Introduction

The Sacred Scripture articulates in a theological manner diverse phenomenological manifestations of conviction and security encountered through an experiential relationship with God.1 It is necessary, therefore, to elucidate and clarify the basic meaning of the Old Testament vocabulary that has been used by the original authors in order to express their personal relationship with YHWH in concrete historical contexts. These “facts of language are interpreted from the perspective of a usage-based model, according to which language is built from actual usage events”.2

Such historical contexts with its respective linguistics usage imply, other than the moment of the revelation itself, a way of expression of the revealed truth through the faith of Israel as it evolved from the moment of its concrete experience until it had been conveyed within fixed theological and linguistic notions.

Following this methodological reasoning, the semantic analysis of the vocabulary of faith employed by the hagiographers must be the essential platform on which to discover its theological value. The semantic examination uncovers the original semantic nucleus of the verb  in its proper context while determining its most original message according to the real intention of the author manifested in the qal forms. It is important to clarify that a lexeme manifested in different binyamin, as it is the case of nifal and hifil, can adopt different semantic levels that are not necessarily related or derived from the qal. However, in the case of the root

in its proper context while determining its most original message according to the real intention of the author manifested in the qal forms. It is important to clarify that a lexeme manifested in different binyamin, as it is the case of nifal and hifil, can adopt different semantic levels that are not necessarily related or derived from the qal. However, in the case of the root  there has been a philological debate in order to elucidate its original meaning.

there has been a philological debate in order to elucidate its original meaning.

Alfred Jepsen encounters this issue exposing the possible archaic meanings of the root, using comparative analysis with different languages such as Arabic, Aramaic, and Syriac.3 He indicates that the lexeme has a strong connection with the Arabic ’amina that can conjointly signify “secure” and “faithful”. The same term implied the equivalent in the meaning of qal and nifal, not excluding each other, since one meaning includes the other.4 Therefore, Jepsen in his philological analysis supports the semantic value of qal as one of the essential manifestations in the meaning of the root in order to clarify its fundamental meanings.5

Therefore, the current essay presents a semantic analysis of the verb of  under the approach of Sachexegese6, in order to highlight its theological meanings and interpretation that express an essential aspect of the semantic analysis. Using this methodological approach emphasizes the effort to interpret the verb

under the approach of Sachexegese6, in order to highlight its theological meanings and interpretation that express an essential aspect of the semantic analysis. Using this methodological approach emphasizes the effort to interpret the verb  in light of the central concern of the biblical texts, which are theological in nature.7 Consequently, the present semantic methodology offers a synchronic and diachronic Semasiology of the aforementioned verb that goes beyond the simplistic lexicographic analysis of the studied term.8

in light of the central concern of the biblical texts, which are theological in nature.7 Consequently, the present semantic methodology offers a synchronic and diachronic Semasiology of the aforementioned verb that goes beyond the simplistic lexicographic analysis of the studied term.8

As one of the branches of semantics, Semasiology studies a specific word or lexeme starting from its form, then analyzes and decodes the diverse meanings associated with it throughout the different texts and historical contexts in which a term may appear. Semasiology also studies the semantic changes of a term, as it is in the particular case of the shoresh  in order to determine its semantic changes. If we cannot first establish which is its most fundamental meaning, then it would be difficult to use it as a point of reference to determine alternative added meanings applied throughout specific historical contexts.

in order to determine its semantic changes. If we cannot first establish which is its most fundamental meaning, then it would be difficult to use it as a point of reference to determine alternative added meanings applied throughout specific historical contexts.

While this essay does not pretend to offer a solution to this philological problem, its purpose is to reconsider the semantic value of qal as a substratum or source domain for the interpretation of the different binyanim. The synchronic approach presented in this essay does not exclude the diachronic dimension of the theological notions of the Old Testament. Such notions can imply a transformation of meaning that goes from a concrete and objective meaning of “protection, care, and security” to a more abstract and theological meaning that implies “faith, trust, or faithfulness”.9 However, using the semantic analysis of significant pericopes, it is possible to identify the most important theological meanings of the primeval semantic substratum of its qal conjugation that permeates the different morphosyntactic variations of the root  .10

