Introduction

Often, headlines in the media shock the public with heartbreaking news about school violence. In Colombia, one such story is that of a 16-year-old teenager, Sergio Urrego, who committed suicide owing to the bullying he suffered at school because of his sexual preference and gender identity. The case was taken to the Constitutional Court, which issued a ruling that protected the rights of his family and ordered changes to the school coexistence manuals in order to prevent all kinds of harassment (Constitutional Court, 2015).

However, this issue is not just limited to educational centres; National newspapers such as El Tiempo expose acts of violence outside of schools, such as that of a minor under 12 years of age, whose hair was cut by two of her classmates with a knife. Later, the same aggressors stabbed the only student who tried to help the victim in the armpit (Perilla, 2015).

Despite the Court’s ruling, efforts to raise awareness have not been sufficient and bullying and other forms of violence continue to prevail in educational institutions and the surrounding neighbourhoods, not just in Colombia but in many other countries around the world as well. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Latin America and the Caribbean, young people are exposed to high levels of violence, particularly in schools (Soto and Trucco, 2015; Trucco and Inostroza, 2017). For example, according to the Argentine newspaper Infobae (2022), at least 20 % of students are victims of bullying in some form or another, which is a cause for concern for the community, in general, since it may result in other forms of violence and crime.

In addition, according to a study conducted in 2017 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, in Colombia, 7.6 % of students claimed to be exposed to some kind of physical abuse at their school on a daily basis (Perilla, 2015).

Based on the situation described above and the findings of the 2017 research project entitled “Edu- communication Strategy as an Intervention Tool for the Re-socialisation Processes of Adolescent Offenders Confined in the Buen Pastor Youth Training Centre (Cali)”, it was determined that the strategy of edu-communication effectively contributed to the re- socialisation of the adolescents in the training centre. Consequently, it was decided to utilise this strategy for the prevention of crime and school violence. Furthermore, it was recommended that this strategy be incorporated into the policies aimed at addressing these issues within the city of Cali (Behar et al., 2017). According to Del Campo et al. (2021), the different approaches used in prisons, oriented towards restricting the access and use of technologies by inmates in literacy programmes, trigger a delay or setback in the implementation of the edu-communication strategies. This also raises the need to train the prison educators in order to favour the critical use of technologies for the benefit of inmates.

Having direct access to communicative education strategies and technology can lead to two possible outcomes in the learning processes. On one hand, it can be advantageous due to the extensive interaction the user experiences with learning platforms. However, on the other hand, it can be detrimental due to the excessive presence of distractions or entertainment media on these platforms. This could be a barrier to the generation of clean and organic processes concerning the implementation of edu-communication strategies in Latin America (Lotero-Echeverri et al., 2019).

In order to assess the potential of edu-communication as an intervention tool in a setting outside of penal confinement, a research project was conducted by professors from the Faculty of Humanities and Arts at the Universidad Santiago de Cali (USC), the largest private higher education institution in southwestern Colombia. The study utilised a quasi-experimental design to investigate the feasibility of implementing the initial strategy. The objective was to raise awareness among a group of young people at risk regarding the importance of self-reflection and breaking free from the cycle of violence they encounter in their daily lives.

The project is based on the participatory action research (PAR) model, which uses the educational communication strategy as a learning and development mechanism through the construction of an independent pedagogy, the recognition of individual identity by those involved, and finally the deconstruction and reconstruction of discourses used by the individuals in question (Hasbún & Vásquez, 2021).

For sociologist Orlando Fals Borda, developer of this theory, which also fulfils methodological purposes, it is the cultural, political, and scientific experiences that enable the assumption of the role of a researcher and teacher in social action for knowledge and the transformation of reality. It is when the actors involved become the protagonists of this process, which allows them to elaborate proposals and solutions, that they intensify the participation process to achieve social transformation (Flores, 2021).

This is why it was necessary for the researchers to be involved in a specific population group, allowing first-hand analysis of their historical and structural conditions and promoting the active participation of the educational community and external agents focused on the prevention of crimes.

