Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.14 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-1.iapb

Is it Acceptable for a Psychologist to Break A Young Client's Confidentiality? Comparing Latin American (Chilean) and Western European (French) Viewpoints*

¿Es aceptable para un psicólogo romper la confidencialidad de un joven cliente? Una comparación entre las perspectivas latinoamericana (chilena) y europea occidental (francesa)

Cecilia Olivari**

Catholic University of Maule, Talca, Chile

Maria Teresa Munoz Sastre

Mirail University, Toulouse, France

Paul Clay Sorum

Albany Medical College, Albany, NY

Etienne Mullet

Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, France

*Artículo original resultado de investigación

**E-mails: cecilia.olivari@yahoo.es, mtmunoz@univ-tlse2.fr, SorumP@mail.amc.edu, etienne.mullet@wanadoo.fr

Received: September 16th, 2013 | Revised: August 14th, 2014 | Accepted: August 14th, 2014

To cite this article

Olivari, C, Munoz, M. T., Sorum, P. C., & Mullet, E. (2015). Is it acceptable for a psychologist to break a young Client's Confidentiality? Comparing Latin American (Chilean) and Western European (French) viewpoints. Universitas Psychologica, 14(1), 231-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-1.iapb

Resumen

En el presente estudio, fueron examinadas y comparadas las perspectivas de adultos chilenos y franceses respecto a la ruptura de la confidencialidad, frente al tema del consumo de drogas ilícitas. A 12 psicólogos chilenos, 143 adultos chilenos, y 100 adultos franceses se les presentó una serie de 64 viñetas, en las cuales un psicólogo conversa con su joven cliente que presenta consumo de drogas. Estas viñetas fueron compuestas de acuerdo a un diseño factorial de 6 factores intra-sujeto: la edad del cliente, la peligrosidad de la droga, el tiempo que lleva consumiendo la droga, si el cliente está de acuerdo en recibir tratamiento para la adicción, la estabilidad de su familia y si el psicólogo consulta a un experto antes de informar a la familia. Los resultados evidenciaron cuatro tipo de posiciones diferentes: "Nunca aceptable" (20%), "Siempre aceptable" (27%), "Principalmente dependiendo de la edad del cliente" (20%), y "Principalmente dependiendo del tipo de problemas familiares" (33%). Un alto porcentaje de participantes chilenos expresaron la perspectiva llamada "nunca aceptable", en comparación a los participantes franceses, y un alto porcentaje de participantes franceses expresaron la perspectiva "dependiendo de la edad del cliente", comparado con los participantes chilenos. Los participantes chilenos expresaron posiciones que son generalmente compatibles con el código de ética chileno.

Palabras clave: Confidencialidad; Chile; Menores; Francia

Abstract

The views of Chilean and French adults concerning breaking confidentiality about illicit drug consumption were examined and compared. Twelve Chilean psychologists, 143 Chilean adults, and 100 French adults were presented with a series of 64 vignettes of a psychologist told by her young client that he is using illicit drugs. They were composed according to a six within-subject factor design: client's age, dangerousness of the drug, duration of drug consumption, whether he agreed to be treated for addiction, stability of his family, and whether the psychologist consulted an expert before informing the family. Four qualitatively different personal positions were found, called Never acceptable (20% of the participants), Always acceptable (27%), Mainly depends on client's age (20%), and Mainly depends on family problems (33%). A larger percentage of Chileans expressed the never acceptable view compared to French lay people, and a larger percentage of French expressed the mainly depends on client's age view, compared to Chilean lay people. Chilean psychologists infrequently endorsed positions that are not fully compatible with the Chilean code of ethics.

Keywords: confidentiality; psychological practice; drug intake; minors

The study examined the views of lay people and psychologists in Latin America, namely Chile, regarding the breaking of confidentiality by psychologists who realize that their young clients (i.e., adolescents and young adults) consume illicit drugs on a regular basis. It compared these views with those of Western European people, namely in France (Munoz Sastre, Olivari, Sorum, & Mullet, 2013).

