Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the main health-disease processes affecting the global population. Particularly, hypertension (HTN) is the most associated risk factor with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and affects approximately 46.6% of the adult population in Argentina1,2.

The food environments where people inhabit are relevant since they determine which foods residents can obtain, also restricting and guiding their choices. These environments may influence food choices towards either healthier foods or, on the contrary, towards calorie-dense foods rich in simple sugars and sodium3. Unhealthy food environments have an impact on the eating behaviors of residents and the nutrition-related diseases and NCDs that affect them, such as diabetes, obesity, and CVD4-8. Food environments include supermarkets, retail stores, fresh markets, street vendors, restaurants, and other places where people can buy and consume a variety of foods. Therefore, a food environment can be defined as a scenario where people interact with a broader food system9.

It is important to understand the characteristics of the food environment in the residential areas of individuals with non-communicable diseases (NCDs), due to its influence on consumer decision-making and its relevance in health promotion efforts. Specifically, in the management of hypertension (HTN), various consensus guidelines agree on the beneficial impact of healthy lifestyles, with diet being one of the fundamental pillars of treatment. In particular, the DASH dietary pattern (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension), developed in the 1990s in the United States as a model to reduce blood pressure, is characterized by being low in red meat, sweets, and sugary beverages, and rich in whole grains, vegetable oils, legumes, poultry, low-fat dairy products, fish, and nuts10. Additionally, the DASH pattern classifies foods according to high, moderate, or low consumption recommendations; however, adherence to these specific dietary recommendations can be challenging in an unfavorable food environment, with negative health consequences. To our knowledge, there are no studies that specifically address the characteristics of food environments according to particular guidelines, such as the DASH diet.

Based on the aforementioned background, we aimed to design and implement a geomatics methodology to explore the characteristics of the food environment in a central neighborhood of Córdoba, Argentina, focusing on the availability of food stores and shops related to cardiovascular health, in accordance with the recommendations of the DASH diet.

Materials and methods

This exploratory study is part of the project “Clinical-epidemiological approach to hypertension based on biomarkers and the food environment” (Resolution of the Secretariat of Science and Technology of the National University of Córdoba (UNC) No. 411/18) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Clinical Hospital (HNC) of UNC. In terms of its outcomes, this project not only determined the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients attending the cardiology service at the HNC (one of the most important public health centers in the city), but also evaluated the key characteristics of the Alberdi neighborhood, where this emblematic teaching hospital is located.

