Interpersonal violence (IV) refers to the intentional use of force or power by one person against another person or group of people. It includes physical, sexual or psychological violence, in any family or community context and can affect people of any age or demographic (Mercy et al., 2017). The World Health Organisation (2022) recognises that IV includes violence towards people of specific age groups (child maltreatment, youth violence, or abuse of older people) as well as violence directed to any member of society (intimate partner violence, sexual violence or institutional violence). However, children and adolescents have received more attention in research due to the negative enduring effects of IV inflicted during childhood (Centres for Disease Prevention and Control, 2016; Guerra & Arredondo, 2017). In this population, IV includes physical, sexual or emotional abuse or neglect that generates harm (or potential for harm) in people under the age of 18 (Centres for Disease Prevention and Control, 2016). It includes abuse at school, bullying, severe intimidation, exposure to domestic violence and violence mediated by technology, such as cyberbullying or online sexual abuse (D’Andrea et al., 2012; Maurya et al., 2022; Quayle & Sinclair, 2012).

A recent report by UNICEF (Fry et al., 2021) estimates that around 34% (58 million) of children and adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean have experienced at least one form of IV in the last year, particularly severe physical or emotional violence, sexual violence, bullying or having witnessed violent events. In Mexico, 27.7% of 3,005 adolescents reported one form of victimisation, 28.2% reported two or three, and 13% reported four or more, the most frequent being physical abuse by caregivers, witnessing physical fights at home, assaults, and threats with weapons (Orozco et al., 2008). In El Salvador, where 31.1% of 1,296 youths reported experiencing five or more trauma types, the most frequent form of IV is witnessing community violence (Stewart et al., 2021). In Colombia, 21.5% of 1,462 adolescents reported experiencing three or more different forms of victimisation over their lifetime (Caballero-Domínguez et al., 2022). In Chile, 21.3% of a representative sample of 19,648 children and youths reported between one and three different forms of victimisation in their lives, 24.6% reported between four and six and 45.5% reported seven or more forms of victimisation, the most frequent being conventional crimes (assault, vandalism, robberies) and victimisation by peers and caregivers (Pinto-Cortez, et al., 2022).

IV in childhood and adolescence is different from other types of potentially traumatic events (e.g., natural disasters, illnesses, accidents) because the source of the episode is another human being, generally someone with a caregiving or protective role towards the child (Centres for Disease Prevention and Control, 2016). For this reason, IV has a relational component that must be considered when analysing its consequences and the treatment thereof.

There is a consensus that IV has serious consequences for children and adolescents, which can affect their well-being and adaptation in the short and long term, and has socio-emotional impacts that can last into adulthood (Agorastos, et al., 2014; Fry et al., 2018; Maglione et al., 2018). It is common to observe symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), behaviour problems, social adaptation problems and aggressive behaviour in victims (Álvarez-Lister et al., 2014; Ford & Delker, 2018; Játiva & Cerezo, 2014; Norman et al., 2012).

Evidence-based psychological treatment refers to the application of the scientific method to empirically demonstrate the effectiveness of different modalities of psychotherapy for treating specific disorders (Moriana & Martínez, 2011). In the case of IV - due to the complexity of the symptoms- a phase-based approach to psychological treatment has been recommended (Cloitre et al., 2012). The first phase focuses on the stabilisation of symptoms through psychoeducation, the delivery of coping strategies and emotional regulation. The second phase focuses on the reprocessing of traumatic memories; and the third phase focuses on the future, giving a new meaning to the traumatic experience and resuming a normal course of life (Cloitre et al., 2011; Herman, 1997). A very small evidence base suggests phase-based approaches may be useful for children and adolescents, but this area of empirical enquiry is in its infancy (Darby et al., 2023).

