Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, as the cause of the COVID-19 disease, brought about morbidity and mortality to a large portion of the world population 1. During this pandemic, the role of nursing professionals was vital due to their social commitment to health care and the humane care of at-risk people, mainly because their actions made it possible to prevent and detect complications early on 2, favoring the preservation of patients' health throughout their stay and up until hospital discharge.

However, the conditions imposed by the pandemic onset a series of complications in the healthcare system and the healthcare professional teams, transcending any coping mechanisms and triggering significant risks to physical health and other dimensions of the human being 3. This increased risk product of stress, insomnia, anxiety, exhaustion, depression, and other symptoms led to the development of multiple diseases 4, which, even though the pandemic was over, are still present through workplace situations such as work overload or the dynamics within some hospital areas. These circumstances cause absenteeism and employee turnover.

Nursing's object of study is care; this includes the care of others and oneself, which affords nursing professionals the tools and skills to promote their health through self-care. According to Giddens 5, health promotion is a process that allows people to gain control over health and improve it, achieving a positive state at the individual, family, and community levels; these dimensions include physical, mental, spiritual, social, environmental, intellectual, and financial conditions. The studies conducted so far found that during the pandemic, nursing professionals engaged in different actions to facilitate their self-care 6, lowering the risk and preventing the onset of diseases typical of health personnel. Per the above, the objective of this review was to identify the self-care strategies implemented by nursing professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and to analyze them in the light of Giddens' theoretical proposal.

Materials and Methods

An integrative, descriptive review was conducted between June and September 2023 under the guidelines of Whittermore and Knalf 7; it was developed in five stages: statement of the problem, research question, literature search, collection, analysis, and presentation of results.

The databases employed were PubMed, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Science Direct, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), and Google Scholar. The population, context, concept (PCC) strategy was used to establish the search criteria. The following DeCS & MeSH terms in Spanish, English, and Portuguese were included along with the Boolean operators: "Pandemic of COVID-19" AND "strategy" OR "self-care" OR "coping behavior" OR "self-esteem" AND "nurses" OR nursing. For search limiters, we had texts published between 2020 and 2023 with abstract and full text available in scientific journals, as well as gray literature, specifically, master's and doctoral theses that addressed the study phenomenon and were published in online repositories, regardless of the methodological design they used. Articles by professionals other than nurses were excluded.

In the selection phase, the documents were organized by title, journal, year of publication, country, methodological design, objective, and self-care actions performed by nurses. The analysis was conducted through in-depth reading in light of the conceptual bases of self-care proposed by Giddens in the health promotion framework 8.

Results

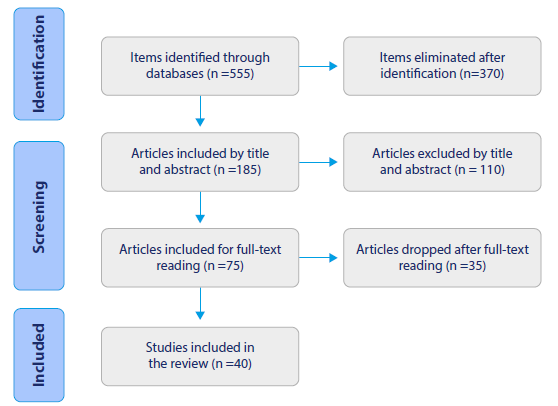

In total, 555 articles were retrieved, of which 370 were eliminated because they did not meet the above criteria, and some appeared twice; 185 documents were reviewed by title and abstract, of which 110 were excluded because they did not address the study's objective. Seventy-five full-text papers were read, and 40 were finally selected for the integrative review because they included self-care strategies performed by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). The information was collected, organized, and analyzed using an ad hoc instrument containing the journal name, authors, year, keywords, descriptors, language, place of research, period of analysis, year of publication, objectives, justification, design, conclusions, and observations.

Source: Adapted from the PRISMA Statement 2020 model (9).