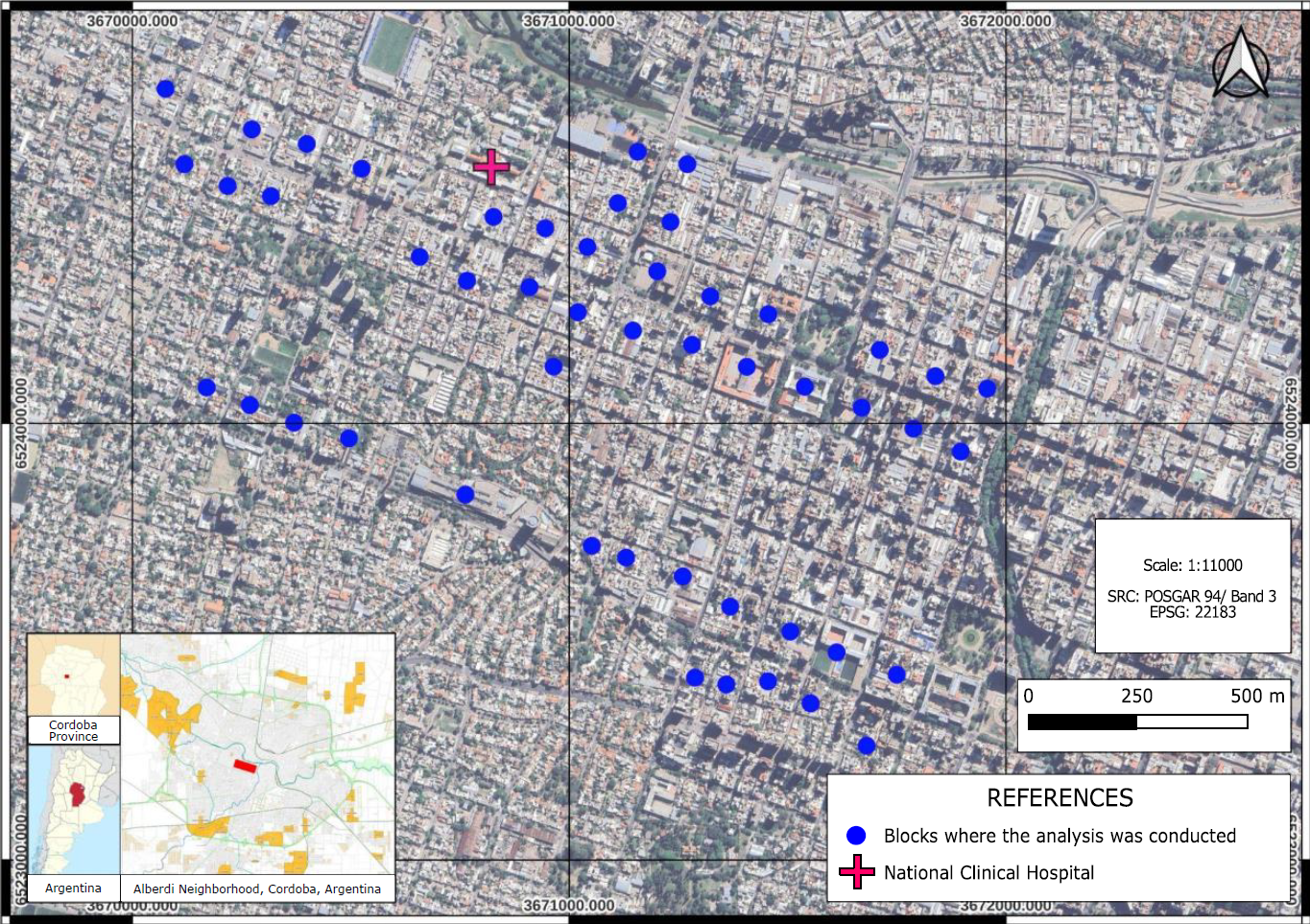

The Alberdi neighborhood, located west of downtown Córdoba, is a middle to lower-middle class residential area and one of the most important and populated neighborhoods in the city11. According to the latest national census, Alberdi covers an area of 2.45 km² and has approximately 30,000 inhabitants, accounting for 2.6% of the city's population. It is one of the most densely populated neighborhoods, with nearly 13,779 inhabitants per km², compared to the city’s average of 2,308 inhabitants per km²12,13. From a total of 179 neighborhood blocks, a representative sample was calculated, and 50 blocks were randomly selected. Subsequently, the sample was distributed considering the main streets and avenues of the neighborhood: Colón Avenue, Duarte Quirós Avenue, and Santa Fe Avenue (Figure 1).

In these selected blocks, the characteristics of urbanization and the food environment were analyzed considering two dimensions: types of businesses present and availability of foods based on the DASH diet. Authorization was requested from the owner or manager of each establishment to collect the data. The assessment of food availability was carried out using the adapted Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) model14. This instrument provided information on the commercial availability of dairy products, fruits, vegetables, canned goods, processed meats, beverages, baked goods, cereals, and miscellaneous items, among others. The focus was on the presence of the following foods related to the DASH diet intake recommendations: red group (foods recommended to be consumed in smaller amounts), yellow group (foods recommended to be consumed in moderation), and green group (foods recommended for daily consumption)10. Exploratory analyses were conducted using Stata 15 software.

The georeferencing of food businesses was based on coordinates extracted from the Google Earth platform, which allowed for the observation of the geospatial distribution of establishments using a projected coordinate system (latitude and longitude from the EPSG system: 22183 POSGAR 94/Argentina zone 3).

Businesses were classified by constructing a continuous quantitative variable that summarized information on the sales of products at each location, using the categories established in the DASH diet15, referred to as the "DASH score" by the authors. To construct this variable, it was considered that foods present in the first category of the DASH diet (green group in Table 2) subtract -1 in the DASH score formula. On the other hand, each food from the second category (yellow group in Table 2) adds 1, and finally, foods included in the last category (red group in Table 2) add 2 positive units.

