Colombian Journal of Anestesiology

ISSN 0120-3347

Case report

Peripartum cardiomyopathy - Rare, unknown and life-threatening*

Informe de caso sobre cardiomiopatia periparto: rara, desconocida y potencialmente fatal

Carlos Eduardo Laverde-Sábogála,**, Lina María Garnica-Rosasb, Néstor Correa-Gonzálezc

a MD, Intensive Care Unit - San Ignacio University Hospital, Bogotá, Colombia

b MD, Gynaecology Department, Pontificia Javeriana University, Bogotá, Colombia

c MD, Internal Medicine Department, Pontificia Javeriana University, Bogotá, Colombia

* Please cite this article as: Laverde-Sabogal CE, Garnica-Rosas LM, Correa-González N. Informe de caso sobre cardiomiopatia periparto: rara, desconocida y potencialmente fatal. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:63-68.

** Corresponding author at: Carrera 23 N° 118-32, Bogotá, Colombia.

E-mail address celaverde@husi.org.co (C.E. Laverde-Sabogal).

Article info

Article history: Received 22 April 2015 Accepted 27 August 2015 Available online 5 November 2015

Abstract

Objectives: To present a clinical case and to conduct a non-systematic review of the literature on peripartum cardiomyopathy, and to describe its incidence, aetiology and pathophysiology.

Material and methods: With the authorization of the Ethics Committee of our institution, we present the case of a patient of mestizo ethnic origin who developed asthenia, adynamia, lower limb asymmetrical pain and functional class deterioration during the post-partum period, and her management in the Intensive Care Unit and final outcome. The search of the literature was conducted in PubMed, Scielo and Bireme.

Results: Peripartum cardiomyopathy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The clinical course varies between progressive improvement, heart failure, transplant or death. Some national reports were found.

Conclusions: Peripartum cardiomyopathy affects a young and healthy population during a period of time ranging between the end of pregnancy and five months postpartum. The aetiology and pathogenesis are unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed: viral myocarditis, autoimmune and/or abnormal haemodynamic response to the pregnancy, genetic susceptibility, malnutrition, and apoptosis. The prognosis of recovery of left ventricular function (LVEF) depends on early detection within seven days of the onset of symptoms, an initial LVEF greater than 30%, and a left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVDD) smaller than 60 mm. Mortality is associated with parity greater than four, older age and black ethnc background (6.4 times higher than in Caucasians).

Keywords: Heart failure, Postpartum period, Pregnancy abdominal, Heart diseases, Hormones.

Resumen

Objetivos: Presentación de un caso clínico y revisión no sistemática de la literatura sobre cardiomiopatia periparto, describir su incidencia, etiología y fisiopatología.

Material y métodos: Con autorización del comité de Ética de nuestra institución, se presenta el caso de una paciente de origen étnico mestizo que durante su puerperio consulta por astenia, adinamia, asimetría en miembros inferiores acompañado de deterioro de clase funcional. Su posterior manejo en Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos y desenlace. La búsqueda bibliográfica se realizó en PubMed, Scielo y Bireme.

Resultados: La cardiomiopatia periparto es una enfermedad con una importante morbimortalidad. Su curso clínico varía entre una mejoría progresiva, falla cardiaca, trasplante o muerte. Encontramos algunos reportes a nivel nacional.

Conclusiones: La cardiomiopatia periparto afecta a una población joven y sana, desde el final del embarazo y hasta cinco meses postparto. Su etiología y patogénesis son desconocidas, las hipótesis propuestas son: la miocarditis viral, una respuesta autoinmune y/o hemodinámica anormal al embarazo, susceptibilidad genética, desnutrición, y la apoptosis. La recuperación de la fracciones de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo (FEVI) depende de: una detección temprana menor a siete días desde el inicio de los síntomas, la FEVI inicial mayor a 30% y diámetro ventricular izquierdo diastólico menor a 60 mm. La mortalidad está asociada con la paridad mayor de cuatro, la edad avanzada y origen étnico negro que es 6,4 veces mayor comparados con las caucásicas.