Internationally, the interventions that have shown effectiveness in the treatment of IV-related trauma symptoms have a structure compatible with the phase-based approach. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT; Cohen et al. 2006) has the strongest evidence base. TF-CBT is based on the principles of the cognitive-behavioural model and includes phases of psychoeducation, relaxation, expression and regulation of emotions, coping strategies and cognitive processing, as well as the creation of a trauma narrative that allows for reconceptualisation of the experience. This therapy has received empirical support in multiple international studies (Gillies et al., 2013; Konanur et al., 2015; Morina et al., 2016). A recent systematic review demonstrates that other phase-based treatments including Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) for PTSD, Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR), and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) are all effective in reducing post-traumatic symptoms and demonstrate superiority to single-phase exposure-based treatments (Darby et al., 2023). Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) is also evidenced as efficacious (Dorsey et al., 2017).

Despite the evidence that exists at an international level, various authors note the absence of research in Latin America. Instead, interventions validated in Europe and the United States are imported without adequate cultural adaptation (Bernal & Rodríguez-Soto, 2012; Martínez-Taboas, 2014; Vera-Villarroel & Mustaca, 2006). This reflects a more general absence of research on the effectiveness of treating the consequences of IV in Latin America. For example, Guerra and Arredondo’s (2017) systematic review in Chile evidenced the scarcity of relevant research as well as serious methodological limitations within the extant evidence. They identified a tendency to publish recommendations and opinions based on the experience of therapists rather than systematically gathered empirical evidence. Furthermore, it is possible that across Latin America there exists more evidence, but it isn’t visible to the international scientific community. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have allowed for a significant advance in the reliability of recommendations provided for empirically validated treatments. However, there is a tendency to exclude papers written in languages other than English. For example, in an otherwise comprehensive meta-analysis of psychological treatments for PTSD, the 135 studies were exclusively published in English (Gutermann et al., 2016).

Whatever the reason, the consequence is little knowledge regarding effective treatments for the psychological sequelae of IV in Latin America leading to lack of confidence and investment in evidence-based treatment. We need culturally adapted psychotherapy models, that have proven effectiveness within a given cultural context, while recognising the risk of applying ineffective or even harmful interventions in a given context (Christopher et al., 2014; de Arellano et al., 2012; Murray & Skavenski, 2012). These adaptations should consider the culture, context and language in order to contribute to the generation of an effective psychotherapy but contextualised to the cultural meanings of the young person’s environment (Bernal et al., 2009; Guerra et al., 2022).

In Latin America there is an urgent need to advance empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of psychological treatments for the consequences of IV, not only because of the high frequency of this phenomenon, but also because it is estimated that a high proportion of people requiring psychological care do not currently receive treatment. For example, in the case of PTSD, the Panaméricana de la Salud (2017) estimates that 65.4% of patients (including adults and children) do not receive the necessary treatment. Reliable information on empirically validated treatments will allow services and clinicians to deliver treatment efficiently and effectively. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review is to identify which psychotherapy models/modalities have been shown to be effective in Latin America to treat the psychological consequences of interpersonal violence suffered in childhood or adolescence.

Method

Protocol and registration

Prior to carrying out the systematic review, a search protocol was prepared, which was published under ID CRD42022308156 in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (Guerra, Meza et al., 2022).