Confidentiality is essential for appropriate counseling and good psychological therapy (Donner, Van de Creek, Gonsiorek, & Fisher, 2008; Fischer, 2008). It is necessary for the establishment of trust between psychologists and clients. Without such trust, clients may be reluctant to disclose all pertinent information especially about irrational thoughts, inappropriate emotions, and abnormal behaviors (Stone & Isaacs, 2003). Without complete disclosure, psychologists may not be able to counsel clients in an appropriate way, make accurate diagnoses, undertake effective psychotherapy, and arrange for appropriate follow-up (e.g. Ormrod & Ambrose , 1999). Moreover, trust is needed to achieve client-psychologist relationships that may be therapeutic. The breaching of confidentiality would risk alienating clients in need of psychological care. The importance of confidentiality is, therefore, recognized in codes of professional deontology elaborated by psychological associations (as described below).

Confidentiality may, however, have its limits. When psychologists suspect that their clients' behaviors will put themselves or other persons at risk, they must decide whether to maintain confidentiality or to break it in order to try to protect the person her/himself or the other persons (whether by warning them directly or by alerting the authorities). In such cases where clients' rights compete with the rights and well-being of clients' relatives and others, decisions concerning breaking confidentiality can be critical. Since the risky health behaviors of adolescents have become a serious public health problem (U. S. Department of Health and Human Services , 2010), it is no surprise that psychologists consider confidentiality dilemmas as the most frequent dilemmas they encounter in their practices (Pettifor & Sawchuk, 2006; Pope & Vetter, 1992).

Psychological Associations' Views about Confidentiality

According to the American Psychological Association, psychologists "have a primary obligation to take reasonable precautions to protect confidential information obtained through or stored in any medium, recognizing that the extent and limits of confidentiality may be regulated by law or established by institutional rules or professional or scientific relationships". APA also states that psychologists "disclose confidential information without the consent of the individual only as mandated by law or where permitted by law for a valid purpose such as to ... protect the client/patient, psychologist, or others from harm" (see also Gustafson & McNamara, 2004).

In Chile, patient confidentiality is protected by the Code of Ethics of the Chilean Association of Professional Psychologists (Colegio de Psicólogos de Chile, 1999). Article 5.2 states that psychologists must respect the confidentiality of any information regarding the patients, whether it has been obtained through verbal exchange with them or through other procedures. It is, however, considered legitimate to breach confidentiality in some cases that include court decisions, and when the (responsible) patient gives the psychologist explicit permission to share information. Chilean and US codes are therefore essentially similar.

Professionals' Views Regarding Confidentiality in the Case of Minor Clients

Researchers have conducted two types of studies of professionals' views on confidentiality in the case of minors. In the first set, they (a) examined practicing psychologists' views about the perceived importance of diverse circumstances at the time of considering whether to break or not to break confidentiality, and (b) through factor analysis, delineated underlying constructs characterizing these circumstances. Sullivan, Ramirez, Rae, Peña Razo, and George (2002) found that, for 74 US pediatric psychologists, the four most important considerations were (a) protecting the adolescent (M = 4.66, out of 5), (b) apparent seriousness of the risk-taking behavior (M = 4.61), (c) intensity of risk-taking behavior (M = 4.61), and (d) duration of risk-taking behavior (M = 4.61). Through exploratory factor analysis, they found evidence for two underlying constructs (a) negative nature of the behavior (e.g., intensity of risk-taking behavior), and (b) maintaining the therapeutic process (e.g., not disrupting the process of therapy).

Sullivan and Moyer (2008) expanded this survey to a larger sample of US school counselors (N = 204). The four most important considerations they found were highly similar in nature and importance to the ones found in the previous study. Their exploratory factor analysis, however, revealed not only the previous two factors but also two new ones: (c) legal issues (e.g., complying with school district policies), and (d) student characteristics (e.g., age). Similarly, Duncan, Williams and Knowles (2012) inventoried the factors that Australian psychologists ( N = 264) take into account when making the decision to break confidentiality and found almost the same four underlying constructs. In none of these studies were clients' age and clients' gender considered as important considerations.

