Migration is the movement of people from one state to another by way of which people not born in a territory arrive to settle there (International Organisation for Migration, 2006). Over the last few decades, there has been a steady increase in the number of migrants worldwide, and this number is expected to reach 400 million by 2050, twice that of 2015 (United Nations, 2010).

The process of migration involves several challenges, demands, and stressors, many of which are linked to the uncertainty of economic and social stabilisation in the new context, affecting the health and well-being of migrants (Urzúa et al., 2019b). Migration has a major impact on mental health, and there are multiple reports on the prevalence of depression (DEP) or anxiety (ANX) disorders in the migrant population (Breslau et al., 2011; Familiar et al., 2011; Urzúa et al., 2016; 2017; 2019a; 2020a), which have been linked to negative health-related outcomes, such as cardiovascular diseases (Shen et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2015), excess weight (Kamody et al., 2018), increased risk of developing diabetes (Smith et al., 2018), and eating disorders (Hun & Urzúa, 2019).

There are reports of a bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms and excess malnutrition (Luppino et al., 2010; Rooke & Thorsteinsson, 2008). This dynamic is alarming considering that more than 1.9 billion people over the age of 18 are overweight, of which more than 650 million are obese (World Health Organization, 2017a). Additionally, more than 264 million people of all ages suffer from depression, which is a major contributor to the global burden of eating disorders (WHO, 2018).

In this context, the eating behaviour of the migrant population plays a dominant role because it functions as an axis of articulation between physical and mental health. Unfortunately, the evidence is not encouraging since migration has reported significant associations with excess malnutrition (Jäger et al., 2022), development of chronic non-communicable diseases, and poor mental health indicators (Buscemi et al., 2009; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2003; Holmboe-Ottesen & Wandel, 2012; Martin et al., 2017; Wiley et al., 2013). This situation is negatively enhanced when considering that anxiety and depression can lead to an increase in the consumption of hypercaloric foods rich in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates (Firth et al., 2020; Holmboe-Ottesen & Wandel, 2012) and, consequently, can increase the risk of overweight and obesity (Ferrer-García et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2012).

The relationship between migration and overnutrition can partly be explained by emotional eating (EE). Emotional eating is considered an obesogenic eating style, since it refers to the tendency to eat as a response to negative emotions, such as depression, anxiety, and stress (Konttinen et al., 2019; Palomino-Pérez, 2020), and in which the preferred foods are characterised mainly by their high energy density and palatability (Oliver et al., 2000; Van Strien et al., 2012). Migrants living in Chile have reported higher consumption of hypercaloric foods than Chileans and a lower tendency to consume foods according to their positive nutritional characteristics (Hun et al., 2020a).

Affectivity is fundamental in the context of emotional eating. The literature identifies positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) as different dimensions of emotional experience (Quinceno & Vinaccia, 2014; Watson & Tellegen, 1985; Watson et al., 2011). PA is related to well-being and satisfaction with life, while NA relates to anguish and difficulty in overcoming complex situations (Chavarría & Barra, 2014; Ortíz et al., 2016; Pedrosa et al., 2015; Urzúa et al., 2020b; Vera-Villarroel et al., 2016). The greater part of the reported evidence links NA to a greater presence of anxiety and depression symptoms, given their relationship with distress, highly stressful situations, and problems regarding how to overcome these situations (Urzúa et al., 2020a). In contrast, PA has been reported to have a suppressive effect on NA. In this sense, a greater presence of PA would suppress NA, which could contribute to the reduction of anxiety and depression symptoms and, consequently, a decrease in emotional eating (Hun et al., 2020b).

