Introduction

“You sound like a native. How long have you lived abroad?” “I can’t believe you learned English in Brazil. You barely have an accent!” Out of the several judgmental comments we might make with regards to our ways with words, the foregoing are still very expected appraisals Brazilian, and probably, Latin American, learners of English hear. These comments echo the everlasting stigma of non-native users of a language as deficient speakers (Canagarajah & Wurr, 2011). Going back to the time we were Brazilian English learners, we can now retrieve from our memories how such pervasive native speakerism was out there, doing its work, in our meaning-making processes on what the English language is, who speaks English well, where these voices come from and what we had to do in order to master this “l/anguish, anguish, a foreign anguish is english (sic)” (Philip, 2014, p. 32). It seemed quite simple: one of us dreamed about working as a babysitter in the USA whereas the other wished to visit Harry Potter’s homeland with a clear purpose in common: returning to Brazil after spending some time in the global north with a pure, flawless, crystal-clear English proficiency certified by the so-called owners of such language.

The commonalities that weave our English-language learning experiences seem to clash when we go one step further and see ourselves as English language teachers. This is because one of us, the older, was still trapped with native speakerism in her early professional experiences -constantly correcting students based on accurate and standard pronunciation. In contrast, the younger of us began her teaching career relying on a critical and deconstructive epistemology that questioned all hegemonic constructs such as purity, normativity, and universalisms around the field of English as a foreign language (EFL). Disturbance gained momentum later on when both of us started to address English language education from a decolonial perspective. As Brazilian, white, female, middle-class English researchers, each of us, in our own hermeneutic time, was able to gradually identify how colonial traces were heavily present in our identity formations as English learners and educators. Our self-awareness as products of coloniality due to our colonized history in relation to Portugal was suddenly and uncomfortably accompanied by self-awareness as producers of coloniality when learning, teaching, and researching the English language.

This article departs from our (self)-identification and (self)-interrogation of coloniality within the English language teaching (henceforth ELT) field as necessary steps toward the interruption of coloniality. Such a decision aligns with Souza (2019) and Souza e Duboc (2021) to whom the triad identify-interrogate-interrupt is fundamental to any decolonial exercise as further addressed. For this special volume, we will emphasize the concept and field of inquiry of English as a lingua franca. In this vein, we will argue that despite recent epistemological and ontological revisions, a critical and attentive reading of the ontologies and geopolitics of ELF knowledge production unveils a field strongly marked by European hegemony.

This paper is founded on extensive qualitative-interpretive research conducted by one of the authors (Rosa, 2021) under the influence of Ginzburg’s (1989) evidential paradigm as a methodological choice. Ginzburg associates this paradigm with the work of a detective when he states that the detective solving a crime relies “on the basis of evidence that is imperceptible to most people” (Ginzburg, 1989, pp. 97-98) and that we should examine “the most trivial details” (Ginzburg, 1989, p. 97) that end up being revealing. Inspired, then, by the evidential paradigm to analyze the concept and field of inquiry of ELF, we adopted this detective view and attitude as if we were approaching the lenses of a magnifying glass in search of details, marginal and secondary data, and usually discarded or ignored information. In other words, we were looking for revealing clues, evidence, and traces.

This article briefly outlines the ELF concept while identifying and interrogating where ELF voices come from and who can voice on ELF issues. In doing so, it presents part of the data resulting from an extensive ELF literature review as well as a documentary analysis of the International Conference of English as a Lingua Franca Programmes (Rosa, 2021). Findings show a complex weave of meanings marked by coloniality traces in which European viewpoints still function as la hybris del punto cero (Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel, 2007). Finally, the paper suggests a decolonial praxis in the reading of ELF -and of ourselves while reading ELF (Souza, 2011)- as a pre-condition for interrupting coloniality in English language educational contexts.

Theoretical-Geopolitical-Bodily Framework

This paper approaches ELF from the perspective of decoloniality. Before we theorize the decolonial concepts and ideas that are key to this analysis, a few words on ELF are necessary. The concept of ELF became widespread from 2000 on and is located at a time when human mobility, globalization, and new communication technologies pushed a plethora of new acronyms (Jordão, 2014). The latter attempted to take into account new functions and interactions in contemporary uses of English as a global language (Duboc, 2018). In this context, the seminal works of Jennifer Jenkins (2000, 2006, 2015) and Barbara Seidlhofer (1999, 2001, 2009), the founding mothers of ELF (Duboc & Siqueira, 2020), soon became the main reference in different countries in which ELF was defined as the function of English in communication between speakers of different first languages (Jenkins, 2000). In the words of Seidlhofer (1999), “non-native to non-native communication in English” (p. 239).

