Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Papel Politico

Print version ISSN 0122-4409

Pap.polit. vol.12 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2007

MODELLING A TWO - ACTOR NEGOTIATION PROCESS IN A CONFLICT CONTEXT

MODELO DOS - PROCESO DE NEGOCIACIÓN DEL ACTOR EN UN CONTEXTO DE CONFLICTO

Manuel Ernesto Salamanca1 Daniel Castillo M.2

1 PhD Marie Curie Guest Postdoctoral Researcher EU Commission - Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University Researcher - Teacher, political science and International Relations School Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

2 Phil PhD Candidate CIRAD, Université Paris 10 - Nanterre's Teacher, School of Rura and Environmental Studies Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Recibido: 28/02/07 Aprobado evaluador interno: 09/04/07 Aprobado evaluador externo: 12/04/07

Abstract

From the concept of intractability of armed conflicts, this article intends to develop a modelling exercise of negotiation between the actors involved. Through representation this joint, conceptual effort examines relations between elements constituting a negotiation process, assuming that the possibility to negotiate is a way to overcome deep-rooted, protracted, resolution-eluding conflicts. The model conceived is, at the same time, a working hypothesis and a functioning conclusion on the possibilities of negotiation from actors choices.

Key words: modelling, complexity, armed conflict, negotiation, intractability, conflict resolution, representation

Resumen

Desde el concepto de intratabilidad de los conflictos armados, este artículo pretende desarrollar un ejercicio de modelamiento de una negociación entre los actores involucrados. A través de la representación, este esfuerzo conjunto y conceptual examina las relaciones entre los elementos que constituyen un proceso de negociación, asumiendo que la posibilidad de negociar es una forma de superar los conflictos arraigados, prolongados y que han eludido iniciativas de resolución. El modelo concebido es, al mismo tiempo, una hipótesis de trabajo y una conclusión funcional sobre las posibilidades de la negociación desde las decisiones de los actores.

Palabras clave: modelo, complejidad, conflicto armado, resolución del conflicto, representación.

The following exercise is a representation effort. It intends to theoretically and graphically discuss the reach of a modelling technique in order to apply it to the analysis of armed conflict. It departs from the assumption that armed conflicts may evolve from intractability to tractability through processes of negotiation. Intractability of political, violent conflicts seems to pose a big problem for the field of conflict analysis and resolution of disputes.3 In fact, the question of deep-rooted, violent conflicts and their apparent resistance to well intentioned techniques of conflict settlement, to put it simply, engenders conclusions like assuming that certain situations are eternally violence-prone, do not belong to the interest of the usual mediation and negotiation agents, and thus should be left to their inner process of exhaustion. Internal conflicts should not be all remediable, and in that sense some appear even as incurable, which makes them eligible to fulfil their own destiny of irresolution, establishing a crucial difference between the irresolvable ones and "those with reasonable prospects of resolution, should preoccupy us".4 This paper does not agree with the tragic vision of intractable being synonymous with incurable. Intractability here is understood as a temporary condition of certain confrontations. Though sometimes long, this condition is mainly evolving, meaning that a conflict might transform itself from intractability to tractability, which also implies that it can re-evolve towards intractability, and so forth. Conflict life, if not cyclical, might be seen as a continuum.5

One might then presume that an intractable confrontation is a situation of conflict in which two (relative) conditions are present:

a) They are long, protracted conflicts (relative condition);

b) They are irresolvable (relative condition) in the sense that they have eluded diverse attempts of a negotiated agreement as settlement.

The combination of duration and non resolution results in the intractability of the confrontation though it is clear that the limits of the concept are not clearly defined: how long is long? How deep is deep? How wide is wide? This is the reason to call the above conditions relative. It is not possible to say from when an armed confrontation is considered long or protracted, neither when it objectively has become difficult to resolve. To do so, one could think of the number of peace settlement initiatives through which certain confrontation has gone through, and the ways by which their forms of success and failure determine bigger or lesser violence intensity. In the same manner, this operation could be carried out inversely: analyse in which forms violence influences the development of the negotiation processes tending to armistice.6

Nonetheless, Putnam and Wondolleck7 suggest levels of objectivity to determine what intractability really is by their variable dimensions: divisiveness, because of the level of division they generate and the multiple types of polarization they imply; intensity, focused on their levels of emotion involved and the types of compromises that warriors assume with the conflict; pervasiveness, by the way a conflict spreads and wells on human lives; and the most important, complexity: the authors understand it as resulting from the various interwoven issues and the layers of social systems in which the conflict resides. This deserves a deeper reflection, according to the purposes of representation of this work.

Having said this, what then is representing a conflict? It is, on the one hand, choosing a conceptual framework from which the representation operation can be carried out. In fact, this document will presume that such a framework is system dynamics, and that conflicts are systems, thus susceptible of representation through diverse methodologies. It is, on another dimension, an operation of simplification, by which a social phenomenon can be reduced to a point of visibility and reduced to a level of conceptual manipulation, hypothetically operated and informed with data.

Nonetheless, very paradoxically, reduction and simplification can only result from the condition of complexity of the situations that are going to be represented. In fact, complex as armed conflicts generally are, in terms of grasping their nature it is necessary either to carry a selective, partial analysis, or to select a specific characteristic or situation of the conflict in order to represent it. Totality is impossibility, but aggregation is a way to gather pieces of reality in order have a better understanding of the complex phenomena feeding a dynamics of conflict.

It could be a matter of scale, or proportion given the fact that we can only observe phenomena from a point of view. From a strategic approach to the dynamics of armed conflict, one could assume that an armed conflict is a relation of violent exchange between at least two factions with diverse levels of organization, each having its own internal structure and power hierarchy. Organizations with high level of coordination produce results of action visible at the larger scale, while fractioned entities acting within the dynamic of a conflict reduce the level of visibility of their actions to a more detailed scale.8 This means that the more fractioned a certain organization is when it gets involved into a dynamic of conflict, the more specific the analysis that must be carried out, for its level of action belongs to the specificity of its own internal, fractioned structure.