In a second set of studies, researchers used scenarios that depicted concrete situations in which adolescents consumed alcohol (or illicit drugs), behaved in an illegal way, or had sexual relationships. Comparing psychologists' responses to these scenarios allowed these authors to assess which circumstances had an effect on psychologists' decision about confidentiality. Isaacs and Stone (1999) examined the way a sample of 637 US school counselors handled confidentiality when working with students. Counselors were instructed to rate the extent to which they considered, in each scenario, that breaking confidentiality was appropriate. Two aspects of the situations had an impact on their willingness to break confidentiality; (a) the perceived level of dangerousness of the behavior and (b) the young client's age. Isaacs and Stone (2001) expanded the same kind of survey to US mental health counselors ( N = 608) and replicated their previous findings. Not surprisingly, in cases of tobacco smoking or shoplifting, only about 10% of counselors considered it appropriate to break confidentiality, but about 60% considered it appropriate to break confidentiality in the case of an adolescent's regular use of crack cocaine. Stone and Isaacs (2003) compared US school counselors' views regarding confidentiality before and after the tragic shootings at Columbine High School in April 1999. Counselors' willingness to break confidentiality was lower after the shootings than before them, which can be explained by counselors' belief that stricter respect for confidentiality on their part would make troubled students more willing to disclose their psychological problems.

Rae, Sullivan, Peña Razo, George and Ramirez (2002) used scenarios to examine the extent to which US pediatric psychologists (N = 92) find it ethical to report their young clients' risky behaviors to their parents. Ratings were higher when health damaging behaviors such as tobacco smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and sexual behavior were perceived as more intense, more frequent, and of longer duration. For instance, when adolescents had smoked marijuana once several months ago, the rating was 1.56 (on a scale from 0 = unquestionably anti-ethical to 6 = unquestionably ethical), whereas when adolescents have been smoking marijuana nearly daily for the last year, the rating was 3.51. When adolescents used hallucinogens (e.g., LSD) nearly daily for the last year, the rating was 4.35. In other words, an Intensity X Frequency/Duration interaction was present. Moyer and Sullivan (2008), working with a sample of 204 US school counselors, and Rae, Sullivan, Peña Razo, and Garcia de Alba (2009), working with a sample of 78 US school psychologists, reported similar findings. It must be emphasized, however, that, in all three studies, strong individual differences were present; that is, psychologists or counselors did not interpret ethical standards in the same way and did not fully agree on the circumstances in which it was required, from an ethical point of view, to break confidentiality and notify parents of their child's potentially health-damaging behaviors (see also Chevalier & Lyon, 1993).

Moyer, Sullivan and Growcock (2012) examined US school counselors' views (N = 378) about the breaking of confidentiality and the reporting of students' negative behaviors to school administrators. Three dimensions were found to have an impact on willingness to report: (a) direct observation of the negative behavior, (b) occurrence of the behavior on school grounds (during school hours), and (c) existence of an official policy guiding school counselors' actions.

In summary, in all studies published until now, most professionals agreed that protecting the adolescent's health is generally more important than maintaining confidentiality (Rae et al., 2002). These professionals responded in accordance with the sometimes-conflicting four principles of bioethics (Beauchamp & Childress, 2001). First, they wanted to respect the autonomy principle of bioethics; that is, they were unwilling to break confidentiality on the basis of minor transgressions or unproved facts. Second, they wanted to respect the non-malevolence principle; i.e.; not to damage their therapeutic relationship with their young client. Third, they wanted to respect the benevolence principle; they found it acceptable to breach confidentiality when their young client's health was endangered by the risky behavior and when the parents' collaboration seemed needed to correct the situation. Fourth, they were willing to respect the justice principle; they were unwilling to consider the client's demographic characteristics as relevant at the time of deciding (even if the age factor has been empirically shown to affect their judgments).

Lay People's Views Regarding Confidentiality in the Case of Minor Clients

Munoz Sastre, Olivari, Sorum, and Mullet (2013) examined the views of French minors and adults (N = 261) concerning breaking confidentiality about illicit drug consumption by adolescents and young adults. In this study, adolescents aged 15-16, quasi-adults aged 17-18, and adults aged 19-75 were presented with a series of 64 vignettes of a psychologist told by her young male client that he is using illicit drugs. Vignettes were composed according to a six within-subject factor design: client's age (minor or adult), the dangerousness of the drug, duration of drug consumption, whether the client agrees to be treated for addiction, stability of his/her family, and whether the psychologist consulted an expert before informing the family. Through cluster analysis, four qualitatively different personal positions were found, called Never acceptable (15% of the participants), Always acceptable (22%), Mainly depends on client's age (26%), and Mainly depends on family problems (37%). Few differences were found between minor and adult participants except that adults endorsed the Always acceptable view more frequently than did minors.