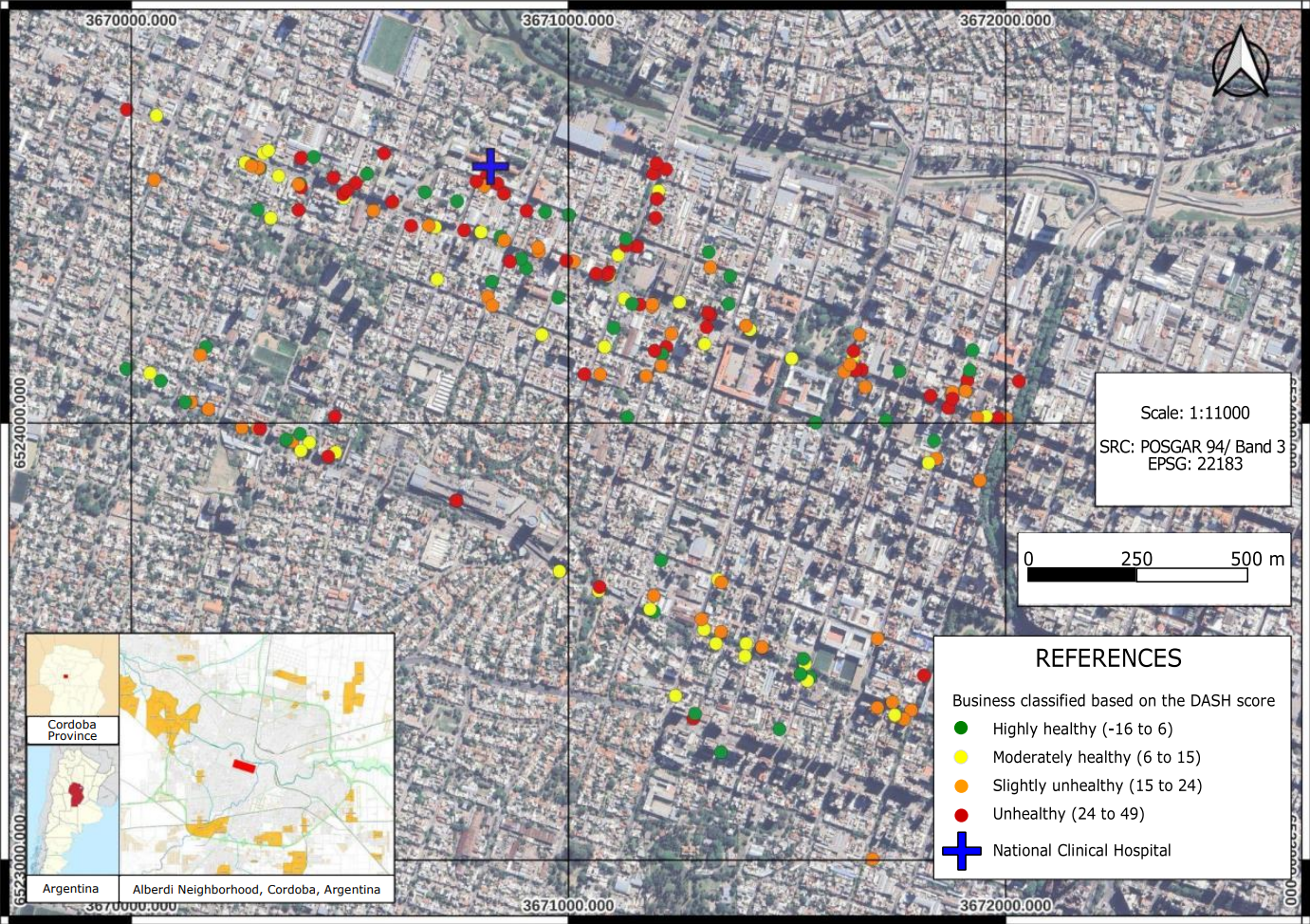

Thus, the resulting variable considers the average score to rate the business, obtaining a variable with a range of -16 to 49, which was organized into distribution quartiles (to observe greater variability in category distribution). Therefore, the first quartile of the DASH score, labeled "highly healthy," is represented in green and assumes values from -16 to 6. Similarly, the second quartile, represented in yellow, is labeled "moderately healthy" and includes values from 7 to 15. Then, the third quartile, represented in orange, is labeled "slightly unhealthy" with a range of 16 to 24. Finally, the quartile with values from 25 to 49, represented in red, was labeled "unhealthy".