Of course, this adds to complexity, and if, as Bar-Yam puts it, "complexity is a measure of the number (variety) of possible ways a system can act",9 then one can presume that the environment where the action is undertaken may itself acquire a higher level of complexity because of the complexity of the actors' exchange (i.e. violent agencies), that is their way of building a relationship.

For the case of an armed conflict such a relation is based on exchanges of violence, being these overt or latent (direct use or threat of violent action). Such exchange, key to understanding the basis of a relationship of violent nature, is in some form the motive of the system of conflict functioning, being necessary then to explore it, characterize it and hopefully model it, in order to identify patterns or common features of violent exchanges between organizations.

This work intends to do precisely that: reduce to representation the complex dynamics of a conceptually intractable armed confrontation having in mind the process of it becoming tractable. In doing so, the representation process intends to identify common phenomena and divergent situations leading to the situations considered to be intractable. It will also suggest the paths of action by decision makers (actors of conflicts) that may lead or not to tractability, understanding this latter concept as a point in which the conflict becomes negotiable. The work also assumes that the partial views it will represent, being these related to the decision processes of actors involved directly and indirectly in the process of confrontation, will provide a notion about the general system of conflict they belong to. This is not an operation of addition, but of aggregation, taking into account the paradoxical levels of inclusion upon which system dynamics is based.10

In fact, one can presume that a conflict is a system of interrelations between contending parties. This system (not yet deeply defined) has no option but to be included into another interrelation system (i.e. a political environment, a country, a territorial entity), though it is completely and substantially different from the latter. And, nonetheless, it functions as a completely different set of elements and relations, fulfilling at the same time a function of total differentiation and total equivalence for, being included, is at the same time part of the inclusive system and other than it.

Keeping this into account, it is possible to understand the value of complexity when interpreting social dynamics, such as conflicts. When taking complexity as a framework for analysis, one can say that the aggregation of fractions may produce a more general, holistic view of the situation's specificities. In fact, complex interpretations provide a broad view of a panorama, in the sense that the smaller the levels of description, the more there is to describe in detail and vice versa, noting that "at each scale the entire system is being described, not just a part of it".11

The system dynamics approach to analysis of social situations will provide us with tools that may be of use to have combined information at the macro and micro levels,12 in the sense that some interactions might be taken at the micro-levels in order to have a clearer picture of the macro systems where events of confrontation take place. In fact, rationalities functioning and interacting and adapting or mal-adapting to diverse transformations and situations might be a sort of indicator of the general system functioning. It becomes then necessary to grasp that the nature of collective action becomes a matter of analysis in order to understand the relation between the micro levels of decisions taken within social systems and the macro levels of the functioning of such containing systems.

The latter implies that the type of analysis that will be carried out through this comparative analysis will intend to be multi-layered. Multi-layered, in this case, does not mean that a layer of reality covers another, or superimposes to another, but that events and relations occur in a simultaneous manner in which a hierarchy of facts cannot be constructed: in fact, no relation of simple causality will help to understand reality, and even less to represent it in a comprehensible form. Representation is not reality and does not intend to replace it. But certainly, representation is here intended to bring a degree of visibility to the interpretation of a social dynamics such as conflict while getting into the depths of multi-causality. This is the reason to undertake a multi-layered operation of representation, having on one hand the decisions taken by social systems such as organizations involved in conflict and on the other the realm where the exchanges between factions take place.

It is pertinent to follow Sterman in order to understand why the representation of complex systems might be enlightening to comprehend their functioning and relations of multi-causality. It will be presumed that a certain confrontation (with the potential of becoming violent) behaves as a system of relations and elements, such as actors, situations, acts (agencies) and communications interrelating all of them. There is, nonetheless, a clarification that must be made: though system dynamics has been widely applied to biological systems, this is not a "biologization" of a conflict dynamics.13 Simply put, but not only because of that, the fact that a great value on non-rationality is taken into account when representing the systems considered is a proof of how non biological or physical this description operation shall be.

In order to establish the basis of a conceptual framework, the piece will combine two different and presumably complementary approaches to systems and to system dynamics applied to social systems. On the one hand, a theoretical, basic approach elaborated by Niklas Luhmann in his "Social Systems", and on the other a more practical, model-design orientation drawn by John Sterman in his "Business Dynamics - Systems Thinking and Modelling for a Complex World" (2000).

It seems plausible to assume, with Sterman, that "complex systems are in disequilibrium and evolve" and that "many actions yield irreversible consequences". In the case of an act of violence, just to give an example, it is notorious that once an act of violence has taken place it cannot have not taken place. It is also presumable that the instability characterizing the dynamics of conflict (in general - not only armed) derives from the many variables and multi-causal combinations that one can think of in terms of greed, grievances, values, resources, beliefs and motivations of actors in contention sharing a space and a moment in time. Since the variation of variables can occur simultaneously, interpretation can become confused (Sterman). But grasping it is a matter of recognizing what complexity and systemic are about, where they coincide and where they determine each other (Luhmann).

To start, it is possible to be basic: in a projection (and applied development) of Sterman's categories explaining that "Dynamic complexity arises because systems are…" to certain basic concepts of conflict interpretation of analysis, one can presume:

1. Systems of conflict are dynamic: if all is change, instability situations such as conflicts can be nothing but change. In fact, the life of a conflict might be drawn as a continuum of constant transformation that starts with transformation. The emerging moment of a contradiction or problem evolving into a confrontation14 implies that there is a point in time in which there is at least a dramatic change in the conditions of a certain environment: that in which the situation of conflict begins to occur. This implies that the relation of actors also transforms into a conflict one, and that contention is now the nature of their exchange.