ELF studies have undergone different evolutionary phases over the last decades (Jenkins, 2015). An initial phase placed great emphasis on documentation, compilation, and codification under a still structuralist-oriented view of language. This is evident in Jenkins’ lingua franca core back in the 2000s that aimed at identifying the phonetic and phonological characteristics considered essential for intelligibility. While Jenkins, in the United Kingdom, was developing her studies on pronunciation features, Seidlhofer (2001), in Austria, was working on the description and codification of ELF through linguistic corpora to identify the regularities of English used in lingua franca contexts in her well-known Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE). Later on, ELF studies attempted to take into account notions such as accommodation and variability as a way to distance from the structuralist view of language. More recently, Jenkins envisioned the third phase of ELF which would encompass the complexities of translanguaging practices under what she coined English as a multilingua franca (Jenkins, 2015).

At first, we might read ELF evolutionary phases as positive moves that push English language conceptualizations away from structuralist constructs. However, we question the extent to which these different moves genuinely represent a paradigm shift, considering that some underlying notions are still present in global north elf production, as we will comment in the next section. This is so as ELF has been considered a polemic and polysemic term (Rosa, 2021), targeted from a love or hate logic among scholars within the field of English language studies. For this paper, we do not wish to insist on this endless theoretical buzz that has attempted to resolve what ELF is and what ELF is not. Rather, we would like to acknowledge what we have learned from Mignolo (2009b), considering not only what has been enunciated but also, and mainly, who enunciates and from where such enunciation departs. In other words, we seek to question who is/who is not sanctioned to speak about ELF, which voices are heard/silenced in ELF knowledge production and where these voices (do not) come from. This implies reading ELF beyond theory and discourse in the acknowledgment of how a geo-body-politics of knowledge (Mignolo, 2007) operates in the legitimacy/invisibility of voices. This implies, first and foremost, wearing decolonial lenses.

When we adopt decolonial thinking, we identify how colonial legacy denies, silences, or erases some subjectivities, knowledges, and worldviews whereas others are valued, accepted, and privileged. This aligns with Sousa Santos’ (2007) discussion on the abyssal lines that divide reality into two different universes: a visible one, i.e., this side of the line, and an invisible or even nonexistent one, i.e., the other side of the line. Contemporary decolonial studies stem from what came to be known as the Modernity/Coloniality school back in the 1990s and early 2000s. Such a school is based on the work of Latin-American authors such as Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel (2007), Mignolo (2009a, 2009b), Quijano (2005), Mignolo and Walsh (2018), Maldonado-Torres (2007) to name a few. Broadly speaking, the group began to question Eurocentric knowledge production in their claim on the need to enunciate about and from the perspective of global south epistemologies.

Coloniality creates a structural web of power relations that affects us and influences different dimensions of our existence, creating hierarchies of class, gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, epistemes, spirituality, aesthetics, pedagogies, and languages (Montoya et al., 2007). In contrast, decoloniality aims at deconstructing this heterarchical system of power, undoing, disobeying, and delinking from the colonial matrix so that other ways of thinking, feeling, believing, doing, and living can be possible (Mignolo & Walsh, 2018).

Although there is a diversity of decolonial projects, what they have in common is a colonial wound (Mignolo, 2009b), i.e., “the fact that regions and people around the world have been classified as underdeveloped economically and mentally” (p. 3). This author claims that decolonial thinking intends to unveil the epistemic silences of those who were racially undervalued, doing acts of epistemic disobedience. Along with epistemic disobedience, Mignolo contends that we delink ourselves from the traps of Modern Europe privilege through the acknowledgment of ourselves as knowledge producers. In Maldonado-Torres’s view (2007), decoloniality represents a change of perspective and attitude-a decolonial attitude in the author’s terms-which brings to the fore the perspective of those repeatedly suppressed and produced as nonexistent throughout history.

