INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative movement disorder associated with the selective loss of dopamine (DAergic) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc). Although the specific molecular mechanisms leading to neuronal death in PD are not yet fully understood1, increasing evidence from human and animal studies has suggested that oxidative stress (OS) plays a major role in the cell death process2. Circumstantial and epidemiological studies suggest that PD can be induced with environmental toxins that inhibit mitochondrial complex I (e.g., rotenone, ROT)3. ROT is often used to model PD in vitro and in vivo4)(5. Interestingly, Xu and co-workers6 have shown strong evidence for an association between low cerebral glucose (G) metabolism and the severity of PD. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that dysregulation of G metabolism is an early event in sporadic PD7. Despite these advances, no information is available to explain the relationship between OS, abnormal G metabolism, and neuronal demise in PD. Most importantly, the understanding of the molecular mechanisms that control neuronal survival during OS and bioenergetics crisis is essential for therapeutic intervention in PD.

Lymphocytes represent a dopaminergic system to analyze the phenomenon of OS in this neurological disorder8)(9. Specifically, we10)(11 and others12)(13)(14)(15)(16 have used lymphocytes to understand the relationship between OS phenomena and PD. Previous studies have shown that ROT induced apoptosis in lymphocytes in a concentration- and time-dependent manner by a molecular signaling mechanism under standard G condition (i.e., 11 mM G, hereafter 11 G)17. ROT toxicity thus appears to result primarily from OS signaling. Interestingly, the authors also reported that high G concentration (55 mM) abates ROT-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes17. However, the mechanism(s) by which high G protects lymphocytes against OS is not yet established.

The aim of the present work was to evaluate the survival response of lymphocyte cells cultured with different G concentrations in the absence or presence of ROT. Our findings might contribute to understanding the mechanism of cell resistance/death signaling under stressful conditions. Taken together, our data suggest G metabolism should be considered as an additional dietary factor to be properly monitored and adjusted to confront OS and combat neuronal demise in PD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) if not otherwise specified and were of analytical grade or better. The 3,3’-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (Di Oc6 (3), Cat. #D-273) and dihydrorhodamine (DHR, cat. #D-633) were obtained from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA).

Isolation of lymphocytes

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from venous blood of healthy adult males (ages ranging from 30 to 40 years old) were obtained by gradient centrifugation (Lymphocyte separation medium, density: 1.007 G/M; Bio-Whittaker), according to ref.17.

Experiments with peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL)

Assessment of cellular viability (CV) in PBL by light and fluorescence microscopy analysis using trypan blue (TB) and acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) double staining.

The PBL cells, at a cell density of 1 x 106 cells/mL, were exposed to ROT (250 microM) in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco/Invitrogen reference # 11879-020) in the absence (0 mM corresponding to 285 mOsmol/L) or presence of glucose (11, 55, 166, 277, 555 (mM) G), corresponding to 296, 340, 452, 563, 3 400 mOsmol/L, respectively) and different products of interest for 24 h at 37 °C. The PBL were then used for light and fluorescent microscopy analysis, according to ref.17. The apoptotic index was assessed three times in independent experiments blind to researchers.

Determination of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Assessment of superoxide anion radical generation

Lymphocytes (1 x 106 cells/mL) were exposed to ROT (250 microM) in the absence or increasing concentrations of glucose (G 11, 55, 166, 277, 555) under similar experimental conditions as mentioned above. Superoxide anion radicals (O2 .-) were evaluated with nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) reagent, as described in ref.17. The assessment was repeated three times in independent experiments.

Assessment of hydrogen peroxide (H 2 O 2 )

PBL cells (1 x 106 cells/mL) were incubated with ROT (250 microM), and increasing concentrations of G. H2 O2 was detected in PBL cells by using the sensitive, uncharged, non-fluorescent dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR), as described in ref.17. The experiments were performed in three independent settings. Parallel to O2 .- and H2 O2 evaluation, apoptotic cell percentage was established according to AO/EB staining.

Assessment of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (delta psi mt)

The PBL were treated as described above. Then, cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with cationic lipophilic DiOC63 (1 microM, final concentration) to evaluate (delta psi mt), according to ref.17. The experiments were performed in three independent settings.

