Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile vol.14 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2012

The Impact of Regional Differences on Elementary School Teachers'

Attitudes Towards Their Students' Use of Code Switching

in a South Texas School District

El impacto de las diferencias regionales en las actitudes de docentes de primaria

respecto a la alternancia de códigos por parte de los estudiantes

en un distrito escolar del sur de Texas

Guadalupe Nancy Nava Gómez

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, México

nancynava77@yahoo.com.mx

Hilda García

Texas A&M University-Kingsville, USA

kuhig000@tamuk.edu

This article was received on April 12, 2011, and accepted on November 20, 2011.

This study focused on investigating whether the teachers' geographical distribution influences their attitudes towards their students' use of code switching. The study was guided by the following research question: Are there differences between teachers' opinions of the north elementary schools and teachers' opinions of the south elementary schools, which are predominantly Hispanic, towards their students' use of code switching? If so, why? A twenty-item structured survey was utilized. The population consisted of 279 elementary school teachers at seven Northern and seven Southern schools in the same South Texas region. The data were analyzed with descriptive statistics. Findings showed that Southern teachers had more prejudices towards code switching than those from the North, who were more receptive to this socio-cultural and linguistic phenomenon due to the ethnic makeup of their classrooms.

Key words: Code-mixing, code switching, language maintenance, language shift, transitional programs.

En esta investigación se buscó indagar si la ubicación geográfica de los maestros de primaria influía en su percepción acerca de la alternancia de códigos de los estudiantes de un distrito escolar del sur de Texas. La pregunta central fue: ¿Existe alguna diferencia entre la opinión de los maestros de escuela primaria del sur y aquellos maestros del norte, quienes son principalmente hispanos, en cuanto al uso de la alternancia de códigos de sus alumnos? En caso afirmativo, ¿por qué? Se usó un instrumento de 20 reactivos. La población estudiada fueron 279 maestros de 7 escuelas primarias del norte y 7 del sur de la misma región. Se usó un método de estadística descriptiva para analizar los datos. Los resultados muestran que los maestros del sur tienen más prejuicios acerca de la alternancia de códigos que los del norte. Estos últimos se caracterizan por ser más receptivos a este fenómeno sociocultural y lingüístico debido a la conformación de sus aulas de clase.

Palabras clave: alternancia de códigos, cambio lingüístico, mantenimiento de la lengua, mezcla de códigos, programas de transición.

Introduction

Even though we might think we speak

a standard form of a particular language, we most

likely speak a variation of the same instead

(Yule, 2006, p. 195).

Code switching has usually been referred to as the use of more than one language in the course of a single communicative episode. The study of code switching has attracted a great deal of attention over the past two decades, most likely because it defies a strong expectation that only one language will be used at any given time (Fishman, 1991). In addition, Yule (2006) states that "going beyond stereotypes, those involved in serious investigation of regional dialects have devoted a lot of survey research to the identification of consistent features of speech found in one geographical area compared to another" (p. 196). These dialectal studies consist of drawing dialect boundaries or isoglosses in order to identify certain linguistic features pertaining to one particular speech community.

For this reason, this particular study focused on the analysis of geographical data pertaining to elementary school teachers' opinions and beliefs about their students' use of code switching in the same geographical region. The aim is to identify the differences that exist between the Northern and Southern elementary school teachers' opinions in regard to the use of code switching in their classrooms, and the impact of these perceptions and beliefs on their students' academic achievement.

Review of the Selected Literature

Throughout the years, code switching has been approached from two main angles in linguistic research. First, as part of the formal linguistics agenda, in which this phenomenon has been identified as the result of a series of linguistic and grammatical constraints. For example, Gumperz (1997) stated that code switching is used when speakers build on the contrast between two grammatical systems to convey substantive information, in equivalent situations, that cannot be conveyed by the grammatical devices of a single system.

Code switching has also been studied as a social marker through which people identify themselves among other speakers of different languages. For example, Gal (1988) pointed out that "code switching is a conversational strategy used to establish, cross or destroy group boundaries; to create, evoke or change interpersonal relations with their rights and obligations" (p. 247).