Figure 1 Flowchart for the Selection and Inclusion of Articles (2023)

As for the journals consulted, we shall refer mainly to the International Journal of Nursing Studies, Science and Care, Nursing Research and Education, Rev Latinoamericana de enfermagem, Acta Paulista de Enfermeria, and Nursing Image and Development.

The period of consultation of the selected articles was from 2020 to 2023, and the classification of the languages of publication was 67.5 % Spanish, 20 % English, and 12.5 % Portuguese. The studies were conducted in Brazil, 12.5 %; Spain, 12.5 %; Colombia, 12.5 %; the United States, 10 %; Peru, 7.5 %; Ecuador, 7.5 %; Chile, 7.5 %; China, 5 %; Costa Rica, 5 %; Argentina, 5 %; Panama, 5 %, and Cuba, Mexico, United Kingdom, and Poland with 2.5 %. These studies all accounted for different methodological designs (Table 1).

Table 1 Articles Included for Integrative Review

| Authors | Country | Year | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lahite-Savón et al. 2 | Cuba | 2020 | Literature review |

| Carlos-Cajo et al. 10 | Peru | 2020 | Literature review |

| Franco Coffré et al. 11 | Ecuador | 2020 | Cross-sectional study |

| Holguín Lezcano et al. 12 | Colombia | 2020 | Theoretical review |

| Fernández et al. 13 | USA | 2020 | Systematic review |

| Dong et al. 14 | China | 2020 | Bibliographic review |

| Noreña García 15 | Colombia | 2020 | Qualitative study |

| Castañeda et al. 16 | Brazil | 2020 | Theoretical review |

| Martínez-Esquivel 17 | Costa Rica | 2020 | Integrative review |

| Barreto Bernardo et al. 18 | Peru | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Sánchez-De la Cruz et al. (19 | Spain | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Zheng et al. 20 | China | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Silva et al. 21 | USA | 2021 | Integrative review |

| Peñafiel-León et al. 22 | Ecuador | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Riedel et al. 23 | USA | 2021 | Bibliographic review |

| Pieró Salvador et al. 24 | Spain | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Valencia-Gutiérrez et al. 25 | México | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Quiroz Ubillus et al. 26 | Peru | 2021 | Integrative review |

| Henao-Castaño et al. (27) | Colombia | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| Sepúlveda et al. 28 | Chile | 2021 | Descriptive study |

| Rodríguez Hernández et al. 29 | Colombia | 2021 | Systematic review |

| Burbano 30 | Brazil | 2021 | Integrative review |

| Arpacioglu et al. 31 | USA | 2021 | Cross-sectional study |

| López Olmo 32 | Spain | 2021 | Bibliographic review |

| Rodríguez et al. 33 | Spain | 2022 | Bibliographic review |

| Macaya et al. 34 | Chile | 2022 | Bibliographic review |

| Vega et al. 35 | Costa Rica | 2022 | Descriptive study |

| King et al. 36 | UK | 2022 | Quantitative study |

| Uribe-Tohá et al. 6 | Chile | 2022 | Cross-sectional study |

| Sierakowska et al. 37 | Poland | 2022 | Cross-sectional study |

| Brito Ayala et al. 38 | Ecuador | 2022 | Case studies |

| Bazan et al. 39 | Argentina | 2022 | Cross-sectional study |

| Vieira et al. 40 | Brazil | 2022 | Cross-sectional study |

| Zambrano Bohórquez et al. 41 | Spain | 2022 | Observational study |

| Jonhson et al. 42 | Argentina | 2022 | Cross-sectional study |

| Barrios et al. 43 | Panama | 2022 | Integrative review |

| Fernández Rodríguez et al. 44 | Panama | 2023 | Cross-sectional study |

| Gómez Carvajal et al. 45 | Colombia | 2023 | Ethnographic study |

| Vargas et al. 46 | Brazil | 2023 | Scoping review |

| Silva Barbosa et al. 47 | Brazil | 2023 | Integrative review |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

