Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Administración

Print version ISSN 0120-3592

Cuad. Adm. vol.21 no.37 Bogotá Sep./Dec. 2008

* Institutional research in progress for Universidad del Rosario, which is now exploring other university cases, in order to do a comparative study. This research, funded by Universidad del Rosario, started in 2006 and is expected to end in 2009. The first part of it will lead to a paper for a DBA in Higher Education Management from University of Bath in Bath,

** Bachelor's Degree in Economics with a Specialization in Finance from Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, Colombia, 2004; Master's Degree in Economics, London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom, 1998; Candidate for PhD in Business Administration in Higher Education Management, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingfom. Professor at the Faculty of Economics and member of the Grupo de Investigaciones de la Facultad de Economía de la Universidad del Rosario. Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: jrestrep@gmail.com.

ABSTRACT

Given the new trends in the higher education system in

Key words: Academic credits, flexibility, university management, higher education, flexibility of provision.

RESUMEN

Dadas las nuevas tendencias del sistema de educación superior en Colombia, este trabajo plantea la pregunta ¿cómo puede la introducción de sistemas de créditos transformar la gestión de una universidad? Para contestarla este trabajo presenta el caso de la Universidad del Rosario, una de las más tradicionales en Colombia, y explica cómo transformó su entorno institucional para implementar dicho sistema años antes de la existencia del requerimiento legal de los sistemas de créditos. En el trabajo se revisa la literatura no sistemática sobre el tema y se presenta el concepto sistemas de créditos; luego se propone un modelo de cuatro categorías que sistematiza el cambio en la gestión: (i) gobernación y estructura, (ii) cultura/valores e identidad institucional, (iii) prácticas y técnicas gerenciales y (iv) relación con el ambiente (interno y externo). El trabajo también considera las particularidades culturales e institucionales que pueden afectar y distorsionar el impacto esperado de la introducción de sistemas de créditos, y la importancia de la dinámica del proceso cuando se trata este tema.

Palabras clave: créditos académicos, flexibilidad, gestión universitaria, educación superior, fl exibilidad de provisión.

RESUMO

Com as novas tendências do sistema da educação superior na Colômbia, este trabalho expõe a pergunta de como pode a introdução de sistemas de crédito transformar a gestão de uma universidade. Para responder esta pergunta, este trabalho apresenta o caso da Universidad del Rosario, uma das mais tradicionais na Colômbia, e explica como transformou seu entorno institucional para implementar dito sistema, anos antes da existência do requerimento legal dos sistemas de crédito. No trabalho revisa-se a literatura na sistemática sobre o tema e apresenta-se o conceito de sistemas de crédito: logo propõe-se um modelo de quatro categorias que sistematiza o câmbio na gestão: (i) governo e estrutura, (ii) cultura/valores e identidade institucional, (iii) práticas e técnicas gerenciais, e (iv) relação com o ambiente (interno e externo). O trabalho também considera as particularidades culturais e institucionais que podem afetar e distorcer o impacto esperado da introdução de sistemas de créditos, e a importância da dinâmica do processo quando se trata deste tema.

Palavras chave: créditos acadêmicos, flexibilidade, gestão universitária, educação superior, flexibilidade de provisão.

Introduction

Without a doubt, the world of higher education is experiencing a scenario of change. Deem (2001), Clark (1998), Gibbons et al. (1994), Marginson (2000), Marginson and Considine (2000), Slaughter and Leslie (1999), and Slaughter and Rhoades (2004), among others, have identified recent trends in higher education, such as globalisation, internationalisation, new managerialism, entrepreneurialism, marketisation, consumerism, enterprise university, and academic capitalism.

One of the changes introduced in this new scenario is curriculum flexibility and the credit system is one of the main tools for developing that process. Credits and flexibility of provision are usually explained in the literature on the topic as an example or a consequence of a particular trend in higher education. The change towards flexibility of provision and the credit implementation has particular importance in Latin American higher education systems and especially in the case of Colombia, acknowledged in that region as one of the countries which has advanced most in academic credit implementation (Restrepo, 2008).

Since 2002 the Colombian Ministry of Education1 has been concerned with the need to implement new strategies to adopt flexible forms in higher education using, for example, academic credits, education divided into cycles, and other tools. Recently, the outside pressure to implement credit systems and flexibility of provision may be associated with the Latin America Tuning Project2 and CENEVAL Project 6 x 43, both of which are attempting to bring Latin America and Colombia the implementation experience of the European model of competencies and credits (European Credit and Transfer System (ECTS)) (Restrepo, 2008; Zarur, 2008).

Those projects are complemented by international pressures to follow "the trends expressed by different international organisations that endorse harmonisation and common grading qualification frameworks" (Díaz and Gómez, 2003, pp. 13-14). In

That inevitable change has brought about the questions of how these new credit systems are producing expected changes in terms of learning, curriculum management, student performance, and quality of education, among others, and how the managerial model for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) is prepared for the new scenario. Although limited, much of the international literature and the Colombian literature on the topic has studied the impact of credit systems and flexible curricula on the learning experience, curriculum management, and student performance. On one hand, Karseth (2005), Winter (1996), Morris (2000), Van Eijl (1996), Bocock (1999), and Allen and Layer (1995) describe how credit system implementation has changed curriculum conception, structure, coherence, direct implementation, and evaluation procedures. On the other hand, Naidoo (2003), Naidoo and Jamieson (2005), Jenkins and Walker (1994), Heffernan (1973), Agelasto (1996), Van Eijl (1996), and Watson (1989) discussed the impact of credit systems on the nature, process, quality, and outcome of learning, as well as on student identity, learner autonomy, interest in and depth of learning, and a redefi nition of teaching approaches. In the case of

However, the possibility of finding studies on how the HEI managerial model is prepared for or has changed for the new scenario is much more limited. That is because the system was implemented very recently in many countries and in others it was implemented more than eighty years ago so it is not possible to study the initial steps of the transformation, or the information regarding the change simply does not exist. Trowler (1998a) offers a good illustration of credit system implementation in the form of a case study although it is limited to a provincial department level. For

The study on administrative flexibility is broad and complex because management is a very specialized topic... therefore its treatment in this section is an introduction and may be considered an invitation to debate this problem which has huge incidence on HEI life. (Díaz, 2002, p. 109).