The present study focuses on the Colombian migrant population in Chile, which has grown exponentially in the last 25 years, increasing from 0.8% to 4.4% of the total population in 2017 (INE, 2021). Nearly half of the migrants (50.4%) are originally from three Latin American countries: Peru (25.2%), Colombia (14.1%), and Venezuela (11.1%). In recent years, our research group has focused on the Colombian migrant population, given that, unlike the others, these migratory waves have generated frequent episodes of ethnic and racial discrimination (Gissi-Barbieri & Ghio-Suárez, 2017; Sanz, 2014). Our research has reported evidence regarding the presence of mental health problems among the migrant population in Chile (Urzúa et al., 2017; 2019b; 2020a) and the consequences this may have on eating behaviours, exploring the role of mediating variables (Hun et al., 2020b). However, although there is evidence regarding the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between mental health (Hernández-Alvarado et al., 2021) and emotional eating in the migrant population, this evidence is deficient. Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyse the mediating repercussions of PA and NA on the relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms and emotional eating. The hypotheses are as follows: (1) PA diminishes the tendency towards emotional eating, and (2) NA facilitates the tendency towards emotional eating associated with anxiety and depression symptoms. Given the influence of gender on the relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms and emotional eating (Hun et al., 2020b), we have controlled the analyses by sex. In addition, we have also controlled by economic activity, given the possible incidence this has in the relationship to be studied.

Method

Participants

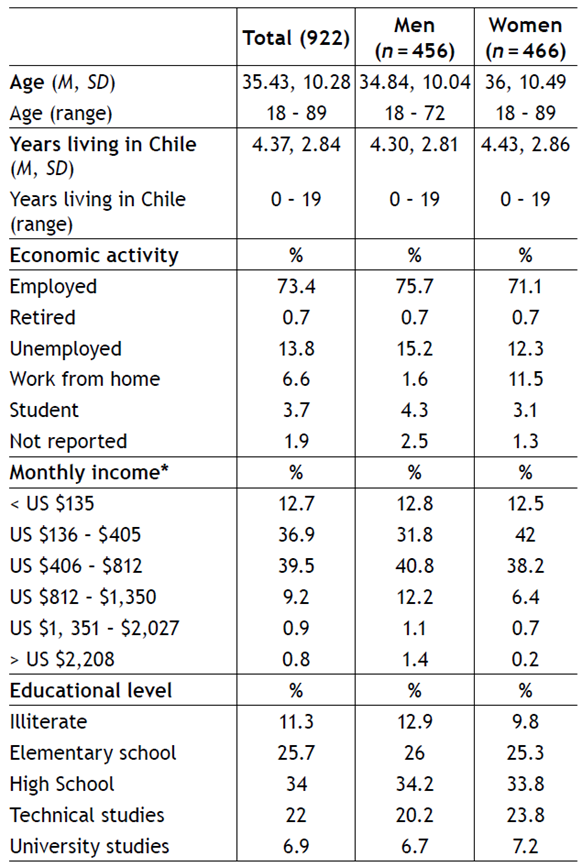

The sample comprised 922 first-generation Colombian migrants in Chile, of whom 466 were women (50.5%) and 456 were men (49.5%). The age range was 18-89 years, and the average age was 35.43 years. Participants were recruited from three cities in Chile, two in the northern zone (Arica and Antofagasta) and one in the central zone (Metropolitan Region). It should be noted that the Metropolitan Region and the Antofagasta region are the two regions with the highest number of visas issued between 2005 and 2018 (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2021).

Instruments

Anxiety. We adapted the Sanz (2014) Spanish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI;Beck et al., 1988) composed of 21 items to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms. The participants self-reported the degree to which they were affected by anxiety symptoms during one week. The responses were rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (severely). The Cronbach’s alpha was .945 for the present study.

Emotional eating. Emotional eating was measured using a subscale of the Spanish version of the Dutch Eating Behaviour (DEBQ; Van Strien et al., 1986) adapted for adult Chileans by Andrés et al. (2017). The emotional eating subscale contains 13 items measuring the influence of emotions on food selection and consumption, with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The Cronbach’s alpha was .861 for the present study.

