-configuring past events in the light of the present. Within such a process, storying transcends to produce a sense of temporal unity to the self (Elliot, 2005), which acknowledges the fact that stories have a particular timeframe and allows us to see the development of the self over time through the narratives individuals share. This perspective provides insights into the temporality and continuity through which teachers’ identities are constructed within their stories. Thus, a narrative constitution of the self recognizes that teachers do self in the stories they tell (Norton & Early, 2011) rather than being or having an identity, just as if it were an interior, fixed, or possessed one (Barkhuizen, 2015).

Adopting the foregoing narrative lens, we adhere to Rudolph et al. (2018) when they claim that narratives are constituted as “sociohistorically situated, negotiated and co-constructed, non-linear, conflicted and controversial, intertextual, and interpretable in numerous ways” (p. 4). This means that by narrating lived experiences, individuals engage in a discursive practice in which their identity is configured and exhibited. Narratives are not mere stories but, within a post-structuralist perspective, they are modes by which teachers make sense of who they are and display their identities.

Therefore, our perspective of narratives is grounded in the premise that “the story of one’s life is. . . a privileged but troubled narrative in the sense that it is reflexive” (Bruner, 2004, p. 693). In this train of thought, a narrative approach to the participants' life experiences allowed us to interpret them as (re)constructions of their selves (Barkhuizen, 2008) within “nets of force relations” (Bourdieu, 1995, as cited in Rincón-Villamil, 2010). In other words, this narrative choice let us look at their identities’ (re)construction as storied reflections resulting from participants’ retrospection (past), introspection (present), and prospection (future).

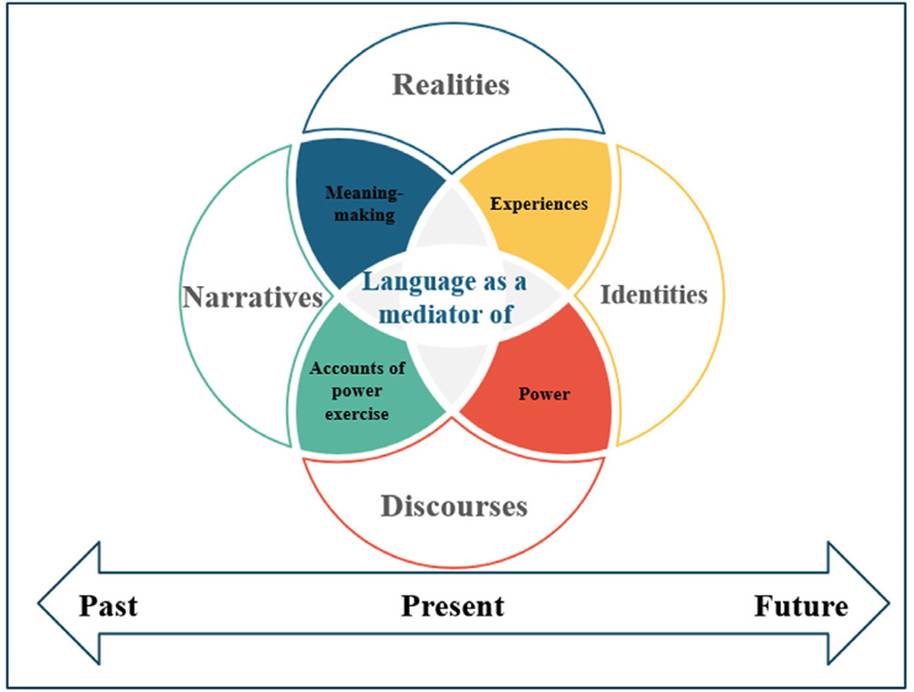

To summarize, a poststructuralist view of language highlights its role as mediator of realities, narratives, identities, and discourses. Language as a social practice becomes the avenue by which individuals materialize their identities by means of negotiation, power struggles, and experiences’ meaning-making. Thereby, identities are not solely shaped at an individual level but are also socially constructed through interactions within larger social contexts and structures. These social structures constitute and are constituted by discourses that circulate in the communities of practice individuals inhabit and ultimately endeavor to shape identities. In these dynamics, individuals make sense not only of their lived realities by the experiences lived, but also by the ways in which they story their lives. Narratives play a crucial role in assigning or negating meaning to individuals’ lived realities, leading to a process of resignifying who they were, are, and will be. This process recognizes the fluid nature of identity, which is deeply intertwined with the dynamics of storytelling and the temporality of the self (see Figure 1).