In addition to managerial changes due to credit system implementation, the literature on the topic tends to be not very systematic when it comes to presenting such changes. The most common manner of doing do is by using a list of expected / desired / actual changes (sometimes without much differentiation among the three), thus complicating the use of the results in a multi-case study.

Table 1 herein presents a grouping of the main managerial changes due to credit system implementation found in the literature on the topic. Table 2 summarizes the changes in a type of classification in an attempt to systemise the already presented results. Then the main changes are associated with transformations in within the institutions' governance, structure, culture, management practices, and expected resources.

According to Restrepo (2006), the other literature on credit systems either makes instrumental presentations of the topic, where credits are merely a tool to be implemented based on a previously defined method or makes political presentations, some in favour and others against it, but without proper justification.

In both of the above scenarios, the literature avoids scientifically developing the topic, and usually assumes a non-neutral position. The consequence is overestimation or underestimation of the topic, without reasonable argumentation. Cloonan alerts us of this issue by saying that "the use of the term flexibility has itself created a climate in which the kind of changes (that it generates) [...] are inevitably desirable [...] rather than elements which might be used judiciously" (Cloonan, 2004, p. 182). Examples of the instrumental version can be found in Duke (1995), Watson (1989), Agelasto (1996), and Allen Layer (1995), and examples of the political version can be found in Zgaga (2003); Tait (2003); Mason, Arnove, and Sutton (2001); Hawes and Donoso (2003), and Restrepo (2002). Watson (1989), Agelasto (1996), and Allen In both of the above scenarios, the literature Layer (1995), and examples of the political avoids scientifically developing the topic, version can be found in Zgaga (2003); Tait and usually assumes a non-neutral position. (2003); Mason, Arnove, and Sutton (2001); The consequence is overestimation or under-Hawes and Donoso (2003), and Restrepo estimation of the topic, without reasonable (2002).

To redress the limitations found in the literature on the topic, in a Colombian higher education scenario, this paper proposes a model approach to understand the managerial changes expected to occur in the HEIs due to credit system implementation.

1. An Initial Framework: The Credit System

Most descriptions of a credit system have three main flaws: they confuse the term with flexibility or with flexibility of provision; or they confine the concept to a very restrictive quantitative instrumental definition; or, in other cases, without the proper studies, the definitions conclude with non-critical justifications, overestimating the impact and the real power of change (Cloonan, 2004). This paper avoids such oversimplifications or overestimations of the concept; it attempts to conclude with a precise definition of scope, significance, and importance. To do so, in this paper the "credit system" is considered part of the concept of fl exibility.

Based on Ling et al. (2001), Rustin (1994), Green and Lamb (1999), Brehony and Deem (2005), Williams (2002), Bondeson (1977), and Restrepo (2006), flexible provision in higher education relates to the removal of constraints of time, place, contents, learning styles, forms of assessment, forms of access (entry and exit points in the program7) and manners to collaborate the learning, which have all limited the university experience. Defined in that manner, flexibility of provision may be implemented in different manners in higher education. One of them is the credit system although it must be clarified that flexibility is even possible without a credit system (Bekhradnia, 2004; Toro, 2006).

According to Reyes (2003), Toro (2006), and Restrepo and Locano (2005), academic credits must be understood in the context of a flexible policy in higher education which enables HEIs to develop new forms of curriculum design, curriculum organisation, and academic, pedagogical and managerial methods. Seen in that light, the credit system is not just a quantitative arrangement of the curriculum or a form of currency to help express learning in a quantitative manner (Bridges and Tory, 2001; Bekhradnia, 2004; Heffernan, 1973), a theory based on which it is very simple to end up with a "cafeteria model of education" in which students can individually choose their preference of subjects and build their preferred programme map adding up credits.

At any rate, the credit system allows quantification, to attain objectives, such as accumulation, transfer8, and acknowledgment9. Finally, in this paper, the credit system can not be conceived as an aggregation of tools, such as modularisation, semesterisation, franchising, and accreditation of work-based prior learning (Trowler, 1998a and 1998b).

This paper bases the concept of the credit system on the proposal that it corresponds to radical changes in terms of curriculum design, educational structure and content, provision (delivery) of education, the learning process and its assessment. Similarly, the concept should include the proposal made by Duke (1995), for whom the credit system includes changes in areas, such as curriculum and educational provision. In addition, this paper prefers a more complete defi nition in which the structure and content of education are included (Agelasto, 1996).

Finally, this paper has heeded the proposal made by Bridgland and Blanchard (2001), to include the learning process and its assessment in the credit system. In conclusion, this paper understands the credit system as a shift in paradigm regarding the structure, content, provision (delivery) mode, and learning assessment, which can be the result of different interrelated tools10.

2. Model for Understanding Changes in HEI Management due to Credit System Implementation

Having presented the concept of the credit system, keeping in mind the need for a model to enable understanding changes in HEI management, and now facing credit system implementation in

Table 3 summarizes different types of works. Some of them are related to national and/or international agencies which accredit HEI management and its performance (Wilson, 2005; Vroeijenstjn, 2001). Such agencies usually systemise the understanding of an HEI and its role in society into variables / factors. In this case, the idea was to extract the main variables referring to HEI management.