2. Since systems of conflict are "tightly coupled" it is crucial to understand that the perceptions of actors involved in a conflict situation is in relation with the realm they are involved in and the other actor(s) participating more or less actively in the contention situation.15 In fact actors decide, in confronting other's interests, a relation of rivalry or cooperation; and regarding the realm they are immersed in, they can decide whether they compete for a certain good of interest or not.

3. Systems of conflict are governed by feedback: beyond the evidence of the logic of contention, in which it is plausible to presume an exchange of bargaining or even aggression (in the case of violent conflicts), the actors feeding each other's decisions with decisions more or less rationally taken while facing the contender's choices, change the panorama of the system containing them as systems of collective nature. From these decisions of contention, new scenarios emerge, thus the general scenario is inevitably and constantly transformed.

4. There is non-linearity in the functioning of the exchange of contention decisions, nor in the response of the system to the logic of contention. In fact, one cannot presume that in the logic of contention the response of a given actor will be equivalent or based on reciprocity in relation with the other actor's. It is also unpredictable the degree of affectation that a certain containing system will suffer because of the non reciprocal logic of action-reaction carried by the systems of decision takers included.

5. The system of conflict is clearly history-dependent: conflict does not occur anywhere (there is a topos for every conflict) and is certainly informed by its own self-referential history of contention. This means that the framework to carry a dynamic analysis of contention has to be time-dependent and historically informed. Just as what has happened cannot have not happened, things happen because of a multiplicity of causes and contexts, all relative to a moment or moments in time.

6. The system of conflict tends to self-organization: the narratives of actors of conflict16 and the decisions they take affect the general system in a definitive form, very much unpredictable. In fact, the adaptation (Luhmann, Sterman) processes derive in an organization in which the system adapts to the transformation caused by actors, while at the same time the agents of contention adapt themselves to the other actors and to the transformation of the system, in a successive stream of feedbacks. Organization of the system is, then, self-referential and constantly altered by following its own changing rules.

7. The system tends to adaptation: organizations and persons "learn" from experience, just as systems "learn" from the behaviour of the subsystems, such as human organizations, composing and determining them. Then, the goals of actors and systems themselves may vary through time, re-conducting history and the functioning of the diverse containing systems related between them through processes of aggregation.

8. Systems of contention may be counterintuitive: no single, neither proximate or structural causes may explain the nature of an event by themselves; neither an event may derive logically from a given act. Agents of contention act and react guided by rational and non-rational aspects of their own self-organization and personalities. As such, there is no linearity of events, thus intuitions or presumptions about the behaviour of organizations and systems may frequently fail.

9. Systems of conflict may tend to be policy resistant: being non-predictable, self-referential and self-organizing, dependent on decisions of rational and non-rational nature, the systems of contention may not be obvious in their functioning, neither in the application of initiatives or policies to resolve them. For the cases this work will take into account, the only obviousness can apply to the fact that resolution policies have constantly and frequently failed.

10. Systems of conflict are certainly characterized by trade-offs, not only because actors of conflict may tend more or less to negotiations, again the obvious, but in a broader sense: exchanges of information, determined by levels of communication and of penetration of systems within systems, result in affectations and feedback cycles between realms, organizations and people.

If the discussion has been conducted towards representing intractability of armed confrontations, it certainly must include a component in which the process towards tractability is also taken into account. One could say that tractability comes when, all of a sudden or in a process, conflicts become ripe enough so that negotiation is the path that follows in the dispute's dynamics. Models of ripeness have been widely discussed, and go from the conscience of armed actors about their own tragedy if the fighting does not end, towards the positivity of finding in negotiation an opportunity to overcome violence.17 Though processes of armed confrontation may tend to be long, it is possible also to assume that ripeness arrives in an instant, a point in which the decision to negotiate emerges from a process of long, collective construction of diverse types of confidence between enemies.

Such dynamics results from political needs or military needs by which actors need to change perspectives. In fact, one could describe such transformation as a very complicated, sometimes unwilling, change of perceptions. It is a starting point in which, for reasons covering from politics to the recognition of self inability to win an armed contention, the collective rationality must obey the leaders' command in order to think the unthinkable - that is, perceiving the enemy as someone with the dignity of a recognisable, legitimate, worthy, counterpart. This is another twist of the nature of collective action: hierarchies may indicate that the history of hostilities has to change, in order to start talking politics; and then, if the negotiation succeeds, sign peace.

The warrior's honour is again challenged, in terms of the multiple transformations it is subjected to: first, from individually having the options of not being a contender - enemy, to start belonging to a certain collective logic by which a person must obliterate rivals in the name of the group's rationality; second, to develop an enemy-enemy relation in a specular manner with individuals whose status is that of the one to obliterate; third, when politics arrive, the common rationality indicates that a certain confidence building process needs to be started, since the objectives of the battle have changed and are to be replaced by the logics of dialogue.

Certainly, simplified as it has been presented, the above process cannot be easy. And it cannot be not because peace is not desirable, but because people act and feel, and they are not simply rational in all circumstances, especially if rationality (when a group or collective matters) is subjected to tremendous changes during its timeline. In fact, for combatants, peace may be traumatic, not because they do not desire it, but because the incertitude it brings are as big as the engagement as the fight.

On the one hand, one cannot forget that, in building confidence preparing the field for a negotiation or peace agreement, the steps and measures are to be taken collectively with those who have been enemies up to the start of the contacts. It is the enemy that the combatants are now to deal with, in a different, dialogical reason that indicates how all of what was perceived before of foes is now and suddenly, not held true.

On the second hand, the so called opportunities of the negotiation, usually perceived through the rationale of politics, have to be translated into a communal rationality by lines of power in which the former combatants are simply forced to understand. This occurs, needless to say, because the interpretation is in general an individual operation that, once again, is here transformed by no natural means in a communal one.