Note. Own authorship

Figure 1 The interconnected relation between realities, identities, narratives, and discourses

The foregoing discussion has also been explored in both local and international research on identity from a narrative perspective. For instance, Quintero and Guerrero (2018) studied the narratives of 80 student-teachers at the end of their undergraduate program. Utilizing analysis of narratives, the authors unveiled participants’ ongoing negotiation of the self within three perspectives: public education as a possibility, the ELT global professional, and multiple ways of being. These researchers reached the conclusion that, as a result of the program, teachers actively challenged pre-established marginalized and idealized identities that had been imposed upon them. Instead, they underwent a process of re-constructing their identities throughout the course of their academic program.

Other studies address the construction of pre-service teachers ‘identities while being part of their undergraduate program (Torres-Cepeda & Ramos-Holguín, 2019; Castañeda-Trujillo et al., 2022; Macías et al., 2020). By using a qualitative approach within the narrative inquiry, these studies found students’ interaction with academic spaces, colleagues, and teachers was core in their construction of identity as teachers. Similarly, the authors indicated that the first teaching experiences students-teachers had were destabilizing, leading to shifts in identity as teachers faced the social realities in the classroom. Moreover, Torres-Cepeda and Ramos-Holguín (2019) concluded that a post-method perspective of teaching was critical for these participants who took into agentic and critical approaches towards understanding the role of language teaching in the transformative dimension of education. Lastly, Macías et al. (2020) strongly suggest that language teacher education programs need to focus on the importance of the factors that contribute to shaping teacher identity “in order to instill an awareness of the need to develop teacher identity” (p. 9).

Methodology

This article reports a narrative study that is part of a larger study involving 13 English teachers. In this vein, our inquiry focused on two narratives considering their relevance and interweaved connection to how teachers story themselves in the construction of their realities as a result of introspection and verbalization of their past, present, or future life experiences (Quintero-Polo, 2016). These two narratives were selected not only because they constituted significant elements to answer the research question of this study: What reflexive and transformative perspectives do language teachers take on to story themselves as ELT professionals? Similarly, due to space limitations, the eleven remaining stories are presented in two other academic productions within the larger study developed by the research group ESTUPOLI. In doing so, this research aimed to reveal teachers’ sense of agency when they reconstruct meaningful events to portray their transformative and reflexive teaching practices as means of resisting oppressive top-down neoliberal language policies.

Narratives were obtained through semi-structured interviews in which both participants recounted their experiences regarding neoliberal Colombian language policies. In this sense, they took part in interviews following a two-step protocol. First, these teachers engaged in a proposed worksheet in order to elicit their reflection towards our research interest. Second, they met the researchers to converse with them about their life stories, based on the insights prompted by the worksheet questions. It is worth mentioning that the protocol was tested with another teacher and amended, especially regarding how the interviews were conducted. Additionally, participants signed a consent form, and their names were changed to ensure ethical considerations were met.

