Introduction

The genus Azolla Lam. described with type A. filiculoides Lam., according to Moran (1995, 2004), is a floating aquatic fern with 1-2 mm leaves that is found in wetlands with little or no runoff, and is associated with the cyanobacteria Anabaena azollae Strasburger, 1884. According to Pereira et al. (2011), Azolla has bilobed leaves (dorsal and ventral lobes) that cover the entire rhizome. The Azolla species can be used as biofertilizer in rice culture, animal feed, and wastewater phytoremediation (Carrapiço et al., 2000; Lumpkin and Plucknett, 1980; Wagner, 1997).

Svenson (1944) made the first New World revision of Azolla species and used it as a principal character, the septate or unseptate glochidia, present in massulae (spore-masses) of microsporangia. The author recognized four species, species with unseptate glochidia are A. caroliniana Willd. and A. filiculoides. The former has small plants of 0.5-1 cm in diameter, but the latter has elongated plants 2-6 cm long. The species with septate glochidia are A. mexicana Schltdl & Cham. ex Kunze and A. microphylla Kaulf., the former with dichotomously branched plants and the later with pinnately branched plants.

Evrard and van Hove (2004) proposed a new classification for New World Azolla species with two species: A. filiculoides and A. cristata Kaulf. The authors mentioned that the former species has unicellular leaf trichomes, glochidia mainly unseptate or uniseptate, some with only a few apical septae, and its perine is warty. The latter species is characterized by bicellular leaf trichomes, glochidia mainly septate and a perine structure, quite variable, but not warty. Also, the name A. cristata for the second taxa based on the rule priority was used and not A. caroliniana.

Saunders and Fowler (1991) analyzed an Azolla section Rhizosperma and divided A. pinnata R. Br. into three subspecies, describing the subsp. asiatica R.M.K. Saunders and K. Fowler and combined subsp. africana (Desv.) R.M.K. Saunders and K. Fowler.

The phylogenetic analysis of Azolla used RAPD markers, the Jaccard similarity coefficient and UPGMA for the cluster analysis (Pereira et al., 2011), which allowed the separation of two large clades, the first contemplating the Old-World clade (Rhizosperma clade according to Svenson, 1944 and Tan et al., 1986) with Azolla nilotica Mett., A. pinnata var. imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Bonap. and A. pinnata var. pinnata. The other clade known from American taxa and is divided into two clades: one containing A. filiculoides and A. caroliniana, and the other A. microphylla and A. mexicana.

Kay and Hoyle (2001) identified Azolla pinnata, and the taxa has been listed for sale in catalogs and is found in nurseries in several of the United States. Additionally, Madeira et al. (2013) mentioned that A. pinnata is present in Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge (in the northernmost portion of the Florida Everglades) and indicated that this species is spreading rapidly, causing concern that it may displace native Azolla. Aponte (2016) suggested the movement of aquatic plants was mainly by migratory waterfowl.

In addition to the use of Azolla in aquariums mentioned by Kay and Hoyle (2001), according to Ballesteros (2011), Méndez et al. (2018), Montaño (2005) and Wagner (1997), the application of Azolla as a biofertilizer in agricultural crops provides a natural source of the crucial nutrient nitrogen, and can also be used as an animal feed, a human food, a medicine, and a water purifier. Azolla is also used in the production of hydrogen fuel, the production of biogas, the control of weeds, the control of mosquitoes, and the reduction of ammonia volatilization which accompanies the application of chemical nitrogen fertilizer. This may explain why humans have taken Azolla to different parts of the world.

On the other hand, according to Madeira et al. (2013), Azolla has an invasive potential demonstrated by various worldwide species. Quick regeneration, rapid growth, broad distribution, and dense surface mats of Azolla can obstruct weirs, locks, and water intakes impeding irrigation, boating, fishing, and recreational activities (Baars and Caffrey, 2010; Hashemloian and Azimi, 2009; McConnachie et al., 2003; Rivera, 2020). A dense surface cover may also reduce aquatic oxygen levels (Janes et al., 1996) and submerge animal populations (Gratwicke and Marshall, 2001). For this reason, it represents a problem in natral ecosystems.