Search strategy

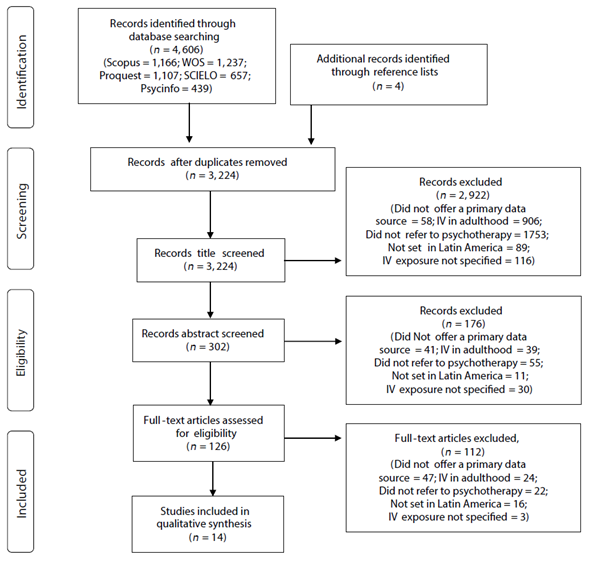

A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Möher et al., 2009). The complete search was finished on 06/03/2023 using the following databases: Scopus, WOS, Proquest Latin America & Iberia Database, SciELO, PsycINFO. References of the selected papers were screened against the inclusion criteria as a secondary search strategy.

The search was conducted twice first in English and then in Spanish with the following search words in the title, abstract and keywords: (Abuse OR Trauma* OR Violence OR Victim* OR Maltreatment) AND (treatment OR intervention OR psychotherapy OR Program OR Therapy) AND (“Latin America” OR Caribe OR “Central America” OR “Sud America” OR Argentina OR Belize OR Bolivia OR Brazil OR Chile OR Colombia OR “Costa Rica” OR Cuba OR Ecuador OR “El Salvador” OR Guatemala OR Guyana OR Haiti OR Honduras OR Jamaica OR Mexico OR Nicaragua OR Panamá OR Paraguay OR Perú OR “Puerto Rico” OR “Dominican Republic” OR Surinam OR “Trinidad and Tobago” OR Uruguay OR Venezuela). In Spanish: (Abuso OR Trauma* OR Violencia OR Victim* OR Violación OR Maltrato) AND (tratamiento OR Intervención OR psicoterapia OR Programa OR Terapia) And (“Latin America” OR Caribe OR “Central America” OR “Sud America” OR Argentina OR Belize OR Bolivia OR Brazil OR Chile OR Colombia OR “Costa Rica” OR Cuba OR Ecuador OR “El Salvador” OR Guatemala OR Guyana OR Haiti OR Honduras OR Jamaica OR México OR Nicaragua OR Panamá OR Paraguay OR Perú OR “Puerto Rico” OR “Dominican Re public” OR Surinam OR “Trinidad and Tobago” OR Uruguay OR Venezuela). Search dates were fixed from January 2000 to March 2023 since we are interested in knowing the latest evidence in the Latin-American context. Papers could be published in peer-reviewed journals, in any language.

This systematic review aspired to access the evidence of the effectiveness of psychotherapy for treating the psychological consequences of IV suffered during childhood in a Latin American context. Given that these consequences can persist into adulthood, this review includes interventions for adults maltreated in childhood. The inclusion criteria were specified accordingly using PICOS criteria.

Population. People of any age who had suffered interpersonal violence in their childhood or adolescence before the age of 18 were included. IV could be identified through self-report, evaluation within the trial or by referral pathway (e.g., involvement of child protection services) In mixed child and adult samples, the mean age of exposure to IV had to fall below 18 years of age or more than 75% of the sample had to be under 18 years of age, depending on available information. In mixed samples of victims of IV and other types of traumatic experiences, at least 50% of the sample should be victims of IV. Research describing the treatment of adults who were exposed to interpersonal violence after the age of 18 was excluded.

Since the focus of this paper is to know the state of psychotherapy within the Latin American context rather than the Latin American diaspora, only studies describing data collection in a Latin American country were included. Studies describing interventions with Latin American migrants outside of the Latin American context were therefore excluded. We have included in this search all the countries of the American continent with the exception of Canada and the United States (commonly known as Latin America and the Caribbean, hereafter referred to as Latin America).

Intervention. All psychological interventions for treating the consequences of interpersonal violence were eligible for inclusion. This was not restricted to PTSD. Interventions had to be structured with well-defined objectives, such as cognitive and cognitive behavioural therapies, interpersonal psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapies, and art therapy. Any delivery method was eligible for inclusion: group, individual, face to face, online. Drug trials without a psychotherapy component were excluded.