.10

The verb אָמַן as lexis of faith

In the books of the Old Testament11, the most important vocabulary12 to express the notion of faith derives from the Hebrew root  . This philological root cannot be found attested in Akkadian, Ugaritic, and Phoenician, but it has a great variety of semantic nuances in the biblical Hebrew13, depending upon the conjugation and literary context in which the root is employed in the biblical narrative. According to this line of argumentation, I would like to highlight the assertion of Moberly, who affirms:

. This philological root cannot be found attested in Akkadian, Ugaritic, and Phoenician, but it has a great variety of semantic nuances in the biblical Hebrew13, depending upon the conjugation and literary context in which the root is employed in the biblical narrative. According to this line of argumentation, I would like to highlight the assertion of Moberly, who affirms:

There are five forms of the ʼmn root that are of theological significance: the two related nouns ʼemet and ʼemûnâ, the adverb, ʼāmēn, and the two forms of the verb neʼemān (ni.) and heʼemîn (hi.). Other forms either have no special theological significance or have a significance that is similar to, and probably a derivative from the five forms described here.14

Moberly’s opinion represents the predominant academic line of thought that is also attested to in the considerable work of Wildberger.15 For the majority of biblical exegetes, as are the two aforementioned important authors, the most significant verbal forms of the root  are neʼemān (nifal) and heʼemîn (hifil) as the fundamental forms of the root

are neʼemān (nifal) and heʼemîn (hifil) as the fundamental forms of the root  in the Old Testament.

in the Old Testament.

Without denying the significant biblical contributions in the elucidations of the shoresh in nifal and hifil, I was compelled to focus my attention on the semantic and theological importance of the qal conjugation. The majority of the exegetes consider the qal conjugation of  as having no significance under the theological and semantic dimension of faith as manifested within the narratives of the Old Testament. Thus, many biblical and theological articles do not dedicate any comments or references to the qal conjugation of the verb

as having no significance under the theological and semantic dimension of faith as manifested within the narratives of the Old Testament. Thus, many biblical and theological articles do not dedicate any comments or references to the qal conjugation of the verb  .16

.16

Following this line of thought, the reader could infer from this predominant academic line of thought the nifal and hifil conjugations of  are the original and basic semantic platform upon which the other semantic nuances, manifested in other conjugations of the same verb, find their respective references, e.g., hofal, piel, pual, hithpael, and even qal. Therefore, the complete silence or omission of the qal form of the verb indicates that its meaning could be equal to or equivalent to the meanings expressed in nifal and hifil.

are the original and basic semantic platform upon which the other semantic nuances, manifested in other conjugations of the same verb, find their respective references, e.g., hofal, piel, pual, hithpael, and even qal. Therefore, the complete silence or omission of the qal form of the verb indicates that its meaning could be equal to or equivalent to the meanings expressed in nifal and hifil.

Noticing this deafening silence of the analysis of the verb  in qal in academia, the following logical queries emerged: Is qal identical to nifal and hifil regarding the verb

in qal in academia, the following logical queries emerged: Is qal identical to nifal and hifil regarding the verb  and for this reason is omitted? Do nifal and hifil of

and for this reason is omitted? Do nifal and hifil of  express the primordial meaning of the verb?

express the primordial meaning of the verb?

It is important to acknowledge that the semantic values of one conjugation can be found expressed in other conjugations of the same verb throughout the different semantic nuances that the Semitic authors used in order to express the deep spectrum of their cultural and religious experience. Using this rationale, it is academically imperative to establish with precision the primordial verbal meaning that expresses the basic semantic domain in order to rediscover the elementary meaning manifested in a subtle manner in the different Hebrew verbal conjugations.

In the field of Biblical Hebrew syntax, it is traditionally accepted that the simplest conjugation is qal, which literally means “light”.17 This conjugation conveys the simplest action implied in the verb at the most basic semantic level (Grundstamm). According to this logical path, Joüon and Muraoka affirm that “the derived or augmented conjugations have an expanded form in relation to the simple conjugation, and the action which they express has an added objective modality.”18 These same authors affirm that the nifal is “the reflexive conjugation of the simple action”19, implying that the same semantic level of qal remains in a certain manner but under a different aspect.