Palabras clave: Insuficiencia cardiaca, Periodo posparto, Embarazo abdominal, Cardiopatías Hormonas.

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) was first described in 1880 by Virchow and Porak, who found an association between heart failure and puerperium. In 1937, Gouley et al. found an idiopathic origin affecting young healthy women during the postpartum period. Its incidence, aetiology and pathogenesis are unknown. There are six case reports at a national level, but lacking ethnic information. Women of black race are the most affected in the world.1

Patient information

We present the case of a 23-year old female patient, G1P1C1V1A0, housewife, living in Umbita (Boyaca, Colombia), of mestizo ethnic origin. She weighs 45 kg and is 1.50 m tall. She has no history of disease or genetic disorders, and her surgical history was a caesarean section for her first pregnancy, at term, due to foetal macrosomia, with no complications.

Clinical findings

On postpartum day 30, the patient developed a picture characterized by asthenia, adynamia and cramp-type abdominal pain, with lower limb oedema, choluria and non-quantified fever, accompanied by functional class deterioration. Findings on physical examination included hepatomegaly, and marked

abdominal distension with progression to anasarca within an unspecified time period.

Diagnostic assessment

The urinalysis performed at the referring institution suggested urinary tract infection. Treatment with piperacillin/ tazobactam was initiated but was then escalated to vancomycin given the absence of clinical improvement. Later, the patient developed asymmetrical lower limb pain and venous Doppler revealed left deep vein thrombosis (DVT). After 15 days without clinical improvement, the patient was referred to our institution.

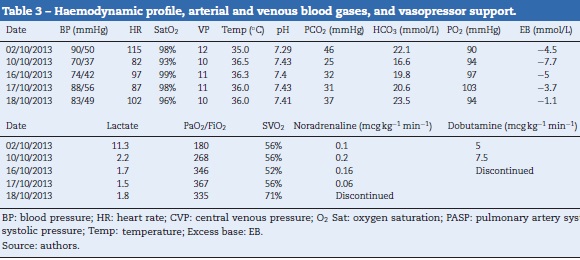

The patient presented to the emergency room with hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to pulmonary oedema, requiring invasive ventilation, vasconstriction with noradrenaline and intropic support with dobutamine. The patient was admitted to the ICU with jugular engorgement grade II at 45° and cardiac auscultation revealed an aortic murmur grade II and rales in both pulmonary fields. Additional findings included abdominal distension with hepatomegaly 3 cm below the coastal ridge, tenderness on palpation and anasarca, grade III oedema of the limbs, and asymmetrical left limb diameter. The neurological exam was normal. The patient developed multiple organ failure (see Table 1). Renal replacement therapy was initiated, and antibiotic coverage was scaled up to meropenem and linezolid due to suspected septic shock originating in the unirary tract, with no microbiological isolates.

Dengue, toxoplasmosis, HIV, viral hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr, blood borne parasites, parvovirus B19, Chagas disease, enterovirus and syphilis were all ruled out. Additionally, the immune profile ruled out systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome.

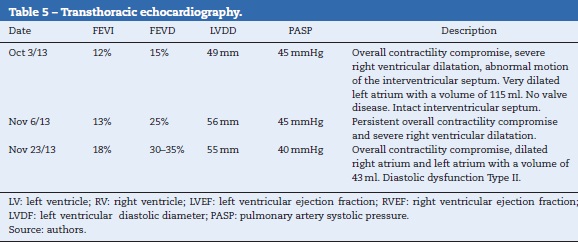

The initial transthoracic echocardiogram showed severe overall contractility disorder, with 12% left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and 15% right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), and a 49 mm end-diastolic left ventricular diameter (LVDD). Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was at 4349 pg/ml - the cut-off point for heart failure being greater than 500 pg/ml -leading to the diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Therapeutic intervention

The patient was infused levosimendan 12.5 mg (two doses) at a rate of 0.1mcgkg-1 min-1 over 24 h. Heart failure management was optimized by reducing ventricular response through the use of carvedilol, a cardioselective betablocker, together with enalapril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, and spironolactone, in order to block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis (neurohumoral block).