Other works relate to case studies which have analyzed HEI management and other comprehensive studies on changes in HEIs (Trowler, 1998a; Marginson, 2000; Margin-son and Considine, 2000). Finally, this paper contributes theories derived from recent studies on HEI management or on HEI change management (Deem, 1998 and 2005b; Schellekens, Paas and Van Marrienboer, 2003; Ferlie, Ashburner, Fitzgerald and Pettigrew, 1997).

This paper claims that it is possible to obtain three main categories of aspects which must be included when dealing with HEI management:

• Governance and structure: This category includes organisational forms and designs, directors' leadership capability, decision making systems, distribution of power, installations and infrastructure, and coordination procedures.

• Culture, values and, institutional identity: This category includes the institution's mission and vision statements, principles, and values, plus all proposed objectives and strategies.

• Managerial practices and techniques: This category comprises all of the tactics and processes used to manage the institution, including technologies, marketing, communication and information systems, control and assessment systems, funding process, resource allocation process, quality management, and budgeting, among others.

Finally, according to Wilson (2005), Trowler (1998a), Marginson and Considine (2000), and Díaz (2002), it may be helpful to evaluate management in terms of its relationship with the environment and how it is able to change, in order to redefine its governance, culture and management practices. Therefore, another category must be added. Relationship with the environment: This category will include the capability to compete internally and externally, convergence with and divergence from similar institutions, the capability to change, and resilience [the capability to adapt].

At any rate, two challenges must be addressed. The first challenge corresponds to the need for considering the particularities of the higher education system, especially regarding each institution's culture and its structural features (Gornitzka, 1999; Naidoo, 2003). The second challenge is to include the dynamics of such change. In other words, it demands studying the past, the present, and the future of the transformation as it occurs, avoiding "big bang" or "top down" interpretations of change, and moving towards "incrementalist" (Allen and Layer, 1995) and "transformational" (Ferlie et al., 1997) approaches.

3. The Case of Universidad del Rosario

The model and categories applied in this paper avoid tackling the two challenges expressed before for this kind of study; however this paper considers it feasible, based on this model, to build the structure of a preliminary case study to see how a particular HEI has transformed due to credit system implementation. Again, to reiterate, future research of this kind should include a combination of methods, to improve expected results. That is why this section is simply a "preliminary" stage in building a case study.

The case concerns Universidad del Rosario, a very prestigious university founded in 1653 by a Dominican priest named Fray Cristóbal de Torres. The educational emphasis at Universidad del Rosario has been on excellence in teaching, according to humanist, ethical values. Nowadays, Universidad del Rosario is one of 15 universities accredited for their to high quality standards. It is highly acknowledged for its teaching, research and, community services in

In 1990 the University identifi ed stagnation in its development and the need to adjust to the current environment. Because of the new national legislation11, many new institutions appeared in the higher education arena and developing robust educational projects, which inevitably competed against Universidad del Rosario. In fact, by 1994 the University was concerned with having failed to consider the pace and beat of present-day times:

... this turbulent period, which has broken the established paradigms through which we understood our reality, must be taken into consideration. These moments of transition [...] represent extraordinary development opportunities for those who perceive the sense and pace of change and are able to adapt to them through their actions. (Universidad del Rosario, 1995)

That year the University proposed a plan with four main courses of action: academic strengthening, education on Rosarism (institutional values), financial and administrative strengthening, and technological development. Today, in addition to those programmes, there are two new strategies: internationalisation and building an academic community.

The results achieved during the past ten years show a well consolidated university with 11,500 students, more research groups acknowledged by the main authority for Science in Colombia (Colciencias), all of the university programmes are accredited thanks to their high quality and have been built into the credit system, increased quantity and quality of full-time professors, new investments in the campus, technology, books, and research journals, software and hardware for teachers and students, and many other accomplishments12. The final achievement was that this University was the first Colombian HEI to carry out the quality assessment process led by the European University Association (EUA) in 2007.

As mentioned above, one of the changes introduced at the University was the adoption of the credit system as of 1997. Since then, few studies have been conducted to evaluate its impact. One of the reasons for this is that the University has been involved in hectic transformations, to stay competitive in a very difficult environment of new quality requirements and demands.

For the purpose of studying that change, and given the fact that this paper comprises a preliminary approach, a documentary, archive analysis was made, based on the concepts seen in case study literature (Yin, 1984), in which accessibility, accuracy, precision, and completeness are the main criteria for selecting the documents to be studied. Many papers which have dealt with this topic have used documentary analysis (Deem, 2005b; Allen and Layer, 1995; Marginson and Considine, 2000) combined, in some cases, with other methodologies. In this case, the documentary, archive analysis was based on reviewing the institution's educational project, two strategic plans (one for the 1998 - 2003 period and the other one for the 2004 - 2015 period), Rector Annual Reports (from 1998 to 2005), minutes of the committees in charge of credit system implementation, and the Institutional Accreditation Report (Universidad del Rosario, 2004c).

The first outcome corresponds to the initial reasons for introducing t the credit system and to the expected changes foreseen when the credit and flexibility policy was adopted. Introducing the credit system was a response to the changes in the higher education system, thus confirming the hypothesis expressed in the first part of this paper, "The dynamics of our society and our universities themselves demand movement, innovation and change, some of which will be permanent and others circumstantial [...]. The new reality and global trends have forced HEIs to give qualified, dynamic answers..." (Amaya, Hernández, Lombana and Nalus, 1997a, p. 3 and p. 16).