The combatant - ex-combatant by means of politics - becomes a dialogical subject that was only self-referential before (his decisions did not regard the good for his enemies, in fact they regarded their bad). If he understands, that is a different matter. Again, he is brought to behave and believe collectively, in terms of the group's welfare and interest: the combatant sacrifices again, this time through the believing act of getting to know that everything that he was asked to do before is not correct anymore. He has to believe and act differently, because the common good of his coreligionists, and more, because the concept of the common good has been extended to his former enemies. Negotiation and reconciliation are so, conceptually, proven to be not easy tasks.

Levels of confidence certainly affect the way people interact. It has been proven by diverse economic experiments,18 that regarding the administration of Common Pool Resources (CPR), people reach agreements and change their behaviours according to diverse levels of confidence they build between groups. In fact, this is the overcoming of the famous tragedy of the commons, according to which rational actors face their fate of being rational and thus exhaust the common goods for they have no reasons to organize themselves in order to reach strategies for sharing.

This work does not intend to be as simple as an extrapolation of the science behind the theory of management of common pool resources to the levels of the ways in which people, firstly, get involved in armed conflicts and then, secondly, resolve them through negotiation. But certainly one can think about a certain level of conceptual common goods that can be understood as resources by which common rationalities may compete and / or cooperate.

Having said this, one can presume that at the level of complete and radical non-cooperation, one finds conflict (and even violent means) as a way to resolve disputes; one can also presume the contrary, which is that cooperation leads towards a common, agreed upon administration of such conceptual goods, and that is towards negotiated agreements.

Let us then, try to describe what from the common pool resource theory may be of use in order to describe a way in which disputes may be thought about, both in terms of analysis and resolution. The discussion must evolve in a very systematic form, from the basics of understanding how the dispute may emerge, how the management of the goods may occur, and how the conflict may be resolved. It is basic in a dual manner: both because it can be at the basis of the emergence of the dispute, and because it can be somehow fundamental.

Common goods in a peace and negotiation process: what is a good, and what is a common

One could think of goods as consumable resources belonging to the public realm of societies or to the realm in which human beings must compete for them. The first are goods not subject (at least conceptually) to exclusion mechanisms. The second are subject to exclusion processes, for while appropriated by one of the stakeholders they are taken out of reach to the other. Usually, firsts are the first are thought of as public goods, while the second are seen more as Common Pool Resources (CPRs).29 Theoretically, public goods, by being public, are not for the people to compete, for their use is guaranteed to everybody. Air is a good example. Though in the current days it may not be so, air is supposed to be as public as it can be, since everybody is entitled to breathe it and formally no competition should be conceivable over this resource.

Ostrom has widely discussed the nature of goods, through theoretical and experimental evidences.20 It is worth quoting literally: "Private goods, which are characterized by the relative ease of exclusion in an economic and legal sense and by subtractability, are the commodities best analyzed using neoclassical economic theory of markets. Public goods are the opposite of private goods in regard to both attributes. Toll goods (sometimes referred to as club goods) share with private goods the relative ease of exclusion and with public goods the relative lack of subtractability. Common pool resources share with private goods the subtractability of resource units and with public goods the difficulties of exclusion."

The theory of the Common Pool Resources states that some potential or actual users may be excluded, mainly in terms of the scarcity of a certain resource, or the perception of the scarcity of a certain resource by the actors contending for it. That is the reason for economists to drive the discussion on CPRS towards the proper administration of them, and to the institutional arrangements that humans reach in order to share such resources, collectively. As such, this is one of the reasons to have collective action as one of the driving forces of the studies on institutions and, in general, human organizations.21

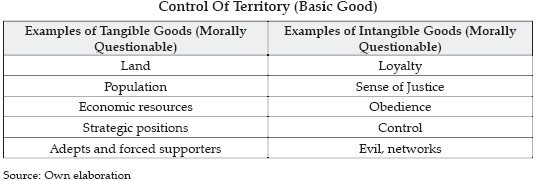

Having said this, one can easily imagine that the study of resources subject to appropriation might be feasible and plausible. In fact, it is possible to number the ways by which contention and organization of groups can occur in order to determine how each one tends to appropriate a certain common pool resource and how in common they can agree on its commonality. Models shown have assumed diverse possibilities of territorial appropriation, and the contentious attitude of actors has been translated into the dynamics of their violent agency transformed into a kind of zero sum environments: the territories appropriated by one of them are no longer territories belonging to any other. Victory, in this sense, might mean the more territory one can appropriate, for it means that political violence and violent agency have reached a physic goal.

Problems may arise when considering common goods that are intangible. Keeping in mind the example of the territorial appropriation one can certainly make divisional operations by which the strength of a certain actor might be measured in terms of its appropriated area. Nonetheless, territories are not empty. They are populated, so territorially speaking one cannot assume simply that actors only expect to have more land when exercising their violent agency. They also want more people under their sphere of domination. This domination might be understood in terms of obedience: for the Colombian case, actors do not actually take possession of a territory and dwell on it. They prefer to carry out scattered attacks (mainly towards civilians) and construct what might be understood as an area of influence.

