INTRODUCTION

Stabilizing the occlusion achieved by means of orthodontic therapy is one of the main treatment goals.1)(2)(3)(4) Occlusion instability can be divided into two categories: 1. Changes related to growth, maturation and ageing of dentition and occlusion. 2. Changes produced by the orthodontic treatment. Contact and pressure by soft tissues can be another factor influencing stability.1)(5)(6)(7

The ability to achieve long-term stability and the subsequent understanding of factors affecting stability are an indication for the need to retain the achieved results.1)(2)(4)(5)(7)(8)(9In the absence of a retention phase, teeth tend to return to their initial position. To prevent recurrence, it is necessary to perform some form of retention.6)(7)(10)(11

Many retention devices are currently used to keep the shape of the arch and to prevent recurrence.1)(2)(4)(7)(9)(10)(12)(13)(14) Designed in 1919, the Hawley plate is the most popular removable retainer.15) In 1993, Sheridan et al introduced the Essix plates as a modern, aesthetic, comfortable, and inexpensive alternative to traditional retainers.15)(16) Currently, both the Hawley plate and the Essix® plate are the most widely used removable retainers.15)(16) They have a disadvantage though: they need cooperation by the patient.17)(18

With the introduction of the adhesive technique,19) the lingual retainer has become widely used in recent decades to preserve the changes achieved during orthodontic treatment.9)(12)(20)(21) This consists of a wire of certain length usually bonded from canine to canine on the lingual surface.12)(19

Since its introduction in 1977, several modifications have been made to the wires used.22) The first generation consisted of a rounded wire (0.032-0.036 inches) with terminal folds, bonded to the canines only. The second generation did not require terminal folds, since the wire spiral offered good retention; the disadvantage of this retainer is that its diameter (0.032 inches) produces less stability.9)(22)(23

Rigid multi-stranded wires of a bigger diameter (0.032 inches) have been used in the last ten years (0.032 inches) bonded to the canines only, as well as another type of multi-stranded wire usually more flexible and of a smaller diameter (0.017-0.021 inch), bonded on each tooth from canine to canine.13)(19 The advantage of using multi-stranded wires is that their irregular surface increases mechanical retention with no need of making retentive folds, and the flexibility of the wire allows the physiological movements of teeth.19)(24

As an alternative to this type of wire, glass fiber-reinforced resin tapes are used with the disadvantage that they create a very rigid splint that limits the physiological movement of teeth and can cause fissures.19

Fixed retainers are increasingly used nowadays because they are aesthetic, require less patient cooperation, and provide greater stability in the long term, thus being more predictable.9)(25) However, these retainers make oral hygiene more difficult as the lingual surface becomes more susceptible to the formation of calculus.17)(26)(27) In addition, they may produce gingival recessions, loss of insertion, gingivitis, and the subsequent periodontal destruction.26)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32) Tooth decay may also appear on the lingual surfaces adjacent to the retainer.33

The effect of these retainers on periodontal health is currently debatable.17)(26)(28)(33

The goal of this systematic review is to evaluate the periodontal effects of lingual fixed retainers in the long term.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommended by the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics.

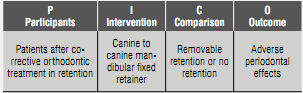

The first stage of this systematic review included the identification of elements to be evaluated, creating a PICO chart (Table 1) and formulating the research question: what are the long-term periodontal effects of mandibular fixed retainers?

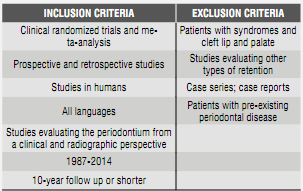

The inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this study are shown in Table 2.

Search methods

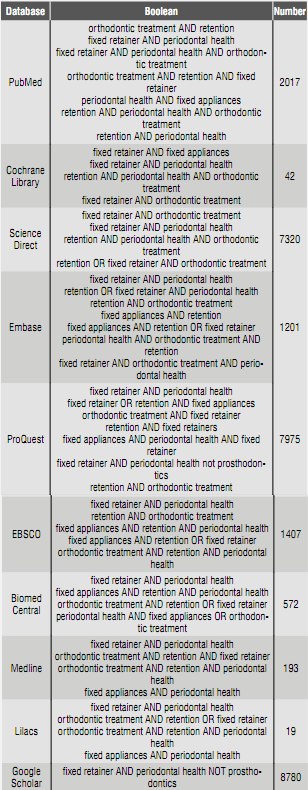

We conducted a search to identify and select studies in the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, Embase, ProQuest, EBSCO, Biomed Central, Medline, Lilacs, Google Scholar, using the following key words: fixed retainer, orthodontic treatment, periodontal health, retention, fixed appliances (Table 3).