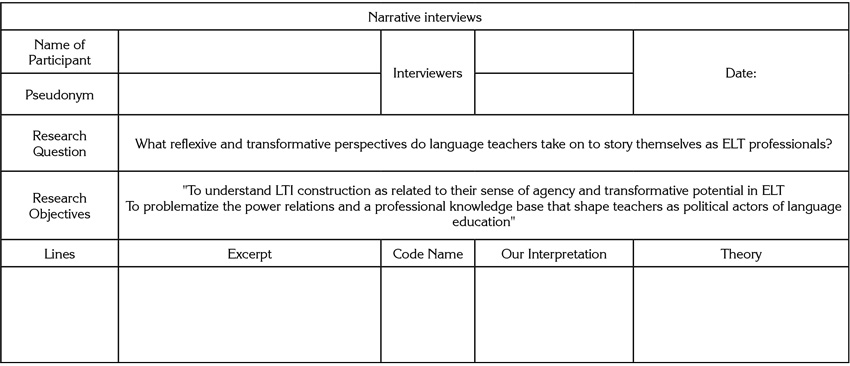

Data analysis adhered to the principles of paradigmatic reasoning (Polkinghorne, 1995). This has to do with an analysis of narratives in which the researcher engages in indexing, reducing, and categorizing data inductively (Barkhuizen et al., 2014). To begin with, both interviews were transcribed, followed by a thorough reading to identify emerging codes. These codes were then organized into an indexation matrix (see table 1).

The use of the matrix proved valuable in grounding our analysis as it facilitated the visualization of each emerging code, supported by relevant excerpts from interview transcripts. Likewise, it allowed us to record our initial interpretations of each code and later refine them, drawing upon our personal, academic, and professional experiences as well as theory and research-based literature.

Subsequently, we interpreted the participants’ stories considering significant events, people, and places associated with how they have experienced neoliberal Colombian language policies and how they imagine themselves facing them in the future. In this vein, based on Quintero Polo’s (2016) three-tiered introspective practice model (i.e., retrospection, introspection, and prospection), we weaved their stories by finding commonalities that gave rise to three categories, namely: (i) between the system loopholes and oppressive practices; (ii) communities of practice as turning points to foresee critical perspectives; and (iii) future possibilities and imagined identities.

Participants

This study endeavored to understand the reflexive and transformative perspectives two language teachers take on to story themselves as ELT professionals. In doing so, we approached their views from a narrative lens, which implies acknowledging their contexts, interests, and traits. For this reason, hereunder we introduce the participants of this study.

Pedro. Born in Florencia, Caquetá (Colombia), this language teacher has a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in English language teaching from a public university. Currently, he is pursuing his second MA in a private university and works at a public university. Throughout the years, this educator has problematized the standardization of language since, in his experiences, language standards have turned meaningless vis-a-vis his students’ needs and interests. Such a spirit has brought gratification but also tensions with other colleagues, who have underestimated his ideas for coming from a young and novice professor. Despite this, Pedro does not quit his decision to resist, his postgraduate education being the ground to pursue change.

Juan. He is from Florencia, Caquetá, and has a bachelor’s degree from a public university. By acknowledging the lack of opportunities to study in his hometown, he decided to move to Medellín and to enroll in a master’s program in foreign language teaching and learning at a public university. He has witnessed the stark contrast between his hometown and Medellín, which has made him aware of the government’s unfair distribution of resources. While thriving central cities receive ample resources, peripheral cities like his hometown are left with scarce support. Similarly, when arriving in Medellin, Juan realized the inequalities teachers experience in different sociocultural contexts in terms of instruction, discourses, and practices around language teaching and learning.

Findings and Discussion

Considering the contexts, interests, and traits of both participants, our interpretation of their stories is presented below. In doing so, we highlight the constant interplay between their retrospection, introspection, and prospection regarding their life experiences involving neoliberal Colombian language policies.

Between the System Loopholes and Oppressive Practices

This category encompasses a continuum Pedro and Juan have gone through in their professional life, namely, being targets of the educational system's oppressive practices and resisting through its loopholes. Their stories encapsulate feelings of frustration, resignation, and hurt towards top-down neoliberal practices both at the mezzo level (i.e., their workplaces) and at the macro level (i.e., the educational system). Yet, their narratives also account for critical stances regarding such practices. In this section, we interpret these practices derived from the participants’ retrospection, i.e., “introspection time after events have already taken place” (Quintero Polo, 2016, p. 110). Interpreting such a retrospective exercise also has to do with their reflection upon events, people, and circumstances that are manifested in their narratives (Bruner, 2004).