According to Chaika (1994) "sometimes a foreign language phrase will [be] thrown out to see if a stranger really belongs or is 'one of us'" (p. 336). Mexican-Americans living along the South Texas border region, for example, frequently employ words or entire phrases in Spanish unconsciously, for example phrases such as: "I took my car to the service, y me dijeron que there was nothing wrong with it" (I took my car to the service, and I was told there was nothing wrong with it), or "¿Me vas a ayudar con mi homework?" (Are your going to help me with my homework?). It is believed that throwing around words or phrases as shown in these examples "may be a sign of proficiency in either the L1 or L2, resulting in commanding only few words or phrases" (pp. 336-337). In addition, Bright (1997) stated that:

it would never be possible to capture unconscious language change 'in the act' simply because its operations required too long a period of time. In this view, trying to observe language change is like trying to observe the motion of a clock's hands: One cannot see the change, but if we look again later, we perceive that change has occurred. (p. 83)

Bright (1997) also goes on to mention that "once a change is initiated by a single individual (for whatever reason), its subsequent spread through a language community occurs when, and to the extent that, it is imitated by other speakers" (p. 85). In contrast, Albert and Obler (1978) point out that the second language is learned either like the first, at home or from peers (as in the case of children's immigrant parents who make an effort to speak the new language (English) but have an accent, as a product of their mother tongue's influence; however, children eventually learn the unaccented speech from their peers), or in the academic setting (p. 7). Students have been able to imitate this language change by switching between codes (English and Spanish) in different settings such as the classroom, at home, and/or with peers. Moreover, when there is a linguistic contact situation in which one language is recognized as the dominant language and the other is exclusively confined to informal (or restricted) uses such as family and friends, social conflicts and linguistic tensions emerge as a result. Code switching, related to the use of Spanish and English along the South Texas border region, for instance, has been associated with the following aspects:

a) Speaking disadvantages,

b) Cognitive deficiencies,

c) Lack of linguistic ability,

d) Lack of intelligence,

e) Low academic performance,

f) Lack of prior knowledge and command of mother or target language, and

g) Use of language by a low social class or uneducated people. (Nava, 2009)

However, a new line of research about the use of code switching suggests that this linguistic phenomenon has to be analyzed and examined as a third or new mother tongue resulted from the contact between two languages within the same region or geographical location (Chaika, 1994). Code switching may be taken to represent a creole language, a product of the combination of two linguistic codes (Yule, 2006). As pointed out by Baker (2000), "from a linguistic and grammatical point of view, such stable code switching should not be analyzed in terms of donor or recipient language, but on its own terms as a third linguistic code or language" (p. 33).

But, how can we describe the entailment between attitudes and teaching? The word attitude (from Latin aptus) is defined within the framework of social psychology; attitudes are clearly described as a subjective or mental preparation for action. Bilingual teachers develop a visible posture toward specific linguistic happenings in the classroom such as code switching. Baker (2006) discusses the main characteristics of attitudes as follows:

- Attitudes are cognitive and affective.

- Attitudes are dimensional rather than bipolar. They vary in degree of favorability and unfavorability.

- Attitudes predispose a person to act, but the relationship between attitudes and actions is not a strong one.

- Attitudes are learned, not inherited or genetically based.

- Attitudes tend to persist but they can be modified by experience.

Generally speaking, attitudes are seen as men

tal predispositions which could determine human behavior. Changes in attitudes towards students belonging to a bilingual community or minority group are only possible if there is teacher awareness of the importance of students' linguistic background.This paper reviews how geographical factors may influence teachers' attitudes towards their students' use of code switching, and relates this to the makeup of their classrooms.

Statement of the Problem

Even though some elementary school teachers, who work with a highly predominant Hispanic community, identified themselves as certified bilinguals, they do not believe that students should code switch in their classrooms. There are some studies (Garza & Nava, 2005, 2007; Nava & Garza, 2007; Nava, 2009) indicating that elementary school teachers (who work with a highly bilingual community) consider that code switching should not be allowed in schools because it represents a detriment or disadvantage for bilingual students. Moreover, research findings show that elementary teachers consider code switching to be the result of a lack of proficiency and a major cause of academic failure for those students whose mother tongue is one other than English.