The hifil, on the other hand, is the active conjugation of causative action.20 The hifil generally has to do with the causing of an event and as a consequence, “the object participates in the event denoted by the verbal root”.21 Therefore, following the logic of Joüon and Muraoka, the semantic values expressed in the simple conjugation, qal, are implied in the nuances and modalities expressed in the derived or augmented conjugations; even though the other binyanim can adopt different semantic connotations, such semantic mutations do not necessarily imply that the meaning of the Grundstamm completely disappears from the other conjugations. This elucidation is therefore limited to the study of the lexeme  as an exploratory way to re-discover the semantic value of its qal connotations that can serve as a hermeneutical key to re-interpret the traditional translations manifested in nifal and hifil without denying their particular semantic notions of faith and trust.22

as an exploratory way to re-discover the semantic value of its qal connotations that can serve as a hermeneutical key to re-interpret the traditional translations manifested in nifal and hifil without denying their particular semantic notions of faith and trust.22

Consequently, it is possible to affirm that in the case of the root  , the basic notions remain as a semantic substratum under which the variety of nuances utilized by the Semitic authors describe the broad spectrum of his or her religious and cultural experiences. It is for this reason that it is essential to reconsider the significance of

, the basic notions remain as a semantic substratum under which the variety of nuances utilized by the Semitic authors describe the broad spectrum of his or her religious and cultural experiences. It is for this reason that it is essential to reconsider the significance of  in its qal conjugation as a manner to rediscover its primordial meaning.

in its qal conjugation as a manner to rediscover its primordial meaning.

The verbal form of the lexeme אמן in qal

The verb  in its qal conjugation appears only in active participle in feminine as well as in masculine.23 Each time that the verb appears in its simple active conjugation (qal) it is incorporated into a paternal or maternal context. Generally, the term is employed in the Masoretic Text to describe men and women in charge of the care of babies, children, or dependent beings. The verb in its simplest form (qal) can also be translated as to nourish, to nurture, to feed, to sustain, to cover, to protect, to care, to keep safe and secure.

in its qal conjugation appears only in active participle in feminine as well as in masculine.23 Each time that the verb appears in its simple active conjugation (qal) it is incorporated into a paternal or maternal context. Generally, the term is employed in the Masoretic Text to describe men and women in charge of the care of babies, children, or dependent beings. The verb in its simplest form (qal) can also be translated as to nourish, to nurture, to feed, to sustain, to cover, to protect, to care, to keep safe and secure.

However, the Masoretic Text exclusively presents the verb  in participle qal conveying the meaning of “nurse, custodian, or protector” of a baby or infant as it can be seen in Num 11,12 (

in participle qal conveying the meaning of “nurse, custodian, or protector” of a baby or infant as it can be seen in Num 11,12 ( , the nurse), Isa 49,23 (

, the nurse), Isa 49,23 ( your guardians), Ruth 4,16 (

your guardians), Ruth 4,16 ( , nurse), 2Sam 4,4 (

, nurse), 2Sam 4,4 ( , nurse), 2Kgs 10,1.5 (

, nurse), 2Kgs 10,1.5 ( , protectors, guardians), and Esther 2,7 (

, protectors, guardians), and Esther 2,7 ( , foster father/protector).24 This means that the verb used in masculine and feminine throughout pericopes traditionally placed before, during, and after the Babylonian exile, signifies the proper care and concern by a father, mother, guardian, or nurse who have the responsibility of protecting and shielding children precisely because they are vulnerable and weak creatures, incapable of self-sustaining. This pragmatic notion becomes the essential premise for cognitive linguistics which ascertains that “meaning is grounded in the shared human experience of bodily existence. Human bodies give us an experimental basis for understanding a wealth of concepts”.25

, foster father/protector).24 This means that the verb used in masculine and feminine throughout pericopes traditionally placed before, during, and after the Babylonian exile, signifies the proper care and concern by a father, mother, guardian, or nurse who have the responsibility of protecting and shielding children precisely because they are vulnerable and weak creatures, incapable of self-sustaining. This pragmatic notion becomes the essential premise for cognitive linguistics which ascertains that “meaning is grounded in the shared human experience of bodily existence. Human bodies give us an experimental basis for understanding a wealth of concepts”.25

