Introduction

In 1987, the Bruntdland Commission released the report “Our common future,” which defined sustainability as the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). With a continuously growing population, producing more food with the Earth’s finite resources while reducing the environmental impacts requires sustainable intensification, changing agronomic practices, and adopting activities such as integrated pest management and agroforestry (Charles et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, agricultural activities have specific characteristics that harm and benefit environmental quality. Traditional farming can deteriorate the soil, water, and air quality, causing a loss of habitats and biodiversity. Still, it has positive impacts, such as acting as a sink for greenhouse gases, conserving and enhancing biodiversity, and preventing flooding and landslides. Agricultural systems must be improved to face the challenges of increasing food production to solve hunger problems and maintaining food production while increasing environmental goods and services (Pretty, 2016).

Just like the word sustainability, the concept of sustainable agriculture is ambiguous. The US Congress defined it in 1990 as an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application that will, over the long term: (a) satisfy human food and fiber needs; (b) enhance environmental quality; (c) make efficient use of non-renewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate appropriate natural biological cycles and controls; (d) sustain the economic viability of farm operations; and € enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole. (Public Law 101-624, 1990).

Sustainability in agriculture is a dynamic concept that includes environmental, social, economic, and resource use that can vary with time, location, society, and priorities. Its primary intention is to minimize external inputs and maximize outputs while maintaining the resources and achieving socioeconomic, environmental, and economic welfare (Mishra et al., 2018). Sustainable agriculture requires integrating practices framed within sustainability that are productive, competitive, and efficient while protecting and improving local communities’ environment, ecosystem, and socioeconomic conditions (Mishra et al., 2018).

The Driving Force-State-Response framework “considers the specific characteristics of agriculture and its relation to the environment,” addressing a set of questions such as: “What is causing environmental conditions in agriculture to change (driving force)? What actions are being taken to respond to changes in the environment in agriculture (response)?” (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 1999). The analysis derived from addressing these questions can help to understand the response and feedback by farmers, policymakers, and society. Driving forces cause environmental changes and cover the influences in sustainable agriculture, such as farmer behavior, policies, and other factors (Jambo et al., 2019). The University of Alberta states, “Adopting sustainable practices, whether large or small, can have significant impacts in the long run” (University of Alberta, 2013). This statement supports the aim of this study, which is to conduct an in-depth literature review to identify the drivers in the agriculture sector and boost the effective deployment of methodologies, mechanisms, and strategies focused on the transition to sustainable development in the industry.

Section 1 of the article is the theoretical framework, followed by Section 2, the methodology, which is divided into four stages. Section 3 shows the results from the literature review, which were analyzed qualitatively using the software Vantage Point 10.0; Section 4 presents the discussion regarding the results, and Section 5 concludes.

This article can represent an essential input for academics willing to implement initiatives that seek to understand, take advantage of, and potentiate the internal and external drivers that facilitate adopting agriculture practices or projects framed within sustainability and the success of practical implementations.

Materials and Methods

Generally, a literature review can be defined as selecting available information on a specific topic and effectively evaluating this documentation for proposed research (Hart, 1998). The most common classification of literature reviews divides them into narrative literature reviews, systematic literature reviews, and meta-analyses (Cronin et al., 2008).

In this context, we have chosen a qualitative approach similar to that proposed and applied in literature review methodologies published in different agroindustry studies: Ciprian et al. (2022), Hernandez et al. (2021), Solarte et al. (2021), and Zartha et al. (2021b,c). Innovation and technology management studies include Zartha et al., 2021a, while sustainability was addressed by Álvarez et al. (2019) and Betancourt and Zartha (2020).

The first stage of the literature review was the selection of Scopus as the primary source of information and the keywords that would help achieve the objective of the study, which were “driver,” “adoption,” or “uptake,” “sustainab*,” and “agriculture.” Next, the search equation was constructed: TITLE-ABS-KEY (driver AND (adoption OR uptake) AND sustainab* AND agriculture), resulting in 118 articles. The abstracts of all articles were reviewed, so 47 papers were selected for the literature review regarding situations where there was a transition toward sustainable agriculture practices. The drivers that allowed and facilitated their adoption were further analyzed.