As this paper intends to question ELF knowledge production, we find it relevant to focus on the decolonial notion of geo-body-politics of knowledge. In questioning modern Western knowledge production, decoloniality ends up challenging the concepts of neutrality, objectivity, and detachment, imbued in the cartesian mode of knowing. As Garcés (2007) explains, such a mode creates the illusion that knowledge is delocalized and disembodied, something which decolonial thinkers refer to as ego-politics of knowledge. This notion relates to Castro-Gómez’s hybris del punto cero to refer to how Modern Europe and the cartesian subject have arrogantly placed themselves as the point of departure in relation to knowledge production. Grosfoguel’s words are worth bringing up to better apprehend the hybris del punto cero:

In the ego-politics of knowledge, the enunciation subject is erased, hidden, camouflaged in what the Colombian philosopher Santiago Castro-Gomez called the zero-point hybris (Castro-Gomez, 2005). It is a philosophy in which the epistemic subject does not have sexuality, gender, ethnicity, race, class, spirituality, language nor epistemic location in any power relation and produces the truth through an interior monolog, with no exterior influence. In other words, it is a deaf, faceless and weightless philosophy. The faceless subject floats through the sky guided by nothing and nobody (Grosfoguel, 2007, p. 64, our emphasis).

While the ego-politics of knowledge erases the ecologies of knowledge (Sousa Santos, 2007) -or pluriversality in Grosfoguel’s terms, the notion of geo-body-politics of knowledge aims at de-homogenizing and de-universalizing knowledge production by questioning the privileges of Western modes of knowing and being. Thus, from a decolonial perspective, we assume that knowledge is always located and embodied. This is because it always originates from a specific point of observation of a concrete embodied individual marked by their specific social-historical conditions, with no neutrality or objectivity (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007). What does acknowledging location and context mean? In practical terms, decoloniality relies on bringing back the body (Souza, 2019), that is, locating subjects in time, space, and history. In the words of Souza:

We have to bring the body back into this. How do we do this? By something very simple, a term we use in decolonial theory: the locus of enunciation, the space from which we speak. When we bring into account the space from which we speak, then we bring into account something which has been eliminated in academic discourse, which is the body. To speak from a space means you are speaking from a body located in space and time. When a body is located in space and time, a body has memory, a body has experience, a body has been exposed to history and the various conflicts of history. History has multiplicity, contradictions, etc. Bringing back the body into our pedagogies has come through in this project, not only in re-imagining but also in the use of creativity (pp. 10-11).

Hence, the decolonial lenses in ELF studies make us draw our attention to the subjects who enunciate about it and where they enunciate from. In doing so, we could not naively accept neutrality and objectivity in the voicing of our viewpoints. On the contrary, this paper encompasses located and embodied perspectives of two Brazilian, white, female researchers. This explains why the interrogation and identification of coloniality have to go hand in hand with self-critique and self-implication. In such wise, we embark on retrieving our own past experiences as former English language learners and understanding our own current English teaching practices. Likewise, we envision ourselves as English language researchers committed to the interruption of coloniality in language teaching and language knowledge production.

Decolonial Praxis in Action: Analyzing the Geo-Body-Politics of ELF Knowledge Production

Although we have asserted that this paper aims at analyzing the concept and field of inquiry of elf from a decolonial perspective, it devotes greater attention to the field of inquiry as we wish to explore the geo-body-politics of ELF knowledge production. In this vein, this section intends to briefly present a few words on conceptual aspects. It also tackles a more expanded discussion on where ELF knowledge is generated and who generates it. Thus, we seek to identify and interrogate coloniality. Finally, we listen to other voices enunciating on ELF in an attempt to interrupt coloniality.

Identifying and Interrogating Coloniality: Voices from the Global North

previously mentioned in the introduction. An extensive literature review conducted by Rosa (2021) demonstrates a complex and multiple weave of meanings in endless definitions and descriptions of ELF whose epistemological bases might differ considerably. According to Rosa (2021):

In some definitions, it is possible to infer a concept of objective knowledge, detached from the subject and with universalizing intentions, characteristic of modern/colonial knowledge production, and an idea of language as a system able to be described and codified with fixed meanings. Other theories adopt a concept of knowledge as local, situated and contextualized, and an idea of language as production and negotiation of meanings, that emerge in each singular discursive interaction (p. 113, own translation).