Control. a control group was not required for inclusion but was accounted for in the quality appraisal.

Outcomes. Systematic evaluation of the intervention was required. To be selected, quantitative studies had to include a validated measure of psychological symptoms (e.g., PTSD, depression, anxiety) or other cognitive, behavioural or emotional variables (e.g., self-efficacy, coping, wellbeing). Qualitative studies had to provide an a priori outcome target and assess this within an explicit qualitative analysis framework.

Study design. In this review we include papers with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method research designs including single-group pre-post design, randomised or non-randomised control trials and single-n and case studies. This open criterion reflects the nascent state of the evidence base in Latin America (Guerra & Arredondo, 2017). Opinion pieces, books, book chapters, book reviews, theoretical analyses, systematic reviews, or any article that did not offer a primary data source or had not been published in a peer-reviewed source were excluded.

Search results and data extraction

Given the large number of papers found in a preliminary search (n = 17,193), filters by subject area were used in the databases that allowed it. Hence, in WOS, Scopus and Scielo only papers in the field of psychology were included. These papers were downloaded into EndNote and duplicates were removed. The selection of the final papers was carried out in three steps. First, the titles of the identified studies were examined, then the abstract and finally the full text. This process was carried out by two independent reviewers. Any difference between the reviewers was resolved by mutual agreement, with the mediation of a third reviewer as needed. Finally, the references of the selected papers were reviewed in order to search for new papers that met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

Quality assessment

Risk of bias was tested using the RTI item bank for observational studies (Viswanathan & Berkman, 2011). The first 13 items were used, removing items 10 and 11: adverse events and believability), and adding three supplementary items from the longer bank relating to statistical analysis (sample size, intention-to-treat analyses, and appropriateness of statistical methods), totalling 14 items. This tool is designed to work with various study designs from single n studies to randomised controlled trials, with items rated as non-applicable for certain designs. The scale is not designed to produce a total score as studies are rated on different numbers of items depending on design, but a mean score can be derived by rating zero (criteria not met), one (criteria partially met) or two (criteria fully met). This produced an overall rating of low, medium or high risk of bias.

Analysis plan

The data synthesis was carried out following the PICOS model (Methley et al., 2014). Descriptive Tables were prepared that include information on the participants (number, age, gender, type of interpersonal violence suffered), the intervention (description of the model of psychotherapy applied), the type of control groups used, the outcomes (type of outcome, instrument or technique used) and the study design.

Cohen’s d was computed for the difference between the pre- and post-intervention measures, when the authors reported the n, mean and standard deviation. The formula used was: M1-M2/√((SD12 + SD22)/2). It was not possible in single case analyses. Cohen’s d values less than .20 indicate the non-existence of an effect; values between .21 and .49 refer to a small effect; values between .50 and .70 indicate a moderate effect; and values greater than .80 indicate a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

Results

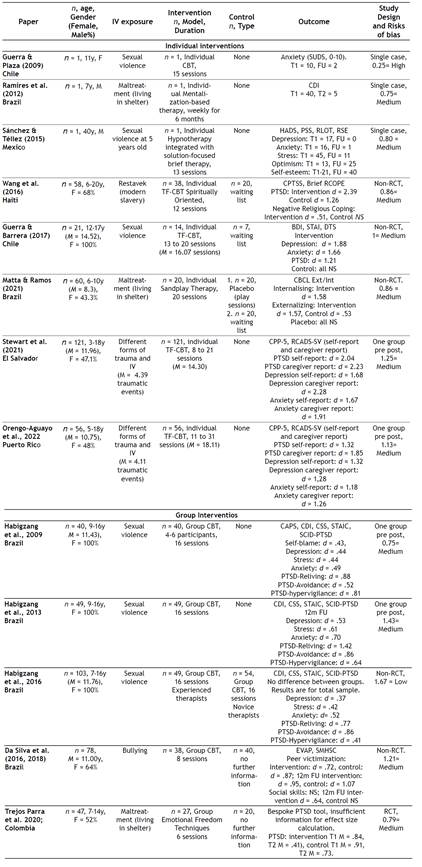

The search yielded 14 papers related to 13 studies and one follow-up. Six studies were carried out in Brazil, two in Chile, one in Mexico, one in El Salvador, one in Puerto Rico, one in Haiti and one in Colombia (see Table 1 for study details).