Materials and Methods

Different taxa of Azolla observed in natural habitats were recollected and preserved according to the guide of Lorea and Riba (1990). The identification of species was made principally with the use of the papers published by Evrard and Hove (2004), Saunders and Fouler (1992) and Svenson (1944). The specimens collected were deposited in the herbaria: CR, MO and K, acronyms following Holmgren (1998). For morphology and reproductive structures, species were cultivated in the Natural Resources and Wildlife Laboratory (LARNAVISI). Plants were cultivated in 1.5 x 1.5 m ponds less than 0.5 m deep, enriched with chicken manure and had access to high solar radiation. Plants were cultivated in 1.5 x 1.5 m ponds less than 0.5 m deep, enriched with chicken manure and had access to high solar radiation, given ideal conditions, the plants were allowed to grow until they reached a high level of competition among themselves, inducing reproduction by spores. Subsequently, plants were studied and photographed using a microscope (Olympus LX31 and Olympus BX41 HD) and stereo microscope (Motic SMZ-168 series and Optika ST-30FX). Cameras used were those from a Samsung Galaxy note 10 and Samsung Galaxy A50 telephones.

To ensure the correct application names, original type material or digital type images were examined as available (Jstor Global Plants (http://plants.jstor.org/), and the correct use of scientific names and authors is according to the International Plant Name Index (http://www.ipni.org/ipni/plantnamesearchpage.do). The distribution of specimens was corroborated in the Tropicos Database (Missouri botanical Garden, 2016).

Results

After the morphologic and reproductive studies of Azolla specimens from Costa Rica, three species were recognized: Azolla filiculoides, A. imbricata and A. pinnata. Azolla filiculoides is the only species native to America and is characterized by dense glochidia in the massules of spores. The latter two species are new records from Costa Rica, as species scaped of cultivation and naturalized in natural ecosystems.

Redefinition of species

Azolla filiculoides Lam., Encycl. 1(1): 343. 1783.

Type. Argentina: Straits of Magellan, Commerson s.n. (P!, MPU!).

Synonyms. Azolla cristata Kaulf., Enum. Filic. 274. 1824. Type. America meridioa, Otterband s.n. (P!).

Azolla caroliniana Willd., Sp. Pl. 5(1): 541. 1810. Type. USA (Carolinas), Habitat in aquis Corolinae, Richard s.n. (B!).

Azolla mexicana Schltdl. & Cham. ex Kunze, Linnaea 18(3): 352. 1844[1845]. Type. Leibold 150 (?).

Azolla microphylla Kaulf., Enum. Filic. 273. 1824. Type. USA: "California", Chamisso s.n. (P!).