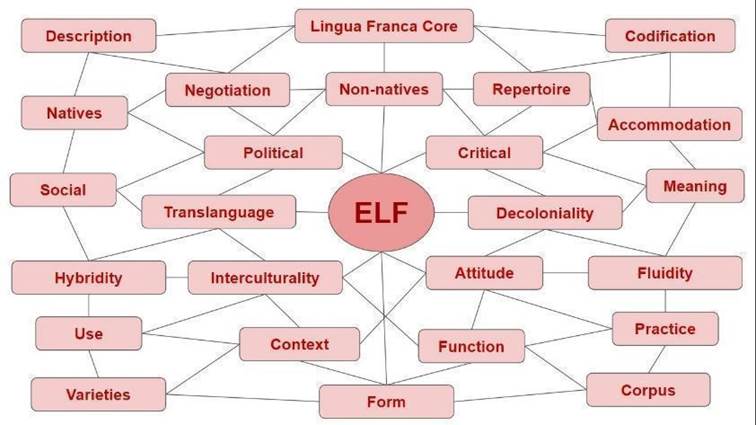

Such multiplicity in ELF understandings is depicted in Figure 1 which brings some of the key concepts usually present in ELF definitions in the last decades. What makes this multiplicity of understandings quite interesting and worth investigating is the fact that, despite Jenkins’ (2015) asseverations in relation to evolutionary phases within the field, ELF studies still carry a lot of ambiguities and contradictions. This is evidenced, for instance, in the coexistence of traditional concepts such as proficiency, native speaker, and even intelligibility with others that attempt to transcend them. In other words, despite all criticisms regarding the limitations of these concepts (Canagarajah & Wurr, 2011; Jordão, 2019; Firth & Wagner, 1997; Rajagopalan, 2010), they remain left untouched in ELF studies. Such a situation leads us to conclude that, in the end, certain ELF theorizations are still trapped within tradition despite their claims of innovation and change.

A very important aspect must be addressed at this point to prove our argument: language doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In this respect, Bakhtin’s (1981[1975]) words still resonate:

Discourse lives, as it were, beyond itself, in a living impulse [napravlennost’] toward the object; if we detach ourselves completely from this impulse all we have left is the naked corpse of the word, from which we can learn nothing at all about the social situation or the fate of a given word in life (p. 292, brackets in the original).

As we approach the ELF concept wearing decolonial lenses, we would like to add the missing element in Bakhtin’s theorization of language in the social fabric: the body. This is why a critical and attentive reading of the concept in question relies on taking into account who enunciates and from where they enunciate. Overlooking the geo-body-politics of ELF knowledge, we cannot excavate the origins of contradictions and ambiguities and might eventually fall into the traps of discursive appropriations. Put it simple, the fact that ELF scholars now use terms such as translanguage, interculturality, or critical does not necessarily mean they are withdrawing from a conventional onto-epistemological basis.

Canagarajah (2013) states that ELF has come closer to a practice-based perspective. However, he sees contradictions in the field by claiming that formal aspects, along with a concern with systematicity, logic, and legitimacy, prevail in ELF research up to this time, whereas negotiation strategies remain secondary. The same author criticizes Seidlhofer’s (2009) concept of community of practice and repertoire -which would supposedly represent a shift between ELF phases 1 and 2- by claiming that these concepts also depart from predictability and stability instead of performativity and negotiation.

In line with Canagarajah’s critiques, we propose to investigate the ELF field of inquiry with a decolonial magnifying glass in the search for traces that deconstruct such ambiguities. For this investigation, Rosa (2021) has proposed to turn the attention to one of the most important conferences about ELF, the International Conference of English as a Lingua Franca. This event used to take place once a year at universities in different countries gathering scholars from different parts of the world. From 2008 to 2020, the conference was hosted by the following countries respectively: Finland, United Kingdom, Austria, China, Turkey, Italy, Greece, China, Spain, Finland, United Kingdom, Colombia and Taiwan. Figure 2 visually displays the geopolitical choices:

Figure 2 shows a European predominance in ELF knowledge production and distribution whereas South America, for example, has hosted the event only once.

Source:Rosa (2021, p. 73).

Figure 2 International Conference of English as a Lingua Franca Host Countries

Behind such geographical distribution lies the colonial matrix of power (Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2005) and knowledge (Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel, 2007). Thus, Modern Europe becomes the geographical and epistemic point of departure - la hybris del punto cero - in its endeavor to spread knowledge, progress, science, and development to other parts of the globe.

We could wonder about the extent to which Europe is placed as the zero point as the map shows that ELF conferences did occur in countries other than European. Zooming in once again with our magnifying glass, more traces pop up in the unveiling of the colonial driving forces within the ELF field of inquiry. This is what happens when we consider the keynote speakers in the last ELF conferences. During her investigation, Rosa (2021) found out that most invited speakers come from European countries such as the United Kingdom and Austria, where the first studies about elf were developed, as shown in Figure 3.