It is possible to see this dynamics in municipalities of diverse departments in Colombia, and specifically regarding the territorial control around the cities, in a strategy that might be called "peripheral": armed illegal actors of the conflict do not enter the cities, for doing so would imply that they become visible to the legal forces combating them. It has been proven how around cities like Bogotá -the capital-, Medellín and Cali there is a combination of factors that facilitates control by the armed groups: illegal forces profit from unsatisfied basic needs; illegality, and economic informality, are taken profit of by the illegal forces. They settle there, establish a sort of social control in these zones and even combat with each other. Their ambition is to have a territorial, mental control in the periphery in order to perform armed actions against the cities, and in the case of Bogotá there are documented combats between guerrillas (FARC - Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and paramilitaries; also, between diverse paramilitaries groups themselves.22

Specifically, Garzón describes how paramilitaries carry a full social control operation in the surroundings of Bogotá, zone of the Altos de Cazucá, combining raids by private armies with no uniforms but face-covered, control of transportation means, expulsion to all of those who they may consider collaborators of the guerrilla (the zone has been frequently identified as a camp for guerrilla urban militias, but also is an arrival point for thousands of displaced people - whose attempts to form organizations have been violently jeopardized), and social cleansing (physical elimination of delinquents, drugaddicts and sellers, sexual workers, and any "undesirable" person). This is said to be a security control and anti-guerrilla campaign, but at the end it is in reality a strategy to control illegality in the area. More than that, paramilitaries charge inhabitants and business owners with fees that "guarantee" their safety fulfilling a double strategic function: they extort inhabitants economically, and also carry an information control operation. Through fear, nothing moves without the paramilitary cell's knowledge. Also, it has been described how paramilitaries exercise a covered control on the zone through urban gangs by them infiltrated and commanded. Years before this occurred, guerrilla groups had the same modus operandi in the area.

As seen in the above example, if territory might be taken as a resource, there is a variation in the nature of the resource that belongs to the exercise of force:

a. Territory can be understood as a public good, in the sense that inhabitants of the zone have a right to it, just as other citizens arriving to the zone may have it. Territory should not be in discussion, it is for inhabitants to dwell on. Though spatially it is evident that there can be exclusion, in terms of a republican-citizen oriented political order, citizens of a country should be able to live wherever they choose.

b. Territory can be a private good if, according to the laws of the market, it is acquired by someone and becomes object of property titles. Territory is easily subtractable and perfectly fits exclusion, when bought. Evidently, violence can be another means by which territory can be appropriated and made a private good, for the agency of violence lays out an appropriation dynamics that corresponds with the use of force by actors possessing the means to cause violence, intimidate populations and thus illegally take possession of areas.

c. Territory can be interpreted as a toll good in the dynamics of the violence described before. It can be inhabited if fees are paid to the "safety" guarantors, who actually are building a paid network of information and control. They decide, in a sick assignment of club value to a good, who can live and who has to leave a specific territory. Toll then, is not voluntary, but absolutely mandatory in order to acquire a temporary dwelling right from the violently turned owner actor of appropriation.

d. In the specific sense of the CPR theory, one can describe territory as subtractable in terms of the resource units and certainly object of exclusion. If the competence for a territory is a zero sum game, in which what is dwelled by some, simply cannot be dwelled by others, one can understand how actors competing violently for a specific territory intend to create their own realms of control. This control cannot be but absolute, if the nature of the violent competition for a territory is violent. In fact, territory, interpreted as subtractable and excludable by agents of violence, is violently fought for in order to have it become a private good. That can be interpreted as the final task of the violent agency.

This has been the interpretation of the physic condition of the territory. But there is an intangible condition that may be understood in terms of the diverse natures of a good so competed for. The appropriation of populations, for actors in violent competition for dominance, can also be seen as a natural process that goes along with the territorial resource. It sounds sick and it is in fact more than perverse. But that does not mean that the appropriation of populations does not belong to the practical rationality of contenders.

Populations can be measured in numbers, certainly. But people are not an inert good, for people move, think, react, feel, experience, last, live… People also change, and the processes of exercise of political violence, in general, produce definitive transformations both in victims and perpetrators. As the author has repeatedly claimed,23 once violence has happened, it cannot have not happened, which indicates that the transformation power of violence is definitive. In fact, it is through processes of violence that people are displaced, that they are threatened, and also that they become victims. From the perspective of the perpetrators people start to belong to a collective rationality instead of privileging their individual one.

History divides in the before, the while and the aftermath of violence, when the agency occurs. Conflict resolution theoreticians and practitioners should understand that their work has to take into account such temporal differentiation. Acting on violence and thinking about violence have different meanings when considering the temporality of violence. That cannot be stressed enough. By now, this work will focus on the populations appropriated, and on the goods they may represent according to the violent actor's rationalities. In violence, that is in violent conflict - the least cooperative situation of all, realities acquire meanings through tremendous tergiversation.

When people are somehow appropriated by a dynamics of territorial appropriation (people live in territories), the final task of the violent agents is that of achieving full control over the mentioned piece of land. Means are surely horrid, since violent agents use threatening strategies as the ones described above, but in practice they belong to a rational choice by which the objectification of human beings may guarantee that something more than territories and human beings dwelling on them are resources for which to compete violently.

Morally, this document is questionable: to equal land and people as appropriation-prone resources might be as hideous as "understanding" that the logic of violent actors is that of a rationally directed character or agent of violence. The collective "I" described here is able to carry out equalization operations by which it has to have a conceptual trip from the physical to the conceptual: when appropriating land, it also appropriates what's in it: people. But people are not subjects of appropriation as such. In fact, and back to morality, they are not objects to appropriate, though they become a good for which to compete.

How that occurs is a conceptual operation, carried out in the rational collective and common rationality of the violent actors: it is a very complicated step, though simple the task-oriented rationale of violence might appear. It implies that control becomes a good, for to achieve control (a negative form of governance) it is necessary to acquire dominance over a certain area. It is necessary to remind the reader that armed factions, at least in the case of Colombia (later the Basque particularity will be discussed), do not actually build camps or inhabit the territory they dispute for: they prefer to act as a network of relations controlling illegality and criminality, as described, in order not to be evident, nor visible. Control, then, is a non tangible, a concept.

But the concept is made out of concepts, itself. What constitutes control? Certainly, control is a disputable good. Control is also a fiction, for the absolute power that the absolute control over a territory supposes is impossible. No matter, for example, how arbitrary a government can be, it can never reach the total control of the territories under its aegis. Armed groups, in the case described, know they will not acquire a complete control over the totality of the territory of a country, so they ensure they control parts of it, specific and prone to be taken. Such is the case with the outskirts of big cities, so prone to criminality and to illegality that, as suggested, also become prone to appropriation goods (that may actually be called "bads."