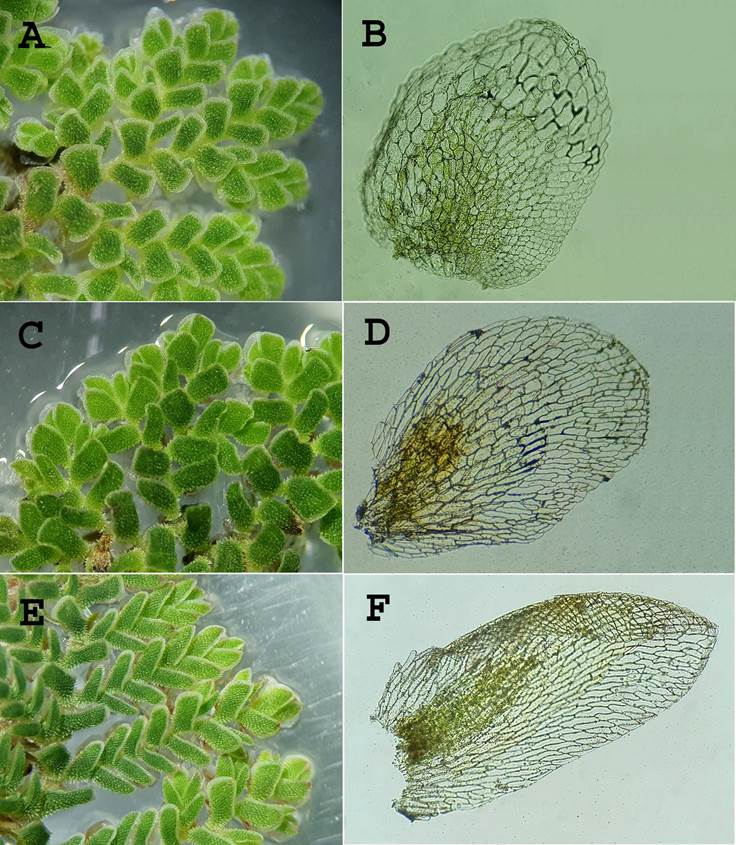

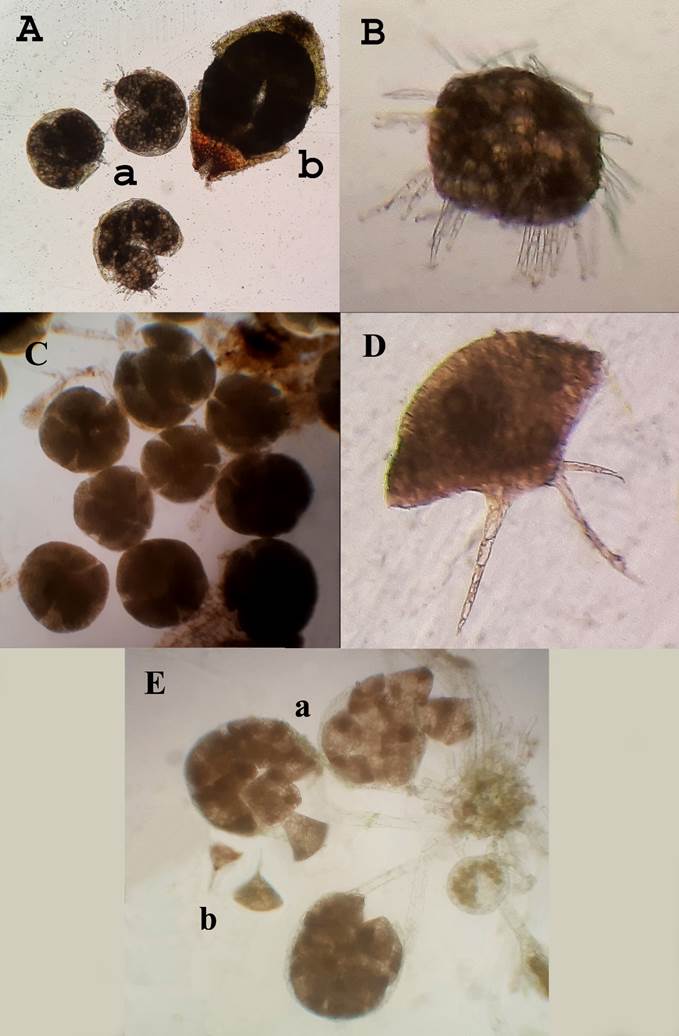

Diagnostic characters. Plants 0.5-1.5 (-2) cm long (rarely longer) in their mature state, dichotomously branched; adaxial lobes 0.7-1.2 mm long, ovate, covered with trichomes 0.1-0.2 mm long; abaxial hyaline lobes with cells quadrangular to rectangular, the cells 1.5-3 times longer than wide; massules of microspores cover by dense glochidia with blunt apex and side hooks (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

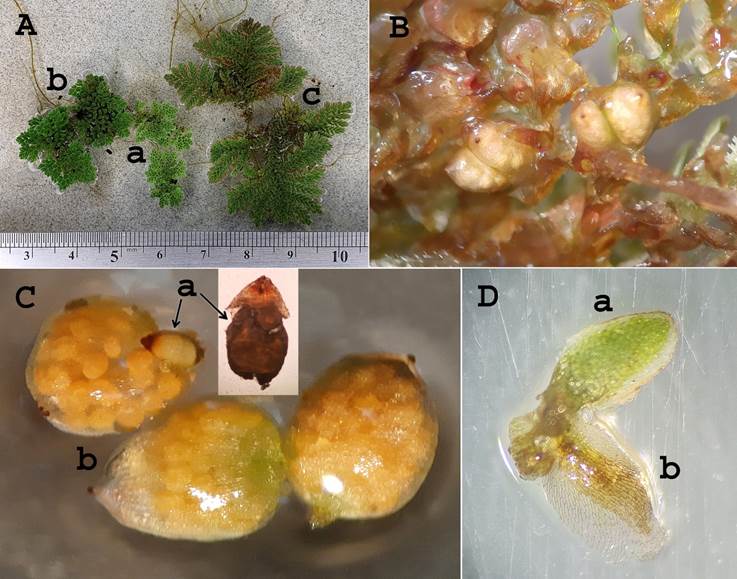

Figure 1 A. Comparative habit of the three Azolla species present in Costa Rica: a. Azolla filiculoides Lam. b. A. imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai and c. A. pinnata R. Br. B. Abaxial surface of a A. pinnata plant showing paired microsporocarps. C. A. pinnata comparative size of a. megasporocarps and b. microsporocarps. D. A. pinnata showing a. chlorophyllic adaxial lobe and b. hyaline abaxial lobe.