The data were based on seven out of the 13 editions held of the conference, ranging from the 7th to the 13th editions, from which only 4 are still available online (see ELF7, 2014; ELF11, 2018; ELF12, 2019; ELF13, 2022). The information collected included keynote speakers, colloquium chairs, and plenary speakers. Based on the data above and inspired by the decolonial exercise of interrogating who produces knowledge and where it is produced, it is possible to understand how coloniality pervades this field of inquiry, as previously mentioned. Along with the coloniality of power and knowledge behind the geopolitics of ELF knowledge, this map brings to the fore the coloniality of being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007) as it considers the agents of such a field. Coloniality of being is intrinsically related to Quijano’s (2005) discussion on how Eurocentric capitalism engendered by Modernity was supported by coloniality of power that ended up justifying an arbitrary social classification in which the concept of race served the purposes of exploitation, domination, and exploration. Quijano (2007) expands this idea, claiming that: “Eurocentric coloniality/modernity is a conception of humanity, according to which the world population is differentiated into inferior and superior, irrational and rational, primitive and civilized, traditional and modern” (p. 95, own translation).

This goes hand in hand with Mignolo’s (2009a)colonial difference when he explains that:

The colonial difference operates by converting differences into values and establishing a hierarchy of human beings ontologically and epistemically. Ontologically, it is assumed that there are inferior human beings. Epistemically, it is assumed that inferior human beings are rational and aesthetically deficient (p. 46, our emphasis).

The notion of colonial difference helps us approach the choice of the keynote speakers in the last ELF conferences. An inferiority attributed long ago to indigenous and black people, who have been historically placed at a locus of deficiency, somehow reverberates within the ELT field, including ELF. Here the target turns to be the non-native speaker, mainly those located at the other side of the abyssal line.

In addition, Veronelli’s (2016) theorizations on the strong relationship between language and racialization and how Eurocentric philosophy, ideology, and politics have dictated the norms are fundamental to support the argument raised here. Following this idea, we are probably considered by them as simple communicators for supposedly lacking the ability to produce qualified, worth-to-be-heard-and-read knowledge on language issues.

In this respect, it is important to explain what we mean by global north in this subsection. According to Sousa Santos (2016), north and south are not understood here as geographical concepts but as symbolic, metaphorical terms representing social inequalities, exclusion, and oppression. Situations like these are caused by capitalism and colonialism, but also by the resistance to this system. In turn, the south is present in the geographical north through those historically marginalized, excluded, and silenced. Therefore, the south and north must be understood in relative terms. Similarly, geographical and epistemological loci must also be understood in the same terms. This is because not always those located in the geographical north take on a hegemonic epistemological locus while those located in the geographical south do not necessarily assume a resistance locus.

Following a similar line of thought, when we point to the European hegemony in ELF knowledge production, we must also talk about Europe in relative terms, in a way we distinguish Europes within Europe with their north and south. We refer to countries such as Greece, Italy, Turkey, Spain, and Portugal as occupying a marginalized position concerning countries such as the United Kingdom, for example. The following section briefly brings these voices to the fore.

Interrupting Coloniality: Voices from Other Europes

There is a very promising ELF knowledge production in Southern European countries which is now becoming more and more visible. This is the case of Cavalheiro and Guerra in Portugal, Sifakis in Greece, Bayyurt in Turkey, and Lopriori and Vettorel in Italy. The common ground among these scholars in relation to ELF theory seems to be a larger concern with the pedagogical implications of the field which, in turn, magnify educational praxis. That is, these scholars have engaged in investigations on how the ELF theoretical perspective can reflect on English language teaching contexts, looking at classroom practices, coursebooks, and teacher education. This might be a very positive move as the first ELF studies back in the 2000s did not seem to approach educational issues.

Cavalheiro (2020), for instance, articulates ELF to the possibility of promoting intercultural exchanges and dialogues and sees the English language classroom as a space for integrating migrant students. She analyzes classroom activities from Portuguese schools with migrant students. The first activity she mentions is related to characters from different countries represented as English language speakers, such as Indians and Chineses, with different accents characteristic of these varieties are generated by an online app of avatar creation. Another activity includes different cultural perspectives about Easter, which leads to a concept of ELF articulated to the notion of interculturality. Finally, the last activity is an interaction between students from different countries in which they used different strategies to communicate with each other. In her analysis of these school practices, Cavalheiro (2020) highlights the ideas of identity, emergence, and negotiation associated to ELF.