Having said this, it is necessary to venture a definition/description of what control means. To do that, one can divide reality in two sections: the tangible and the intangible.

If negotiation must occur having these elements, good or bads into account, then what is feasible to represent?

This work will pursue the representation exercise by considering the conceptual and less conceptual elements that may constitute the resolution process of a conflict through negotiation. It will then, show a partial view of what an intractable situation might be - that is the point in which tractability finds a way: this work, again, stands for the negotiation agreement as the best option to resolve a conflict. But it also understands it may fail.

The Model

In order to formalize a negotiation process a dynamic model is build under the following assumptions:

1. Main variables that lead actors to negotiate or not are Trust and Willingness to negotiate. These two variables are the controllers of the acts of two actors. Acts of two actors have an effect on trust and on willingness to negotiate. These acts can be positive or negative. Trust and willingness to negotiate are interpreted as accumulations that have rates of change. Trust is a variable that can increase or decrease but it takes some time, there is inertia unless the acts of the other are strong and negative enough to provoke a sudden change in the level of trust in the other.

Dynamic hypothesis

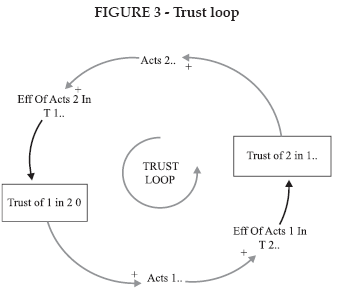

The causal diagram illustrated in figure 1 portrays the dynamic hypothesis for the model. The boxes represent the state variables of the system, which means the variables that accumulates through time. The structure is composed of two main feedback loops: Willingness loop (figure 2) and Trust loop (figure 3). Both structures are driven by the variables Acts of 1 or 2.

In the first loop the variable Acts of actor 2 has an effect on willingness to negotiate of actor 2. The effect is a linear function of Acts of 2, of positive slope which has negative and positive sections. Negative values of Acts 2 represent violent actions of 2 and positive values represent peace actions. The relation between the effect and willingness to negotiate of actor 1 has two possibilities: positive or negative, according the function explained above. It means that the stock could increase or decrease according the character of acts of actor 2. In turn, Willingness to negotiate of 1 has a direct positive relation with Acts of 1 which has a positive relation with an Effect on willingness to negotiate of 2. This effect is also a linear function with positive and negative dominions that affects the stock of willingness to negotiate of 2 which in turn has a direct positive relation with Acts of 2. In this way the feedback is closed. Due to the possibility of taking positive or negative values of the effect functions the loop could be positive or a reinforcing loop or a negative or balancing loop. It implies that this loop could balance or keep in certain state of equilibrium the system if the loop is negative or can generate exponential behaviours of Acts and willingness to negotiate of both actors.

Regarding the Trust loop (figure 3) , it works in a similar way but now the state variables are Trust of 2 in 1 and Trust of 1 in 2, and they also influence the actions of 1 and 2 (Acts 1 and Acts 2). This feedback loop could be also positive or negative according the character of acts 1 and 2. This proposed structure of two main nested feedback loops that could be either reinforcing or balancing through time generates an important degree of behavioural complexity.

Behaviour of the system

It is possible to generate different simulated scenarios depending on initial values of state variables (Willingness to negotiate and Trust) and a possibility of a sudden violent attack that could be done by one of the actors in a given moment. Table 1 shows the parameters for such scenarios. Violent attack is included in the model as a parameter that is activated when the value of the stock of trust of 2 in 1 is positive. Once this condition is fulfilled in the system, the value of acts 1 is negative, representing a violent attack. The intensity of such an attack could be adjusted for each scenario in a range of values from -10 to 10, where negative values represent violent actions against 2 and positive values mean positive actions which demonstrate a willingness to remain peaceful.

All the scenarios in Table 1 have an initial positive value of 0.5 in Trust of 1 in 2, the same for Trust of 2 in 1 except scenario 2, in which the initial value is negative (-0.5). For the variable Willingness to negotiate the initial value for all the simulations was a positive value of 1. It is necessary to say that the experiments reported in this paper still are not an exhaustive exploration of the model; the most relevant runs have been chosen for the present discussion.

Scenario 1

A peaceful world

The scenario 1, portrayed in figure 4, is the product of an initial situation in which initial values of trust and willingness to negotiate are positive which permits that trust and willingness loops function as negative or balancing loops. Such feedback loops take the system to a stable equilibrium of positive acts and positive trust and willingness to negotiate

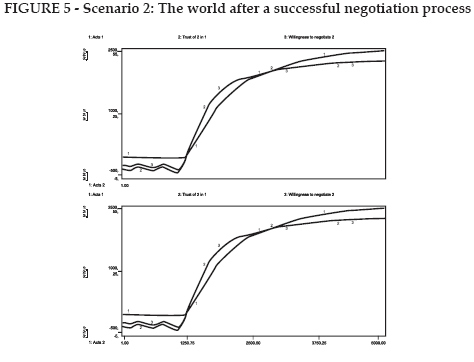

Scenario 2

The world after a successful negotiation process

In this scenario actor 2 starts with a negative value of trust of actor 2 in actor 1. During the first 1200 units of time an oscillatory pattern is shown with acts of 1 and 2 oscillating between negative and positive values which generates oscillations also in trust and willingness to negotiate of 1 and 2 as shown in figure 6. At the end of this period there is a coincidence of high levels of trust and willingness to negotiate of both actors, both variables are in phase, in this moment the main feedback loops become strongly negative and again pull up the system to a stable peace equilibrium state (figure 5).