Figure 2 A and B. Azolla filiculoides Lam. A. Adaxial detail of plant showing chlorophyllic lobes. B. Abaxial hyaline lobe showing cells. C and D. A. imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai: C. Adaxial detail of plant showing chlorophyllic lobes. D. Abaxial hyaline lobe showing cells. E and F. A. pinnata R. Br.: E. Adaxial detail of plant showing chlorophyllic lobes. F. Abaxial hyaline lobe showing cells.

Figure 3 A and B. Azolla filiculoides Lam.: A. Microsporangia (a) and Megasporocarp (b). B. Massule with glochidia all around. C and D. A. imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai: C. Microsporangia. D. Massule with basal glochidia. E. A. pinnata R. Br.: Microsporangia (a) and Massules with one basal glochidia (b).

Taxonomic discussion. Pereira et al. (2011) obtained two clades using 13 polymorphic vegetative characters, one including Azolla filiculoides, A. microphylla and A. rubra, but it is known that the definition of A. rubra R. Br. is incorrect because all (except A. nilotica Mett.) can develop a red color in their leaves under stressful conditions. The other clade is formed by A. caroliniana and A. mexicana. However, in the cladogram derived from the analysis of 211 polymorphic RAPD markers, the result is contradictory to the previous information, because A. filiculoides forms a clade joined with A. caroliniana and the other clade is formed by A. mexicana and A. microphylla. Further, a specimen of A. caroliniana appeared mixed with A. filiculoides species, and a specimen of A. microphylla appeared mixed with A. caroliniana species. Additionally, Evrard and Van Hove (2004) mentioned that in 29 papers that they found, A. filiculoides is characterized by glochidia mainly unseptate or uniseptate, sometimes accompanied by glochidia with two or three septae, and other species are characterized mainly pluriseptate glochidia, but clearly this is not an exclusionary characteristic. Also, according to the previous information it is better to use only one species name for the American Azolla.

New records and validated name

Azolla imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai, Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 39(463): 185. 1925.

Basionym. Salvinia imbricata Roxb. ex Griff., Calcutta J. Nat. Hist. 4: 469. 1844.

Lectotype. India. Bengal: W. Rosburgh s.n. (BR!; isolectotype: BM!).

Synonym. Azolla pinnata subsp. asiatica R.M.K. Saunders and Fowler, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 109(3): 349-351. 1992. Type: Thailand. North Phayao, 2 Mar 1958, T. Sorensen, K. Larsen and B. Hansen 1829 (K).

Diagnostic characters. Plants up to 3 cm long; adaxial lobes patent to slightly imbricate; abaxial hyaline lobes shorter and wider (the relation of approx. 1.2:1, length:width), with cells principally rectangular; massules 4 (-5) per sporangia, they with three to six basal glochidia (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Known distribution. Bangladesh, Burma, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, North Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam.