The text of Num 11,1226, for example, describes the supplication of Moses to YHWH, which reflects an intimate maternal relationship. The episode shows the people of Israel as a burden, like capricious children and whimsical infants, offering the rhetorical questions of “Did I conceive all these people? Did I give them birth?”27 on the lips of Moses. The reader can then add another rhetorical question implicit in the argumentation of Moses: Who is the mother? Certainly, it is not Moses but YHWH himself. Even though Moses is the leader of Israel, he is not responsible for the maternal nourishment and care of the people.28 Only YHWH is the one who has conceived ( ) and gave birth (

) and gave birth ( ) to the people. For this reason, Yhwh must take care of the people as a nurse or protective mother (

) to the people. For this reason, Yhwh must take care of the people as a nurse or protective mother ( ).29 The qal participle

).29 The qal participle  used is in masculine, but its semantic value that is determined by the context, is what expresses the behavioral pattern of a mother.30

used is in masculine, but its semantic value that is determined by the context, is what expresses the behavioral pattern of a mother.30

The passage of Isa 49,2331 ( ) presents an important distinction between the plural qal participle

) presents an important distinction between the plural qal participle  and the feminine noun

and the feminine noun  . The Deutero-Isaian oracle presents the role of the kings as the guardians- protectors while the princesses will become the wet-nurses, namely, those who breast-feed the infants. The passage of Isa 49,23 is part of the pericope of Isa 49,14-26. The theological content of the prophetic text expresses family relations through maternal vocabulary, as it can be seen in expressions like “can a woman forget her sucking child? (

. The Deutero-Isaian oracle presents the role of the kings as the guardians- protectors while the princesses will become the wet-nurses, namely, those who breast-feed the infants. The passage of Isa 49,23 is part of the pericope of Isa 49,14-26. The theological content of the prophetic text expresses family relations through maternal vocabulary, as it can be seen in expressions like “can a woman forget her sucking child? ( Isa 49,15 JPS32) or “she should not have compassion on the son of her womb?” (

Isa 49,15 JPS32) or “she should not have compassion on the son of her womb?” ( Isa 49,15 JPS). The relationship between a mother and her child becomes the metaphor to express the profound bond of YHWH with his people.33

Isa 49,15 JPS). The relationship between a mother and her child becomes the metaphor to express the profound bond of YHWH with his people.33

The prophetic poem presents the figure of a mother (Sion) who is unprotected and abandoned. In her despair, she invoked YHWH (Isa 49,14) who replies as a empathic mother who cannot forget and abandon her own children (Isa 49,15). The oracle’s divine answer is developed through images of care, nourishment, and restoration corresponding to that of a maternal love that radically changed the humiliating situation of the exiles. After experiencing the destruction of Jerusalem and the people of Israel are forced to leave their land, Isa 49,23 describes their drastic transformation through their exile. The peripeteia of the event is described by the adoption of the kings of the nations who become their guardians and protectors (qal participle  ), assuming the role of foster fathers of Israel in its return to Sion. The highpoint of the peripeteia is the moment when the foreign kings prostrate in front of Israel, symbolizing their humiliation and servitude.34

), assuming the role of foster fathers of Israel in its return to Sion. The highpoint of the peripeteia is the moment when the foreign kings prostrate in front of Israel, symbolizing their humiliation and servitude.34

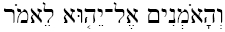

The verb  in qal, used in feminine or masculine participle, also signifies the notion of a leader, mentor, and educator of a child or youth who embraces the role of a father and a mother simultaneously. The reader can observe this meaningful connotation in the behavioral pattern of Mordecai. He adopted the orphan Esther as is depicted in Esther 2,7:

in qal, used in feminine or masculine participle, also signifies the notion of a leader, mentor, and educator of a child or youth who embraces the role of a father and a mother simultaneously. The reader can observe this meaningful connotation in the behavioral pattern of Mordecai. He adopted the orphan Esther as is depicted in Esther 2,7:  . The narrator uses the participle

. The narrator uses the participle  that can be translated as foster father/protector or “the one who brings up.” The term

that can be translated as foster father/protector or “the one who brings up.” The term  describes Mordecai, in this particular context, with the characteristics of a paternal pedagogue who also exercises the cares of a mother.35 When Mordecai becomes the foster father of Esther, he also assumes the double responsibility of parental protection and didactic formation of the child.

describes Mordecai, in this particular context, with the characteristics of a paternal pedagogue who also exercises the cares of a mother.35 When Mordecai becomes the foster father of Esther, he also assumes the double responsibility of parental protection and didactic formation of the child.