Pedro’s Story: It Has Always Been Done in That Way.

This story revolves around an argument Pedro had with a senior professor at their current workplace. This clash originated in a professors’ meeting where colleagues were discussing how to structure new syllabi for the undergraduate program courses. Deliberating about different strategies to reach an agreement, a senior professor claimed that the easiest way to construct the syllabi is relying on the contents of a textbook, which had been a tradition in the program. When narrating this episode, Pedro pinpoints that:

I feel that(a) syllabus cannot be literally based on textbook contents because when doing so we are teaching through a textbook. . . An English textbook is an aid. . . but it is not a vital resource. . . so I had an argument with them because, from their viewpoint, it is easier to follow what is pre-established and not to complicate things. . . changing or getting out of the system gives us more work (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

From the previous excerpt, we elucidate that Pedro’s story accounts for resistance to the practice of devising curriculum from prescriptive and uniform language standards that exercise veiled power (Forero-Mondragón & Quintero-Polo, 2022). This power exercise through the discourse of standard English (Forero-Mondragón, 2020) is reified in textbooks and implies consequences on the powerless end, in this case, Pedro, for instance:

I feel that in the wake of this incident and of showing myself as the one who resists, this professor somehow deems me as a revolutionary. . . like the one who wants to change everything overnight despite the fact they have worked for so many years here and (syllabi design) has always been done in that way (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

This excerpt illustrates how naturalized it is for that professor to reproduce standardized textbook contents as part of syllabi design. As a result, being challenged by an opposite perspective resulted in an offense. In addition, and more importantly, this fragment lets us see the origin of Pedro’s current position regarding his job, becoming an agent of change that transcends the instructional exercise. As presented in the next category, this agency has been consolidated thanks to his postgraduate studies since they have provided spaces and networks to rethink his professional practices.

Juan’s Story: I Had to Pay for a Standardized Test.

It is here where I (found) myself as a victim or affected by the (language proficiency) certificate because my university did not request it, so I did not hold it. . . How come I studied a five-year bachelor program in English language teaching to be told I could not work as I do not have an international certificate? Then what about my knowledge and time? (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

The foregoing extract frames the anger and disappointment Juan felt when he was asked to have a language proficiency certificate for applying for a job. His feelings were also nurtured by the fact that this participant and his family had just moved to a new city and making a living became peremptory. Therefore, even though Juan disagreed with paying for a standardized test, he did so and questioned the importance of obtaining a degree in English teaching:

Yes, I wasted time. Unfortunately, it was like that. So, what did I have to do? Man, I had to save money (and) pay (for the test. . .) I got certified (and) was hired but anyway I always asked myself ‘why study a bachelor program if I have to take an international exam?’ (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Interestingly, at a mezzo level, far from subordinating himself to imposed testing practices, this participant casts doubt on the benefits this sort of rules has on his professional identity:

(Through) a bilingual program (The new English bilingual program Colombia Very Well!), the government will affect you, closing doors to you, when they pretend to say it aims to improve” (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

At the macro level, social norms, in this case taking a test to teach English, influence behaviors, definitions, and identities of professionalism or what might be considered being a professional (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Noordegraaf & Schinkel, 2011). In this vein, while Juan does not disregard the requisite of English mastery, he sees one of its downsides:

One (has) a family and (economic) needs. . . I found it obligatory to self-train, collect some money and take an international exam (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Juan’s story accounts for conflicts between their professional and personal identities. Yet, the events and practices narrated lead to envision a critical spirit and a sense of agency toward impositions that veil an inequitable practice in the ELT field, namely, paying for language tests regularly. This is because such a practice yields economic loss for test-takers rather than an investment to access better opportunities in the job market.

This section presented Pedro’s and Juan’s meaning-making through their retrospection regarding Colombian neoliberal policies in English language education fostering discourses and practices that impose a prescriptive and top-down model of being and doing. Their narratives shed light on the loopholes these educators started to open, giving rise to micro-practices that (re)construct their identities at present, which is the core of the next category.