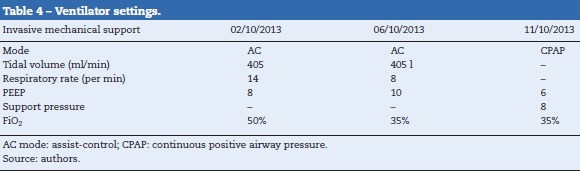

The patient had a favourable course with improvement of the haemodynamic and blood gas profiles, leading to the interruption of vasoactive and inotropic support. The BNP values dropped (see Tables 2 and 3). The invasive ventilation strategy was used successfully for 11 days (see Table 4). On ICU day 11, the patient recovered spontaneous diuresis and replacement therapy was discontinued. Finally, the patient was transferred to the ward for management by internal medicine for heart failure. The endomyocardial biopsy revealed oedema, with scarce and scattered interstitial lymphoid infiltrate, no evidence of thrombotic lesions or vasculitis, cardiomyocytes of varying sizes with large oval nuclei, round and irregular, no deposits of amyloid-like material, in a pattern considered non-specific. The patient is being worked up for cardiac transplant. Forty-five days after admission to the ICU, a new echocardiogram showed evidence of discrete recovery of left and right ventricular ejection fractions to 18% and 30-35%, respectively. However there was an increased left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVDD) (see Table 5). No adverse or unforeseen events occurred during the entire hospitalization period.

Discussion

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is idiopathic, characterized by heart failure with left ventricular dysfunction. It occurs within a time period of five months after the end of pregnancy, with no other cause to explain it.1,2

The true incidence or prevalence is unknown, and the range of distribution is wide, depending on the geographic area - 1:4000 live births in North America; 1:299 in Haiti; and 1:100 in Nigeria.3-5 Risk factors include older age, black race, prolonged use of tocolytics, obesity, exposure to psychoactive substances, and poverty.2 In their meta-analysis, Bello et al. found that the presence of pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, multiparity and twin pregnancy are high-risk factors.6-8 We found two national reports including 6 patients (see Table 6).9,10

The aetiology and pathogenesis of this disorder are unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed. These include viral myocarditis, an autoimmune or abnormal haemodynamic response to pregnancy, genetic susceptibility, malnutrition, and apoptosis. The opportunity to perform an endomyocardial biopsy, for medical and administrative reasons, implies a very wide range of microbiological isolates ranging from 0 to 100% of cases. The viral isolates that have been described include cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, Ebstein Barr, herpes simplex type 6, H1N1, influenza A/B. These may act as triggers to the development of an autoimmune response or simply constitute incidental findings given the similar incidence of isolates that has been found in patients with no peripartum cardiomyopathy.11-13. There is probably more than one trigger and it has been thought that foetal cells might create a form of microchimerism that could explain the response. High levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and C reactive protein have been found, making them mortality predictors.11 There is no clear knowledge about the role of micronutrients such as vitamins A, B12, C, betacarotene and selenium and, moreover, it varies by geographic region. Poverty could increase the susceptibility to infections.1

Diagnosis is made by exclusion and confirmed by echocardiography when left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is lower than 45%.2

The therapeutic strategy in PPCM is the same as in heart failure. The time of diagnosis, either prepartum or postpartum, is critical for determining the choice of medications. Beta-blockers may be used during pregnancy, although they are associated with low birth weight. During the postpartum period, it is appropriate to add angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors together with the use of diuretics. Additionally, digoxin may also be used.14,15

Bromocriptine is being used as adjunct to block the 16kDa receptor, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PPCM, in order to recover left ventricular function. The regimen proposed is the following: start with 2.5 mg every 12 h for 15 days and continue with the same dose for six weeks. Side effects are of thrombotic origin.16-19