Table 1 Study characteristics and outcomes

CBT = Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; SUDS = Subjective Units of Distress Scale, T1 = Time 1/Baseline, FU = Follow-up, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory, T2 = Time 2/treatment completion, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, RLOT = Revised Life Orientation Test, RSE = Rosenberg Self-esteem scale, TF-CBT = Trauma focused CBT, W/L = Waiting list; CPSS = Child PTSD Symptom Scale, Brief RCOPE = Brief Religious Coping Scale, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, STAI = Stait-Trait Anxiety Inventory, DTS = Davidson Trauma Scale, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, CBCL = Cognitive Behaviour Check List,CPSS-5 = Child PTSD symptoms Scale for DSM-5; RCADS-SV = Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale- Short Version; CAPS = Children’s attributions and perceptions scale), CSI = Children’s stress inventory), SCID-PTSD = Structured Clinical Interview based on DSM-IV for assessing PTSD), EVAP = Aggression and Peer Victimisation Scale, SMHSC = Multimedia System of Social Skills for Children

Population

Sample sizes varied from n = 1-121. All studies worked with samples of children and adolescents, except one which worked with an adult who suffered IV in childhood (Sánchez & Téllez, 2015). Six studies described psychotherapeutic interventions to treat the consequences of sexual violence, three dealt with the consequences of maltreatment of children living in shelters, two involved treatments of victims of different forms of trauma, one refers to treatment for the consequences of bullying, and one to the treatment of the consequences of restavek, a form of modern child slavery.

Interventions

Eight studies refer to individual interventions and five studies refer to group interventions (Table 1 shows first individual and then group interventions). Among the individual interventions, five studies described cognitive behavioural interventions and three described models with psychoanalytic influence: mentalisation, sandplay therapy and a combination of hypnotherapy and solution-focused brief therapy. All eight individual interventions varied between eight sessions (approximately four months) and 31 sessions (approximately seven months and two weeks).

Among the group interventions, four studies describe cognitive behavioural interventions and one describes an intervention based on emotional release techniques, which integrates acupuncture-type body stimulation with recreational plastic expression type art therapy. Interventions lasted eight to 16 sessions.

Control

Only three of the eight individual studies had a control group, but in all cases, these were waiting list controls rather than an active control condition, and were non-ran domised (Guerra & Barrera, 2017; Matta & Ramos, 2021; Wang et al., 2016). Additionally, the three studies that included a control group had a relatively small sample (between 21 and 60 participants).

Three of the five studies related to group interventions included a control (da Silva et al., 2016; Habigzang et al., 2016; Trejos- Parra et al., 2020) but only one was randomised and in one study the control group was the very intervention itself but delivered by novice therapists.

Outcomes

Three studies described single-n studies with clinically significant improvements following Cognitive behavioural therapy (Guerra & Plaza, 2009), Mentalisation based therapy (Ramires et al., 2012) and Hypnotherapy (Sánchez & Téllez, 2015). The other five studies regarding individual TF-CBT (Guerra & Barrera, 2017; Orengo-Aguayo et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2016), and sandplay Therapy (Matta & Ramos, 2021) all found medium to large effect sizes for outcomes including PTSD, depression and anxiety, but two of them did not use a control group and three used a nonrandomised passive control condition.

In two studies the waiting list control group also showed significant improvements in externalising symptoms, with a medium effect (Matta & Ramos, 2021), and PTSD symptoms, with a large effect (Wang et al., 2016).