Following the first results of the search, we excluded all articles and abstracts that were not related to the topic or did not meet the inclusion criteria. Each search was carried out independently by each researcher; the results were compared reaching to an agreement. If the abstracts did not supply sufficient information, or simply did not exist, full texts were requested to make a final decision.

To locate published material that was not indexed in the available databases, a manual search was conducted in Juan Roa Vásquez library at Universidad El Bosque, reviewing bibliographical references and searching for abstracts or full texts, to find out whether they met the inclusion criteria; this search did not yield any result.

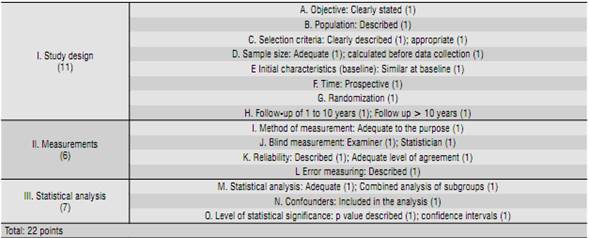

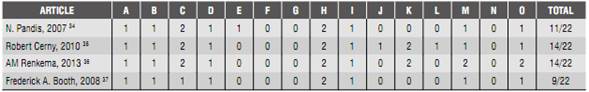

The methodological scoring of the studies is taken from Lagravère and partners,38) with a modification made specifically for this project, which consisted on including studies conducting a follow-up of 0 to 10 years, in order to comply with the inclusion criteria (Table 4). Each selected study received a score (Table 5). The maximum score was 22 points distributed as follows: strong evidence (15-22 points), moderate evidence (8-14 points), and poor evidence (1-7 points). Researchers independently scored each selected article; in case of discrepancies, an agreement was reached by consensus.

RESULTS

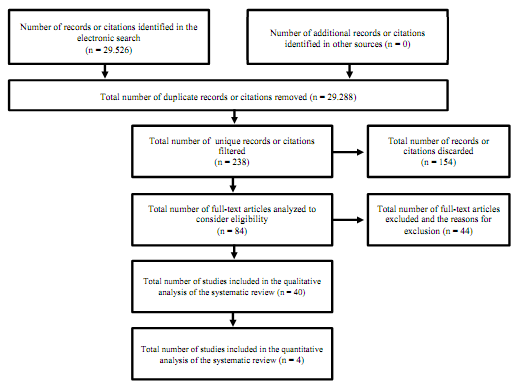

Figure 1 describes the flow chart of information obtained through the different phases of a systematic review (PRISMA). Note that the electronic search in the databases yielded 29.526 titles related to the topic, unlike the manual search, which did not return any related title. Of the 29.526 titles, 29.288 were removed for being duplicates, for a total of 238 unique titles.

The 238 titles were read and 154 were discarded for not being relevant to the topic.

The abstracts of the 84 selected titles were analyzed and 44 articles were discarded for various reasons and by not showing relevance with the subject.