Assessment of LY-294002, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO), 1,3- Bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU or carmustine), 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (AT), sodium diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC) and mercaptosuccinic acid (MS) inhibitors on lymphocytes exposed to rotenone in high glucose

The PBL cell suspension (1 x 106 cells/mL) in 55 G was pre-incubated with LY294002 (5 microM, specific PI3K inhibitor), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (5, 50, 100 microM, specific glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) inhibitor (18,19), 1,3-Bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) (10, 100 microM, specific glutathione reductase (GR) inhibitor)20, mercaptosuccinic acid (MS) (10 mM, specific GPx inhibitor), 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (AT) (25, 50 mM, specific catalase [CAT] inhibitor)21, and sodium diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC) (0.5, 1, 5 mM, specific SOD inhibitor)21), for three hours, or pre-incubated with L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO) (1, 5, 10 mM, specific γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase (g-GCS) inhibitor21) for 24 h at 37 °C before exposure to ROT (250 microM). PBL were then evaluated for apoptotic morphology and (delta psi mt), as described above. The optimal concentration of inhibitors reported in Table 1 was based on our previous experience with inhibitors (e.g., 5 microM LY294002 and 10 nM PDTC (17), based on cited literature (e.g., 50 mM DHEA)19, or based on the minimal concentration at which maximal inhibition and/or non-toxic effects were reported.

Table 1 Effect of glutathione, metabolic and signaling inhibitors on lymphocytes cultured in 55 mM glucose (55G) medium with or without rotenone (ROT, 250 mM) exposure

Immunocytochemistry detection of NF-kB, p53, and caspase-3 transcription factor proteins

The supplier’s protocol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, goat ABC Staining System: cat # sc-2023) was followed for immunocytochemistry using primary goat polyclonal antibodies NF-kB p65 (C-20)-G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology cat#sc-372-G), p53 (FL-393) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology cat #sc-6243-G), and cleaved caspase-3 p11 (h176) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology cat #sc-22171-R).

RESULTS

Glucose protects lymphocytes against rotenone (ROT) irrespective of ROS and in a concentration and time-dependent fashion: Effect on the (delta psi (mt)

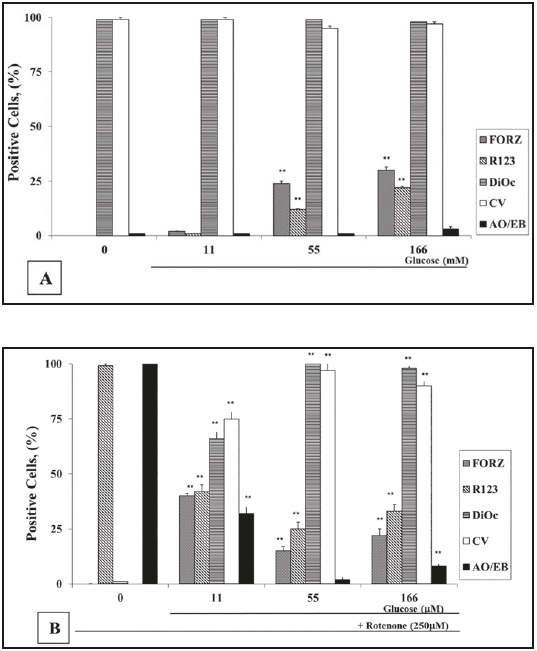

To establish the PBL response to G and ROT, we initially exposed cells to increasing concentrations of G (0-555) alone or in combination with ROT (hereafter 250 mM). As shown in Figure 1A, lymphocytes cultured in glucose-free medium (GF) or G alone up to 166 G induced almost no apoptotic morphology (i.e., 0-2 ± 1 % AO/EB staining). Higher G concentrations provoked apoptotic morphology (i.e., 30 ± 3, 68 ± 3, and 96 ± 2 % AO/EB at 277, 388, and 555 G, respectively). As expected, ROT induced apoptosis in lymphocytes, but the percentage of apoptotic cell death was heterogeneous. Cell death was reduced by 70 % in the presence of 11 G and ROT (i.e., 32 ± 2 % AO/EB staining positive cells), while ROT in GF medium induced 100 % AO/EB apoptosis. Interestingly, ROT toxicity was further decreased (i.e., 2 ± 1 % AO/ EB) when co-incubated with 55 G (Figure 1B), but ROT-induced apoptosis slightly increased (i.e., 8 ± 2 % AO/EB) when co-cultured with 166 G (Figure 1B). Cell viability (CV) evaluated with trypan blue staining inversely matched the percentage of nuclear morphological changes assessed with AO/EB staining (Figures 1A and B). AO/EB staining was selected for further apoptotic morphology evaluation, because the evaluation of morphological cell changes by this method was validated as the most reliable method for the detection and quantification of cell death in terms of percentage of apoptosis, when compared to other methods22.