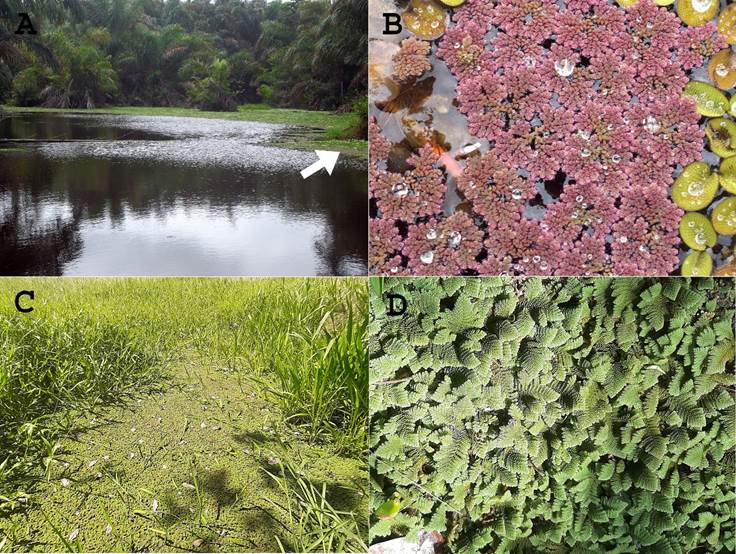

Material of new distribution. COSTA RICA. Limón: Talamanca, Sixaola, Gandoca, Lagunas 2 y 3 al S. de Gandoca, 9°35'00" N, 82°35'00" W, 0-5 m. s. n. m., 18 sep 2022, A. Rojas and M. Obando 12524 (CR, K, MO, USJ) (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4 A and B. Azolla imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai invading natural habitat in Limón, Talamanca, Sixaola, Gandoca, wetlands 2 and 3. C and D. Azolla pinnata R. Br. invading natural habitat in Puntarenas, Aguirre, between Palo Seco and Damas, Costa Rica.

Figure 5 Distribution map of Azolla imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Nakai (indicated with a pale green asterisk) and A. pinnata R. Br. (indicated with a dark green asterisk), based on our records and those mentioned in Gbif: https://www.gbif.org/es/species/ 2650106 which have been corroborated by other sources.

Taxonomic discussion. According to Pereira et al. (2011) the cladogram derived from the analysis of 211 polymorphic RAPD markers shows a first clade containing all the Old World Azolla, which is divided into two clades, one for A. nilotica, and the other one with A. pinnata. The second A. pinnata clade is divided into two clades: var. imbricata (Roxb. ex Griff.) Bonap. and var. pinnata. The above information contradicts the taxonomic classification made by Saunders and Fowler (1992), where they divided A. pinnata into three subspecies: subsp. asiatica R.M.K. Saunders and K. Fowler, subsp. africana (Desv.) R.M.K. Saunders and K. Fowler and subsp. pinnata. The previous information is combined with the morphological and reproductive characteristics that we found. The two clades mentioned by Pereira et al. (2011) are interpreted here as A. imbricata and A. pinnata.

Azolla pinnata R. Br., Prodr. 167. 1810.

Type. Australia. Hawkesbury, Richmond, R. Brown 134 (Lectotype: BM!; Isolectotypes: E, K!, MEL!). Lectotype designed by R.M.K. Saunders and K. Fowler (1992).

Synonyms. Azolla africana Desv., Mém. Soc. Linn. Paris 6(2): 178. 1827. Type: Africa. Anon. s.n. (herb. spec. P00483231) (P!).

Diagnostic characters. Plants to 6.5 cm long; adaxial lobes imbricate; abaxial hyaline lobes longer and narrower (the relation of approx. 1.7:1, length:width), with cells principally trapezoidal to rhomboidal; massules (7-) 8-10 per sporangia, with one basal glochidia (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Known distribution. Australia, Gambia, Senegal, Kenya, Tanzania, Chad, Sudan, Botswana, Madagascar, South Africa and United States of America (naturalized).

Material of new distribution. COSTA RICA. Heredia: Sarapiquí, Orquetas, asentamiento La Chaves, parcela 48, propiedad de Adita Castro, 10.383445° N, 85.948773° W, 60 m. s. n. m., 23 Jul 2010, J. González 11172 (LSCR). Puntarenas: cantón de Aguirre, carretera a Quepos, entre Palo Seco y Damas, 9°31'43" N, 84°15'52" W, 5 m. s. n. m., 14 Jul 2022, A. Rojas and M. Obando 12478 (CR, K, MO, USJ) (Figures 4 and 5).

Taxonomic discussion. See discussion under Azolla imbricata.