Group cognitive-behavioural interventions showed effectiveness in three studies using the same intervention model with three equivalent samples of victims of sexual abuse, reducing self-blame beliefs, symptoms of depression, stress, anxiety, PTSD, after the intervention (Habigzang et al., 2009) and in a follow-up after 12 months (Habigzang et al., 2013). For the most part, effect sizes were moderate to high. Furthermore, the intervention was equally effective when delivered by experienced therapists or novice therapists (Habigzang et al., 2016). Another group cognitive-behavioural intervention to victims of bullying found reductions in victimisation (da Silva et al. al., 2016), inclusive in the follow-up. However, the control group achieved the same outcomes. This was maintained in the 12-month follow-up (da Silva et al. al., 2018). No improvements were seen in social skills in either condition, but in the follow-up, the intervention group reported a reduction of social skills problems. Finally, in Trejos Parra et al.’s (2020) study, both the control and the interventions groups (Emotional Freedom) showed improvements in PTSD symptoms.

Study design and risk of bias

There was one randomised controlled trial (RCT), five non-RCT, four papers using a single-group pre-post design, and three case studies.

Only Habigzang et al. (2016)’s study was rated as a low risk of bias. All remaining studies were rated as having a medium or high risk of bias. Whilst case studies are inherently open to bias, the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in this sample also demonstrated medium or high risk of bias. For example, one controlled trial did not state whether allocation to conditions was randomised (da Silva, 2016, 2018). No studies reported a published study protocol or referred to adherence to or deviation from this protocol. However, Wang et al. (2016) reported their 12-week programme taking much longer for some young people and included time as a variable in their analysis.

Most studies did not consider a control group, and the ones who did used a waiting list or placebo control group (Guerra & Barrera, 2017; Matta & Ramos 2021; Wang et al. 2016) or lacked detail on what control group participants received (da Silva et al., 2016, 2018; Trejos Parra et al., 2020). Recruitment strategies and inclusion/exclusion criteria were consistently applied across intervention and control groups. In studies with control groups, the analysis did not typically include a direct comparison between intervention and control group outcomes, which was relevant given how many control groups also achieved significant improvements. Intervention x time interactions were also not tested in any study apart from Wang et al. (2016).

All studies relied on quantitative measures, and in three cases this was a single measure (Guerra & Plaza, 2009; Matta & Ramos, 2021; Trejos Parra et al., 2021). In all cases, measures were validated and where language translations were required, these followed recommended procedures for validation. Habigzang et al.’s (2009, 2013, 2016) studies stood out for including both clinician-assessed and self-report measures. The other studies only used a self-report measure.

With the exception of five papers (Habigzang et al 2013, 2016; Orengo-Aguayo et al, 2022; Stewart et al 2021; Wang et al., 2016), studies reported no attrition during the intervention, with the reported n at outcome being the same as at intake. Given the complexity of circumstances for this population this is surprising and may reflect a gap in reporting.

Finally, all studies reported medium to large effect sizes. This can be an artefact of smaller samples requiring larger effect sizes to achieve statistical significance, but some studies in this sample had substantial samples. Confounding variables were not controlled for analysis, and there is evidence this might have amplified outcomes. Wang et al. (2016), is the exception who did control for time and found time to be the principal factor in trauma symptom reduction (treatment also had an effect).

Cultural adaptations

Cultural adaptations were described in three studies including practical aspects such as conducting therapy in the young person’s home as is common in Chile (Guerra & Plaza, 2006) or personalising written materials to that country, considering cultural local values (Chile: Guerra & Barrera, 2017; Puerto Rico: Orengo-Aguayo et al., 2022; El Salvador: Stewart et al., 2021). Other adaptations responded to nation-specific service delivery models. For example, the Chilean system requires complainants to repeatedly recount the trauma narrative as part of the legal process, with high risk of revictimisation. In response, the authors extended the phase of the TF-CBT called “the trauma narrative” and instead of addressing the trauma directly, aligned it with narratives of positive events in the patient’s life (Guerra & Barrera, 2017). In Haiti, Wang et al. (2016) introduced a spiritual orientation to ensure relevance in the Haitian context. They included stories, songs, or passages of sacred texts drawn from the client’s personal religious tradition in therapy and placed a special focus in therapy on reframing trauma-related religious-themed cognitive distortions, such as the belief that God would abandon them or He would be angry if they participated in psychotherapy.