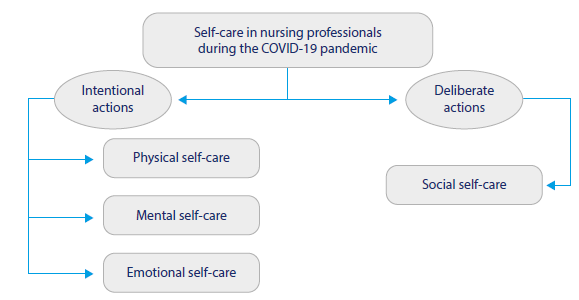

Based on an in-depth reading of the selected articles and the study's objective, the results are presented in light of the conceptual bases of self-care proposed by Giddens in the health promotion framework 8. The results suggest that self-care is built from the generation of habits or behaviors, which are divided into two categories: (a) intentional actions performed by people without any beforehand reflection or questioning and (b) deliberate actions where reflection and significant experiences lead to the incorporation of self-care guidelines that were not previously in place (Figure 2).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2 Self-care in Nursing Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Intentional Actions

Physical self-care 2,6,13,21-22,28,33-35,37-45,47: It refers to the biological, within which the following factors were overseen: sleep quality and hygiene, relaxation routines before sleep, the establishment of daily stretching routines and concomitant diaphragmatic breathing, proper hydration, the performance of physical exercise such as aerobic resistance training (running, swimming, rope jumping, walking, dancing, stairs climbing, endurance races, and the like). Another critical aspect was the incorporation of foods such as vegetables, fruits, cereals, tubers, legumes, and meats, which improve satiety and prevent eating disorders, regulate blood glucose levels, and enhance work performance; also, food eating schedules and manners aid in the eradication of harmful habits through an action plan.

Other self-care actions related to pandemic-specific aspects were i) strictly following personal protection measures, ii) keeping going-out clothes apart from work clothes, iii) incorporating and complying with home leaving and entering protocols, iv) avoiding crowded places, and v) monitoring underlying conditions and active surveillance of symptoms, in addition to actively gaining knowledge about COVID-19, its symptoms, prevention, and mechanisms of transmission and treatment.

Mental self-care 10-12,15-16,19,21-31,33-34,36-38,40,43,45-47: This is related to the cognitive, i.e., cultivating the mind. Aspects such as reading, learning something new, looking after your thoughts, keeping an active mind, exercising the brain, assertive communication, listening to music, reading a book, and video-chatting with a friend or family member fall within this type of care, in addition to relaxation activities such as meditation, prayer, yoga, dancing, having a conversation with family and friends to relieve stress, support, renewal of thoughts and self-motivation to face the pandemic. Furthermore, the need to get help from other health care professionals to reduce emotional stress, seek leisure activities, and keep the mind occupied with activities that would distract it from information about the pandemic was identified 14. Daily routines were rearranged to include leisure activities that would forge well-being, such as time for meditation and relaxation during working hours; resorting to external elements for rest, such as aromatherapy, music therapy, and dim light, among others, worked very well in pursuing this type of care.

Emotional self-care 10-16,19-20,22-26,29-34,36-37,39-41,43,46,47: This is the care of emotions, the importance of acknowledging them, not avoiding them in an attempt to feel good. The following activities were identified within this category: daily breathing exercises, focused meditation (mindfulness) before starting and upon completion of caregiving activities, and recognizing stress helped to have better emotional stability, as did seeking psychological help. Four-step cognitive processing therapy was also included: education, information, development of skills, and changes in beliefs through online yoga and Pilates workshops, including psychological therapy sessions via video calls. Recognizing and expressing feelings and emotions and cognitive restructuring through a positive re-evaluation of a stressful situation led to pursuing new personal interests, skill enhancement, and creative talents.

Deliberate actions

Social self-care 11-14,20,23,26-30,33-35,37-38,42-43,45-47: All those actions that were implemented at the time to prevent the spread of COVID-19 to an entire family, social and work circle. In this vein, chief nurses prepared a series of personal actions to encourage their work teams. These actions were grouped into three categories:

Providing instructions: The leaders would state clearly the organization's purpose and identify the steps needed to address problems and challenges, including clear and timely communication, information, and training, strengthening social and work support sources and relationships, and emotional regulation through self-control.