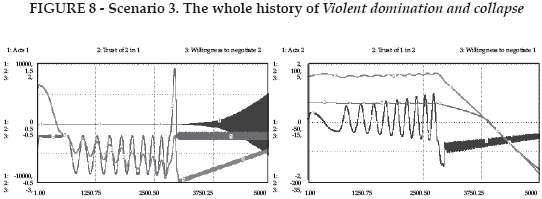

Scenario 3

Violent domination and collapse

In this experiment a violent attack of 1 is activated when trust of 2 is positive, and trough time as soon as trust of 2 is bigger than 0.3 another violent attack is launched by 1. Figure 7 shows in detail the behavior of Acts , at 30 units of time approximately Acts 1 take suddenly a value negative. Trust and willingness of 2 decreases for the moment but increases again, but, when trust is again bigger than 0.3 another attack is committed by 1 and so on. The consequence is that willingness to negotiate of 2 starts to decrease.

In figure 8 it is possible to observe the behavior in the long run. For better understanding of the whole story, it is possible to divide the behavior in two parts: a first stable and oscillatory period and a second part of an instability period, in which acts of 1 show an increasing oscillation pattern whose effect in 2 is a general increase in willingness to negotiate of 2 and a slow decreasing of negative acts of 2. In this second part trust and willingness to negotiate of actor 1 decrease. This situation represents a collapse of the system because actor 2 is suffering violent attacks of increased strength which force actor 2 to try to negotiate, while actor 1 decreases his willingness to negotiate because of its lack of relevance: actor 1 is controlling the situation.

Scenario 4

A violent world of instability

When the violent attack of actor 1 is very strong, initially there is a positive willingness to negotiate of 2 but after sometime its willingness decreases and now is actor 2 who takes revenge and responds with acts more violent and strong through time. This behavior forces actor 1 to increase its willingness to negotiate while its trust in 2 oscillates but remains low. As a result this scenario yields a world of oscillations and an increasing revenge of actor 2 with scarce possibilities for actors 1 and 2 to coincide in some moment with high degrees of willingness to negotiate. What happens, regarding the structure of the system, is that the main feedback loops are of reinforcing character of positive loops that always try to take out the system from any equilibrium state.

Through this brief exploration of this simple model it is possible to observe how initial conditions in a conflict situation or in a negotiation process can determine the following course of a confrontational story. This path dependence pattern is explained by the existence of positive feedback loops which could dominate the system early in time. These positive loops could be triggered by surprising events which constitute shocks to the system; in this case we have modeled a sudden violent attack, and the experiments have shown its capacity to take the system away from a peaceful equilibrium. When actors allow balancing feedback loops to dominate the system, it goes towards a stable equilibrium state of high willingness to negotiate, trust and positive acts of both actors. Further experimentation and exploration of the model could give insights about how to keep negative or balancing feedback loops strong enough to recuperate a stable peaceful equilibrium state despite surprising violent events. Trust, if affected, starts to suffer variable ups and downs. But as stated not enough, armed conflicts do not suffer anything: it is people who do.

3 Crocker, C.; Hampson, F. & All, P. (eds.) (2004), Taming Intractable Conflicts. Mediation in the Hardest Cases, Washigton, USIP; Kriesberg, L. (2003), Constructive Conflicts. From Escalation to Resolution, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Maryland; Mitchell, C. (1997), "Intractable Conflicts: Keys to Treatment", Gernika Gogoratuz, Work Paper no. 10, Gernika.

4 Keane, (1996, May.-Ago), "Transformacoes estruturais da esfera pública" en Comunicacao e Política Vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 6-28.

5 Galtung, J. (1993), Peace Studies: Peace and Conflict; Development and Civilization, class notes, author's manuscript, Schlaining, Austria.

6 Höglund, K. (2004), Negotiations amidst Violence. Explaining Violence-Induced Crisis in, Peace Negotiation Processes, Interim Report IR-04-002, International Institute for Applied Systems, Austria.

7 Putnam, L. & Wondolleck, J. (2003), "Intractability: Definitions, Dimensions and Distinctions" in Making Sense of Intractable Environmental Conflicts. Concepts and Cases, Washington, Covelo, London, Island Press.

8 Bar-Yam, Y. (2007), Complexity of Military Conflict: Multiscale Complex Systems Análisis of Litoral Warfare, [en línea], disponible en http://necsi.org/faculty/bar-yam.html, p.1 New England Complex Siystems Institute, last consulted February 2007.

9 Ibíd.

10 Luhmann, N. (2002), Introducción a la teoría de sistemas. Lecciones publicadas por Javier Torres Nafarrete, México, Universidad Iberoamericana.

11 Bar-Yam, Y., op. cit.

12 Salamanca, M.; Castillo, D. y Stover, M. (2006), Pilot Study for the Project "A Participative Strategy for the Management of Conflict in Colombia's Sumapaz Zone", Universidad Javeriana, Columbia University.

13 Luhmann, N. (2002), Introducción a la teoría de sistemas. Lecciones publicadas por Javier Torres Nafarrete, México, Universidad Iberoamericana; (1995), Social Systems, Stanford, Stanford University Press (from the original in German: (1984), Soziale Systeme: Grundriss einer allgemeinen Theorie.

14 Galtung, J. (1993), Peace Studies: Peace and Conflict; Development and Civilization, class notes, author's manuscript, Schlaining, Austria.

15 Salamanca, M. (2000), "Democracia y resolución de conflictos políticos" en Papel Político, num. 11; Valenzuela, P. (1996), "El proceso de terminación de conflictos violentos: un marco de análisis con aplicación al caso colombiano" en Papel Político, num. 3; (1998), "Intermediación y resolución de conflictos violentos" en Papel Político, num. 8.

16 Feldman, A. (1991), Formations of Violence- The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland, Chicago, Londres, University of Chicago Press; Apter, D. (1977), "Political Violence in Analytical Perspective" in Apter, D. (ed.), The Legitimization of Violence, New York, New York university Press, pp. 1 - 32. [ Links ]

17 Mitchell, C. (1997), "Intractable Conflicts: Keys to Treatment", Gernika Gogoratuz, Work Paper no. 10, Gernika.

18 Ostrom, E. (1990), Govrning the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge University Press; Castillo D. & Saysel A. (2005), "Simulation of common pool resource field Experiments" in Ecological Economics, 55, pp. 420-436.