Communities of Practice as Turning Points to Foresee Critical Perspectives

This category comprises how the participants’ narratives depict MA programs, academic spaces, and sociocultural actors as avenues for embracing new critical perspectives. Furthermore, the narratives reveal a past-present connection between the participants’ past and present selves, as well as their renewed, evolving, and emerging perspectives on being and doing. In this vein, the purpose of this category is to represent how participants highlight, in their narratives, their postgraduate studies as a starting point to foster their criticality and reflective position upon the daily execution of their teaching profession. In addition, these narratives mirror a connection between their past and future in the light of their inclusion into academic communities. Thus, although the participants recognized the oppressive practices, they were subject to by the adoption of English language policies, now they express that they are more conscious about those policies. Plus, through their classroom micro-practices, the participants position themselves as active agents that adapt macro teaching requirements in their local spaces.

Pedro’s Story: I can teach in other ways.

In Pedro’s narrative, we identified his assumption of a master’s program as a community of practice that fosters his criticality. In this respect, he asserts:

Yeah, to me the word resist is not to be in opposition, but it is to show the possibility of doing things in another way. The National Education Ministry is not always right if I can call it like that. In this sense, my master’s program broadened my teaching perspective since I realized there are some spaces where I can teach in other ways and it made me available to position myself in the way I feel nowadays (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

According to this excerpt, Pedro assumes a critical position towards the impositions of the National Education Ministry. The participant expresses a divergent perspective by asserting that the Ministry “is not always right” and questioning its requirements. In this sense, Pedro finds his way and space (classroom micro-practices) where he can feel comfortable acting and being a teacher. The origin of this critical positioning appears as a result of studying a MA program. In this regard, this meaningful event becomes a turning point that has strengthened the participant’s critical thinking and positioning upon his doing and being. Likewise, his participation in academic communities appears as a relevant identity transition to define who he was in comparison to who he is nowadays. In this regard, Pedro expresses:

I feel I have been able to decolonize my thoughts through my experience. If I had seen this video before, I would have said ‘Such a great president, he speaks great, he is right, we need more English and we need call centers companies to come to Colombia’ because that is what my students think about English. 80% of my students work in call centers, but they do it due to their economic needs. So, if I had seen this video before, I would have surely agreed and I would have been reproducing it. But thanks to my postgraduate studies I have noticed I have started the process of decolonizing my thoughts and thus, I decolonize my students (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

Thus, reflecting upon a video that promotes the Colombian National Bilingual Plan Colombia Very Well! (Presidency of Colombia, 2014), Pedro reconstructs what could have been his position in front of this English teaching policy in comparison to what he thinks about this respect nowadays. He states that this position would have been different, and he defines that difference as a “decolonizing process”. The implication of this statement reflects a grounded critical stand where English teaching and learning acquires a political, social, and cultural role as a (de)colonizing activity. In addition, Pedro portrays himself as a reflective subject who has gained awareness of the issue “thanks to (his) postgraduate studies”. Thus, the MA program sets as a meaningful event that connects the participant’s past and present positioning.

Juan’s Story: It is An Opportunity to Open My Eyes.

Juan’s narrative aligns with Pedro's in terms of positioning. Juan also views the MA program as a turning point that results in a reflective scenario in favor of criticality construction:

The three subjects (I taught at school) that I remember had as their base the National Bilingual Plan. It was our bible. Thus, we followed it and we did what it said we were supposed to do. So, as I said, all activities, practices, everything was wonderful. We took the Guia 22 and as it says something, so we plan our lessons in agreement with it. Oddly enough, in pedagogical research, we never said it was false. That is something that I like about Universidad de Antioquia, and specifically about my master's program. And of course, the research line where I am, critical perspectives. Well, it is an opportunity for me to open my eyes (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Juan’s excerpt exposes his retrospective evaluation of past experiences, during which he did not take a critical positioning regarding the National Bilingual Plan Colombia Very Well! (NBL, Colombian Ministry of Education, 2014). In this sense, he claims that he took this policy for granted, i.e., as an unquestionable regulation that he followed just because that was the way to do it. However, due to the MA program, Juan identifies himself as a new version of a teacher with “open eyes”. Therefore, his critical identity has evolved and emerged in those moments of conflict that make him question his past in the light of the present. This past-present connection is also presented when he affirms:

There were too few moments where we wondered if this (Guía 22, Colombian Ministry of Education, 2006) was good or bad. How good, prolific, or counter-productive is it to follow all the requirements of the National Bilingual Plan and Guia 22? We asked ourselves in some moments, but did Guia 22 take into account all diversity, contexts, and needs that Colombia and its students have? (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Juan, in his newfound awareness, critically evaluates aspects that he previously overlooked. One such aspect is his current perception that the NBP is not adequately suited to local contexts. Juan manifests that he is as conscious about it and includes references to elements that are supposed to be considered when teaching and learning English such as “diversity, contexts, and students’ needs”.

All in all, the decision to pursue the master's program not only provides Juan and Pedro with a more critical vision of English language education policies, but also initiates a process of questioning that gives rise to transformative practices. These practices include their deliberate choice to make informed decisions when teaching English, taking into account local and contextualized needs. Furthermore, these emerging transformative practices do not remain static but are nurtured by the participants’ imagined future in which they foresee ways to keep and develop such perspectives as agents of change. The latter is further discussed in the following section.

Future Possibilities and Imagined Identities

This category revolves around teachers’ envisioned futures and their imagined critical identities. It delves into teachers’ transformative perspectives that are encompassed in their imagined future possibilities and practices, within their personal, academic, and professional profiles. Furthermore, we discuss how teachers’ critical identities materialize in their imagined ways of being. Thus, Pedro’s and Juan’s stories depict an imagined and desired future that exhibits their positions towards the rampant pervasiveness of neoliberalism. More interestingly, these stories mirror their ways of responding and resisting top-down models of being and becoming language teachers in Colombia.

Accordingly, both language teachers’ transformative perspectives do not remain static, but they hold a fluid nature that takes shape in an endless continuum. In other words, they envision possibilities for change in the future by gaining new understandings of their contexts, their roles, their students’ realities, the public policies influence, and more critical approaches towards language teaching studied during their master's program. These renewed understandings are neither confined to the present moment nor driven by sporadic immediacy. Instead, the participants’ envisioned futures, portrayed in their narratives, depict ways in which teachers foresee their imagined identities as active agents of change.

Teachers’ imagined identities are in many ways a representation of their beliefs, renewed worldviews, and forms of resistance. These identities are in a state of flux (Norton & Toohey, 2011; Rudolph et al. 2018) since teachers are often revisiting the new events added to their lives and configuring renewed constructions that transcend into time from who they were, who they are, and who they will be (Polkinghorne, 1995; Quintero-Polo, 2016). Pedro’s and Juan’s stories exhibit how their transformative perspectives have grown and evolved over time, extending into the future, as well as how with those transformative perspectives their imagined identities as agents of change bloom.

Pedro’s Story: I Am an Agent of Change.

Pedro’s imagined future accounts for his potential as an agent of change. By storying his past and present constructions, Pedro actively resists imposed positionalities of a society that fail to acknowledge his true self. Put it simply, Pedro’s experiences and present constructions within his postgraduate studies have made him aware that he does not need to fit in a society that does not acknowledge the possibilities and potential he has to offer. On the contrary, he contends that through small actions he can positively impact the lives of others:

I reiterate my position as an agent of change because as an agent of change I can contribute on the academic, professional, and personal. That is to say, as an academic, I feel that I can contribute a lot not only in the ELT field but also in the field of education itself so that many silenced voices or many people who are generally considered as not normal can be visualized (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

The preceding excerpt shows Pedro’s imagined identity as being negotiated and positioned from a discursive stand. Similarly, it evidences Pedro’s transformative perspectives shaped in his possible future actions. Understanding language as a way of self-representation, Pedro discursively negotiates a sense of self by assuming a position as an agent of change. As such, when embracing this position, he negotiates this sense of self with the larger social world (Norton, 2010). Within these dynamics, Pedro envisions the possibility to exert agency within his imagined identity by voicing those who have been silenced. This agentic role takes on a more critical stand when Pedro manifests that he intends to support the voices of those who are seen as non-normative in the classroom. This, in turn, portrays acts of resistance employed regardless of the restrictive, imposed, and standardizing agendas of different circulating discourses.