In particular, the credit system was aimed at attaining higher quality standards, improving the internationalisation process (especially regarding mobility), achieving greater flexibility, seeking answers to access and equity problems, and transforming the students' learning - teaching experience (Amaya et al., 1997a and 1997c).

After making the documentary analysis, at least two main waves of change may be identified. One of them comprises the 1997 - 2001 period and the other one is the period from 2002 to now. The first period moves in parallel with most of the University's first strategic plan and the second one moves together with the last part of the 1998 - 2003 strategic plan and with the 2004 - 2015 strategic plan. Both waves have had different emphases; the first wave of change defined the main expected changes and concentrated on the credit system implementation and conceptualization whereas the second wave of changes included consolidating the processes and reviewing the results of the first wave.

One of the main differences between the two waves is a clear change in the University's discourse, associated with different mission and vision statements in the two strategic plans. General concepts such as "active, creative education", "student-based education", "dialogue between students and professors" have been expressed since 2000 (Universidad del Rosario, 2005b and and 2001a); however, it has only been since 2005 that more precise, methodological strategies have been included in the discourse. In the current strategic plan, Universidad del Rosario has introduced strategies to implement the credit system, such as student mobility, the use of ICTs for teaching, curriculum reforms, drop-out rate reduction strategies, program diversification, organisational structure redesigning, and new resources (Universidad del Rosario, 2004b).

The first wave of change from 1997 to 2000 included two stages of change (Amaya et al., 1997a): one related to culture, planning and information and the other related to administration. The first stage included strategies to inform the academic community of the new credit system, as well as to inform them how the mission statement, education objectives, and the curriculum definitions had to change due to the credit system implementation.

The second stage which may be associated with changes implemented from 1999 to 2000 included reflections on how to renew the structure, the tuition systems, the registrar's office, and the admissions office, regulatory changes, new technologies, and credit system training for teachers, students, and administrative staff on the. The majority of the actual changes implemented at the University during the 1997 - 2000 period actually responded to the expected stages. Notwithstanding, it was clear that many of the actual changes which occurred at Universidad del Rosario outreached the expected ones, according to the initial credit system design.

Table 4 organises and compares the expected changes to the actual changes derived from credit system implementation, using the model proposed herein. On one hand, the table illustrates that the majority of changes have occurred in terms of management practices and techniques, particularly those associated with information and communication systems; financial policies; and departmental transformations; all of them directly related to the students' curriculum needs (admissions office and registrar's office).

On the other hand, the table shows that less attention has been paid to the institution's culture and values and to governance and structure. The result was a very complicated ambiance in the faculties that reflect the historical tradition of the university (Medicine and Law)13, where the system of credits was challenged and its true necessity questioned. Without a doubt, there were vast cultural differences between these two faculties and the others, which needed to be explained and studied in depth, in order to draw further conclusions.

In addition, there were more actual changes due to the credit system, than expected, especially in terms of management practices and the relationship with the environment. That reaffirms the need for a model for understanding the change, as well as the need for case studies, such as this one, to support and qualify preliminary conclusions.

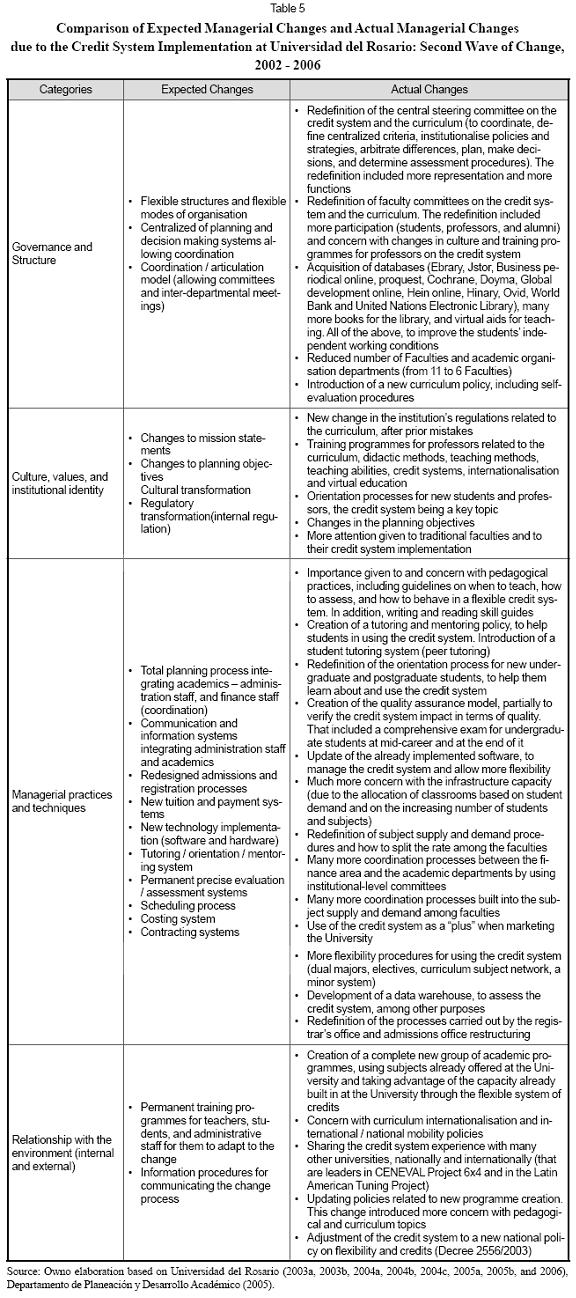

The second wave of change covers from 2002 to now and its results are systemised in Table 5 which compares the expected results versus the actual changes which occurred at the University. This period may be characterised as a consolidating moment but also as a period of time used to verify if the first wave had implied mistakes which had to be corrected. In fact, many of the changes in the second wave correspond to similar changes made in the first wave, in a current attempt, however, to avoid the difficulties previously experienced.