The Present Study

The present study was aimed at replicating, on a sample of lay people and practicing psychologists living in Chile, the findings from the study conducted by Munoz Sastre et al. (2013). The study was cross-cultural in character; that is, a sample of French lay people was also included in the study. Comparing the views of people from very different countries can lead to important insights, as illustrated in the early studies by Colnerud, Hans-son, Salling, and Tikkanen (1996), Dalen (2006), Lindsay and Colley (1995), as well as Sinclair and Pettifor (1996).

The present study also focused on the considerable individual differences in participants' responses already reported (e.g., Rae et al., 2009). These differences were not considered as just simple linear variations along response scales. They were considered as reflecting participants' basic philosophical positions regarding the appropriateness of breaking confidentiality in general or under specific circumstances. As suggested by Rae (2002), "we not only need to ask psychologists what they would do in these situations; we also need to ask why they would do it". As a result, the aim of the present study was, as in Munoz Sastre et al. (2013), to uncover in a very analytical way the diverse personal philosophies that can co-exist in a society regarding the issue of "psychological confidentiality" when clients are young minors.

Hypotheses and Research Question

We had two hypothesis and one research question. The first hypothesis was that the same four contrasting philosophical positions evidenced in Munoz Sastre et al.'s (2013) study would be found among Chilean lay people and psychologists: Never acceptable, Always acceptable, Mainly depends on client's age, and Mainly depends on family problems. The second hypothesis was that the two positions that are not compatible or not fully compatible with the Chilean Code of Ethics -- Always acceptable and Mainly depends on family problems — would not be found among the practicing psychologists or would not be found as frequently as among the lay people. Our research question was: Are there important differences between Chilean and French lay people regarding the confidentiality issue?

Method

Participants

Three samples of participants were included: (a) licensed psychologists working in the area of Concepcion, Chile, (b) lay people living in the areas of Concepcion and Talca, Chile, and (c) lay people living in the area of Toulouse, France. All participants were unpaid volunteers recruited by two of the authors (CO and MTMS). The sample of psychologists was composed of 9 females and 3 males aged 30-50 (M = 36.75, SD = 5.77). The sample of Chilean lay people was composed of 79 females and 64 males aged 18-69 (M = 29.38, SD = 12.47). The sample of French lay people was composed of 47 females and 53 males aged 18-70 (M = 33.31, SD = 15.14).

Material

The material consisted of 64 cards containing a story of a few lines, a question, and a response scale. Vignettes were composed according to a six within-subject factor design: (a) the young client's age (1617 years vs. 19-20 years), (b) the dangerousness of the drug that is consumed (soft drugs only vs. hard drugs), (c) duration of drug consumption (about six months vs. about three years), (d) whether the young client agrees to be treated for addiction (acceptance vs. non-acceptance), (e) young client's family (united family vs. troubled family), and (f) whether the psychologist has consulted an expert before informing the family (call to an expert, no call), 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2. Other information was held constant: notably, all clients were males, and in each case the psychologist decided to call personally the young client's family in order to inform the mother or the father that his/her son consumed illicit drugs. No specific drugs were mentioned in the vignettes.

As an example of vignette is the following: "Mr. Lopez Ramirez, a psychologist, saw Aaron N. L., who is 20 V years old, for an office visit. In the course of the visit, Aaron revealed to him that he has been using drugs for about three years. The particular drug he uses is categorized as a 'hard' drug. Aaron did not want to indicate how he got ahold of the drug.

After a long discussion with Aaron, Mr. Lopez managed to bring Aaron to agree to possible treatment to stop taking drugs. Aaron's family is troubled; it is known to the city's Social Services. After consulting by telephone a colleague who specializes in addiction, Mr. Lopez decided to telephone Aaron's parents to inform them that he is using drugs."

Under each vignette were a question—"To what extent do you believe that the decision made by the psychologist is acceptable?"—and a large 13-point linear response scale with anchors of "Not acceptable at all" (0) and "Completely acceptable" (12).

Two examples are given in the Appendix. Cards were arranged by chance and in a different order for each participant. Finally, participants answered additional questions about age, gender, and educational level.