Positive and negative affect. To measure affect, we used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) questionnaire developed by Watson et al. (1988), which contains subscales to measure PA and NA. The participants read 20 words describing different feelings and emotions (for example, guilty or inspired), and indicated the degree to which they respond to these emotions. The responses are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (nothing or almost nothing) to 5 (a lot). The Spanish version of the questionnaire was used in the present study, which has already been employed in previous studies in Chile (Vera-Villarroel et al., 2019). Cronbach’s alpha for PA was 0.875 and for NA was 0.876.

Depression. Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996), which consists of 21 items designed to assess the severity of depression symptoms. Response to each item ranges from 0 to 3, from less to more severe, with the total score varying from 0 to 63. In the present study, the Spanish version of the BDI-II was used (Sanz et al., 2003), which yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .929.

Procedures

This study is part of a larger project to evaluate the health and well-being of the Colombian migrant population in Chile, which was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad Católica del Norte by way of resolution 011/2018. The participants were selected using the snowball technique combined with intentional sampling (Johnson, 2014). Before participating, the participants filled out an informed consent form. Subsequently, a series of questionnaires were administered to the participants.

Data analysis. Figure 1 shows the analysed theoretical model. The mediation models were analysed using Mplus 8.2 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), through the robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation method, which is robust for non-normal ordinal variables (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006). The goodness-of-fit of the models was estimated using chi-square values (x2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker Lewis index (TLI). According to recommended literature standards (Stride et al., 2015), RMSEA ≤ .08, CFI ≥ .95, and TLI ≥ .95 indicate a good fit. Due to the extension of the model, a process of parcelling was carried out, following which the BAI, BDI-II, PA and NA subscales, and emotional eating subscale were reduced to seven, eight, ten (five items per subscale), and six items, respectively. To examine the mediating effect of PA and NA on the relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms and emotional eating, the recommendations of Stride et al. (2015) were followed.

Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. No statistically significant differences were found between men and woman with respect to duration of residence, type of economic activity, monthly income, and education level of the participants.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

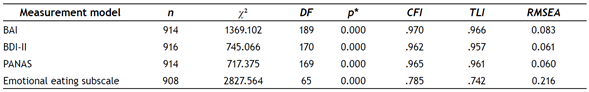

Table 2 lists the measurement models for the instruments used. The BDI-II and PANAS presented adequate adjustments, whereas the BAI and emotional eating subscale presented moderate adjustments (54).

Table 2 Indicators of global adjustment of the measurement models in the total sample

Note. BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, PANAS = Positive affect and negative affect schedule, DF = Degree of Freedom, CFI = Comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker Lewis Index, RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation, * p < .001

Anxiety and depression symptoms and emotional eating

Figure 2 shows the standardised structural model of the mediating effect of PA and NA on the relationship between mental health symptoms (ANX = anxiety; and DEP = depression) and emotional eating (EE). The model presented an adequate fit (x² = 5631.225, DF = 2764, p = .000, CFI = .952, TLI = .950, RMSEA = .034).

Figure 2 Mediating effect of positive and negative affect on the relationship between anxiety and depression as independent variables and emotional eating as dependent variable.

ANX and DEP presented a positive and statistically significant correlation (r = .457, p = .000). ANX presented positive and statistically significant effects on NA (direct effect = .330, p = .000) and EE (direct effect = .346, p = .000). ANX had a negative and statistically significant effect on PA (direct effect = −.218, p = .000). DEP presented positive and statistically significant effects on NA (direct effect = .195, p = .000) and EE (direct effect = .090, p = .020). DEP had a negative and statistically significant effect on PA (direct eff-ect = −.208, p = .000). PA had no statistically significant effect on ES (direct effect = −.032, p = .368). NA presented positive and statistically significant effects on EE (direct effect = .076, p = .042).