In a previous study, carried out for more than seven years, the Buen Pastor Youth Training Centre was intervened, with a population sample of 200 adolescents. A methodological primer is part of the result, in which the characteristics and methodology of a Sponsor Plan are described (Castillo & Behar, 2020). The application of this methodology is viable not only in young people in conflict with criminal law but also in other environments in which young people are vulnerable to violence, such as in schools.

Citing Zuluaga (2007), Cifuentes (2017) points out that “the school is losing its encyclopedic monopoly of knowledge” (p. 115), suggesting that the school is no longer seen as the sole place to access systematic and organized knowledge. With the advent of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), knowledge production now occurs even outside educational environments. Therefore, the context plays a crucial role in the teaching process for children and youth, as its integration in the classroom fosters suitable learning environments (Cifuentes, 2017).

Ordinarily, schools maintain adult-centric relationships, which can be broken through an intervention strategy and allow for the transformation of relationships between adult educators and young students, by means of their recognition as relevant social actors (Palma Salinas & Monsalves Ibarra, 2021). The implementation of this methodology fosters a more egalitarian form of communication, recognising that human development should not be solely focused on economic objectives.

It rejects the notion of individuals as passive recipients or mere beneficiaries of the intended well- being. Instead, it emphasises the central role of students as active participants, enabling the expansion of their opportunities across various aspects of society, such as the economy, knowledge, quality of life, freedom, personal security, community involvement, and fundamental rights. Rather than being a choice, this expansion should be regarded as a mandatory necessity (Tojeiro-Marrero & Guerra-Rubio, 2018).

Furthermore, the ongoing interaction between university students and schoolchildren, facilitated by the creation of communicative products, disrupts the conventional researcher-participant dynamic. Instead, it allows for a form of “performance autoethnography” that encourages self-reflection and explores the intricate connections between the self and society. This approach embraces the complexity of diverse identities and bodily experiences, encompassing multiple layers of self-expression (Lee, 2022).

Materials and methods

During the development of the project aimed at preventing delinquency and school violence, the Participatory Action Research (PAR) model was implemented at the Maricé Sinisterra Educational Institution in Cali, Colombia. This approach allowed for a direct understanding of the students’ reality and their immediate surroundings, where they face persistent exposure to violence and criminal activities.

For the qualitative analysis, a sample of 23 tenth-grade students from this institution was selected, ranging in age from 14 to 17. These students came from socioeconomic strata 1, 2, and 3, the lowest in Colombian society, and belong to a population where incidents of delinquency and violence have commonly occurred, such as muggings, hit-and-runs under the influence, and abuses. These issues have permeated the school environment, leading to constant acts of bullying, harassment, and evident physical, psychological, and verbal abuse, affecting the entire educational community.

To address this, a preventive edu-communicative strategy was designed1, replicating the “Plan Padrino”, (Godfather Plan) which had been successfully implemented for over 14 academic semesters with juvenile offenders at the Buen Pastor facility. In this plan, university students served as mentors for the adolescents, teaching communication tools such as audiovisual production, textual production, and radio production. Despite the success of the Plan Padrino, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 drastically affected in-person processes, preventing its continuation at the Juvenile Training Centre.

Given this new circumstance, the researchers conducted an exhaustive search to find a space where the Plan Padrino could be applied preventively. Consequently, the implementation of the edu- communicative strategy involved students enrolled in the course “Communication Strategies for Social Intervention” (Jordán, 2021) during semesters 2020B and 2021A. A total of 38 university students acted as mentors to the 23 adolescents in this study’s sample. Initially designed for physical spaces, the strategy had to be adapted to a virtual context due to the measures to counteract the spread of the virus. This adaptation posed a significant challenge in establishing relationships with the students and successfully implementing the strategy.

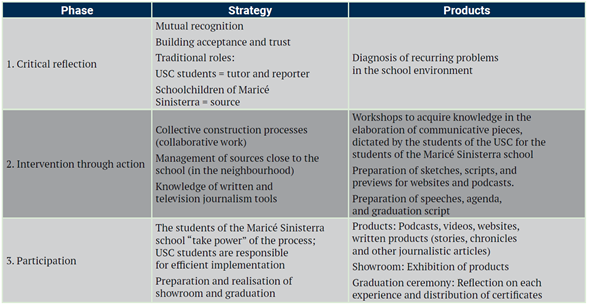

The strategy was developed in three phases: diagnosis, mutual recognition, and content creation, aimed at raising the students’ awareness of their reality, encouraging actions to break the cycle of violence and prevent its recurrence.