Based on the final score obtained, it is interpreted that businesses with a lower score predominantly sell more foods from the green category or fewer foods from the red category, and vice versa. Thus, the result of the DASH score is naturally expressed in a color palette aligned with this logic. The thematic mapping and score construction were done using Qgis 3.22 software.

Results

Out of a total of 247 identified food establishments, 223 were surveyed, which were those whose owners agreed to participate. Table 1 shows the types of businesses surveyed.

Table 1 Distribution of food businesses in the Alberdi neighborhood, Córdoba, Argentina

a Fast food category includes pizzerias, rotisseries, bars, sandwich shops, and lomiterías (a type of meat sandwich).

A high prevalence (59.5%) of kiosks, bakeries, and fast food establishments (including rotisseries, bars, restaurants, lomiterías, and sandwich shops) was observed, followed by grocery stores and convenience shops (16.6%), which were found in at least one per block. It is also notable that only 17.4% of the businesses exclusively offered fresh foods (included in the first group of the DASH diet), such as food markets, butchers, and green groceries.

Table 2 shows the proportion of stores and their products for sale according to DASH diet guidelines. The foods with the highest availability were fresh French or mignon bread (63.7%), followed by sunflower oil (54.7%), butter (53.4%), and cold cuts and sausages (52.0%). On the contrary, the least available foods included soybean oil (0.9%), trans-fat-free margarine (2.7%), corn oil (4.5%), fresh seafood and coconut oil (4.0%), chestnuts, poppy seeds, and sunflower seeds (4.9%), and fresh river fish (7.6%). High-oleic palm oil and sunflower oil (both mentioned in the original DASH diet) were not found in the analyzed stores. Additionally, butter (53.4%) and gouda cheese (52.9%) were the most abundant in the red group, fresh French or mignon bread (63.7%) and fresh cheese (49.7%) were the most abundant in the yellow group, and sunflower oil (54.7%) and fresh vegetables (49.3%) were the most available in the green group.

Table 2 Availability of foods according to DASH diet consumption guidelines in the surveyed stores in the Alberdi neighborhood, Córdoba, Argentina

Red Group (Low consumption).

Yellow Group (Moderate consumption).

Green Group (Daily consumption).

1 Known as butter in some Latin American countries, it is an emulsion produced by churning, kneading, and washing milk fat and water.

2 A type of round cookie with a sweet filling, which may have a glazed or chocolate coating.

3 Sticks, cones, among others.

4 A type of bread with fat from Argentina.

5 A snack made from cornmeal, cheese, and salt.

6 Mix: refers to the mixture of different nuts or seeds16.

The distribution of food businesses according to the DASH score is shown in Figure 2. Based on quartiles, 25.34% of businesses were classified as "highly healthy," 25.79% as "moderately healthy," 24.89% as "slightly unhealthy," and 23.98% as "unhealthy." Businesses considered "slightly unhealthy" (last quartile) were mainly located in the north (near the HNC and along the main street, Colón Avenue), and they were more uniformly distributed compared to the other businesses. Furthermore, a higher concentration of businesses was observed in the northern part of the neighborhood compared to the south of Alberdi, Córdoba, Argentina.

Next, the categories of the score were contrasted with the types of businesses. Regarding the "highly healthy" quartile, the most frequent establishments were green groceries (almost 27%), restaurants/fast food outlets (19.6%), and health food stores (16%). As the categories changed, the types of establishments that predominated were fast food outlets (70%) and kiosks (12.2%) in the "moderately healthy" category. Additionally, fast food outlets (47.2%), grocery stores (23.6%), and bakeries (18.1%) were the most prevalent in the "slightly unhealthy" category. Finally, grocery stores (almost 40%) and fast food outlets (26.4%) dominated in the "unhealthy" category.