Another characteristic of the second wave of change is its emphasis on governance, particularly related to changes in resource availability and in structure modifications. More timid results may be associated with culture, values, and the relationship with the environment. Indeed, the cultural changes are basically related to training programmes although there is clear evidence of concern with how to integrate the credit system change into the University mission and planning statements.

Regarding the relationship with the environment, it is interesting to highlight the manner in which Universidad del Rosario's experience with credit system implementation is moving from being a learner in how the credit system impacts its management to a university whose experience can help other institutions when they implement the system. Presently Universidad del Rosario is a leader in many national and international HEI discussion groups on flexibility14. In terms of managerial techniques and practices, it is clear that the key word during this second wave of change may is "coordination".

The term coordination refers to the importance given to the manner in which academic subject supply and demand, the relationship between academics and the administrative area of the University, and the natural relationships and agreements among the different faculties may be better articulated. During this second wave of change emphasis was also given to the interest in using the credit system as a means to attain other University institutional planning goals.

That concludes the explanation of how Universidad del Rosario is using the credit system to easily introduce and create new undergraduate / postgraduate programmes, for its academic supply diversification. Similarly, other cases would be the introduction of the dual major program, the minor system15, and mobility, among others. Finally, it is also evident that during this second wave of changes there is clear institutional interest in student concerns and needs, other than the changes adopted in the first wave of change when there was a subtle emphasis on institutional needs.

Concluding Remarks and Future Research

This paper discusses a fundamental issue concerning Colombian universities, an issue that has not been treated much in the international and national literature on higher education: How has the managerial model of Colombian universities changed with the introduction of academic credit systems? To answer that question, this paper has studied one particular representative Colombian university, Universidad del Rosario. To do so, the paper broaches the case using archive and documentary information, from which it is able to extract some practical changes. This work may help Colombian universities in implementing the academic credit system, to avoid a lack of information on change due to credit systems, to not commit mistakes when introducing the system, to avoid trial-and-error implementation models, and misleading implementation cases which do not consider institutional particularities.

However, the work presented acknowledges certain limitations. It relies on an institutional view rather than an academic view (faculty, students, department or school level). In addition, there is a limitation in its inability to include a broader range of case studies and to make generalisations for other institutions, given its particularities and cultural setting.

Some will argue that it would be better to include more cases, to capture the particular idiosyncrasies of each institution. Therefore, a second stage for this work must include the dynamics of change, including the University's particularities and culture. To solve that problem, the literature on change proposes two possibilities: incrementalist approaches, in which culture and institutional particularities in a scenario of change are studied, to understand the causes, the process, and the consequences of such change and transformational approaches, in which change is studied dynamically in terms of its impact on the organisational forms, the distribution of power, product or service changes, new technology, and new culture.

Along the same lines, Pettigrew (1997, 1990 and 1979) contributed a methodological solution using longitudinal studies of change processes with comparative case studies16. That type of research links content, stakeholders, context, and change processes through time in a complex manner.

The other weakness to be solved is the inclusion of considerations on the particularities of the higher education system and on university culture. However, introducing the area of organisational culture into the research implies the dilemma of how to develop a proper model to understand such organisational culture and how to study the human stakeholders in an action context over a period of time. To solve that problem, many papers apply a questionnaire which assumes that organisations can be easily formatted and cultural impact easily defined. For future research, this paper recommends the inclusion of "in-depth" interviews in which "real life" situations are used to simulate the impact of change due to the credit system implementation on culture.

This paper raises the question of how these new credits systems can be managed in such a manner that universities may prepare themselves for this new challenge. To answer that question, the paper introduced the case of Universidad del Rosario, a traditional Colombian university which has transformed its institutional setting, to implement the credit system years before the legal requirement to do so. Based on the unsystematic literature on the topic, this paper offers a model which systemises change into four main categories: the University's governance and structure, its culture / values, and institutional identity, its managerial practices and techniques, and finally the university's dealing with the environment. This work concludes that, based on the case of Universidad del Rosario, normally speaking, the actual managerial changes exceeded the expected changes in all of the categories considered herein except in those related to culture, values, and institutional identity. In fact, institutional culture may be a key determinant in the nature of the of change process and in its expected duration. Most traditional faculties, for example, tend to react slowly to the implementation process. It is clear that credit systems lead to changes which, at the beginning of the process, may be unexpected; they are usually associated with more flexible forms of academic administration. That also means that change may lead to certain uncertainty and require an enormous ability to react to unexpected results.

The main managerial transformations relate to structural reorganisation and to the introduction of more centralized practices and techniques, to manage the credit system; the implementation of new fi nancial, registration, and regulatory norms which seek flexible forms of academic management and of academic supply; a new concern with pedagogical practices in search of active learning processes; and new demands and concerns regarding an infrastructure prepared for the change process.

The main managerial changes in the case of Universidad del Rosario follow the above pattern and relate to managerial practices and techniques and to the cultural setting. For the former, the accentuated changes relate to systems that facilitate the of communication process within the university and between it and its environment. That is the case of new admissions / registration systems, information systems, and financial budget systems. As concerns the cultural setting, the main changes correspond to new institutional regulations and to a clear curriculum institutionalisation process. That means practices and institutional organisation which facilitate curriculum coordination and arbitration.