The developed phases consist of the following (see Table 1).

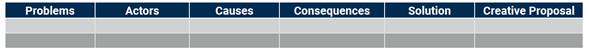

1. Diagnosis: This phase focuses on conducting a detailed observation of the participant, marking the point at which the researcher becomes involved in the reality being studied, interacts with the actors, and participates in the processes. This phase was carried out through problem diagnosis (see Table 2), during which the mentors and mentees identified and established the issues affecting their environment.

2. Participatory Research and Mutual Recognition: This phase employs methods rooted in collective work, the use of elements from popular culture, and historical recovery.

3. Participatory Action: Finally, this involves sharing the gathered information with the rest of the community through various methods presented by the researcher for data collection and socialisation (Corona-Aguilar & Barbarrusa, 2019).

Subsequently, a feedback exercise is conducted, thus concluding the participation phase. During this phase, adolescents from the Maricé Sinisterra Educational Institution apprehend the process, outlining guidelines for the quality implementation of these strategies.

Results

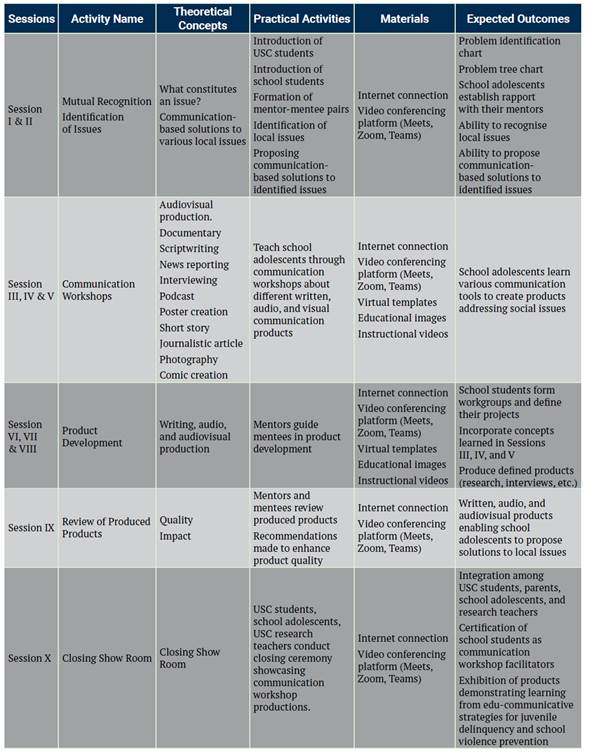

The results were obtained through in-depth interviews conducted with 4 school students and 4 university students who participated in the experience. The strategy’s design was also considered to verify compliance with the proposed objectives (see Table 3). According to the three phases executed, different outcomes were observed in each, as outlined below.

First phase: Diagnosis

In Cali, a city with 2 227 642 inhabitants, according to the 2018 census (DANE, 2019), there were 1 200 homicides in 2021, 13.2 % more than the figures of the previous year. This increase in the number of violence cases is similar to a certain extent to what was experienced during the National Strike, which had a strong presence in this city, since statistics show that it was in the months of May and June when the highest number of homicides occurred. In addition, in other Colombian capital cities, such as Bogotá, which has a population of approximately 8 million, 1 126 homicides have occurred, which indicates that the rate of violence in Cali continues to be alarming (El País, 2020). Further, the communes (popular neighbourhoods) where the most cases of violence occur are numbers 13, 14, and 15 with a record of 247 homicides (Tenorio & Gómez, 2020, p. 54).

Similarly, in 2021, acts of violence occurred in Commune 12, such as the one on February 7 in the El Rodeo neighbourhood, where the Maricé Sinisterra EI is located, leaving a 54-year-old person involved in micro- trafficking as a victim. On February 27, social intolerance due to conflicts between soccer team fan clubs left a child under 1 year of age as a victim due to a stray bullet (Muñoz & Martínez, 2021).