Method

Data Collection Procedures

A twenty-item structured survey was designed to ask open and close-ended questions. The items were designed taking into consideration the insight of Garza and Nava, 2005, 2007; Nava and Garza, 2007; Nava, 2009. The geographical data section included grade level, years of experience, Bilingual/ ESL certification, dominant language, proficiency in the dominant language, and the classroom's ethnic composition. This in turn contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the negative attitudes observed in teachers working in the southern schools compared to those teachers working in the northern schools; however, both groups of teachers belong to the same South Texas geographical region.

Data Analysis Procedures

Descriptive statistics were utilized in analyzing the twenty-item survey. A quantitative type of research was carried out in order to review and report the results. SPSS (Software Package for Social Studies) was utilized as well. The twenty items were studied separately; they were categorized and analyzed from three different perspectives: cognitive, social, and teachers' attitudes towards code switching. The items were analyzed in terms of the percentages of average usage in the narrative to present the results. The average scores were then compared on an item-by-item basis. This was done in order to facilitate and contrast the results obtained from the Northern schools participants' responses and those obtained from the Southern schools participants' responses. In this paper, the results from previous studies are included in order to compare the findings in this part of the study with previous ones and obtain a comprehensive overview of the elementary school teachers' attitudes and beliefs towards their students' use of code switching by analyzing the geographical data.

Selection of Participants

The survey was sent off by mail to the principals of each school and answered by 279 teachers from both Northern and Southern elementary schools of the same South Texas geographical region. The elementary school teachers answering from the North totaled 129, while the participants from the South totaled 150. Candidates had to meet the following criteria: (a) be a part of the same geographical region; (b) be certified elementary school teachers; and (c) have at least one year of teaching experience.

Previous Research Findings

Previous studies (Garza & Nava, 2005, 2007; Nava & Garza, 2007; Nava, 2009) explored the cognitive aspects, social attitudes, and teachers' attitudes and beliefs towards their students' use of code switching in their classrooms. The following is a general overview of the previous research findings:

Cognitive Perspective

Garza and Nava (2005) reported that code switching represented a cognitive advantage. For example, it was found that automaticity in the switching of linguistic codes resulted from the different internal mechanisms that children use for a wide variety of purposes (p. 108). In addition, they suggested that automaticity was the result of the control obtained after internalizing both linguistic patterns. They also concluded that the use of code switching reflected the label of automaticity that bilingual children have achieved in both languages.

Overall, the results showed that teachers tried to eliminate code switching in their classrooms. As a result, the participant teachers used some strategies such as redirecting to the standardized language (English-only). As a final note, researchers in this study suggested that code switching could be considered as a communicative strategy resulting in cognitive flexibility that bilingual children may use for linguistic exchange rather than a deviant form of communication (Garza & Nava, 2005).

Social Perspective

In this paper (Garza & Nava, 2007), code switching was defined as the alternation between two languages. The participants in the study (N= 279) reported code switching in their everyday social activities. In addition, all participants believed that code switching should be accepted in schools; however, they reported not to allow it in their own classrooms. The majority admitted that they switch codes among friends and family, especially in relaxed and familiar settings. They reported that code switching is acquired at home, and that students switch codes more between first and third grades of schooling than in fourth and fifth grades. The participants responded that students switch codes with family and friends mainly and are able to communicate effectively with peers. Therefore, code switching was restricted to informal uses or contexts rather than formal ones such as the academic settings (Garza & Nava, 2007; Nava & Garza, 2007). Researchers also concluded that participants in the study considered that code switching should only be part of the bilingual students' informal linguistic repertoire rather than a communicative strategy elementary students employed at school for academic purposes since it may result in poor academic achievement.