In addition, the paper concludes with expected long-term transformations due to credit systems, such as structural reorganisation including a reduced number departments and faculties, concern with and transformations of infrastructure and logistics, and new options and opportunities derived from curriculum internationalisation and flexibility in creating new programmes (undergraduate and postgraduate). That means that, once implemented, credit systems may be a great determinant for future possible changes to help the institution become more concerned with its social demands.

One of the main conclusions is associated with some needs that a university must consider in the academic credit system implementation process. In particular, it must bear in mind the integration of the quality assurance system and the academic credit system and its consequences, the development and implementation of training programmes for teachers and students on the importance and impacts of credit systems, and the need to define or redefine tutoring and mentoring systems, to help students with the new flexible curriculum. Not meeting these parallel requirements may lead to a less successful implementation process, especially when requirements associated with the students' and the professors' attitudes are involved.

The particular experience of Universidad del Rosario, which may be extrapolated to other institutions, presents concerns with cultural and institutional particularities which can affect and distort the impact expected from introducing credit systems. In addition, it exhorts caution regarding the process dynamics and their importance concerning expected results and future stages of change.

Those two concerns require further research in which managerial transformations due to credit systems are combined with the structural and cultural particularities of each institution, faculty or department. A future line of research should draw attention to including other methods than the documentary, archive information method seen in models such as the one presented herein. Case studies of that nature must include interview data, informal conversation notes, observational data, and triangulation methods (which cross-check and cross-complete the research), to help reach more precise conclusions. At any rate, the model is important as a preliminary means to characterise university management and how it may be affected by credit system implementation.

Although this paper only gives preliminary results, it is important because it introduces a topic which is scarcely treated in the national or international literature on higher education. In fact, much of the research conducted on the credit system impact on management ends with a rather simple, linear list of expected changes, without proper guarantees. As a consequence, the literature either overestimates or underestimates the change and ends with descriptions of expected changes, without considering the importance of actually experiencing the expected changes. In the preliminary case study included herein, change may be characterised in two stages, one relating to the credit system implementation and the other to its initial consolidation.

In the case of Universidad del Rosario, after eight years of credit system implementation, this paper contributes new notions on how to improve such implementation. Topics such as the need to revise the organisational structure (in an attempt to make it more interdependent), organisational decision-making and coordination policies, strategies to improve the introduction of the credit system into the institutional culture, and reflection on the capability for future change using the credit system, must all be on the future agenda. Furthermore, internal studies on how different cultures (for ex., traditional faculties vs. contemporary faculties) react to credit system implementation may also an interesting line of research.

Other aspects that may be considered, based on the experience of Universidad del Rosario, are identifying the key drivers of managerial change due to the credit system and how to deal with contingencies. In the latter case, it is recommendable to include methodologies in which the change dynamics, the stakeholders' opinions and cultural settings (students, professors, and administrative staff) in the research. Using those aspects may make it possible to understand why actual changes due to the credit system may outreach those expected, as occurred in the Universidad del Rosario case or perhaps just the opposite may be seen in other particular cases.

Footnotes

1. And also ICFES, the Colombian Institute for the Development of Higher Education.

2. As stated by Díaz and Gómez (2003), that project implies four topics: the debate regarding general and specific competencies, the introduction of cycles into the various educational levels (bachelor's degree -master's degree - PhD), learning methods, and credit system harmonization.

3. CENEVAL (Mexican National Assessment Centre) leads that project; it is attempting to harmonize 100 Higher Education Institutions in South America and Central America, in terms of competencies, education for research and innovation, accreditation, and credit systems.

4. Defined by the CNA (Colombian National Council for Accreditation).

5. Díaz (2002) confirms this based on the results of workshops and surveys carried out in 2002 at most of the higher education institutions in

6. Includes works which study credit systems in terms of "Flexibility of Provision" or modularization.

7. That can be related to examples such as "cycle" education or "modularisation", meaning a manner to divide the programme into small parts with clear entry and exit procedures. Europe gave an example of this when it defined the undergraduate cycle and the Masters'and PhD cycles and how they are all interrelated and complementary.

8. Giving students the possibility of mobility within the educational system and, at the same time, accumulation of their learning.

9. Giving students a method for formally acknowledging their success in learning.

10. Tools such as modularisation, the definition of value / credit in assessed learning, semesterisation, accreditation of prior learning, etc... .

12. The best manner to support that remark is to refer to the "Self-evaluation Process" that took place at the University, which led to the "Institutional Accreditation". That achievement implied that the external community was publicly informed of the high quality of the institution under the national higher education quality model. Today there are only 15 universities in

13. In fact, one of the problems which the University faced in 2003 was a clear reaction against the credit system, in particular from those traditional faculties.

14. The CENEVAL Project 6x4, for example. A project in which more than 100 universities around Latin America are working on a Credit System for the region, based on competencies and with a clear emphasis con quality assurance.

15. The minor system corresponds to a model based on which any Universidad del Rosario student may obtain a degree accompanied by a diploma (certifying that the student has a minor in a certain topic upon attaining 12 to 20 credits in that subject [minor]); for ex., students who obtain a degree in Economics from the Faculty of Economics plus a minor in International Business from the Faculty of Business Administration.

16. According to Pettigrew, that means "... studying change in the context of interconnected levels of analysis [... (introducing)...]temporal interconnectivity, locating change in past, present, and future times... exploring [...] how context is a product of action and vice versa...and...how the causation of change is neither linear nor singular [...]. The longitudinal comparative case method provides the opportunity of examining continuous processes in context and drawing on the significance of various interconnected levels of analysis" (Pettigrew, 1990, pp. 260-271).