On the other hand, when Pedro contemplates his future self from a personal and professional profile, he understands that as an agent of change he is entitled to transform not only his context but also the lives of those around him:

On the professional side, an agent of change that really transforms not only my context, and this is linked to the personal part as well, but also all the people around me. I feel that when one is an agent of change or assumes this position, other people notice it without the need to claim “hey, I am an agent of change”, (but) because of the way you talk, the way you think, the way you act and make decisions, in terms of the smallest thing (Pedro, narrative interview, our translation).

From a discursive standpoint, we can interpret that Pedro’s imagined identity is negotiated through the mechanisms of positioning (Davies & Harré, 1990). These mechanisms act both from an inner and outer perspective. The former is illustrated when Pedro assumes his identity as an agent of change and positions himself within a specific type of being, one that, among others, transforms the varied socio-cultural milieus he inhabits and the ones of those around him. The latter is represented when he acknowledges the role that others play when they notice actions, thoughts, and decisions in the “smallest thing”. Thus, we elucidate that Pedro’s imagined positionality as an agent of change is constructed in the way others perceive and recognize him as an agent of change. Consequently, Pedro adheres to an imagined community, one in which he acts according to his identity as an agent of change and that also recognizes him as such.

Juan’s Story: Sowing Seeds.

Juan’s envisioned future portrays his possibilities to be an agent of change within his personal, academic, and professional profiles. Juan strongly believes that being and becoming an agent of change is what characterizes not only his present construction but also his future self:

That is how I see myself in the near and distant future, being an agent of change in all three areas, from the academic and professional (and personal), always looking for strategies for change in all three areas (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Based on this excerpt, we interpret that Juan’s positioning as an agent of change is his imagined future identity (Kanno & Norton, 2003; Norton 2010). This envisioned identity reflects Juan's perception of himself as someone who actively challenges conventional ways of being and doing. By positioning himself as an agent of change, we understand that he disagrees with current practices and dynamics that permeate his life. Consequently, he foresees the possibility of a change at three different levels (i.e., personal, academic, and professional).

At a personal level, Juan claimed that being an agent of change does not necessarily mean carrying out big projects. Instead, he foresees the possibility of advocating for a way of making changes through small actions. In this train of thought, he envisions himself sowing this way of seeing the world in his little three-year-old daughter:

Maybe one would think that one would make changes, I don't know, (with) a great, big project, but no, from small things, we are being agents of change. . . So, from a personal point of view, starting with my home, if my daughter is three years old, then as soon as she improves her cognitive abilities, I will also sow that way of thinking, that way of seeing life (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

Interestingly, Juan sees being an agent of change relates to small micro-practices he can do to resist preconceived ways of being and doing. Thus, despite teachers’ subjugation to particular discourses and impositions, they still account for a future where they can resist the mainstreams of circulating discourses. This is also true when teachers become aware of those circulating discourses and start to challenge them as well as to make others aware of them.

Concerning the professional field, Juan believes that he will continue carrying out practices that, as he considers, instill in his students a critical way of seeing not only the world but also the language classroom:

Even if I say it in the future, I have already started. In all the activities I do, I try to create a space where the student can question the problems of society and I will not stop doing that in the future, God’s will, but I will always try to do it. Let's ask ourselves, let's question why this is happening, what is good or what is bad that can be taken from here? and how can we think of solutions to the problems of our society? (Juan, narrative interview, our translation).