In a nutshell, in this study it was found that the participants indicated they switched codes in a variety of contexts, mainly informal conversations (family, friends, etc.) but that they try to avoid it in the academic setting. Therefore, code switching may be used mainly to accomplish two tasks: 1) fill a linguistic or conceptual gap, or 2) for other multiple communicative purposes (inclusion, exclusion, friendship, familiarity, rapport, etc.). Code switching, as a natural language function, is neither appreciated nor accepted by many people because it conflicts with what society has come to know as "standard or conventional language". The results obtained in this paper were conducive to a further investigation related to exploring how educators perceive and approach the facilitation of communication in the bilingual classroom as a critical issue for bilinguals' academic success (Garza & Nava, 2007).

Teachers' Perspective

The participants in this study reported that code switching is not an advantage when it comes to learning; they actually consider it to be a limitation that hinders effective communication in the English language. Moreover, teachers stated that code switching is not accepted in their classrooms due to the mindset that it negatively affects elementary students' academic performance. Overall, the participants in this study indicated that they avoid code switching during the delivery of the instruction. Findings also revealed that teachers from the South side of the region under study are not fond of code switching as a possible method of instruction and are completely against it, while the teachers in the North side of the region proved more receptive to it, and seemed to have a different pedagogical approach towards this particular linguistic phenomenon due to their classroom make up (Nava & Garza, 2007).

Data Analysis: Code Switching and Geographical Differences

Fourteen schools were separated into two demographic areas, North and South. There were seven schools representing each area: N=129 participants from the North schools and N=150 participants from the South. The results obtained from each participant were given a numerical value in order to ease the interpretations of the obtained results.

Figure 1 indicates the number of teachers of a specific grade level for each geographical area. The number of participants who did not respond to this question was eight out of 129 from the North and two out of 150 from the South. The number of first grade teachers averaged 32 for both demographics. Overall, the majority of participants from the North taught first grade. The number of surveyed candidates that taught second grade was greater for the South than for the North. The North averaged 23 while the South averaged 30. Third grade averages totaled 23 teachers from the North and 27 from the South.

The gap between the participants that were interviewed from both demographics was the following: The North equaled 26 while the South equaled 30. Fifth grade had the lowest numbers for both demographics, aside from the non-responsive data. The fifth grade showed 17 teachers from the North and 29 from the South.

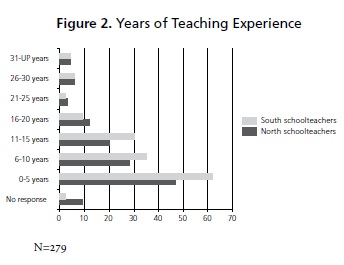

Figure 2 was divided by increments of five due to the number of teachers that responded to the survey. Figure 2 shows that 9 out of 129 participants from the North and 2 out of 150 from the South did not respond to this question. The number of teachers responding to item number one (0-5 years of experience) totaled 47 from the North and 62 from the South. The number of candidates that responded to item number two (6-10 years of experience) added up to 28 from the North and 35 from the South. The number of participants that answered item number 3 (11-15 years of experience) was 20 from the North and 30 from the South.

In essence, the number of teachers with more years of experience was less than those with fewer years of teaching experience. This figure also shows that the participant teachers that answered item number four (16-20 years of experience) were 12 from the North and 9 from the South. Item number five (21-25 years of experience) shows three teachers from the North and two from the South. Item number six (26-30 years of experience) demonstrates that the number of participants was 6 out of 129 from the North and 6 out of 150 from the South. The final category shows that both North and South school districts had 4 teachers with 30 years or more of experience of elementary classroom teaching.

Figure 3 indicates that six out of 129 Northern bilingual/ESL certified teachers did not answer this question, while all Southern teachers did. The number of candidates that identified themselves as Bilingual/ESL Certified totaled 101 out of 129 from the North and 121 out of 150 from the South. The number of teachers that were not bilingual/ESL certified equaled 22 from the North and 29 from the South.