Figure 1 Glucose (G) protects lymphocytes against rotenone (ROT)-induced apoptosis independently of reactive oxygen species. (A) Lymphocytes (1 x 106 cells/mL) were incubated with increasing concentrations of G (0, 11, 55, 166 (mM)) either alone or (B) in combination with ROT (250 microM) for 24 h at 37 °C. The evaluation of O2 .-, H2 O2 , apoptosis, and (delta psi mt) were performed as described in the Methods section. The percentage of positive formazan (FORZ), R123, Di OC6 (3) high-polarized mitochondria, cell viability (CV) and AO/EB stained cells are expressed as the mean of percentages ± SD from three independent experiments

It is known that either G or ROT generate ROS23)(24. As shown in Figure 1A, 55 G and 166 G moderately produced superoxide anion (O2 .-) and H2 O2 , as determined by nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction into formazan (FORZ), and dihydrorhodamine (DHR) into rhodamine-123 (R-123) staining, respectively. PBL cells cultured in GF medium and 11 G showed either non detectable or low O2 .-/H2 O2 production, respectively. By contrast, H2 O2 was dramatically increased in cells treated with ROT in GF medium (i.e., almost 100 % R-123), but no O2 .- was detected (Figure 1B). Interestingly, when ROT was co-incubated with 55 G or 166 G, the percentages of O2 .-/H2 O2 positive cells were almost constant (i.e., 15-22 % FORZ and 25- 33 % R-123), but ROS were higher in 11 G and ROT (40 % FORZ and 42 % R-123). A similar effect was detected in cells exposed to higher G concentration alone such as 277 G and 388 G (55-60 % FORZ and 33-26 % R-123, respectively), but extremely low percentages of O2 .- (5 ± 1 % FORZ) and H2 O2 positive cells (4 ± 1 % R-123) were identified in the cells treated with the highest (555 G) concentration of G (data not shown).

ROT inhibits the mitochondrial NADH-quinone oxidoreductase complex; we therefore evaluated the effect of ROT on the mitochondrial membrane potential (delta psi mt) on cells cultured in G at different concentrations. PBL exposed to ROT in GF medium induced a complete mitochondrial depolarization (i.e., 0 % DiOC6 (3)high positive cells). By contrast, no effect on mitochondrial potential depolarization was observed when PBL were incubated with 55 G - 166 G and ROT (Figure 1B) or G alone (Figure 1A). Noticeably, lymphocytes exposed to ROT with 11 G induced moderate mitochondrial potential depolarization (Figure 1B). Since 55 G was found to be a minimal concentration that almost completely protected lymphocytes against ROT-induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization and apoptosis, this concentration of G was thus used for further experiments.

We then evaluated the time course of H2 O2 generation, mitochondrial depolarization, and nuclear morphological changes in PBL treated with ROT in GF and in 55 G. PBL exposed to ROT in GF medium steadily produced H2 O2 over time with a maximum percentage value at 24 h compared to cells cultured in GF medium alone. Noticeably, the apoptotic morphology and mitochondrial depolarization were detected after 3 h of ROT incubation. Although H2 O2 generation was produced at low percentage levels over time when cells were exposed to ROT and 55 G, no mitochondrial depolarization or apoptotic morphology were detected under this treatment condition (data not shown).

Glucose protects lymphocytes against rotenone through the pentose phosphate pathway

Once G enters the cell, it can participate in at least two metabolic pathways, namely the glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathways (PPP)25. The former pathway turns glucose to pyruvate, which either turns into Acetyl-CoA, an essential molecule in the generation of ATP through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and mitochondrial potential, or it may react as an antioxidant on mitochondria26)(27. Therefore, we investigated the role of pyruvate in ROT-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes. PBL cells were therefore incubated with increasing concentrations of sodium pyruvate (1, 5, 10, 25 mM SP) in the presence or absence of ROT (250 microM) in GF medium. SP alone was innocuous to cells. Given that lymphocytes produced no detectable H2 O2 in GF medium, no antioxidant function of pyruvate was evaluated. However, almost 100 % apoptotic morphology, mitochondrial depolarization, and H2 O2 production were detected when cells were cultured with ROT together with SP (data not shown).