19 Hardin, G. (1968), "The Tragedy of the Commons" en Science, num. 162, pp. 1243-1248; Ostrom, E. (1990), Govrning the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge University Press; (1988), "A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action" in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, num. 1, pp.1-22; (2006), Rules, Games & Common Pool Resources, Michigan University Press.

20 Ostrom, E. (2006), Rules, Games & Common Pool Resources, Michigan University Press.

21 Ostrom, E. (2005), Understanding Institutional Diversity, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

22 Garzón et al., (2005).

23 Salamanca, M. (2000), "Democracia y resolución de conflictos políticos" en Papel Político, num. 11; (2005), "La violencia representada: bases para la construcción de modelos dinámicos" en Papel Político, num. 17, pp. 33 - 65; (2006), "La afectación de la vida cotidiana por procesos de violencia política. El caso de Colombia", Anuario de Humanos, Instituto Pedro Arrupe Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao.

References

Apter, D. (1977), "Political Violence in Analytical Perspective" in Apter, D. (ed.), The Legitimization of Violence, New York, New York university Press, pp. 1 - 32.

Bar-Yam, Y. (2007), Complexity of Military Conflict: Multiscale Complex Systems Análisis of Litoral Warfare, [en línea], disponible en http://necsi.org/faculty/bar-yam.html, p.1 New England Complex Siystems Institute, last consulted February 2007. [ Links ]

Castillo D. & Saysel A. (2005), "Simulation of common pool resource field Experiments" in Ecological Economics, 55, pp. 420-436. [ Links ]

Crocker, C.; Hampson, F. & All, P. (eds.) (2004), Taming Intractable Conflicts. Mediation in the Hardest Cases, Washigton, USIP. [ Links ]

_______. (2005), Grasping the Nettle. Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict, Washington USIP. [ Links ]

Feldman, A. (1991), Formations of Violence- The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland, Chicago, Londres, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. (1993), Peace Studies: Peace and Conflict; Development and Civilization, class notes, author's manuscript, Schlaining, Austria. [ Links ]

Harbom, L. (ed.) (2006), States in Armed Conflict 2005, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Upsala, Suecia. [ Links ]

Hardin, G. (1968), "The Tragedy of the Commons" en Science, num. 162, pp. 1243- 1248. [ Links ]

Höglund, K. (2004), Negotiations amidst Violence. Explaining Violence-Induced Crisis in, Peace Negotiation Processes, Interim Report IR-04-002, International Institute for Applied Systems, Austria. [ Links ]

Keane, J. (2006, May.-Ago.), "Transformacoes estruturais da esfera pública" en Comunicacao e Política, Vol. 3, num. 2, pp. 6-28. [ Links ]

Keohane, R. & Ostrom, E. (1995), Local Commons and Global Interdependence, London, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Kriesberg, L. (2003), Constructive Conflicts. From Escalation to Resolution, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Maryland. [ Links ]

Licklider, R. (2005), "Comparative Studies of Long Wars" in. Crocker, Ch. A; Hampson, F. O. & Aall, P., Grasping the Nettle. Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict, Washington D.C., United States Institute of Peace. [ Links ]

Luhmann, N. (2002), Introducción a la teoría de sistemas. Lecciones publicadas por Javier Torres Nafarrete, México, Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

_______. (1995), Social Systems, Stanford, Stanford University Press (from the original in German: (1984), Soziale Systeme: Grundriss einer allgemeinen Theorie. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (1997), "Intractable Conflicts: Keys to Treatment", Gernika Gogoratuz, Work Paper no. 10, Gernika. [ Links ]

Ostrom, E. (1990), Govrning the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University, 1999. . [ Links ]

_______. (1988), "A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action" in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, num. 1, pp.1-22. [ Links ]

_______. (2005), Understanding Institutional Diversity, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

_______.(2006), Rules, Games & Common Pool Resources, Michigan, Michigan University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Putnam, L. & Wondolleck, J. (2003), "Intractability: Definitions, Dimensions and Distinctions" in Making Sense of Intractable Environmental Conflicts. Concepts and Cases, Washington, Covelo, London, Island Press. [ Links ]

Salamanca, M. (2000), "Democracia y resolución de conflictos políticos" en Papel Político, num. 11, pp 67-92. [ Links ]

_______. (2005), "La violencia representada: bases para la construcción de modelos dinámicos" en Papel Político, num. 17, pp. 33 - 65. [ Links ]

Salamanca M.; (2006), "La afectación de la vida cotidiana por procesos de violencia política. El caso de Colombia", Anuario de Humanos, Instituto Pedro Arrupe Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao. [ Links ]

_______. (2007), Violencia política y modelos dinámicos: un estudio sobre el caso colombiano, Bilbao, Instituto Pedro Arrupe Universidad de Deusto, San Sebastián, Diputación de Guipúzcoa. [ Links ]

Salamanca, M.; Castillo, D. y Stover, M. (2006), Pilot Study for the Project "A Participative Strategy for the Management of Conflict in Colombia's Sumapaz Zone", Universidad Javeriana, Columbia University. [ Links ]

Sterman, J. (2000), Business Dynamics - Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, Boston, Irwin McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, P. (1996), "El proceso de terminación de conflictos violentos: un marco de análisis con aplicación al caso colombiano" en Papel Político, num. 3, pp. 53-71. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, P (1998), "Intermediación y resolución de conflictos violentos" en Papel Político, num. 8, pp. 7-29. [ Links ]

Wallensteen, P. (2007), Understanding Conflict Resolution, London, Sage. [ Links ]