Procedure

The site was, for the lay people, either their home or a vacant university classroom, and for the professionals, their office or a vacant hospital room. Each person was tested individually. The session had two phases. In the familiarization phase, after the experimenter explained what was expected, the participant read a subset of 16 vignettes (randomly selected), was reminded by the experimenter of the items of information in it, and indicated on the response scale the acceptability of breaking confidentiality. After completing the 16 ratings, the participant was allowed to look back at, compare, and change his or her responses. In the experimental phase, the participant worked at his or her own pace, but was not allowed to look back at and change previous responses. In both phases, the experimenter made certain that each subject, regardless of age, educational level, or professional status, was able to understand all the necessary information before making a rating.

Both lay people and professionals took 30-45 minutes to complete both phases. The experimental phase went quickly because they were already familiar with the task and material. No lay person or professional complained about the number of vignettes or about their credibility.

Results

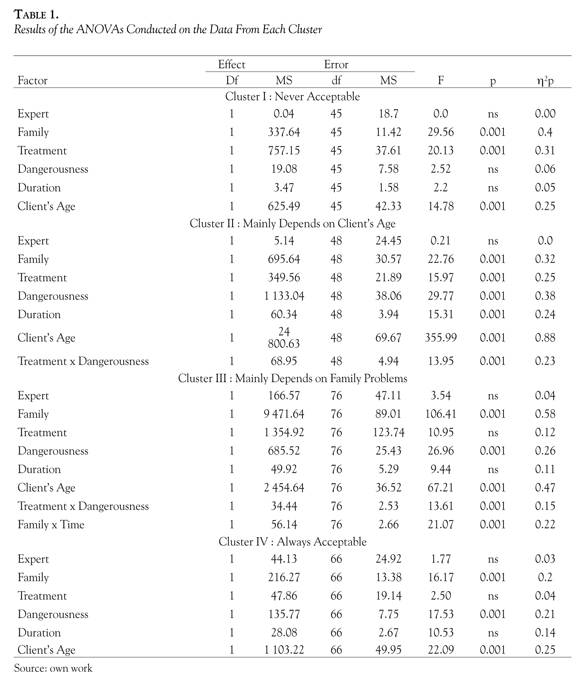

A cluster analysis was conducted on the whole set of data gathered in Chile and in France (Hofmans & Mullet, 2013). A four-cluster solution was selected. The first cluster ( N = 52) was the expected Never acceptable cluster. As can be seen in Figure 1 (top panels), the participants' mean acceptability rating was very low (M = 1.78, SD = 1.23). Forty-two percent of psychologists, 25% of Chilean lay participants, but only 11% of French lay people were in this cluster (p < 0.001). Participants' mean age was 27 years. An ANOVA was conducted on the raw data with an Age x Dangerousness x Duration x Treatment x Family x Expert, 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 design. Results are shown in Table 1. The age, treatment, and family effects were significant but their effect sizes were small.

The second cluster was the expected Mainly depends on client's age cluster (N = 51). As can be seen in Figure 1 (bottom panels), participants' mean acceptability rating was rather high ( M = 6.98, SD = 1.2). Forty-two percent of psychologists, 30% of French lay participants, but only 11% of Chilean lay participants were in this cluster (p < 0.001). Participants' mean age was 31 years. When the client was a minor (M = 9.79), ratings were higher than when he was a young adult ( M = 4.16). In addition, (a) when he consumed hard drugs ( M = 7.58), ratings were higher than when he consumed soft drugs ( M = 6.31), (b) when he refused any treatment (M = 7.31), ratings were higher than when he agreed to be treated (M = 6.64, not shown), and (c) when his family was a united one ( M = 7.45), ratings were higher than when it was a troubled one ( M = 6.5). One interaction was present. The effect of treatment was stronger when the drug was hard (8.06 - 7.09 = 0.97) than when it was soft (6.56 -6.19 = 0.37).