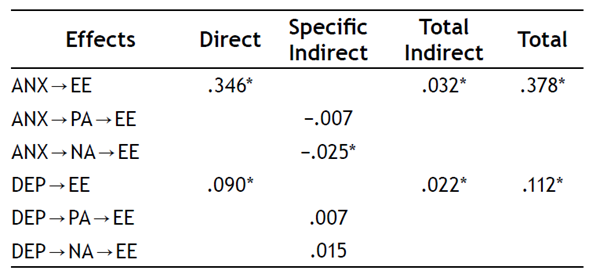

The indirect effects can be seen on Table 3. Only NA presented a specific and statistically significant indirect effect between ANX and EE (specific indirect = −.025, p = .044). PA and NA together presented a total and statisticallysignificant indirect effect between ANX and EE (total indirect = .032, p = .029). PA and NA together presented a total and statistically significant indirect effect between DEP and EE (total indirect = .022, p = .048).

Discussion

The objective of this study is to analyse the mediating effect of PA and NA on the relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms and emotional eating. The hypotheses are as follows: (1) PA diminishes the tendency towards emotional eating, and (2) NA facilitates the tendency towards emotional eating associated with anxiety and depression symptoms. We have controlled analyses by sex and economic activity.

Previous research considered that feelings of interest, enthusiasm, and pride diminish the tendency towards emotional eating (Wang & Zhou, 2022). The results indicate that PA does not significantly mediate the relationship between anxiety and emotional eating. Therefore, the possible protective role of PA could not be evidenced in this group. On the other hand, NA positively and significantly mediated the relationship between anxiety and emotional eating. In this sense, feelings of guilt, fear, or shame enhanced the relationship between anxiety and emotional eating. This relationship could be explored as a possible risk factor since emotional eating is closely linked to obesogenic eating (Hun et al., 2020b; Konttinen et al., 2019; Palomino-Pérez, 2020; Van Strien et al., 1986).

Regarding the relationship between depression symptoms and emotional eating, the dynamics were similar to those of anxiety symptoms. PA did not significantly mediate the relationship, without the protective potential for nutritional health previously described in the relationship between anxious symptomatology and emotional eating, which is linked to indicators of psychological well-being described in the literature (Benzerouk et al., 2021; Vera Villaroel & Celis-Atenas, 2014). Similarly for NA, a significant and positive mediating effect was observed. In this sense, the fact that NA favours the relationship between depressive symptomatology and eating can be considered as a risk factor for excess malnutrition as in the relationship with anxious symptomatology (Hun et al., 2020; Konttinen et al., 2019).

These results are disconcerting because previous research has reported a protective consequence of PAs respecting decreased emotional eating (Wang & Zhou, 2022) and better indicators of well-being (Pierce et al., 2018). However, the results in the Colombian population residing in Chile did not report said protective consequence of PA. On the contrary, it was NA that presented a mediating effect of both anxious and depressive symptomatology on emotional eating. In this regard, a decrease in NA would be a protective factor, but an increase in PA would not.

Emotional eating can manifest itself in both international and internal immigrants. In the case of international immigrants, emotional eating may be related to the process of adapting to a new culture, social isolation, and discrimination. These factors can generate stress and anxiety, leading to the use of food as a form of comfort or gratification. In the case of internal migrants, who move within their own country, emotional eating may be influenced by the breakdown of family structure or the loss of community ties. Although both groups may resort to emotional eating, the specific experiences of each type of migrant may result in different triggers and contexts that influence their eating patterns and how they cope with negative emotions through food.

This study is important in that it contributes to evidence regarding eating styles and mental health in a migrant population, which is a line of research that has been scarcely explored in general terms and practically non-existent in Latin America (Hun & Urzúa, 2019). The future developments in this research area can potentially provide recommendations for the development of public policies that favour the well-being of the migrant population (Castro-Sánchez & Mojica-Pérez, 2020; WHO, 2019).

Regarding the limitations of this study, it is essential to continue exploring these relationships and to consider longitudinal studies that allow for the analysis of the evolution of various associated variables. Finally, it is important to emphasise the need to replicate these models in migrants of different nationalities and host territories1 2 3.