Guerra et al. (2020) reports a comparative study about English language teaching materials developed by researchers from Portugal, such as Guerra himself, Pereira, and Cavalheiro, and from Turkey, such as Kurt, Oztekin, Sonmez-Candan, and Bayyurt. They aimed at analyzing if different uses of English in international communication are present in materials from these two countries. They conclude that hegemonic varieties still prevail and international uses of English and an ELF-based perspective are still absent in teaching materials.

In line with the above authors, Sifakis (2017), mentions the influence of the ELF perspective on English language teaching and undertakes extensive work on teacher education in order to develop an ELF awareness-based teacher education program. He supports an integration between ELF and EFL, so teacher education should develop what he calls ELF awareness. This in turn is, defined as

the process of engaging with ELF research and developing one’s own understanding of the ways in which it can be integrated in one’s classroom context, through a continuous process of critical reflection, design, implementation and evaluation of instructional activities that reflect and localize one’s interpretation of the ELF construct. (Sifakis; Bayyurt, 2018, p. 459 apud Sifakis, 2019, pp. 290-291)

According to the author, ELF awareness means to acknowledge the debate and the research about ELF in order to put into practice what is possible, depending on each context. He emphasizes the idea of attitude among those involved in the teaching process: teachers, curriculum and coursebook designers, teacher educator, examiners, and so on.

Lopriore and Vettorel (2015) analyze the influence of World Englishes and ELF paradigms on Italian coursebooks for English teaching and how these perspectives echo in the English classroom. By World Englishes (WE), we refer to the field of inquiry developed for studying and validating the different varieties of English around the world especially resulting from the processes of colonization. For further details, please see Canagarajah (2013). Lopriore and Vettorel (2015) bring up the notion of agency, intercultural awareness, meaning-making, communicative and negotiation strategies to the discussion of we and ELF perspectives.

They notice an absence of non-native speakers represented as legitimate speakers of English and also of activities aimed at developing communicative strategies, considered as essential for English language teaching in WE and ELF contexts. However, they identify a positive aspect regarding activities that develop intercultural awareness, including aspects of different countries and lingua-cultural contexts, and also promoting students’ awareness about their own culture.

Finally, the authors stress that adopting a WE or an ELF perspective means to go beyond a monolithic view of language and culture, which implies a change in perspective and “one that ‘would enable each learner’s and speaker’s English to reflect on his or her own sociolinguistic reality, rather than that of a usually distant native speaker’ (Jenkins, 2006a, p. 173) and to each local context of learning and use (Lopriore; Vettorel, 2015, p. 17).

All in all, the field of ELF studies has fertile ground in countries other than hegemonic Europe. Would the same phenomenon occur in the global south? We will devote a few words to this in the following subsection, with an emphasis on ELT Brazilian scholarship.

Interrupting Coloniality: Brazil Speaks Back

ELT studies in Latin American countries are now becoming renowned. In this subsection, we will emphasize the ELF production in Brazil for two main reasons: word limit and locus of enunciation. In this vein, although ELF is already established as a solid field of inquiry in the international scenario, Brazilian research on this perspective is recent. Bordini and Gimenez (2014) recognize a significant increase in the number of studies on ELF between 2008 and 2011 in Brazil. Since then, more works on the topic have been published (see, for example, Gimenez et al., 2015; Siqueira, 2015, 2018; Jordão & Marques, 2018; Duboc, 2018; Jordão, 2019; Duboc & Siqueira, 2020). We acknowledge that in recent years more theses, dissertations, and academic papers on ELF have flourished in Brazil and could not be brought to the fore. An updated literature review is necessary.

In recent studies, Brazilian scholars like Duboc and Siqueira (2020) have based their reflections about ELF on decolonial thinking. Departing from the decolonial ideas of epistemic pluralism and copresence of epistemologies, Duboc and Siqueira (2020) question the European predominance in ELF studies so that research produced in the global south becomes visible. This is based on echoing Sousa Santos’ (2007) concept of abyssal thinking, i.e., when knowledge produced on the other side of the line is invisible. The authors highlight the Brazilian production of ELF as a political act of resistance, which Duboc (2018) calls ELF feito no Brasil. Drawing on critical literacy studies, critical applied linguistics, Freirean critical pedagogy, and decoloniality, they articulate ELF to the critical and political nature of language, power relations, and the connection between subject, identity, culture, coloniality, and translanguage. When theorizing about ELF, the Brazilian scholars above mentioned bring these issues to the fore to think about the concept of ELF and how this perspective can relate to our local contexts and influence teaching practices.