In other studies, interventions had been designed for a specific population, but ways in which they were made culturally appropriate were not explicitly labelled (Brazil; Habigzang, et al., 2009, 2013, 2016) and there are several studies that do not specify whether the intervention was created or adapted to the Latin American context or not (Brazil: Da Silva et al., 2016, 2018; Matta & Ramos, 2021; Ramires et al., 2012; Mexico: Sánchez & Téllez, 2015; Colombia: Trejos Parra, et al. 2020).

Discussion

The objective of this research was to identify which psychotherapy models/modalities have been shown to be effective in Latin America to treat the psychological consequences of interpersonal violence suffered in childhood or adolescence. Despite broad inclusion criteria, including single-case designs through to RCTs, only 13 studies were found related to Latin America.

As reported in a previous review (Guerra & Arredondo, 2017), more opinion articles or clinical recommendations are published than empirical studies. In this review, of the 126 full texts analysed, 47 (37%) were excluded for not offering a primary data source. These papers provide valuable information that reflect the experience of clinical psychologists on the continent, however, systematically gathered empirical evidence is needed.

This deficit is reflected in other areas and may result from a lack of training in evidence-based psychotherapies and their evaluation as well as a lack of policies, funds, and infrastructure to carry out high-impact research (Balán, 2012; Moncada & Kühne, 2003; Reveiz et al., 2013). In fact, only six of the studies in this review were funded: four for one Latin American Country (Brazil: da Silva et al., 2016, 2018; Habigzang et al., 2009; Matta & Ramos, 2021) and two for the United States (Orengo-Aguayo, et al., 2020; Stewart et al. (2021). In addition, research is being carried out by a small group of investigators, with three research groups responsible for eight of the studies in the review.

Latin America needs its own evidence base to allow for proper consideration of the influence of cultural factors (e.g., machismo, religiosity, family values, relationship with parents, normalisation of gender violence) on intervention effectiveness (de Arellano et al., 2012; Orengo-Aguayo, et al., 2020), as well as how psychotherapeutic interventions are integrated with the wider response to IV in Latin American and Caribbean countries (e.g., legal proceedings, health examinations), in order to prevent secondary victimisation (Berrios et al., 2019; Guerra, & Barrera, 2017).

This review found results with specific relevance to the Latin American Context. First, five (38.46%) studies analysed the effects of group therapy which is relevant given the cultural characteristics of Latin America, with a greater tendency towards collectivism than individualism (Triandis, 2015). Group interventions could be a good alternative, making a more efficient use of resources in a context of high incidence of IV and considering the reported care gap (Fry et al., 2021; Pan American Health Organisation, 2017). Although group therapies can be a useful model in Latin America, measures must be taken to ensure confidentiality within the group, and avoid overexposure of participants and vicarious victimisation (Guerra, Toro et al., 2022).

Second, cognitive behavioural interventions (including TF-CBT) dominate the evidence base (9 of 13 studies or 69.23%), reflecting the abundant evidence in favour of this model of intervention in Latin America. This is coherent with the evidence from other countries, including the United States (de Arellano et al., 2014), Africa (McMullen et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2013; O’Callaghan et al. 2013), and with Latin American adolescents residing in the United States (Patel et al., 2022). However, regardless of model or delivery, all studies found clinically and/or statistically significant changes.