It is also important to mention the surroundings of Communes 12 and 132 of the city of Cali. These communes are located in the neighbouring areas to the school, where a significant number of cases of violence take place. An important amount of the student body belongs to those nearby communes, which means that the violence occurring in those locations indirectly involves the school population. An example of this is the increase of 56 % in the fines for contempt and disrespect for the police, along with the increase of 7 cases of homicide in the El Vergel neighbourhood (neighbour of Commune 12). Even during the isolation period due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an 8.8 % increase in theft (Muñoz & Martínez, 2021).

In relation to the above, the mayor’s office of Cali executed the 2020-2023 development plan, focused on the specific needs of each of the communes. For this, the problems of this community were identified. Although it is not oriented towards violence, it deals with highly relevant issues that directly impact social transformation, with the consideration of other variables. The problems in Commune 12, where the “Maricé Sinisterra” educational institution is located, include the following: lack of sports, recreational and cultural programmes, and equipment; lack of formal and non-formal training; lack of programmes to improve environmental conditions; low quality of education and infrastructure; and less social integration of the elderly (Cali Mayor’s Office, 2020).

Regarding the security reports of the city of Cali, in Commune 12, the number of homicides between 2019 and 2020 was 14, targeting people between the ages of 18 and 39. Of these, 11 were committed with a firearm and 3 with a sharp weapon. The rate of homicides increased from 1.7 % in the pre-isolation period to 2.3 % in the confinement stage. In addition, behaviours contrary to coexistence in this commune represent 4 % (Muñoz & Martínez, 2021). This, in comparison with the figures of the neighbouring communes, represents a lower value, which allows us to think about the feasibility of implementing the edu-communication strategy to help prevent the increase in violence cases.

Second phase: Mutual recognition

In the development of this initial phase, three aspects were fundamental: recognising oneself as interlocutor, the generation of acceptance and trust, and the execution of traditional roles (university student = tutor and reporter; students of the Maricé Sinisterra EI = apprentices and sources of the project).

In addition, at this point, the strategy called “Plan Padrino” was implemented, which facilitated the task of breaking the ice and generated mutual trust, since through this mechanism, each of the USC students oversaw one of the 23 tenth-grade students to guide them with regards to the journalism tools that were used. In the initial meetings, the young schoolchildren worked on the problems surrounding them, both in their school and community. The university students worked with them on a diagnostic format, which includes identifying problems, the actors involved, the possible causes, consequences, and solutions. In addition, the formulation of a creative proposal was requested that, based on communication, contributed to these solutions.

At this time, it was possible to analyse the different stages of their lives and the experiences in which school or neighbourhood violence was the protagonist, this being responsible for the subsequent acts such as bullying, harassment, among others. In addition, it was possible to gain insight into their vision of the future and the positive or negative decisions they could make upon completing basic secondary education.

Schoolchildren are the protagonists and university students are their guides

After breaking the ice in the meetings of the first phase, the collaborative work strengthened their relationship. It was possible to work on journalistic topics chosen by the students in the communication phase. Moreover, grammatical rules were reinforced, and two flow lines were established for journalistic work and different artistic expressions that the 23 students wanted to carry out, which include stories, videos, audios, and various digital products (see Table 3).

Accordingly, the second phase combined a series of key pedagogical actions, whose purpose was to stimulate young students in the processes of collective construction (collaborative work) of communication materials, making it necessary for the schoolchildren to learn about the management of sources within the institution and in their neighbourhood. In addition, knowledge regarding the use of written and audiovisual journalism tools as well as working on essential aspects such as collaborative work processes and management of sources within the Maricé Sinisterra EI were necessary. Thus, this provided students with knowledge about written and television journalism tools (Palma Salinas & Monsalves Ibarra, 2021).

Finally, with the development and culmination of the workshops of the second phase, the schoolchildren acquired the necessary media skills to produce the contents programmed within the strategy, which they proposed to solve the identified problem.

Third phase: Participatory Action - Production of printed content and graduation of adolescent workshop participants

Arriving at the final phase, the students had sufficient tools to appropriate the process and, thus, implement what they had learned in the workshops conducted.