Key for the world species of Azolla (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

1. Plants elongate, 20-50 cm long, never red; ventral lobe of fronds more than one cell thick and chlorophyllous with stomata and trichomes; sporocarps grouped in foursA. nilotica

1'. Plants deltoid to trapezoidal, 0.5-6.5 cm long, red under adverse environmental conditions; ventral lobe of fronds of one cell thick and translucent, lacking stomata and trichomes; sporocarps grouped in twos mainly 2

2. Plants 0.5-1.5 (-2) cm long (rarely longer) in its mature state, dichotomously branched; adaxial lobes 0.7-1.2 mm long, ovate, cover with trichomes 0.1-0.2 mm long; abaxial hyaline lobes with cells quadrangular to rectangular, the cells 1.5-3 times longer than wide; massules of microspores cover by dense glochidia with blunt apex and side hooks…….A. filiculoides

2'. Plants 2-6.5 cm long in its mature state, pinnately or irregularly branched; adaxial lobes 1.3-1.7 mm long, oblong to lanceolate, cover with trichomes 0.2-0.5 mm long; abaxial hyaline lobes with cells rectangular to rhomboidal, the cells 4-10 times longer than wide; massules of microspores 1-6 basal glochidia with acute tip but without side hooks ………..3

3. Plants to 3 cm long; adaxial lobes patent to slightly imbricate; abaxial hyaline lobes shorter and wider (the relation of approx. 1.2:1, length:width), with cells principally rectangular; massules 4 (-5) per sporangia, they with three to six basal glochidia …………...A. imbricata

3'. Plants to 6.5 cm long; adaxial lobes imbricate; abaxial hyaline lobes longer and narrower (the relation of approx. 1.7:1, length:width), with cells principally trapezoidal to rhomboidal; massules (7-) 8-10 per sporangia, they with one basal glochidium ………………..A. pinnata

Discussion

According to Evrard and Van Hove (2004) the American species of Azolla can be distinguished by the septate or unseptate glochidia present in massulae of microspores, the number of cells in the trichomes present in the abaxial surface of the blade and perine of spores; all characteristics that can be observed only with electron microscopy. In this paper, two species are recorded: A. imbricata and A. pinnata, and only one species is validated from America: A. filiculoides, a key is offered for all species that uses macroscopic and microscopic characters that can be seen with a stereoscope, leaving in the background characters of reproductive structures that are not always present in plants.

The presence of alien species in natural systems is one of the main problems caused by global change (Sala, 2000). The Azolla species studied can make their incursion by various routes such as the mass transport of people and goods, aquariums or their cultivation to fertilize rice plantations; the latter two being the most likely causes of their introduction.

In countries such as Cuba, Ecuador and Bangladesh, the use of the genus Azolla as a biofertilizer has been promoted as a mechanism to alleviate the energy crisis and the high cost of chemical fertilizers (Castro et al., 2002; Montaño, 2005), as a feed supplement in aquaculture and livestock (Biplob et al., 2002; Méndez-Martínez et al., 2018), biomass production (Rivera, 2020) and in water treatment to reduce salts and heavy metals (Ballestero, 2011; Batalla and Serrano, 2016). This could have led to the introduction of species in the Neotropics, their use in cultivated areas and their incursion into natural environments.

Being that introduction to wetlands can be mainly due to the activity of birds and other animals that can act as vectors to disperse these species. The establishment of these ferns can affect native plant communities and people (Lockwood et al., 2009; Sala, 2000; Simberloff et al., 2013) because they can compete and cause local extinction and alter ecosystems.

In Spain, it is possible that the introduction of Azolla filiculoides into natural environments was caused by the movement of birds that migrate between wetlands from Portugal, where it has been established since 1920 (Sanz Elorza et al., 2004). For example, in the Doñana National Park it has been suggested that this species came from nearby wetlands, transported by birds, by contact between water masses, or translocations of birds that came from localities where this fern was introduced (Cobo, 2002). It has also been reported in Segovia (Spain) that the migration of waterfowl combined with the sexual and asexual reproduction of Azolla has facilitated their expansion in natural environments (Martín, 2010). This same behavior may be what favored the naturalization of this genus in Costa Rica.

For their part, mammals have played a clear role in the dispersal of seeds, spores, and even complete individuals of ecosystems, because they consumed it and later excreted it, or it adhered to their hair and was thus transported, in addition to the ability to move between different ecosystems including wetlands (Mora Cabeza et al., 2015). Therefore, it is possible that species of this group also facilitate dispersal in natural environments. Added to the observation, carried out in our cultivation ponds of transport carried out by raccoons (Procyon lotor), domestic rats (Rattus norvegicus f. domestica and Rattus rattus) and house mice (Mus musculus).

Given its importance in various economic activities and its capacity for dispersion through various means, it is essential to propose management measures to reduce the risk of invasion, especially in protected wild areas according to the IUCN (2019).