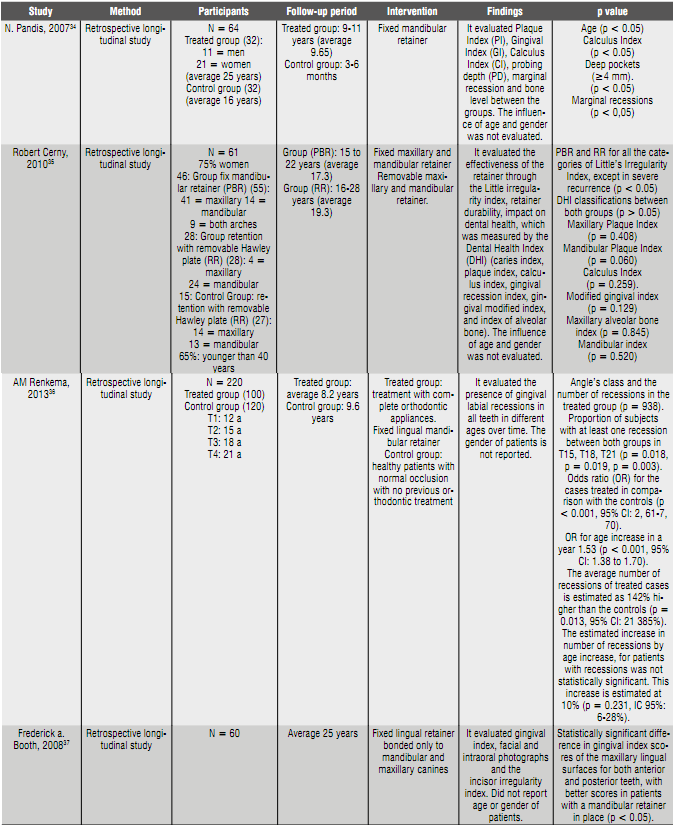

The full texts of the 40 selected articles were analyzed and applied the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Those articles were excluded since they did not evaluate periodontal health but incisor irregularity; in addition, the follow-up period was no longer than two years. In total, only 4 articles met the requirements of this review, and they were evaluated according to the methodology scoring chart. Table 6 shows the characteristics of interest in each selected article.

Calculus Index

A higher calculus index was found by Pandis 34) in the group with long-term retention; on the contrary, Cerny 35) found out that in mandibular lingual surfaces this index scored as very good or good in 80% of the PBR group and 100% of the RR group (p = 0.259). Only a few patients in both groups scored as poor or very poor. The studies by Renkema 36 and Booth (37) did not take this parameter into account.

Gingival index

Of the three studies that evaluated gingival index (Pandis, 34) Cerny, 35 and Booth 37), only one (Booth 37) found statistically significant differences in terms of gingival index scores for maxillary lingual surfaces of both anterior and posterior teeth, with the highest scores in patients with a mandibular retainer in place.

Gingival recessions

The studies by Pandis,34 Cerny,35) and Renkema 36) evaluated the presence of gingival recessions with the use of fixed retainers. The study by Pandis 34) found a high prevalence of gingival recessions in the group using retainers for a long time. A similar result was found in the study by Renkema, 36) which showed a relation between orthodontic treatment and/or the retention phase with gingival recessions over time. They found that the average number of recessions in treated cases is estimated as 142% higher than the control groups, showing an association between fixed retainers and gingival recessions, being the lower incisors teeth more vulnerable. Contrary to these two studies, the study by Cerny 35) found out that none of the classifications of the Dental Health Index significantly differed between the two groups, including gingival recessions, with a tendency to show classifications with lower percentages in the group with fixed retainers, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Bone level

Two of the studies (Pandis 34 and Cerny (35)) found out that, in a follow-up period of 9 to 17 years, bone level with the use of fixed retainers showed no significant differences in comparing short- and long-term removable retainers. In the study by Cerny, 35) the index of maxillary alveolar bone was rated as very good or good in 85% of the PBR group and 90% of the RR group, and in the mandible, it was very good or good in 100% of the PBR group and 90% of the RR group.

Age, gender and Angle’s molar relation

Although the study by Pandis 34) took age into account to observe homogeneity of the groups, only the study by Renkema 36) evaluated gingival recessions at different ages, finding out that age seems to greatly influence the development of gingival recessions since these increased at different measurement times. Regarding gender, none of the studies evaluated its relationship with lingual retainers; only the study by Pandis 34) presented it at baseline. Angle’s classification was considered in the study by Renkema, 36) finding out no differences among classes I, II, and III malocclusions and gingival recessions in the treated group.

Survival of fixed retainers

The survival of fixed retainers was evaluated in two studies (Cerny 35) and Booth 37). In the study by Cerny, 35) 21 of the 242 compound adhesions and 5 of the 55 wire retainers had breaks during 15 years, for a total fractured PBR rate of 3,15% per year and a wire unit/accession fracture rate of 0,58% per year. There were 81% of fractures by adhesion failure and 19% by wire fractures. Of the adhesion fractures, 43% were related to the patient biting something hard, while the causes of the remaining 57% were unknown. Booth 37) found out that 45 patients who still had a retainer in place 20 years later, 28 (62%) had no breaks in that period, 18% required one repair, and 20% required more than one repair.

DISCUSSION

The present systematic review focused on determining the periodontal effects of fixed retainers in the long term during the retention phase following orthodontic treatment. All the articles finally selected were of a retrospective type and showed moderate evidence.