In line with this, Jordão (2019) posits the notions of border thinking and delinking as a way to distance ourselves from monolingual perspectives in theories of acquisition. Hence, we can approach a view of language as a social practice and translanguage, i.e., conceived as a social construction in a never-ending process recreated in each enunciation act. The author highlights the modern/western influence on our language teaching methods and strategies, which results in varied epistemological violence. To overcome this violence, she asserts that it is necessary to decolonize our minds, delinking ourselves from these perspectives.

By the same token, Siqueira (2015) claims that ELF is a de-territorialized use of language, adapted to the needs of those who use it. This would entail making deep changes in language teaching and teacher education and displacing the uses and the users of non-hegemonic varieties of the language from marginalized or even invisible places. In doing so, the author deems it crucial to elicit an epistemic break with western pedagogic traditions from the global north. Thus, he advocates for a critical intercultural language teacher education that deals with questions of identity, power, racial conflicts, social change, and global mobility. But this break can only happen with a change of attitude when we start distancing ourselves from utilitarian perspectives. Similarly, this is achievable when we remove ourselves from the subaltern position of non-native speakers of the language where we were placed by colonial centers of power.

Similarly, Gimenez et al. (2015) believe that ELF-based teaching can develop a critical awareness in learners, focusing on global interest issues that go beyond Madonna and mainstream topics. In this train of thought, they affirm that didactic resources based on ELF should include “examples of many different types of interaction between non-native speakers, respect local varieties of English, develop tolerance for differences and promote cultural diversity” (Gimenez et al., 2015, p. 226). According to them, the greatest challenge in promoting ELF education is reconceptualizing ideas such as the native speaker model, intercultural awareness, and changes regarding how we think about teaching and language, methodologies and materials, beliefs, and attitudes. They also articulate ELF to the concept of interculturality. In their view, intercultural awareness is necessary to deal with different ways to produce meanings and possible cultural misunderstandings. This contests the promotion of a monolithic view of culture and associates the use of the language with specific cultures and countries.

Jordão & Marques (2018), in turn, see language teaching and learning as spaces for negotiation of meanings, and recognizing contradictions and conflicts as important aspects in this process. Based on a Foucauldian perspective, the authors understand language in its power relations, i.e., whereas some meanings are legitimate, others are excluded. They reinforce the need to get rid of old habits that persist in the English language field and teacher education. When looking at materials, they reckon it important to observe how the underlying concept of language allows the production of meanings. For them, it is also vital to analyze the extent to which the conceptions of language reinforce normative views of what is considered valid, especially through what is omitted and excluded. Lastly, the role of the teacher should be about mediating the relation between learner and knowledge, and not communicating neutrally an established reality. The authors affirm that maybe English teachers have never actually taught the standard language, but “transformed, translated, distorted, modified Englishes or, as a teacher once told us, they may have been teaching, in fact, ‘the English they can’”. (Jordão & Marques, 2018, p. 65, emphasis in the original).

Finally, Duboc (2018) understands that ELF-based teaching implies weakening universalizing notions such as error, imitation, and deficiency to give rise to the ideas of variation, accommodation, and difference. For this author, ELF can serve as the path for critical agency seen as pivotal in a global and digital world, where different ways of producing meanings are created. Thus, she articulates ELF to her idea of curricular attitude, in which teachers could act between the cracks and make critical interventions to promote change in classroom fertile moments to expand perspectives.

When we compare different Brazilian voices on ELF perspectives, it is possible to state that in our local elf appropriation resides resignification, what Duboc (2018) has been referring to as ELF feito no Brasil. These theories link the concept of ELF with aspects that were not initially considered in global north studies, especially those related to criticality, politicity, and agency along with their concern with power relations in the use of language.

It is interesting to observe that decolonizing knowledge is descending from the zero point and making evident the place from where knowledge is produced as suggested by Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel, (2007). So does the term ELF feito no Brasil: far from any desire to take Brazil as a homogeneous country, it simply delimits a perspective, a point of view, a specific point of observation, and a specific locus of enunciation. One whose localized and embodied knowledge is evident when we acknowledge geo-body-politics of knowledge in opposition to an ego-politics of knowledge.