Discussion

Hypertension (HTN) is one of the most significant risk factors for ischemic heart disease, stroke, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), chronic kidney disease, and dementia. Increasing the availability and affordability of fresh fruits and vegetables, reducing the sodium content in packaged foods, and improving the availability of salt substitutes in the diet can help reduce blood pressure in the population17. In order to promote healthy eating habits and improve health, the Argentine Dietary Guidelines (GAPA) encourage greater consumption of fruits and vegetables of various types and colors, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, and fish, while recommending lower intake of foods high in fat, salt, and sugar18. According to these recommendations, adherence to healthy dietary guidelines, like DASH, prevents or delays the onset of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). However, other environmental factors, such as the availability of energy-dense foods, limit adherence to these nutritional guidelines. In this context, local studies have reported that most Argentinians do not follow healthy dietary recommendations, although the causes for this have not been identified1,2,19.

A healthy food environment is key to improving the diet quality of hypertensive patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to innovatively investigate the availability of foods in stores according to DASH guidelines. Considering the importance of this guide in the prevention of HTN, previous studies by our research team have reported a clinical risk profile in HTN patients attending the HNC, showing elevated blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, overweight, and high waist circumference, among other CVD risk factors20,21. Thus, studying the food environment becomes another important tool for the management and treatment of hypertensive individuals, especially in healthcare settings2,20-23.

According to Creel et al., fast food establishments provide the largest source of food outside the home. For example, in California, USA, more fast food outlets were found compared to other types of food establishments24,25. Regarding the food environment in the Alberdi neighborhood, 36.8% were restaurants, bars, sandwich shops, pizzerias, and lomiterías (sandwich shops specializing in lomito), followed by grocery stores and convenience shops. Most of these stores offer unhealthy foods, contributing to and limiting the food choices of people living and thriving in this obesogenic environment, typical of urbanized areas3. In contrast, remote rural areas are characterized by self-sustenance and limited access to food stores, which serves as a protective factor against the high consumption of unhealthy foods26.

Our results are similar to studies conducted in Leon County, Florida, USA, which analyzed the types of food stores and the demographic influence on the availability and price of healthy foods. In these studies, neighborhood income level was related to availability but not the price of some healthy foods. These authors found that supermarkets had greater availability of healthier foods, followed by convenience stores27. Another study conducted in Madrid, Spain, also found a greater availability of healthy foods in supermarkets28,29. Similarly, the study by Leone et al., mentioned earlier, highlighted that low-income neighborhoods have fewer supermarkets, a finding similar to that in our study27. In the same vein, a systematic review of quantitative and observational studies in high- and low-income countries reported that low-income areas had fewer supermarkets and fewer medium or large stores30. At this point, it is important to consider that convenience stores or neighborhood shops are characterized by a format that maximizes accessibility, minimizes costs and travel time, and offers consumers small-quantity or fractional supplies, longer operating hours, among other factors. This makes them, in our view, the most influential stores in shaping the eating habits of residents in the Alberdi neighborhood. In this regard, other studies suggest that purchase decisions are guided by the location of the establishment31.

It should be noted that in several cities in developed countries, food environments have been studied, considering “food deserts” (urban areas where it is difficult to acquire healthy, fresh, and affordable foods) and “food swamps” (areas with an abundance of high-calorie, sugar-laden, saturated fat, and salty foods and beverages), which limit healthy eating32. Although, in the present study, the distance between consumers and food stores does not mark the presence of food deserts or swamps as defined in previous studies33,34, these findings are considered an initial step in identifying such phenomena in the city of Córdoba. Additionally, several authors have suggested that the presence of food swamps is more closely associated with high rates of obesity and NCDs among residents of low-income, predominantly African American neighborhoods in the USA, implying that these areas may contribute to social disparities in diet and related health outcomes35. Conversely, another study by Liese et al. reported that purchasing food primarily from smaller stores rather than large supermarkets was associated with lower body mass index (BMI) levels36. This finding suggests that people make more rational and planned purchases despite smaller stores offering a less varied selection of healthy foods. In contrast, some studies have reported that customers of large supermarkets make less healthy purchasing decisions and have higher BMIs37-38. Thus, further research is needed that considers other variables such as food prices, shopping options, and the built environment of housing developments.