However, we must be cautious since the evidence is not conclusive, and we found substantial risk of bias in the published articles. Most studies did not use a control group, and those that did, mostly did not report which intervention the control group received or used a passive control. It is necessary to advance more robust designs (e.g., RCTs) with the use of active control groups (e.g., receiving treatment as usual) that better guarantee the wellbeing of the participants (Freedland et al., 2011). No studies reported publication of a protocol, making it impossible to judge whether trials were reporting on the outcomes they originally intended. Publication of a protocol in advance of trials would help to reduce bias and the adoption of recognised reporting standards by journals would facilitate accurate re-porting. Lower quality can also be an indication of an evidence base still in its infancy, with trials being developed on an experimental basis. Only one study described itself as a pilot (Guerra & Barrera, 2017) but with the exception of Habigzang et al.’s evolving series of studies, all the trials reported appeared to be first-time deliveries. In this context, small samples and a lack of randomisation are appropriate as a first stage towards a full RCT. However, information about strategies to maintain fidelity to the model, measures of acceptability and feasibility (including attrition), and sample size estimates matched to the analysis plan all form part of these preliminary steps, and these were absent with the exception of Orengo-Aguayo et al. (2022) and Stewart et al. (2021).

Globally, the target population can be difficult to access and treat due to complicated and dynamic domestic arrangements, lack of effective formal and informal support in the child’s network, and concurrent legal proceedings. The impact of the child’s trauma experience on their behaviour and neurodevelopment can also impair their ability to engage effectively with a therapeutic process. Some of the studies in this trial managed to recruit children in highly complex environments, and information about attrition (e.g., Wang et al., 2016) provides important insight into the reality of service delivery in specific contexts that are essential to novel psychological intervention moving beyond the research setting and into common practice. Researchers should be encouraged towards greater transparency regarding their research practice and adhering to reporting guidance facilitates this.

Conclusions, limitations and challenges for the future

The results of this study show that in Latin America there is still little evidence regarding the effectiveness of psychotherapy models and modalities to treat the consequences of IV suffered in childhood and adolescence. Although there is extensive clinical experience on the continent, this has not translated into empirical evidence, which leaves a task at different levels.

Greater development of evidence-based psychotherapy is required, in order to enhance the professional practice of psychotherapy with empirical support, considering the context and culture of the patient (American Psychological Association, 2005). More studies are needed as well as for these to meet quality standards for conduct and reporting through the use of more complex designs (such as RCTs) and with larger and more representative samples of the local population.

In Latin America there are barriers to carrying out research on the effectiveness of interventions, among which the lack of economic resources to conduct research and the lack of training in evidence-based psychotherapies stand out (Bernal & Rodríguez-Soto, 2012; Martínez-Taboas, 2014; Vera-Villarroel & Mustaca, 2006). The research challenge is considerable, entailing the development of protocols, the evaluation of feasibility, the acceptability and scalability of effective interventions and the implementation in practice through training and supervision (Balán, 2012; Moncada & Kühne, 2003; Reveiz et al., 2013). To do all of this requires the collaboration of different stakeholders on a national and international level. A joint effort to support more high-quality research is needed between funding bodies, universities and research teams, and service providers (NGOs or state-run).

This review has a limitation that, although shared by all systematic reviews, is worth mentioning. The search words and databases chosen allowed access to a sample of Latin American studies but left out others. Also, this review limited its focus to peer-reviewed articles. In Latin America, NGOs and universities carry out research that is not published in academic journals, but is made accessible locally (Guerra & Arredondo, 2017). Although this is a limitation of the review and could be corrected in future systematic reviews, NGOs and universities on the continent should endeavour to publish results in peer-reviewed journals to allow greater visibility and contribution. Attention should be given to cultural considerations and adaptations specific to the Latin American context. There are precedents for this (e.g., Guerra, Toro et al., 2022; Mendes et al., 2022; Parra-Cardona, et al, 2023) and as the scientific community becomes more culturally aware, there exists an opportunity to advance consolidation of psychotherapeutic practice based on culturally sensitive evidence to support IV victims in Latin America.