These observations prompted us to evaluate the role of the PPP in this paradigm28. PPP converts glucose to NADPH. This last compound reduces glutathione (GSH) via glutathione reductase (GR), which converts reactive H2 O2 into H2 O and O2 by glutathione peroxidase (GPx). We also evaluated the importance of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) as antioxidant enzymes in ROT-induced death in this PBL model. As described in Table 1, except BSO, all inhibitors provoked moderate increments in the percentage of apoptosis (25-30 %) and mitochondrial depolarization (20-35 %) in cells treated with ROT compared to cells exposed to the inhibitor alone or 55 G (control).

Glucose protects lymphocytes against rotenone induced apoptosis through NF-kB activation and p53 and caspase-3 inhibition

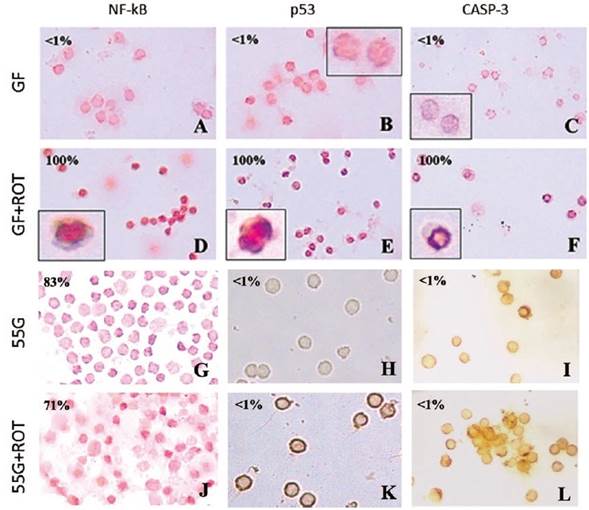

To further characterize the molecular response of PBL to ROT intoxication, cells were left in GF or 55 G in the absence or presence of ROT. As depicted in Figure 2, PBL in GF medium alone showed normal nuclei morphology with no detectable death markers, i.e. 0 % DAB+ nuclei of NF-kB, p53, and caspase-3 (Figures 2A-C), whereas ROT in GF medium induced cell shrinkage and 100 % DAB+ (apoptotic) nuclei (Figures 2D-F). Strikingly, PBL cells exposed to ROT and 55 G or 55 G alone showed NF-kB activation (Figure 2G: ~52 % DAB+ (non-apoptotic) nuclei; Figure 2J ~48 % DAB+ (non-apoptotic) nuclei), but p53 and caspase-3 expression were negative, i.e., ~1 % DAB+ nuclei (Figures 2H, I, K, L).

Figure 2 Glucose induces NF-kB activation and p53 and caspase-3 inhibition. Lymphocyte cells (1 x 106 cells/mL) were incubated in glucose-free (GF) medium (A-F) or glucose (55 (mM) G) (G-L) or treated with ROT (250 microM) in GF (D, E, F) or 55 G (J, K, L) for 24 h at 37 °C. Cells were stained with anti-NF-kBp65 (A, D, G, J), anti-p53 (B, E, H, K), and anti-caspase-3 (C, F, I, L) antibodies according to the procedure described in the Methods section. Notice that NF-kB, p53, and caspase-3 positive-nuclei (numbers represent the percentage of positive (%) dark brown colored nuclei) reflecting nuclear translocation/activation. Magnification 400x (A-G, J), 600x (H, I, K, L), inset magnification 800x

To confirm the involvement of signaling molecules in lymphocyte cell death induced by ROT, PBL were treated with PDTC (10 nM, specific NF-kB inhibitor), PFT (50 nM, specific p53 inhibitor), and NSCI (10 microM, specific caspase-3 inhibitor) in either GF or 11 G alone or in combination with ROT for 24 h at 37 °C. All inhibitors reduced ROT-induced apoptosis (e.g., 9-11 % AO/EB) and increased mitochondrial membrane potential (e.g., 85-87 % DiOC6 (3)high positive cells) when cultured in the presence of 11 G compared to cells incubated in 11 G and ROT (e.g., 34 % AO/EB, and 64 % DiOC6 (3)high, respectively). It is noteworthy to mention that inhibitors were ineffective at protecting lymphocytes against ROT-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial depolarization when cultured in GF medium (data not shown).