The participation of the sponsors (university students) was important at this point, since they provided the schoolchildren with support in the creation of different products (podcasts, videos, stories, websites, etc.). With the help of these tools, the school students could recognise their position and assimilate the problems they have experienced and how they have been affected by them, leading them to perform the same acts on several occasions. It was evident that, through these edu-communicative products, they were willing to break this cycle of violence, as they developed an interest in addressing the issues in their environment and finding solutions for them.

As in the previous phases, the third phase had steps that were divided as follows:

The tenth-grade high school students apprehended the process and, with the guidance of their sponsors, managed to implement quality media production processes.

A showroom was held, an exhibition where the created products were presented to parents, teachers, and project members.

The culmination of the project was carried out with the graduation of the young students, who were certified by the USC.

The collective construction processes bore fruit through the following products: 6 infographics, 4 audiovisual materials, 3 audios, 2 relationship reports, 1 podcast with 4 chapters, and finally, 1 website named “Lecay, for youth and by youth”, where the reflections and actions of mentors and mentees regarding their issues are housed. There, five students identify themselves as members of a “Social Management Group composed of young people from the city of Cali with the aim of forming youth leaders to help contribute to social cohesion and mitigate violence” (Lecay, 2021).

Additionally, the researchers developed a documentary showcasing the experience throughout the process. For its production, interviews were conducted with 4 school students, 3 teachers, and 4 university students who were part of this experience, highlighting awareness-raising among the future graduates and their intention to distance themselves from the violence in their surroundings. Furthermore, they mentioned that, thanks to the edu- communicative strategy, they were motivated to build a new perspective on life.

It is important to mention that, as evidence of the experience, an event was held, called a showroom. This event included an invitation to the families of the schoolchildren, so that they would also become aware of the importance of transforming the reality of violence.

The purpose was to make them understand the need in assuming an active and collaborative attitude within the training process to support school students, who, thanks to the project, were able to get a glimpse of the possibility of accessing higher education or creating charitable projects that allow them to develop, in the future, as adults who provide a service to their community.

As mentioned, having first-hand experience of edu- communication generated a significant change in the school children in terms of their attitude towards life and a hope for progress. This experience also weakened the traces of violence they may have experienced and allowed them to create in their minds the goal of continuing their education even after the completion of secondary school studies.

Discussion

According to the results and the literature that corroborates them, it is possible to affirm that through the PAR model it is possible to achieve social transformation, wherein the actors participate with that objective, which emerged in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s, validating the effectiveness of this model. Its emergence was due to the need for an original science capable of explaining and taking charge of the problems that were experienced at that time, and it has been applied, especially in Latin America, for more than half a century.

The origin of PAR was mainly based on the criticism of the inability of theories from other cultures, such as European and North American, to fit into the Latin American context. This context was historically complex, in which society expressed itself, in the different countries of the region, through movements led by workers, peasants, middle classes and women, among others. This gave rise, as pointed out by some intellectuals, to the concern about the commitment of scientists “in the face of the demands of the reality of social change” (Palma Salinas & Monsalves Ibarra, 2021, p. 4).

In this model, it is essential to know and appreciate the role that knowledge plays, recognising everyone as human beings with valuable contributions from their individuality, so that by working together, bridges are built between scientific and popular knowledge to generate knowledge and free science capable of bringing about a change in the community (Palma Salinas & Monsalves Ibarra, 2021). In addition, the proposed methodology fosters the development of self-awareness and cultural understanding among schoolchildren through communication exchanges with university students. This mutually beneficial interaction promotes growth and learning for both groups involved (Brooks & Pitts, 2016).

Understanding that the educational communication strategy is a learning and development mechanism, the project is closely linked to this theory of the PAR model, which was carried out in educational institutions in order to implement it through previously established learning spaces. Furthermore, it was taken into account that the subjects benefited by the project are students, who can be approached through learning processes in order to avoid their participation in acts of violence or groups outside of the law. This provides children and young people an identity that allows them to understand the context in which they grow and how, based on their decisions, they can direct their lives away from violence. By utilising PAR and edu-communication approaches, educational institutions have the ability to create social systems that actively discourage violence, promote equality, and provide effective mechanisms for handling differences and conflicts in a constructive manner. This is achieved by placing emphasis on individuals’ perspectives and fostering positive relationships between individuals and groups (Broome & Collier, 2012).