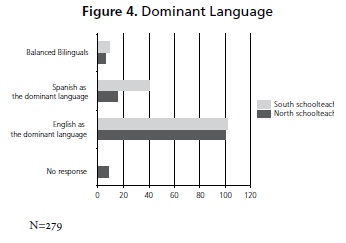

Figure 4 identified the teachers' dominant language; not just its use during the delivery of instruction but in their everyday lives. The number of participants that did not respond was eight out of 129 from the North. The data show that the majority of participants reported that English is their dominant language. For example, 100 out of 129 from the North and 101 out of 150 from the South defined English as their dominant language. The number of informants who reported speaking Spanish was significantly lower compared to those who reported English to be their dominant language. The data show that 15 out of 129 Northern schoolteachers spoke Spanish and 40 out of 150 Southern teachers spoke Spanish as well. The number of participants that identified themselves as bilingual totaled six from the North and nine from the South.

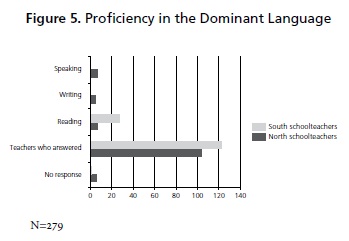

Figure 5 shows the teachers' proficiency in their dominant language (English). The number of participants that did not respond to this question was six from the North and one from the South. The majority reported being proficient in reading, writing, and speaking in the English language as shown in Figure 5. The total number of teachers that answered this question was 104 from the North and 122 from the South. The response to reading (item #2) in their dominant language was 7 from the North and 27 from the South. The response to writing (item #3) equaled 5 out of 129 from the North and none from the South. In response to speaking (item #4), it shows that 7 teachers from the North and none from the South were able to speak only their dominant language. A possible reason that the numbers were so low for individual sections such as reading, writing, and speaking is due to the fact that the majority of teachers indicated they were proficient in all subcategories, not just one.

Figure 6 shows the ethnic make-up of the teachers' elementary classrooms. Eight participants from the Northern schools did not respond to this question, compared to one from the South. Additionally, 102 Northern teachers responded that their classrooms were made-up of Hispanics (item #1) while the South had 146 out of 150 teachers. The ethnic component was Anglos (item #2) in the elementary classroom as indicated by the participants from the North elementary schools (4 out of 129), while the participants from the South responded that 1 classroom out of 150 was Anglo.

The numbers for Asians in both geographical areas were too small to be statistically significant. For example, the participants from the North elementary schools reported one classroom having more Asians than any other ethnic group while the ones from the South did not have any. The participants from the Southern schools reported that they did not have any other ethnic group present (for example, African-American students); however, the candidates from the North indicated having ethnic groups besides Hispanic students such as Anglos, Asians, and/or African-Americans. Fourteen teachers from the schools in the North part of the school district answered that they had more than one ethnic group in their classrooms as shown in the figure above. Overall, there were no responses by teachers from the South that indicated that there was more than one ethnic group in their classrooms.

Data Interpretation

In the realm of teaching and learning, questions about the role of the first language in EFL or ESL classrooms have been commonly addressed. However, there are more questions than answers in the field. Wright (2004, pp. 1-4) considers that teachers have different attitudes toward their students. Moreover, she mentions the importance of those attitudes on the learners' language development. Characteristics such as race, religion, and the kind of native language are usually subject to categorizations and stereotyping. Teachers usually create a particular framework to organize their perceptions once they identify differences among their students.

The result of these differences relies on the students' academic success. However, in order to explain those teachers' attitudes and perceptions, it is necessary to address them from different perspectives. For this reason, Wright (2004) suggests explaining not only the origin of those attitudes but also the effect of them on the learning process.

If teachers are to teach appropriately they must be knowledgeable in the process of framing their attitudes so that they can encourage their students' language learning process. A major finding in this study consisted of analyzing that the more contact teachers have with students of different linguistic backgrounds, the more tolerance they express towards their students' mother tongues as observed in Figure 6. Unfortunately, teachers working in the seven schools located in the South are not as receptive as those teachers from the North schools. This fact has different interpretations. First, the southern schools were observed to serve a highly migrant community (undocumented in the United States) compared to those schools located in the northern suburbs where more resident communities or people with U.S. citizenship live. This may suggest that schools also serve as linguistic gates. That is, educational policies are executed in schools in various ways; one of them is by denying the students' mother tongues and imposing the dominant language and dominant culture. Teachers, then, have to transit their students rapidly from Spanish to English by the third grade. For this reason, the majority of them do not emphasize the teaching of Spanish since the students must be mainstreamed at an early age. This linguistic de-capitalization has negative cognitive effects since students whose mother tongue is different from English do not develop a cognitive and linguistic foundation in their mother tongue (Spanish, in this particular case), resulting in low levels of proficiency and low academic achievement in both languages.