An Excel table was created with the following fields to facilitate the analysis: name of the article, abstract, keywords, if the paper has a literature review as part of its methodology, authors, year, country of the authors, place of study, source, Scimago Journal Rank, Scimago Quartile, agriculture sector, methods used to find drivers, drivers, sustainable agriculture activity adopted, and classification depending on whether the driver is external or internal to the farmer.

Once the 47 selected articles had been read, Vantage Point 10.0 was used as a source of analysis, with a table with the following categories as input: abstract, keywords, year of publication, journal, country of the authors, place of study, Scimago Journal Rank, and Scimago Quartile. Figure 1 shows all the stages of the methodology.

Results

This section shows the results from the analysis of the 47 selected articles, where the relationship with the objective of this article is explicitly understood from their title, abstract, and keywords. The figures and tables below were constructed considering relevant information from each article, such as keywords, place of study, year of publication, source of information, Journal’s SJR, and Scimago quartile.

As mentioned above, the systematic literature review was followed as the methodology for this article to determine how many articles had this same methodology for their construction. As shown in Figure 2, 38% of the analyzed articles followed a literature review as part of their methodology, and the remaining 62% did not.

Since the year of publication was not taken into consideration in the structuring of the search equation, the 47 articles selected were grouped into periods (Figure 3) as follows: between 2004 and 2008, five articles; between 2009 and 2012, seven articles; between 2013 and 2016, 12 articles, and finally, between 2017 and 2020, 23 articles.