Conclusion

This paper aimed at analyzing ELF knowledge production from the perspective of decoloniality. Drawing heavily from the work of Rosa (2021), we conclude that the ELF field of inquiry is marked by tensions, ambiguities, and contradictions in which updated and innovative ideas coexist with conventional language constructs. The paper claims that, along with understanding all the multiple meanings of ELF in such a complex semantic web, the need arises to identify and interrogate the very privileged and/or marginalized status of ELF knowledge production worldwide as a pre-condition to interrupt hegemony. Founded on the notion of geo-body-politics of knowledge, decolonial analysis of the last international ELF conferences with regards to its hosting countries and its keynote speakers has shown that Northern Europe is still placed as the zero point concerning ELF knowledge production. To put it differently, this study (Rosa, 2021) demonstrates that coloniality traces still operate in a field deemed disruptive to mainstream TESOL theories and practices.

Bearing in mind that ELF knowledge production does take place in different parts of the world -as brought in the last two subsections- we wonder if the knowledge from the margins is taken as legitimate and valued by those from the center. In our view, such production might not be acknowledged not because of the knowledge value itself, but because of the values assigned to these marginalized subjects. Now, how does one begin to interrupt such logic?

Duboc and Siqueira’s (2020) questions, from which we have selected some, might be useful for this exercise towards the interruption of coloniality:

[…] To what extent do mainstream European ELF researchers involve themselves in truly horizontal and collaborative research work as a way to tackle the problem of the zero point hybris? […] How much of ELF’S main literature circulating in the academic realm is representative of multiple and dissent voices ranging different loci of enunciation? […] Are global south ELF scholars aware of the colonial matrix of power in knowledge production? If so, to what extent do they truly wish to epistemically and politically de-link? […] To what extent are global south ELF researchers truly committed to disposing of their historical self-marginalization with regards to their own command of English and research products? […] To what extent are global south ELF researchers engaged in disobeying, disrupting, and transforming the status of ELF research and practice? (p. 240).

We would like to add a few more questions to the discussion based on Rosa (2021): Is the use of English by speakers from different parts of the world legitimate and valued just because such validation came from global north voices? Is the English language still a gatekeeper, controlling and filtering knowledge production about ELF despite current theory favoring fluidity and hybridity? If some voices speak louder than others, would not certain meanings be consequently more widespread than others? We do not intend to answer these questions but to boost reflection on how coloniality of power, being, and knowledge permeate these issues.

The endeavor to write about coloniality cannot be detached from self-critique and self-implication. We have tried to be attentive to see coloniality pertaining to others but also to ourselves in a decolonial exercise towards (self)identification and (self)interrogation of coloniality following Souza and Duboc’s (2021) thoughts on the matter:

One of the initial risks is to see coloniality as pertaining to others and not to the self. This can occur if location is not taken into account. If coloniality, as we have just seen, refers to a complex and interconnected set of hierarchical relations stemming from the colonial difference, it is often difficult to identify on which side of the colonial difference, we are located as critical analysts. Together with the step of interrogation, identifying coloniality needs to depart from an awareness of one’s location, or one’s locus of enunciation. On which side of colonial difference is it located? Is it on the side that takes for granted that it, and its knowledges are the punto cero and all other to it is racialized as inferior? Or is one analyzing from a locus of enunciation that has been othered, negated, invisibilized and racialized? (p. 881).

To conclude, both of us were able to see coloniality traces here and there in our own life experiences as English language learners/users, educators, and researchers. Back in time, we see coloniality in our most-secret desires to live abroad, learn real and good English and be positively praised in our English interactions. Is it all solved now that we are aware of how colonial difference operates towards privileging some while marginalizing others? We do not think so. While we are ending this text, we realize how coloniality is suspended in the air.

When we submitted our article for this special volume, we were aware that we did have the option to write in Portuguese, our first language -and such editorial openness is, itself, an urgent and most-welcome decolonial attitude in the time of still prevailing English ideology within academic knowledge production. Yet, we picked English, founded on the premise that notions like foreignness and ownership have long been problematized within critical applied linguistics.

Despite all this awareness, we experienced this co-authored work amid distinct feelings: suffering (for picking words), guilt (for correcting one another), shame (for exposing our weaknesses), but also empowerment (for the opportunity to be voiced in this special volume), gratitude (for all the learning built throughout this writing process), and joy (for this cherished encounter between us in such co-authorship). Once again, we found ourselves products and producers of coloniality. But once again, we found ourselves reasserting the willingness to engage in such the urgent task of ELT decolonization.