In contrast, teachers working in the schools located on the North side of the school district are more receptive since their students come from different linguistic backgrounds. Moreover, these teachers are not so strongly forced to transit students from their mother tongue to the target language as are those teachers from the south schools. Although code switching is neither promoted nor allowed in schools in the north part of the school district, it is a socially and widely-accepted linguistic form of communication as observed on the playgrounds or in the surroundings of these schools.

In a nutshell, geographically speaking, it was observed that the schools located in the South part along the U.S. border function as linguistic gates where children need to be fully and rapidly assimilated into the mainstream culture (English-only). Even though a significant percentage of teachers reported being bilingual, they were observed employing English as the only language of instruction. Moreover, teachers not only claimed to be certified bilinguals but also considered English to be their dominant language. Regarding the teachers' years of experience, most of the participants reflect that they are in their first years of teaching. This might imply little knowledge of the long-term effects of denying equal education and linguistic opportunities to their students. The results presented above support the research hypothesis presented in this study, suggesting that teachers from the Northern elementary schools are more receptive towards their students' use of code switching due to the makeup of their classrooms than those from the Southern schools, whose student populations are significantly Hispanic.

Conclusions

This paper reviewed previous research findings on bilingual teachers' attitudes toward the use of code switching in their classrooms. The role of the mother tongue is sometimes considered to be a way for teachers to set up and facilitate communication in the EFL/ESL classroom; however, when this phenomenon was studied in highly bilingual settings, codes switching was avoided and prohibited in some cases.

The purpose of this paper was to raise teachers' awareness regarding the importance of their own beliefs and thoughts about a particular group's mother tongue while teaching in bilingual communities. Teachers' beliefs and perceptions toward their students' mother tongue contribute to the delivery of instruction and the success of learning an L2. The diffusion of a particular language policy (English-only) can geographically have more farreaching linguistic consequences. In this study, it was found that there is more resistance towards code switching expressed by the majority of teachers from the south side of the region than those teachers from the north side of the region. According to the geographical data collected, a significant number of teachers from the northern schools have more contact with people of different ethnicity. In contrast, teachers from the southern schools work daily with a representative Spanishspeaking community. Geographically, the teachers from the southern schools have a larger concentration of Hispanics in their classrooms. Needless to say, these teachers have higher political pressure to transit their students from their mother tongue (Spanish) to the target language (English) as fast as they can.

On the contrary, the teachers from the north are more open to diversity due to the geographic distribution of the population in the area. Another important factor to be considered is whether or not the participants from both sides of the area were ESL/Bilingual certified. The findings obtained in the demographic data analysis showed that the majority of the participants from the southern schools were bilingual certified compared to those participants from the northern schools.

Language loss is the result of a language shift situation. Results indicated that bilingual/ESL elementary schoolteachers predominantly speak English even when the population is largely of Hispanic origin since these students first require the use and full proficiency of the Spanish language. In other words, English represents the dominant language for the majority of the participants in this study, although the majority of the participants reported to be bilingual certified. Surprisingly, the participants with a lower proficiency in the Spanish language also reported that they switch codes during the delivery of instructions, which in turn explains the fact that they notice this during the students' oral production. Consequently, the study of code switching as a pedagogical device remains unexplored in this study. Further investigations on the use of code switching, as a pedagogical tool, conducive to help students move from one language to the other (L1 to L2), needs to be addressed.