Levosimendan did not modify mortality when compared with the control group. Likewise, there were no statistically significant differences with the survivors in the control group in terms of LVEF, pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) and the final left ventricular systolic/diastolic diameters. A dose of 0.1mcgkg-1 min-1 for 24h was used.20,21

Anticoagulation with low-molecular weight and unfractionated heparins is safe during pregnancy, when LVEF is less than 25%. Unfractionated heparin is preferred because of its short half-life and reversibility in an emergency. Warfarin is recommended during the postpartum period and emphasized in patients receiving bromocriptine.2,15

Goland et al. found that prognosis is tied to an early diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis of more than one week, associated with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) lower than or equal to 25% and non-Caucasian race, increases the possibility of developing major complications: ventricular cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, thromboembolism, refractory heart failure and the potential need for heart transplant, and death.22,23. Among the group of myocarditis, PPMC has a probability of LVEF recovery of more than 50% at 6 months in 80 90% of patients that meet two criteria: LVEF greater than 30% and end-diastolic left ventricular diameter (LVDD) under 60 mm, compared to 30-40% of cases with LVEF under 30% and LVCC greater than 60 mm.12,24 Pillarisetti et al. propose cardiodefribillator implantation (CDI) in the group of patients with left ventricular function under 30% and LVDD greater than 60 mm for primary prevention of sudden death.25

Mortality varies by geographic region, between 0% and 19% in the United States, and 14-16% in Brazil and Haiti. In the United States, the rate of heart transplant is between 6% and 11%. Factors associated with higher mortality include parity greater than four, older age, and black ethnic background, which is associated with 6.4 times higher mortality than in Caucasian women.2,5

Six reports were found in Colombia: one case at Valle University Hospital (Cali) and the remaining 5 as part of a retrospective study on heart disease in pregnancy conducted at Clínica El Prado (Medellín) between 2005 and 2009.9,10 In 2005, the population of women between 15 and 49 years of age in Medellín was 754,580 accounting for 30.19% of the total population of the city according to that year's census.26 Our patient of mestizo origin - not very studied worldwide - is similar in terms of age and first gestation to the national reports. The six cases reported at a national level occurred during pregnancy with a mean LVEF of 26% and LVDD of 57.6 mm, but there is no information regarding their ethnic background (see Table 6). Only one patient required levosimendan, none required heart transplant, and there were no deaths. Our patient, with a LVEF of 12% and LVDD of 49 mm diagnosed by exclusion more than 15 days after the initial visit required invasive ventilation, vasopressor, inotropic and inodilator (levosimendan) support on two occasions. Endomyocardial biopsy is delayed due to the clinical compromise, with a finding of a non-specific pattern.

Conclusions

Peripartum cardiomyopathy affects a young and healthy population during a period of time ranging between the end of pregnancy and five months postpartum. The aetiology and pathogenesis are unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed: viral myocarditis, autoimmune and/or abnormal haemodynamic response to the pregnancy, genetic susceptibility, malnutrition, and apoptosis. The prognosis of recovery of left ventricular function (LVEF) depends on early detection within seven days of the onset of symptoms, an initial LVEF greater than 30%, and a left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVDD) of less than 60 mm. Mortality is associated with parity greater than four, older age and black race (6.4 times higher than in Caucasians).