None of the studies was randomized or calculated sample size. Only one of the four articles presented similar characteristics at baseline. Only one study 35) reported blind examiner; none of the others included blinding in measurements or statistics. Two of the studies 34)(37) failed to report reliability of measurements. Only one of the studies reported error.35) On the other hand, the statistical analysis was appropriate in all the studies; however, only one 36) reported having carried out combined analysis of subgroups. Confounders were not considered in any of the studies and the p value was described by all, but only one 36) established confidence intervals.

Previous studies have evaluated the periodontal effects of retainers in different time periods. Levin et al evaluated the association of orthodontic treatment and fixed retainers with gingival health. Periodontal parameters, plaque index, gingival index, gingival recession, and depth and bleeding on probing were measured on six sites per tooth. They concluded that fixed retainers are associated with the increase in gingival recessions, plaque retention and bleeding on probing. Therefore, they recommended meticulous oral hygiene and regular visits to the dentist for monitoring.29

On the other hand, Artun et al analyzed the tendency to the formation of plaque and dental calculus on the wire of different types of fixed orthodontic retainers from canine to canine and one removable retainer. The 49 patients included in the study were sorted out into 4 groups; there were 11 patients in the group of plain fixed retainers cemented in canines only, 13 patients in the group of fixed retainers made of multi-stranded wire cemented in canines only, 11 patients in the group of retainers made of multi-stranded wire but cemented in all teeth from canine to canine, and 14 patients in the group of removable retainers. Each group was evaluated 3 years after having placed the retainers, to determine the accumulation of plaque and calculus and gingival inflammation along the gingival margin of incisors and mandibular canines, based on Löe’s plaque index and gingival index, as well as Ramfjord’s calculus index. The authors concluded that the presence of a fixed retainer doesn’t seem to have any negative periodontal effect, if patients perform satisfactory hygiene along the gingival margin.21

In a prospective study, Al-Nimri et al evaluated gingival health and the accumulation of plaque in lingual retainers made of multi-stranded wire cemented to all anterior mandibular teeth, comparing them with retainers made in round wire and cemented in canines only. The evaluated parameters were: index of oral hygiene, plaque index, and gingival index in lower anterior teeth. They concluded that there were no significant differences in the gingival condition of lower anterior teeth with the fixed multi-stranded wire nor with the fixed retainer made of round wire.30) The aforementioned studies were not included in this research project because they did not meet the follow-up time criterion (0 to 10 years).

This systematic review included four studies evaluating the periodontal effects of fixed retainers in a period of ten years or less, with different measurement variables.

The results obtained in terms of calculus index are not conclusive because this parameter was evaluated in two of the studies which differ between them, since Pandis et al 34) claim that there was a greater calculus accumulation in patients with fixed lingual retainers evaluated in a long period, while Cerny et al 35) found satisfactory results in 80% of the evaluated cases with fixed retainer and in 100% of cases with removable retainers. The same happens with gingival index, which was evaluated in three of the four studies, but only Booth et al 37) found statistically significant differences in the maxillary lingual surfaces, while Pandis 34) and Cerny 35) found no differences.

In terms of gingival recessions, Pandis 34) and Renkema 36) found association between the presence of a lingual fixed retainer and the development of gingival recessions; however, Cerny 35) found no significant difference between the studied groups. On the other hand, Renkema 37 found a relation between patient's age and the appearance of gingival recessions.

The results of the two studies 34)(35) that evaluated bone level changes are in agreement, stating that there are no significant differences between the groups observed in the short and long term, nor among the groups using fixed retainer and removable retainer.

Two studies evaluated the incisive irregularity index, finding out slight changes in this sense. Observing patients with 15 years of retention, Cerny found an index of irregularity of 0.26 mm in patients with retainers fixed. Booth’s results agree with Cerny’s, finding out that only 1 of 45 patients showed an index of irregularity greater than 2 mm.35)(37) No article reports differences in maxillary and mandibular retainers.

Since the information found is limited, and given that most results are not conclusive, no absolute conclusions can be drawn; it is therefore recommended to conduct more research and randomized clinical trials, in order to determine the periodontal effects of lingual fixed retainers in the long term. However, is important to highlight that most authors refer to the importance of encouraging patients to keep good oral hygiene to avoid later periodontal complications.

CONCLUSIONS

1. There is association between gingival recessions and fixed retainers in the long term; however, there is no alteration of the alveolar bone level.

2. The results should be cautiously taken due to the middle level of evidence found.

3. The recommendation for clinicians is that these retainers seem to be safe in the long term, provided that patients are instructed in good oral health habits in order to reduce the accumulation of plaque and calculus.

text in

text in