The fact that students acquire their dominant language, Spanish, at home and English at school may not only suggest why they code switch but may also explain why people have developed a great array of misinterpretations regarding this linguistic form. In addition, the geographical location fosters and motivates the constant linguistic contact between English and Spanish since the Southern U.S. border region constitutes the gate of an increasingly daily influx of Spanish-speakers, resulting in a constant linguistic exchange. In this study, the majority of the teachers (98%) admitted that a vast amount of students switch codes during their earliest years in their classrooms (predominantly during the transition linguistic process [1stthrough 3rdgrades]). This may be the result of the elementary students' second language development process in which they highly rely on their native language in order to develop their target or second language. Overall, the findings in this study revealed the need for developing a thorough and comprehensive investigation on the type of elementary school teachers' preparation and training, especially those who work with bilingual communities without being bilingual (balanced bilinguals) themselves. This fact constitutes the core of this analysis: that teachers' preparation should be supervised closely in order to avoid alienation and discriminatory practices towards students who speak a language other than English.

A stronger emphasis on the preparation of bilingual elementary schoolteachers should be made in order to highlight the importance of being proficient in both languages. Understanding what it is like to be bilingual would provide elementary schoolteachers a better insight into the process of learning/acquiring a second language.

To sum up, the following can be concluded: Due to the accountability era, the participants working in the Southern elementary schools were observed to have more resistance towards their students' use of code switching compared to those teachers from the participating Northern schools. In addition, it was also noticed that there is more social, cultural, political and linguistic pressure on those teachers working closer to the borders than those who work in northern areas. This geographic situation may cause greater tension and pressure for teachers who are held accountable for transiting children faster from L1 to L2, compared to those teachers from the Northern schools who deal with a more diverse school community. Although the study was limited to a single school district, significant observation could be drawn on the results. Further studies could be carried out on teachers' perceptions and attitudes regarding the use of code switching in other areas in order to analyze the impact of this socio-cultural and linguistic phenomenon in different academic settings. For these purposes, code switching should be studied and analyzed by educators or scholars interested in the field rather than as a pure linguistic phenomenon commonly studied by linguists.

References

Albert, M. L., & Obler, L. K. (1978). The bilingual brain: Neuropsychological and neurolinguistic aspects of bilingualism. London: Academic Press, Inc. [ Links ]

Baker, C. (2000). A parents and teachers' guide to bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Bright, W. (1997). International encyclopedia of linguistics (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chaika, E. (1994). Language, the social mirror. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing language shift. Clevedon: England: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Gal, S. (1988). The political economy of code choice. In M. Heller (Ed.), Code switching: Anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives (pp. 243-261). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Garza, E. A., & Nava, G. N. (2005). The effects of code switching on elementary students in a border area of South Texas: A teacher perspective, Part I. Journal of Border Educational Research, 4(2), 97-109. [ Links ]

Garza, E. A., & Nava, G. N. (2007). An exploratory investigation into social variables related to the use of code switching among bilingual children in elementary schools in a South Texas border area, Part II. Journal of Border Educational Research, 6(1), 69-80. [ Links ]

Gumperz, J. (1997). Communicative competence. In N. Coupland, & A. Jaworski (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: A reader's coursebook (pp. 98-159). London: MacMillan Press. [ Links ]

Nava, G. N., & Garza, E. A. (2007). An analysis of elementary teachers' attitudes and beliefs toward their students' use of code-switching in a South Texas border school district. Texas Association of Bilingual Education (TABE) Journal, 9(2), 150-168. [ Links ]

Nava, G. N. (2009). Elementary teachers' attitudes and beliefs towards their students' use of code-switching in South Texas. Lenguaje, 37(1), 135-158. [ Links ]

Yule, G. (2006). The study of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wright, A. S. (2004). Perceptions and Stereotypes of ESL Students. TESL Journal, 10(2), 1-4. [ Links ]

About the Authors

Guadalupe Nancy Nava Gómez holds a PhD in Bilingual Education from Texas A&M University -Kingsville and worked there as Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Bilingual Education. She is currently working as Assistant Professor at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM). Her interests lie in areas of bilingualism, foreign language learning, second language acquisition, and literacy development.

Hilda García received her Master's Degree in Bilingual Education from the Department of Blingual Education at Texas A&M University - Kingsville. She is currently a lecturer in the College of Education at Texas A&M University - Kingsville. Her research interests are mainly focused on bilingualism, language contact and second language learning issues.