The third cluster was the expected Mainly depends on family problems cluster (N = 83). As can be seen in Figure 2 (top panels), participants' mean rating was close to the middle of the acceptability scale (M = 5.88, SD = 1.19). Except for one psychologist, participants in this cluster were all lay people (35% of the Chilean and 32% of the French). Participants' mean age was 29 years. When the client's family was a united one (M = 7.3), ratings were higher than when it was a troubled one (M = 4.53). Furthermore, (a) when the client was a minor (M = 6.62), acceptability ratings were higher than when he was an adult (M = 5.21), (b) when he consumed hard drugs ( M = 6.29), ratings were higher than when he consumed soft drugs ( M = 5.54), and (c) when he refused any treatment (M = 6.44), ratings were higher than when he agreed to be treated (M = 5.39, not shown). Several interactions were present. The effect of treatment was stronger when the drug was hard (6.9 - 5.68 = 1.22) than when it was soft (5.99 - 5.1 = 0.88). The effect of duration was stronger when the family was united (7.51 - 7.1 = 0.41) than when it was troubled (4.54 - 4.53 = 0.01).

The fourth cluster (N = 69) was the expected Always acceptable cluster. As can be seen in Figure 2 (bottom panels), participants' mean acceptability rating was very high (M = 10.02, SD = 1.2). Except for one psychologist, the participants in this cluster were, as in Cluster II, lay people (29% of the Chilean and 27% of the French). The age, type of drug, and family effects were significant, but their effect sizes were, as in Cluster I, small. Participants' mean age was 37 years. Overall, participant's mean age was significantly different from one cluster to the other, F(3, 251) = 7.72, p < 0.001.

An ANOVA was also conducted on the whole set of data from the lay participants. The design was Country x Gender x Participant's Age (less than 25 years vs. more than 24 years) x Client's Age x Dangerousness x Duration x Treatment x Family x Expert, 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2. Participant's age was significant, F(1, 22) = 13.68, p < 0.001. Acceptability was higher among younger participants ( M = 5.84) than among older participants ( M = 5.32). The Country x Time interaction was significant, F(1, 22) = 33.76, p < 0.001. The time effect was stronger among the French (7.27 - 6.24 = 1.03) than among the Chileans (6.52 -6.29 = 0.23). The Country x Client's age was significant, F(1, 22) = 22.83, p < 0.001. The age effect was stronger among the French (8.2 - 7.3 = 2.9) than among Chileans (7.08 -5.73 = 1.35). Finally, the Severity x Duration interaction was significant, F(1, 22) = 28.4, p < 0.001. Duration effect was stronger when severity was high (6.93 - 5.86 = 1.07) than when it was low (5.93 - 5.46 = 0.57).

Discussion

The first hypothesis — that the four contrasting philosophical positions found among French people by Munoz Sastre et al. (2013) would be found among Chilean people — was supported by the data. Participants endorsing the never acceptable position tended to give absolute priority to the client's autonomy, and to the non-malevolence principle, as far as this principle is interpreted as not doing anything that can result in having immediate negative consequences for the client (e.g., interrupting the therapeutic process). Participants endorsing the mainly depending on family problems position tended to give priority to the benevolence principle and to balance client's autonomy and parents' responsibility. When the family was not able to help the young client, the breaking of confidentiality was not considered as acceptable. Participants endorsing the mainly depending on client's age position tended to give absolute priority (a) to the client's autonomy and to the non-malevolence principle when the young client was adult, and (b) to parents' responsibility and to the benevolence principle when

the young client was minor. Finally, participants endorsing the always acceptable position tended to give absolute priority to the parents' responsibility, and to the benevolence principle, as far as this principle is interpreted as doing anything that can result in having positive consequences for the client (e.g., initiating a therapeutic process under parental control). This findings is fully consistent with early finding on Chilean people's views regarding medical confidentially (Olivari et al., 2011).

Chilean lay people could be divided into four clusters: Mainly depends on family problems (35%), always acceptable (29%), never acceptable (25%), and mainly depends on age (11%). Like the French, they were clearly divided in their views on this aspect of breaking confidentiality. Chileans and the French lay people both in this study and in that of Muñoz Sastre et al. (2013) differed in two ways. First, a larger percentage of Chileans were in the Never acceptable cluster (25%) compared to French lay people in this study (10%) or in the study by Muñoz Sastre et al. (2013). One may wonder whether the practice of the confidential confession (among Catholics) that is still widespread in Chile may have played a role. Second, a larger percent of French participants were in the Mainly depends on client's age cluster (30% in the current study, 26% in the study of Muñoz Sastre et al., vs. 11% of Chileans). Chileans did not appear to think that patient's age was important, although whether a higher client age would have shown less or more difference between French and Chilean lay people is unknown.