Patient's perspective

The patient and her family had positive feedback about the experience.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors did not receive sponsorship to undertake this article.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

References

1. Karaye KM, Henein MY. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a review article. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164:33-8. [ Links ]

2. Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, Hsia J, Oakley CM, Hosenpud JD, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283:1183-8. [ Links ]

3. Elkayam U. Clinical characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:659-70. [ Links ]

4. Cruz MO, Briller J, Hibbard JU. Update on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2010;37:283-303. [ Links ]

5. Gunderson EP, Croen LA, Chiang V, Yoshida CK, Walton D, Go AS. Epidemiology of peripartum cardiomyopathy: incidence, predictors, and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:583-91. [ Links ]

6. Bello N, Rendon IS, Arany Z. The relationship between pre-eclampsia and peripartum cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1715-23. [ Links ]

7. Kamiya CA, Kitakaze M, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Nakatani S, Murohara T, Tomoike H, et al. Different characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy between patients complicated with and without hypertensive disorders. Results from the Japanese Nationwide survey of peripartum cardiomyopathy. CircJ. 2011;75:1975-81. [ Links ]

8. Kao DP, Hsich E, Lindenfeld J. Characteristics, adverse events, and racial differences among delivering mothers with peripartum cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:409-16. [ Links ]

9. Monsalve G. Paciente embarazada con enfermedad cardiaca. Manejo periparto basado en la estratificacion de riesgo. Serie de casos 2005-2009. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2010;38:13. [ Links ]

10. Hernandez-Guzman A. Cardiomiopatia periparto: reporte de un caso y revision de la literatura. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2009;60:6. [ Links ]

11. Sarojini A, Sai Ravi Shanker A, Anitha M. Inflammatory markers-serum level of C-reactive protein. Tumor necrotic factor-a, and interleukin-6 as predictors of outcome for peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2013;63:234-9. [ Links ]

12. Fett JD, Markham DW. Discoveries in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:401-6. [ Links ]

13. Johnson-Coyle L, Jensen L, Sobey A. Foundation ACoC, Association AH. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: review and practice guidelines. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:89-98. [ Links ]

14. Ruys TP, Maggioni A, Johnson MR, Sliwa K, Tavazzi L, Schwerzmann M, et al. Cardiac medication during pregnancy, data from the ROPAC. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:124-8. [ Links ]

15. Stewart GC. Management of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2012;14:622-36. [ Links ]

16. Ballo P, Betti I, Mangialavori G, Chiodi L, Rapisardi G, Zuppiroli A. Peripartum cardiomyopathy presenting with predominant left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: efficacy of bromocriptine. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:1-6. [ Links ]

17. Sliwa K, Blauwet L, Tibazarwa K, Libhaber E, Smedema JP, Becker A, et al. Evaluatio of bromocriptine in the treatment of acute severe peripartum cardiomyopathy: a proof-of-concept pilot study. Circulation. 2010;121:1465-73. [ Links ]

18. Yamac H, Bultmann I, Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D. Prolactin: a new therapeutic target in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2010;96:1352-7. [ Links ]

19. Bello NA, Arany Z. Molecular mechanisms of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a vascular/hormonal hypothesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:499-504. [ Links ]

20. Biteker M, Duran NE, Kaya H, Gündüz S, Tanboga H, Gõkdeniz T, et al. Effect of levosimendan and predictors of recovery in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a randomized clinical trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:571-7. [ Links ]

21. Uriarte-Rodríguez A, Santana-Cabrera L, Sánchez-Palacios M. Levosimendan use in the emergency management of decompensated peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:94. [ Links ]

22. Goland S, Modi K, Bitar F, Janmohamed M, Mirocha JM, Czer LS, et al. Clinical profile and predictors of complications in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2009;15:645-50. [ Links ]

23. Fett JD. Earlier detection can help avoid many serious complications of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Future Cardiol. 2013;9:809-16. [ Links ]

24. Pieper PG. Predicting the future in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2013;99:295-6. [ Links ]

25 Pillarisetti J, Kondur A, Alani A, Reddy M, Vacek J, Weiner CP, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: predictors of recovery and current state of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt A):2831-9. [ Links ]

26. Departamento Administrativo Nacional [Sede web]. Bogotá; Departamento Administrativo Nacional; 2010 [citado Jun 15 2015]. Boletin Censo General Medellin (Antioquia) 2005 [6pantallas]. Disponibleen: http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/poblacion-ydemografia/censos. [ Links ]