References List

1. Agelasto, M. (1996). Educational transfer of sorts: the American credit system with Chinese characteristics. Comparative Education, 32 (1), 69-93. [ Links ]

2. Allen, R. and Layer, G. (1995). Credit based systems: As vehicle for change in universities and colleges. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

3. Amaya, G., Hernández Trillos, M., Lombana, A. and Nalus, M. A. (1997a). El sistema de créditos: una alternativa para la construcción de una universidad que anticipe el futuro: marco preliminar (anexo 1). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

4. El sistema de créditos: una alternativa para la construcción de una universidad que anticipe el futuro (anexo 2). (1997b). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

5. El sistema de créditos: una alternativa para la construcción de una universidad que anticipe el futuro. Documento operativo. (1997c). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

6. Bekhradnia, B. (2004). Credit accumulation and transfer, and the Bologna process: an overview. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute. [ Links ]

7. Bocock, J. (1999). Curriculum change and professional identity: The role of the university lecturer. In J. Bocock and D. Watson (Eds.), Managing the university curriculum: Making common cause (pp. 116-116). London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

8. Bondeson, W. (1977). Open learning: Curricula, courses and credibility. Journal of Higher Education, 48 (1), 96-103. [ Links ]

9. Brehony, K. J. and Deem, R. (2005). Challenging the post-Fordist / flexible organisation thesis: The case of reformed educational organisations. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 26 (3), 395-414. [ Links ]

10. Bridges, P. H. and Tory, J. H. (2001). Credits, qualifications and the fluttering standard. Higher Education Quarterly, 55 (3), 257-269. [ Links ]

11. Bridgland, A. and Blanchard, P. (2001). Flexible delivery / flexible learning...does it make a difference? Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 32 (3), 178-191. [ Links ]

12. Burke, P. and Carey, A. (1995). Modular developments in secondary and further education: their implications for higher education. In Developing student capability through modular courses (pp. 43-48). London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

13. Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organisational pathways to transformation. New York: Elsevier. [ Links ]

14. Cloonan, M. (2004). Notions of flexibility in

15. Deem, R. (1998). New managerialism and the higher education: the management of performances and cultures in universities in the

16. Globalisation, new managerialism, academic capitalism and entrepreneurialism in Universities: Is the local dimension still important? Comparative Education, 37 (1), 27-30.(2001). [ Links ]

17. The knowledge worker, the manager-academic and the contemporary

18. New managerialism and the management of UK universities, end of award report of the findings of an economic and social research council funded project October 1998-November 2000. (2005b). Lancaster: Department of Educational Research and the Management School-Lancaster University ESRC award number. [ Links ]

19. Brehony, K. J. (2005a). Management as ideology: The case of new managerialism in higher education. Oxford Review of Education, 31 (2), 217-235. [ Links ]

20. Departamento de Planeación y Desarrollo Académico (2005). Proceso de renovación curricular de pregrados. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

21. Díaz Villa, M. (2002). Flexibilidad y educación superior en Colombia (2nd ed.). Bogotá: ICFES-Ministerio de Educación Nacional. [ Links ]

22. Gómez, V. M. (2003). Formación por ciclos en la educación superior. Bogotá: ICFES-Ministerio de Educación Superior. [ Links ]

23. Duke, C. (1995). The learning university: Towards a new paradigm (2nd ed.). London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

24. Ferlie, E., Ashburner, L., Fitzgerald, L. and Pettigrew, A. (1997). The new public management in action (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

25. Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Newtony, H., Schwartsman, S., Scott, P. and Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. New York: Sage. [ Links ]

26. Gornitzka, A. (1999). Governmental policies and organisational change in higher education. Higher Education, 38 (1), 5-31. [ Links ]

27. Green, P. F. and Lamb, D. J. (1999). Effective flexible delivery in higher education: An Australian case. Dowloaded on 24 November 2008 from http://is2.lse.ac.uk/asp/aspecis/20000137.pdf. [ Links ]

28. Hawes, G. and Donoso, S. (2003). Organización de los estudios universitarios en el marco de la declaración de Bologna. Talca, Chile: Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Educacional. [ Links ]

29. Heffernan, J. M. (1973). The credibility of the credit hour: The history, use, and shortcomings of the credit system. Journal of Higher Education, 44 (1), 61-72. [ Links ]

30. Jenkins, A. and Walker, L. (1994). Developing student capability through modular courses. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

31. Karseth, Berit (2005). Curriculum restructuring in higher education: A new pedagogic regime? Paper presented at the Third Conference on Knowledge and Politics at the University of Bergen, Bergen,

32. Ling, P., Arger, G., Smallwood, H., Toomey, R., Kirkpatrick, D. and Barnard, I. (2001). The effectiveness of models of flexible provision of higher education, evaluation and investigations programme. Sidney: Higher Education Division, Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs. [ Links ]

33. Marginson, S. (2000). Rethinking academic work in the global era. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 22 (1), 23-35. [ Links ]

34. Considine, M. (2000). The enterprise university: power, governance and reinvention in

35. Mason, T. C., Arnove, R. F. and Sutton, M. (2001). Credits, curriculum, and control in higher education: cross national perspectives. Higher Education, 42 (1), 107-137. [ Links ]

36. Monroy Cabra, M. C. (1998). Flexibilización curricular y creación del sistema de créditos. Bogotá: Facultad de Jurisprudencia, Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

37. Morris, H. (2000). The origins, forms and effects of modularisation and semesterisation in ten UK-based business school. Higher Education Quarterly, 54, (3), 239-258. [ Links ]

38. Naidoo, R. (2003). Repositioning higher education as a global commodity: Opportunities and challenges for future sociology of education work. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 24 (2), 249-259. [ Links ]