Glucose protects lymphocytes against rotenone through PI3K activation

We evaluated whether the activation of PI3K was involved in lymphocyte resistance to ROT-induced oxidative stress, because NF-kB was activated and mitochondrial potential was not impaired in lymphocytes even in the presence or absence of ROT in 55 G. Thus, PBL cells were incubated either with LY294002 (5 microM) alone, or in combination with ROT in 55 G. Table 1 shows that the presence of LY294002 blocked the protective effect of 55 G in lymphocytes against ROT-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial depolarization compared to cells exposed to ROT and 55 G.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows for the first time that high glucose (55 G) was effective in suppressing ROTinduced apoptosis in lymphocytes via five pathways, involving (i) the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), (ii) the glutathione (GSH) pathway, (iii) the SOD and CAT antioxidant systems, and (iv) PI3-K signaling. Moreover, it is also shown for the first time that G induced lymphocyte survival through (v) NF-kB activation and down-regulation of p53 and caspase-3. These experiments revealed the complex nature of G protection in cells. This conclusion is based on the following observations. We confirm that ROT generates O2 .-/H2 O2 , which was associated with decreased (delta psi mt) and morphological apoptotic nuclei under standard culture conditions (i.e., 11 mM glucose, 11 G), as described in ref. (17). In accordance with those observations, lymphocytes cultured in GF and exposed to ROT displayed the typical morphological characteristics of apoptosis such as drastic cellular volume diminution, chromatin condensation and/ or nuclei fragmentation concomitantly with a complete mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Interestingly, 55 G was able to maintain (delta psi mt) potential and nuclear morphology against ROT toxicity to control values. These observations comply with the notion that G provides the cell’s energy by serving as a primary substrate for the generation of ATP, thereby providing (delta psi mt) maintenance and cell survival. Indeed, pyruvate which is a natural metabolic intermediate en-route to the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle, may exert antioxidant activity, thus inhibiting (delta psi mt) collapse and apoptosis. However, we found that sodium pyruvate (SP, 1-25 mM range), as sole energy source, did not protect lymphocytes against ROT-induced apoptosis. Moreover, the percentages of apoptosis and mitochondrial depolarization were similar to those observed when lymphocytes were cultured in GF supplemented with ROT. Although our data clearly suggest that SP did not protect lymphocytes against ROT-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis, we do not discard the possibility that SP may serve as an H2 O2 scavenger under other specific experimental conditions (e.g., lymphocytes exposed to ROT in the presence of G plus SP). Our data thus suggest that G metabolism in non-dividing cells might be preferentially routed through the PPP28)(29 rather than the glycolysis pathway, which is the prevalent G metabolic route in active dividing cells when challenged with oxidant stressors30)(31. Interestingly, the inactivation of the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by H2 O2 may serve as a cellular switch to reroute the metabolic carbohydrate flux from glycolysis to the PPP under OS conditions32.

We found that except BSO, all other metabolic and signaling inhibitors moderately reversed 55 G-induced survival in lymphocytes under rotenone exposure. These data suggest that G produces functional redundancy (i.e., one part in a system can completely or partially compensate the loss of another) to ensure global cell protection against stress stimuli. Several considerations support this view. First, as a consequence of the pharmacological blockage of G6PD, the supply of NADPH in lymphocyte cells can be fulfilled through several one-step enzymatic reactions catalyzed by NADP+-dependent dehydrogenases from the Krebs’ cycle, by pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase powered by the proton motive force, and/or by NADH kinase which directly phosphorylates NADH to form NADPH33. In case of PPP breakdown, glycolysis might take over NADPH production, but G is absolutely required to run the defense mechanism. Second, blockage of glutathione system might activate other NADPH-dependent oxidative defense systems such as thioredoxin reductase and peroxiredoxin protein34. One may conclude therefore that the continuous supply of NADPH depends on G availability and on the cyclic metabolic PPP/glycolysis network.

Taken together, our data comply with the notion that lymphocyte cells have alternative metabolic pathways to combat OS, even in circumstances in which some of the key enzymes fail to accomplish their function by either accident (i.e., pharmacologic inhibition) or by genetic defects (e.g., G6PD mutations). These data further suggest that ROT kills cells predominantly through OS17)(35, and that a proper source of NADPH, GSH, and antioxidant functioning enzymes must be warranted for lymphocytes to undergo complete resistance to ROT-induced OS. Collectively, these data and ours suggest that pharmacological inhibition, deficiency, or genetically altered expression of the cellular antioxidant proteins are critical components of response to stressful conditions and that these antioxidant systems act in a cooperative way to ensure cell protection. It is worth mentioning that lymphocytes (and neurons) exposed to extremely high glucose concentrations induce OS, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis (e.g., 277 and 388 G)36. We concluded that optimal cellular protection against stress stimuli is achieved only when there is an appropriate balance between G and GSH metabolism via the PPP pathway, and the activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx are maintained.