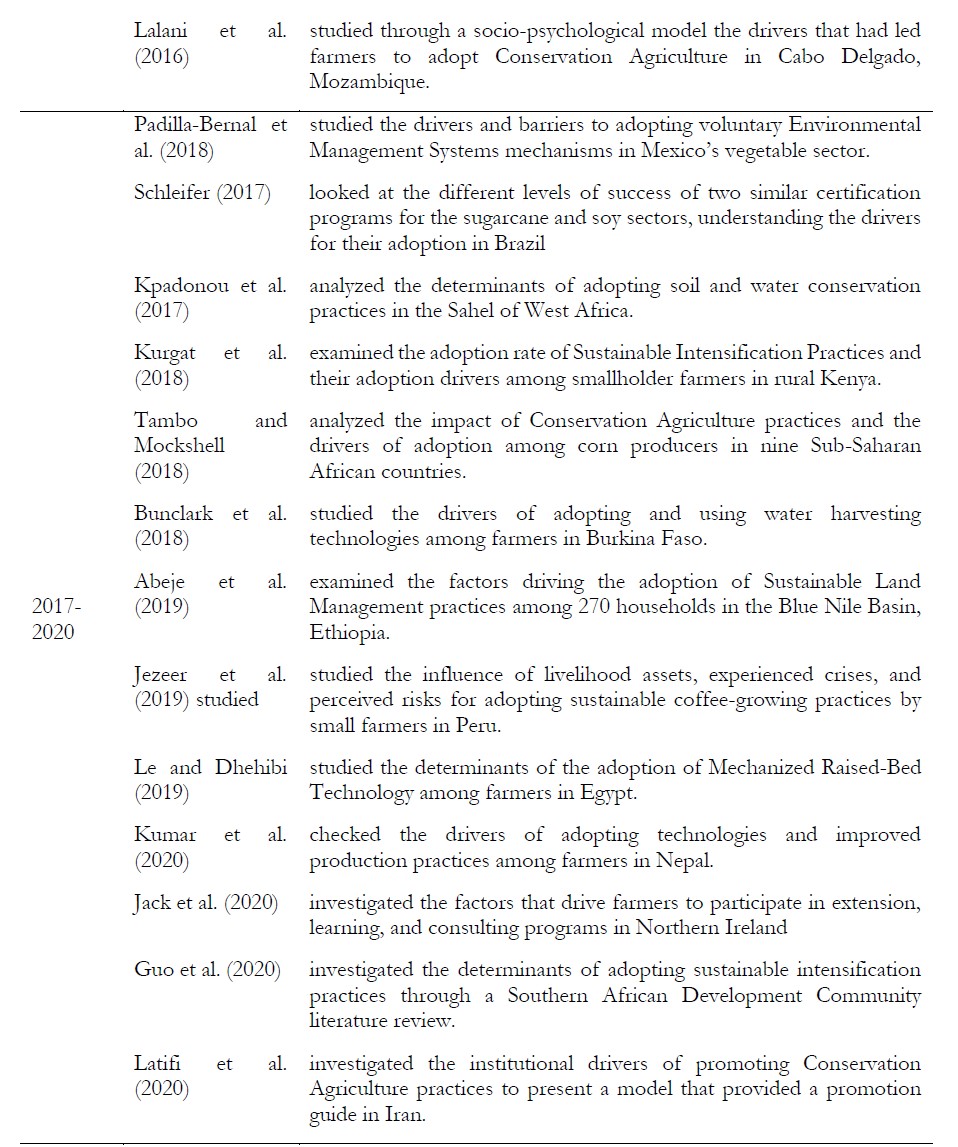

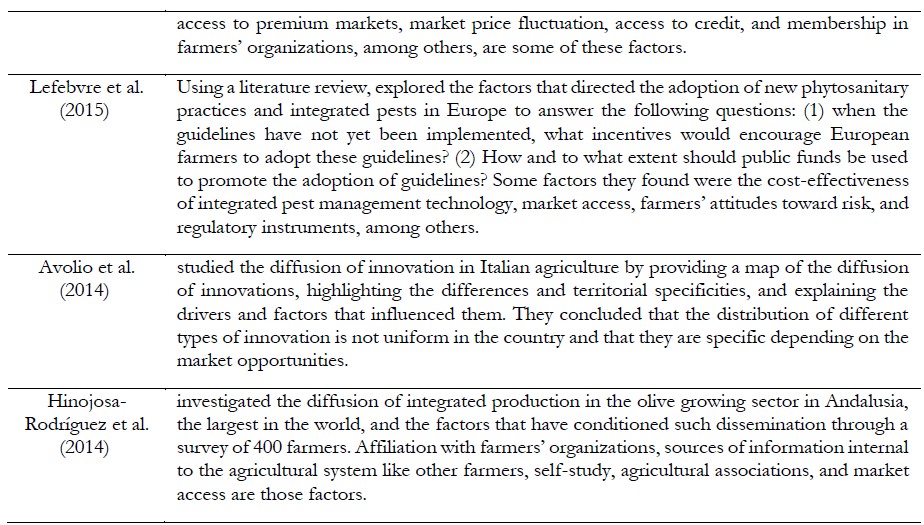

The Table 1 is presented below, which lists the studies in the period between 2004 and 2020.

As shown in Figure 4, the subject matter of 58% of the articles was located in countries from Africa, mainly Tanzania and Malawi, followed by Europe with 12% of the articles reviewed and Asia and North America with 8% each.

One of the most common keywords among the articles reviewed was “Adoption,” which was used in eight articles (17%), followed by “Conservation Agriculture” and “Sustainable Agriculture,” which were used in five articles, respectively. “Drivers” was a keyword in two articles reviewed. However, it was common to find this word accompanying others such as “External drivers,” “Socioeconomic drivers,” “Social drivers,” “Economic drivers,” “Social/political drivers, “Environmental drivers, “and” Technological drivers, “for a total of seven articles (14%).