The second hypothesis — that psychologists would infrequently endorse the two positions that are not fully compatible with the Chilean code of ethics — can be considered as largely supported by the data since only two psychologists (out of 12) did so, one in the Always acceptable cluster and one in the Depends mainly on family problems cluster. Five psychologists endorsed the never acceptable position, which was not in contradiction with the Chilean code of ethics because in no cases did the young clients put anybody else than himself in danger, and no tribunal was involved. Five psychologists endorsed the Depends mainly on client's age position, which also was not in contradiction with the code

of ethics because the code is silent about minor clients. This tendency to oppose breaking of confidentiality, at least for adults, is largely consistent with Chilean physicians' views regarding medical confidentially (Olivari et al., 2011). The positions taken by these clusters of participants—who, aside from the Chilean psychologists, were lay people without medical training— reflect remarkably well the basic principles of bioethics (Beauchamp & Childress, 2001).

In addition to being related to participant's training in clinical psychology, these basic ethical positions were related to participants' other characteristics. Younger participants, more frequently than older participants, endorsed views that favor young clients' autonomy and the non-malevolence principle than views that favor parents' autonomy and the benevolence principle, and this trend was independent of participants' gender. This may be explained by the fact that young participants, not surprisingly, more strongly identified themselves with the adolescents (and their rights and immediate interests) than with parents.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Firstly, participants were limited to people in the regions of Talca and Concepcion, Chile, and Toulouse, France, and the subsample of psychologist was small, which illustrates how difficult it is, in some countries, to involve professionals in such studies (see also Guedj et al., 2006, 2009). Generalizations to Chilean psychologists as a group, to other areas and to other countries must, therefore, be done with care. Secondly, the ratings were made about hypothetical scenarios rather than real cases. We needed to use scenarios for the following reason. We examined how pieces of information were weighted, how they were combined, and how different groups of respondents differed in weighting and combining. One condition for examining the processes of weighting and combining, independently of other processes, is that each participant has the same information presented in the same way. Thirdly, multiple other factors may influence, of course, the judgments of lay people and professionals, even though, as stated in the introduction, previous work suggested that the factors we studied have wide generalizability.

Implications

As expected, lay people, whether Latin Americans (Chilean) or Western Europeans (French), manifest one of the same four qualitatively different personal positions on the appropriateness of a psychologist breaking confidentiality when patients are minors whose behavior puts their health in danger, specifically when they are taking illicit drugs (see also Hendrix, 1991). Among Chilean lay people, 46 % did not hold absolutists views; that is, they did not systematically condemn or approve breaking confidentiality (vs. 62% of the French). They were sensitive to the influence of situational factors on this difficult moral decision. Indeed, adding those who always supported the psychologist's decision (the Always acceptable cluster), a full 75% of the Chilean lay participants seemed to understand that when individual psychologists (or school counselors) break confidentiality in these cases, they are, above all, valuing their clients' well-being.

As a result, the public's trust in psychologists is unlikely to be undermined if, from time to time, individual psychologists decide that they must tell parents that their adolescent children are engaging in harmful behaviors. What parents would say if the adolescents were their own children requires further study.

References

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics, (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Colegio de Psicólogos de Chile (1999). Código de ética profesional. Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Colnerud, G., Hansson, B., Salling, O., & Tikkanen, T. (1996). Ethical dilemmas of psychologists: Finland and Sweden. International Journal of Psychology, 31, 476. [ Links ]

Dalen, K. (2006). To tell or not to tell. That is the question. Ethical dilemmas presented by Norwegian psychologists in telephone counseling. European Psychologist, 11, 236-243. [ Links ]

Donner, M. B., Van de Creek, L., Gonsiorek, J. C., & Fisher C. B. (2008). Balancing confidentiality: Protecting privacy and protecting the public. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 369-376. [ Links ]

Duncan, R. E., Williams, B. J., & Knowles, A. (2012). Breaching confidentiality with adolescent clients: A survey of Australian psychologists about the considerations that influence their decisions. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 19, 209-220. [ Links ]

Fisher, M. A. (2008). Protecting confidentiality rights: The need for an ethical practice model. American Psychologist, 63, 1-13. [ Links ]