Giving meaning: The leaders would explain the actions necessary to achieve a healthy work environment through dialogue and reflective self-observation about any experiences lived. This was done to establish some boundaries between work and home. Finally, the periodic application of mental health screenings, such as the symptom questionnaire (SRQ) and Maslach's Burnout Inventory, are considered vital in the early detection and treatment of these problems in the nursing staff.

Generating empathy: The leaders employed empathetic language to recognize the problems and challenges people were facing and provided emotional support and guidance in developing a personalized self-care plan. Moreover, they helped enhance the skills that led to developing self-compassion and recognizing the hard work done to build collective care.

Discussion

The self-care actions identified and implemented by nurses during the pandemic led to the deduction that all were aimed at preventing illness and lessening attrition by recognizing stress and strengthening resilience. Studies during the pandemic showed that perceived stress decreased as resilience increased 29; factors such as age, expertise, area of specialization, knowledge in administration, and hospital preparedness for COVID-19 showed a positive relationship, which impacted the provision of safe care. Thus, resilience was positively associated with quality of care and job satisfaction 22, reducing the effects of fatigue on nurses' job satisfaction, employee turnover, and quality of care. On the other hand, a lack of resilience was negatively connected to the intention to leave one's job. However, resilience should not be regarded as an individual duty but as a collective and organizational one 48.

Among the intentional actions that nurses implemented following their reflection and experience are mental self-care activities, such as communication with family and friends, seeking distractions and company, searching for individual and collective well-being, renewing thoughts and self-motivation that helped them to face the pandemic and high-stress situations 42. In this vein, it is essential to note that nurses prioritized their humanistic sentiments, professional duty, solidarity, and the obligation to offer their knowledge and care over the fear of contagion, stress, and psychological suffering experienced 32; this had a positive effect that turned into preventive factors against burnout syndrome, a disorder derived from high levels of emotional fatigue, low personal fulfillment and depersonalization 42.

Emotional self-care is based on recognizing emotions and not avoiding them in an attempt to feel good. It was shown that ensuring an adequate work environment, promoting active breaks, fostering team spirit, practicing empathy with coworkers, and ensuring that every professional's hard work did not go unnoticed is essential for adequate emotional self-care 49. The implementation of strategies that helped nurses to mitigate stressors, specifically social support, organizational support, self-management of emotions, identification of harmful habits, psychotherapy 40, emotional release techniques, cognitive restructuring, and psychoeducation, promoted dialogue and reflective self-observation of experiences in the construction of collective care 13.

Among the actions implemented by the leaders concerning the reduction of absenteeism were emotional regulation through the self-control of emotions, fair distribution of the workload, avoiding prolonged working hours, and the provision of personal protective equipment 22. The above was oriented toward the prevention of burnout syndrome caused by stress, anxiety, and different pandemic-related health problems. The continuous application of screening was essential for the early detection of mental health problems in the nursing staff 50, which led to the formation of multidisciplinary mental health teams, including psychiatrists, psychologists, and nurses in charge of mental health within the organization.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic brought global health consequences on individuals and health professionals, leading to worker burnout syndrome and job desertion. To solve these issues, nursing professionals identified and implemented different self-care actions that helped reduce the effects derived from such a context. Among the self-care actions identified are intentional ones aimed at physical, mental, and emotional health care and deliberate actions oriented to health care at the social level. Aspects such as resilience, coping, enthusiasm, willingness, and emotional self-management played a crucial role in implementing self-care in nursing professionals.

The actions analyzed, although applied during the time of the pandemic, could also be implemented in current work situations, especially where there is work overload, stressful situations, anxiety, or burnout syndrome; these strategies aim at mitigating the adverse effects on healthcare personnel, improving working conditions, strengthening positive relationships within organizations and preventing the onset of diseases typical of professional practice under inappropriate scenarios.