Drivers for the adoption of sustainable agriculture activities

The objective of this study was to analyze the different drivers or change-makers that allow the adoption of sustainable practices in the agricultural sector in different situations. Each driver was classified as “internal” or “external.” It was considered internal if the driver was within the limits of the production system and, therefore, under the farmer’s control or external if the driver was not under the farmer’s control. For each situation, we analyzed which sustainable agriculture activity was intended to be adopted, the agricultural sector of the case study, and the country where the study was carried out.

Table 2 is presented below, where some internal variables analyzed are observed.

During the review, 14 articles reported drivers considered external, as shown in Table 3. Most authors found both types of drivers in their papers, internal and external (Table 3).

Appendix 1 shows the compilation of the 259 drivers found in the literature review, which has different categories such as their classification of external or internal, country of study, sector, and the sustainable activity to be adopted.

An additional analysis was carried out in Vantage Point with the top 11 Drives and top 11 keywords through a co-occurrence matrix ending in a Bubble chart. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 5, highlighting the contributions of 11 drivers to adoption, ten to livelihood, eight to sustainability, eight to conservation, six to sustainability agriculture, five to technology adoption and sustainable intensification, two to water conservation, and one to agriculture and natural recovery. Regarding the keywords, three thematic groups can be noted: sustainability, which encompasses the keywords sustainability, sustainability agriculture, sustainable development, and sustainable intensification; technology adoption, which includes adoption; and natural resources, which encompasses variables such as conservation.

Conclusion

During the literature review of the 47 papers, we identified 259 drivers for adopting sustainable agriculture activities. The driver occurring the most was “Education,” which was present in 13 papers, followed by “Affiliation with farmers’ organizations” in seven articles. Of note is that the drivers “Household income,” “Land tenure,” and “Market access” appeared in six articles, respectively. In 27 articles, the agriculture sector was not specified, so we decided to set it as “General agriculture.” Horticulture and maize production are sectors that appeared three times respectively in the review. Conservation agriculture was the sustainable agriculture activity whose adoption was studied the most. Other activities were Environmental Management Systems, Integrated Pest Management, and Sustainable Intensification Practices, which were analyzed in three articles, respectively. As part of the literature review, the authors analyzed external and internal drivers; in most cases, both types were studied. In 24 articles, the authors studied both types, representing 51 %. Fifteen articles (32 % of the papers) presented only external drivers, and the remaining 17 % were only internal.

The countries of study of 58 % of the articles are in Africa, mostly Malawi, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, and Mozambique. Regarding the Americas, the United States was the country where most of the studies were conducted, followed by Mexico and Brazil.

During the literature review, it was necessary to include the keywords “adopt” and “uptake” to direct better the search equation because the word “driver,” used alone, was related to agriculture as a driver of negative impacts, such as deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, soil erosion, among others. This may represent an opportunity for a new literature review where other words that replace the word “driver” are investigated to get a complete vision of the drivers of sustainable agriculture and not only the adoption process of activities framed within sustainable agriculture. Since “innovation” appeared in two articles, we recommend including this keyword because the transition to sustainable agriculture could mean innovation in many practices being carried out on the farm and considered new to the farmers.

This article can represent an essential input for academics willing to implement initiatives that seek to understand, take advantage of, and potentiate the internal and external drivers that facilitate adopting agriculture practices or projects framed within sustainability and the success of practical implementations. The compilation and classification of the drivers constructed in this literature review could be helpful for companies that work with farmers and need to structure a strategy for adopting sustainable agriculture activities. Also, understanding the external drivers presented here by people working in the public sector can help design sustainable public policies for the primary sector so the farmers’ perspectives are considered.

Authors’ contributions

Mariana Herrera Arango and Laura Restrepo Campuzano read the papers and classified the drivers. Gina Lia Orozco Mendoza constructed the search equation and used the Vantage Point software. Gustavo Adolfo Hincapie Llanos and Jhon Wilder Zartha Sossa reviewed the paper in general and contributed to the respective analysis of results and conclusions.