Guedj, M., Muñoz Sastre, M. T., Mullet, E., & Sorum, P. C. (2006). Under what conditions is the breaking of confidentiality acceptable to lay people and health professionals? Journal of Medical Ethics, 32, 414-419. [ Links ]

Guedj, M., Muñoz Sastre, M. T., Mullet, E., & Sorum, P. C. (2009). Is it acceptable for a psychiatrist to break confidentiality to prevent spousal violence? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 32, 108-114 [ Links ]

Gustafson, K. E., & McNamara, J. R. (2004). Confidentiality with minor clients: Issues and guideline for therapists. In Bersoff, D. (2004) (Ed.) Ethical conflicts in psychology (pp. 190-194). Washington, DC: A.P.A. [ Links ]

Hendrix, D. H. (1991). Ethics and intrafamily confidentiality in counseling with children. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 13, 323-333. [ Links ]

Hofmans, J., & Mullet, E. (2013). Towards unveiling individual differences in different stages of information processing: A clustering-based approach. Quality and Quantity, 47, 555-564. [ Links ]

Isaacs, M. L., & Stone, C. (1999). School counselors and confidentiality: Factors affecting professional choices. Professional School Counseling, 2, 258-266. [ Links ]

Isaacs, M. L., & Stone, C. (2001). Confidentiality with minors: Mental health counselors' attitudes toward breaching or preserving confidentiality. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 23, 342-356. [ Links ]

Lindsay, G., & Colley, A. (1995). Ethical dilemmas of members of the Society. The Psychologist. October 1995. [ Links ]

Moyer, M. S., & Sullivan, J. R. (2008). Student risk-taking behaviors: When do school counselors break confidentiality? Professional School Counseling, 11, 236-245. [ Links ]

Moyer, M. S., Sullivan, J. R., & Growcock, D. (2012). When is it ethical to inform administrators about student risk-taking behaviors? Perceptions of school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 15, 98-109. [ Links ]

Munoz Sastre, M. T., Olivari, C., Sorum, P. C., & Mullet, E. (2014). Minors' and adults' views about confidentiality. Vulnerable Children & Youth Studies, 9, 97-103. [ Links ]

Olivari, C., Muñoz Sastre, M. T., Guedj, M., Sorum, P. C., & Mullet, E. (2011). Breaking patient confidentiality: Comparing Chilean and French viewpoints regarding the conditions of its acceptability. Universitas Psychologica: Pan American Journal of Psychology, 10, 13-26. [ Links ]

Ormrod, J., & Ambrose, L. (1999). Public perceptions about confidentiality in mental health service .Journal of Mental Health, 8, 413-421. [ Links ]

Pettifor, J., & Sawchuk, T. (2006). Psychologists' perceptions of ethically troubling incidents across international borders. International Journal of Psychology, 41, 216-225. [ Links ]

Pope, K. S., & Vetter, V. A. (1992). Ethical dilemmas encountered by members of the American Psychological Association: A national survey. American Psychologist, 47, 397-411. [ Links ]

Rae, W. A., Sullivan, J. R., Peña Razo, N., George, C. A., & Ramirez, E. (2002). Adolescent health risk behavior: When does pediatric psychologist break confidentiality? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 541-549. [ Links ]

Rae, W. A., Sullivan, J. R., Peña Razo, N., & Garcia de Alba, R. (2009). Breaking confidentiality to report adolescent risk-taking behavior by school psychologists. Ethics & Behavior, 19, 449-460. [ Links ]

Sinclair, C., & Pettifor, J. (1996). Ethical dilemmas of psychologists: Canada. International Journal of Psychology, 31 , 476. [ Links ]

Stone, C., & Isaacs, M. (2003). Confidentiality with minors: The need for policy to promote and protect. The Journal of Educational Research, 96, 140-150. [ Links ]

Sullivan, J. R., Ramírez, E., Rae, W. A., Peña Razo, N., & George, C. A. (2002). Factors contributing to breaking confidentiality with adolescent clients: A survey of pediatric psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 396-401. [ Links ]

Sullivan, J. R., & Moyer, M. S. (2008). Factors influencing the decision to break confidentiality with adolescent students: A survey of school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 6, 1-26. [ Links ]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Healthy People 2020 with understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office [ Links ]