Regarding studies conducted in the region, in Brazil, Honório et al. reported that 80% of Belo Horizonte’s population lived in neighborhoods classified as either food deserts or food swamps, exposing them to unfavorable food environments for healthy eating practices39. Grilo et al. found that in the wealthier neighborhoods of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, there was a higher density of establishments selling fresh and minimally processed foods40. In Argentina, authors like Begue et al. characterized the food environments of Argentine universities, finding that 93% of businesses offered sugary soft drinks, 88% bottled water (with or without seltzer), and 86% flavored sugary water and diet sodas41. Similarly, Elorriaga et al. evaluated the relative availability and display of healthy vs. unhealthy foods in supermarkets in Buenos Aires, finding a higher availability of ultra-processed products, particularly in lower-income areas42.

On the other hand, in our study, when analyzing the availability of foods according to the DASH diet, we found a higher proportion of fresh French and mignon bread, followed by sunflower oil, butter, and cold cuts (foods in the red group). Soybean and corn oils, fresh seafood, chestnuts, poppy seeds, sunflower seeds, and fresh river fish (foods in the green group) were available in less than 8% of the establishments analyzed. These results were similar to other North American studies on the food environment of African American residents with HTN and perceptions of the DASH diet, where the availability of healthy foods (low-fat dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and lean meats) was limited in several stores and restaurants, regardless of location43. Therefore, this environment could negatively influence people’s eating behavior. It is noteworthy that Young et al. observed that the cost of DASH diet foods was higher in high socioeconomic communities; however, there is a strong trend toward lower availability in low socioeconomic communities44. Clearly, availability is not the same as cost, which was not evaluated in our study due to Argentina’s current economic scenario, with high inflation rates in recent years and annual variability in the consumer price index, making it unrepresentative as food prices differ greatly between neighborhoods and even more between nearby stores45.

In Argentina and locally, no studies were found on the influence of the food environment in relation to store types and food availability according to DASH guidelines, so the methodology proposed in this research could serve as a starting point for further exploration of the topic.

This study had some limitations, such as being a cross-sectional study, which did not allow for causality to be established. Data on purchases made by neighborhood residents in the surveyed stores were also not collected, nor were informal food sales surveyed. However, the study's strengths lie in the originality of the design, which combined spatial epidemiology tools, particularly geographic information systems, to classify food outlets according to DASH diet recommendations and visualize the local context, as the different types of stores in the neighborhood were considered.

Conclusions

Using a geospatial approach based on the guidelines of the DASH diet, this study has identified an unequal distribution of healthy foods in the Alberdi neighborhood of Córdoba, Argentina. Although the DASH diet is recognized for its potential to prevent and control hypertension, our findings suggest that the availability of its recommended foods is limited, especially those that are highly healthy and should be consumed daily according to this diet.

The predominance of kiosks and fast-food establishments, which generally offer less healthy options, may significantly contribute to dietary patterns that predispose individuals to non-communicable diseases, including hypertension. The results highlight the need for public policies that improve access to healthy foods and take into account the geographical and socioeconomic characteristics of each area to be effective. The integration of geospatial analysis and geographic information systems in this study has enabled a deeper understanding of how physical space influences the availability of healthy foods. This methodological approach underscores the importance of applying geospatial technologies to the design and implementation of more precise and effective public policies in promoting healthy food environments.

Recommendations

For future work, it would be important to continue mapping the availability of healthy foods in general (based on recommendations such as the Argentine Dietary Guidelines) and heart-healthy foods, specifically throughout the city of Córdoba. Additionally, it is essential to associate anthropometric and clinical data and include qualitative methodologies that assess urban residents’ perceptions of their local food environment. Ideally, this information should be complemented with accessibility data, specifically where neighborhood residents purchase their food, and compare the prices of healthy and unhealthy foods.