The communicative part of the theory made it easier to recognise the realities of communities and individuals in adopting the appropriate measures, so that spaces of security and trust could be created through education and communication for the personal and social development of children and young people. In addition, Rivas et al. (2019) discuss how in Latin America, the intellectual production that involves these concepts is limited, which generates a spectrum of much greater scope over time, taking into account that the construction of spaces of security and trust is sought, which has a positive impact on learning processes or media literacy in young people and adults.

On the other hand, it is important to remember that the strategy was initially implemented in person at the Buen Pastor Youth Training Centre. However, while replicating the methodology developed in that experience, the researchers had to reflect on the validity of mobilising it to remote (virtual) spaces in the event of the closure of educational facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was then that they decided to undertake this quasi-experiment to corroborate its methodological efficacy in a different environment of non-contact, where the participants of the study enjoyed freedom while attending school from home. In these particular circumstances, the application of the strategy presented positive results and confirmed the perception regarding its effectiveness in contributing to social transformation, preventing crime and school violence, through edu-communicative strategies.

Finally, it is considered important to explore further implementation, either at the same educational centre or at another school with similar characteristics. This would allow for evaluating the results under in-person conditions and determining if the proposal achieves similar levels of effectiveness in both circumstances. This, in turn, would strengthen a methodology with significant academic utility.

Conclusion

The high rates of violence and juvenile delinquency in the El Rodeo neighbourhood, where the Maricé Sinisterra Educational Institution is located, underline the need for social intervention aimed at addressing and finding viable solutions to local issues. In this regard, it was observed that the edu-communicative strategy is effective in promoting reflection among adolescents about their vulnerabilities and the conditions that put them at risk of engaging in delinquent acts. This reflection has motivated them to set future goals and distance themselves from circumstances that may lead to violence.

Furthermore, it can be affirmed that the implementation of Participatory Action Research (IAP by its initials in Spanish) enabled active participation of the school students, who were able to identify local problems and propose communication-based solutions. This facilitated more meaningful and relevant learning as students became protagonists in their own learning process and social change. This approach contributed to students acquiring media skills, creating various communicative products such as podcasts, videos, stories, and a website, enhancing not only their media competencies but also allowing them to express and contribute to solving local issues.

Moreover, the strategy promoted a transformation in the typically adult-centric relationships found in schools, fostering more horizontal communication and recognising young people as significant social actors. This facilitated more comprehensive human development and greater social integration, empowering youth to continue their formal education and become agents of change in their communities.

Thus, edu-communication proves to be an effective vehicle for shaping new attitudes, contributing to the construction of a peaceful and democratic country. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate such edu- communicative strategies in educational environments, as they enable the proactive addressing of school violence and juvenile delinquency, generating new narratives around these issues that significantly affect Colombian society.

It is noteworthy that the primary task focused on equipping adolescents and future graduates in social communication with tools to interact effectively with society and understand the codes of behaviour and respect demanded in everyday, work, and academic life.

Therefore, it is essential to train both educators and students in media competencies and conflict resolution, ensuring that the strategy implementation is effective and responsive to the context’s needs.

This study also adds value to researchers in training, as through their professional exercise as evaluators and shapers of public opinion, they can adopt a sense of social responsibility along with a critical and ethical approach to communication practices and their responsibilities to society.

The results obtained align with findings from Sobrino et al. (2022), where the implementation of communicative techniques in teaching significantly improved participants’ competencies in such courses across Europe, leveraging new technologies and social media as primary supports in implementing edu- communicative strategies.

Lastly, despite the pandemic necessitating a shift to virtual or remote modalities, this circumstance facilitated the maintenance of interpersonal relationships among youth through technology, confirming that the project’s primary objective adapted effectively to the new reality in the country. Consequently, it was identified that the strategy can be successfully implemented in various settings, both in-person and virtual, yielding effective results. However, having a fully in-person setting in the future will be crucial to compare outcomes comprehensively and draw broader conclusions about its effectiveness, suggesting potential new lines or research objectives to complement the findings presented in this document.3