39. Jamieson, I. (2005). Empowering participants or corroding learning?: Towards a research agenda on the impact of student consumerism in higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 20 (3), 267-281. [ Links ]

40. Ortiz, C. (1998). Estructuración y montaje del área de registro académico centralizado en el departamento de admisiones. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

41. Pettigrew, A. M. (1979). On studying organisational cultures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 570-581. [ Links ]

42. Longitudinal field research on change: theory and practice. (1990). Organisation Science, 1 (3), 267-292. [ Links ]

43. What is a processual analysis? (1997). Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13 (4), 337-348. [ Links ]

44. Restrepo, B. (2002). Calidad y flexibilidad en la educación superior. Document presented at Foro de la Universidad de San Buenaventura, Cartagena. [ Links ]

45. Restrepo, J. M. (2002). La apertura y flexibilidad curricular como respuesta al problema de la equidad. Revista de la Educación Superior, 123 (31). Downloaded on 24 November 2008 from http://comunidad.ulsa.edu.mx/public_html/academica/posgrados/documentos/lecturas/flexibilidad_curricular.docc. [ Links ]

46. El sistema de créditos académicos en la perspectiva colombiana y Mercosur: aproximaciones al modelo europeo. (2005). Revista de la Educación Superior, 34 (135), 131-152. [ Links ]

47. Restrepo, J. M. (2006). Flexibility and academia credits within higher education trends. Mimeo assignment-paper for the DBA in Higher Education Management. Bath: University of Bath. [ Links ]

48. Innovaciones en la implementación de sistemas de créditos en América Latina: aprendizaje del Proyecto 6x4. (2008). No publicado. [ Links ]

49. Locano, F. (2005). El sistema de créditos académicos en la perspectiva colombiana y del Mercosur. México: Ceneval. [ Links ]

50. Reyes, M. T. (2003). El sentido de los créditos académicos. Interacción. Revista de Comunicación Educativa (32). Downloaded on 24 November 2008 from http://interaccion.cedal.org.co/documentacion.htm?x=14221andcmd[126]=c-1-%2732%27. [ Links ]

51. Rustin, M. (1994). Flexibility in higher education in towards a post-fordist welfare state. In: Burrows, R. and Loader, B. (Eds.), Towards a postfordist welfare state (pp. 177-202). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

52. Schellekens, A. D., Paas, F. and Van Marrienboer, J. J. G. (2003). Flexibility in higher professional education: A survey in business administration programmes in the

53. Slaughter, S. and Leslie, L. L. (1999). Politics, policies, and the entrepreneurial university. New York: The John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

54. Slaughter, S. and Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state and higher education. New York: The John Hopkins University. [ Links ]

55. Tait, T. (2003). Credit systems for learning skills. London: Learning and Skills Development Agency Reports. [ Links ]

56. Toro, J. R. (2006). Flexibilidad curricular y créditos. Borrador-Mimeo. Bogotá: Ministerio de Educación Nacional-Asesorías. [ Links ]

57. Trowler, P. R. (1998a). Academics responding to change: New higher education frameworks and academic cultures. London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

58. What managerialists forget: Higher education credit frameworks and managerialist ideology. (1998b). International Studies in Sociology of Education, 8 (1), 91-110. [ Links ]

59. Universidad del Rosario (1995). Planes y programas 1995-1996. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario [ Links ]

60. Universidad del Rosario (1998a). Cuadro comparativo de la evaluación del software para oficinas de registro. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

61. Actas del Comité Veedor de Créditos Académicos 1-37. (1998b). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

62. Informe ejecutivo del sistema de créditos. (1998c). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

63. Inquietudes de tipo presupuestal y administrativo: sistema de créditos. (1999). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

64. Proyecto Educativo Institucional (PEI). (2001a). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

65. Universidad del Rosario (2001b). Informe de Gestión 2000. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

66. Informe de Gestión 2001. (2002). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

67. Informe de Gestión 2002. (2003a). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

68. Actas del Comité Institucional de Currículo. (2003b). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

69. Informe de Gestión 2003. (2004a). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

70. Plan Integral de Desarrollo 2004-2015. (2004b). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

71. Informe final de autoevaluación institucional. (2004c). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

72. Informe de Gestión 2004. (2005a). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

73. Proyecto Educativo Institucional (PEI). (2005b). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

74. Informe de Gestión 2005. (2006). Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

75. Van Eijl, P. J. (1986). Modular programming of curricula. Higher Education, 15, 449-457. [ Links ]

76. Vicerrectoría, Departamento de Planeación y Desarrollo Académico (2004). Lineamientos institucionales para la gestión curricular. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario. [ Links ]

77. Vroeijenstjn, A. I. (2001). Towards a quality model for higher education. Document presented at INQUAAHE-Conference on Quality standards and Recognition. [ Links ]

78. Watson, D. (1989). Managing the modular course. London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

79. Williams, J. B. (2002). Flexible assessment for flexible delivery: preliminary results and tentative conclusions.

80. Wilson, L. (2005). Institutional reforms to improve governance: Enabling European higher education to make its full contribution to the knowledge society and economy. Brussels: European University Association. [ Links ]

81. Winter, R. (1996). New liberty, new discipline: Academic work in the new higher education. In Cuthbert, R. (Ed.), Working in higher education. London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

82. Yin, R. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

83. Zarur, M. X. (2008). Integración regional e internacionalización de la educación superior en América Latina y el Caribe. En Tendencias de la educación superior en América Latina y el Caribe. Cartagena: Unesco-IESALC. [ Links ]

84. Zgaga, P. (2003, September). The Bologna process between Prague 2001 and Berlin 2003: contributions to higher education policy. Rapporteur for the Berlin Conference. [ Links ]