The NF-kB plays a critical role in cellular metabolism37. We have demonstrated that 55 G alone or in combination with ROT was able to induce the activation of NF-kB. Moreover, NF-kB was activated by ROT in lymphocytes cultured in GF medium. Since both G and ROT generated ROS, it is reasonable to think that a common molecule (e.g., H2 O2 ) might be responsible for NF-kB activation in both experimental settings. In accordance with this view, H2 O2 -induced NF-kB through the indirect activation of kinases38, which in turn phosphorylate the IkBa inhibitor as well as p65- two molecular components of NF-kB39)(40)(41. Remarkably, we also demonstrated for the first time that the pro-apoptotic transcription factor p53 was undetectable when cells were co-incubated in 55 G and ROT, but it was evidently activated by ROT in lymphocytes cultured in GF medium. Consequently, a connection between NF-kB and p53 is clearly established in lymphocytes under different conditions. These data thus comply with the notion that the activation of NFkB is necessary but not sufficient to promote survival or induce apoptosis in lymphocytes42. Accordingly, we found mitochondrial depolarization and caspase-3 activation concomitantly with apoptotic morphology in lymphocytes exposed to ROT in GF medium. Taken together, our data suggest that activated NF-kB might induce pro-apoptotic proteins which balance the cell fate towards death response in cells under limited or nil amounts of G combined with ROT (or H2 O2). On the contrary, activated NF-kB induces anti-apoptotic proteins which balance the cell fate towards survival in a cell under optimal G concentration (e.g., 55 G) and ROT. Interestingly, NF-kB also up regulated g-GCS expression and enzyme activity in human bronchial epithelial NCI-H292 cells (43), thereby keeping GSH available in response to OS. These data suggest that G might promote gene transcription of survival and G metabolic genes via NF-kB activation and suppress gene transcription of pro-apoptotic proteins through p53 inactivation.

It is known that the PI3K-protein kinase B (PKB, also known as Akt) pathway serves as a central pivotal component of cell survival and G transport pathways. We found that pharmacological inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 reversed the survival effect of G against ROT in lymphocytes. This observation suggests that PI3K might be implicated in G-induced survival signaling in lymphocytes. Indeed, it has been shown that Akt enhances both the ubiquitinizationpromoting function of Mdm2 (murine double minute) and Mdm2 protein stabilization by phosphorylation of Ser186, Ser166, and Ser188, which results in the reduction of p53 protein44)(45). Based on our present data, it is reasonable to assume that p53 is modulated by G through the PI3K-Akt pathway46. Our findings therefore reveal that p53, but not NF-kB, is the critical transcription factor that may possibly balance the expression of pro-death proteins towards intracellular death decision under noxious stimuli.

Recently, Yoon and Oh47 have shown that high G levels (> 17.5-35 mM) protected MN9D cells (i.e., dopaminergic neuronal cells) against 1-methyl-4 phenypyridinium (MPP+)-induced apoptosis via downregulation of caspase-3 activation, DNA fragmentation, and ROS inhibition. Taken together, these data suggest that high G levels modulate DAergic neuronal and lymphocyte cells response against stressful stimuli by suppressing OS and apoptosis-induced pathways. This information may contribute to a better understanding of the intracellular molecular mechanism by which G promotes cell survival against OS. Indeed, in the brain in vivo, about half of the G leaving the capillaries is transferred down its concentration gradient via facilitated diffusion on the GLUT-1 transporter from the lumen (approx. 100 mM G) to the brain extracellular space (approx. 60 mM G) to neuron cells (approx. 30 mM G) via the GLUT-3 transporter48. Recent data suggest that dysregulation of G metabolism might represent an early metabolic biomarker of sporadic PD (6). Because lymphocytes express GLU-1 and GLU- 3 transporter proteins49, display molecular death machinery50, and G metabolism25 similar to neurons8)(47)(51, we consider that lymphocyte cells represent a remarkable non-neural cell model to understanding the signaling and metabolic regulation of apoptosis in response to stressful stimuli. Therefore, the metabolism-OS-cell death axis is a fundamental issue in the therapeutic design to prevent, delay, or ameliorate the treatment of individuals at risk of PD as encountered in Antioquia, Colombia52.