On the one hand, this excerpt illustrates how Juan’s critical inquiry is portrayed as another layer intersecting his imagined identity as an agent of change. The notion of carrying out activities that contradict a traditional language classroom and advocate for a more critical approach towards using the language with a socio-critical view reflect Juan’s resistance to imposed positionalities and his hope for a change in the future. On the other hand, this excerpt exhibits the fluid nature of identity. The excerpt illustrates renewed perspectives Juan constructs around his newly acquired knowledge, which shape the actions he takes into the real world in his teaching scenarios. Thus, the actions informed by his new perspectives reflect a way of being that has changed over time. His critical teacher self is shaped continuously, it is not a fixed entity but an ongoing construction. Unsurprisingly, in Juan’s imagined actions there are connections to present constructions, portraying his future as a continuum of his present self.

By and large, teachers’ future possibilities evidence their understanding of former experiences and present construction. Hence, teachers position themselves as agents of change whose micro-practices are geared towards a more critical stance vis-a-vis Colombian language policies. Teachers’ imagined ways of being and becoming aim at seeking change in a system that subjugates their practices and identities. This is a result of renewed views constructed around their postgraduate education and ingrained in their reflection upon their past experiences.

Conclusions

This study has shed light on some important findings concerning the reflexive and transformative perspectives of two teachers as they story themselves as ELT professionals in relation to Colombian language policies. The aim was to gain a narrative understanding of these teachers’ lived experiences and examine their interpretations of their past, present, and future constructions. In this sense, findings reveal that teachers’ transformative perspectives are initially derived from their postgraduate education as a meaningful event, which made them aware of subjugation practices and oppressive discourses they had experienced in the past. As a result of this event, they reflected upon their past, becoming aware of naturalized standardizing and homogenizing discourses that circulate in Colombian neoliberal language policies and questioning their implications.

Specifically, this study sought to reveal teachers’ sense of agency when they reconstruct meaningful events in order to portray their transformative teaching practices as means of resisting oppressive top-down neoliberal language policies. In this regard, both language teachers have devised micro-practices to resist imposed agendas and discourses in their classrooms. These micro-practices are small actions teachers implement in their daily praxis that opposes the standardized perspective embedded in language policies that permeate their teaching contexts.

Teachers’ micro-practices take a critical stand when they make the decision to enroll in a postgraduate course. These programs become communities of practice that pave the way not only for deepening their initial problematization but also for widening their scope towards more sustained approaches to resisting and opposing circulating discourses. Thus, their initial decision to enroll in a master's program becomes an act of resistance and in turn, a transformative action. By being part of an academic community, which often opens their eyes to new perspectives, teachers make more informed decisions as part of those small micro-practices in their classrooms and by doing so, they start to (re)shape their identities as ELT professionals. Furthermore, these more robust perspectives are not isolated but find a practical manifestation in teachers’ praxis at personal, professional, and academic levels. These transformative perspectives endure over time, as teachers make meaning of their past and present constructions while envisioning ways of acting and being in the future, mirroring how they are being constructed at present but also portray their imagined identities as agents of change.

This study amplified participants’ voices from their personal, professional, and academic experiences with neoliberal Colombian language policies. It also served as an avenue to stretch professional bonds among those teachers who have had similar experiences with the pervasiveness of neoliberal agendas permeating our classrooms. The latter represents an opportunity to contest uniformed and standardized views on the language, the subject, and education. In the same vein, teacher education programs can benefit from this study to propose agendas that explore from a critical lens the language policies that permeate the teaching scenarios in Colombia. We believe that the teachers’ professional options can delve into the storied realities of pre-service and in-service teachers in their daily practices to better understand the ways that neoliberalism influences the actions they take inside the classrooms. Finally, this study calls for further research with a similar scope, recognizing the value of teachers’ lived experiences in navigating Colombian policies. In this line of inquiry, future studies could employ ethnographic approaches to explore how teachers’ transformative perspectives manifest in their classrooms and influence students’ views of the world.