For this reason Gesenius suggests that the Greek παιδαγωγός is the most appropriate term to translate  in this context.36 This episode is a good example towards the end of Babylonian exile37 where the objective semantic level of paternal and maternal care-protection acquires a nuanced meaning of education and formation.38 The semantics of qal evolves in its renditions throughout the nuanced notions derived from its basic meaning or basic experiential domain.

in this context.36 This episode is a good example towards the end of Babylonian exile37 where the objective semantic level of paternal and maternal care-protection acquires a nuanced meaning of education and formation.38 The semantics of qal evolves in its renditions throughout the nuanced notions derived from its basic meaning or basic experiential domain.

In the passage of Esther 2,20, the narrator affirms that Esther followed Mordecai’s instructions while she was under his “care” ( ). The feminine Hebrew noun

). The feminine Hebrew noun  describes Mordecai’s nourishment and education. Generally, this term can also be translated as care, tutelage, guidance, custody, oversight, and protection. All these semantic implications are simultaneously implied in this Hebrew noun, which derives from the qal of the root

describes Mordecai’s nourishment and education. Generally, this term can also be translated as care, tutelage, guidance, custody, oversight, and protection. All these semantic implications are simultaneously implied in this Hebrew noun, which derives from the qal of the root  and embodies the same semantic value of the qal participle used in Esther 2,7 (

and embodies the same semantic value of the qal participle used in Esther 2,7 ( ).39

).39

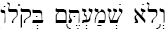

Another example of the usage of the verb in qal expresses the basic care and custody that one may offer to a child: “Jehu sent to Samaria, to the authorities of the city, to the elders and to the guardians ( ) of Ahab’s children” (2Kgs 10,1).40 Jehu’s intention is to exterminate the royal lineage of Ahab and accordingly he sent instructive letters to three groups of characters: the leaders and the elders who represent the authority, and the guardians (protectors-tutors:

) of Ahab’s children” (2Kgs 10,1).40 Jehu’s intention is to exterminate the royal lineage of Ahab and accordingly he sent instructive letters to three groups of characters: the leaders and the elders who represent the authority, and the guardians (protectors-tutors:  ) who are the inner and most intimate group of the royal family. They protect and raise the future bloodline, acting as foster-parents (parental dimension) and paidagogoi (didactic dimension). The

) who are the inner and most intimate group of the royal family. They protect and raise the future bloodline, acting as foster-parents (parental dimension) and paidagogoi (didactic dimension). The  should guard and educate the princes with the attention and discipline implied in the future royal responsibilities of a monarch.41

should guard and educate the princes with the attention and discipline implied in the future royal responsibilities of a monarch.41

The passage of Ruth 4,16 maintains the same semantic line.42 The verse says: “…and Naomi, taking the child, held him to her breast; and it was she who looked after him ( )”. It is essential to clarify that in this context the feminine participle

)”. It is essential to clarify that in this context the feminine participle  does not signify a wet-nurse or a nurse who feeds with her breast milk. Naomi’s age would not allow it, and for this kind of function the author would use the more appropriate feminine participle of

does not signify a wet-nurse or a nurse who feeds with her breast milk. Naomi’s age would not allow it, and for this kind of function the author would use the more appropriate feminine participle of  (breast-feeder) from the verb

(breast-feeder) from the verb  (to breast-feed). It would be erroneous to deduce that the latter verb is a synonym of

(to breast-feed). It would be erroneous to deduce that the latter verb is a synonym of  according to the similarity of maternal contexts. Naomi assumes the responsibility of raising a child according to a maternal and pedagogical dimension.43

according to the similarity of maternal contexts. Naomi assumes the responsibility of raising a child according to a maternal and pedagogical dimension.43

Following the semantic line of the qal conjugation manifested in the afore-mentioned texts, one can deduce that the primordial meaning of the verb  is “to take care and guide responsibly,”44 or “to protect, to nurture, and to educate.”45 Therefore, the most primeval semantic level of

is “to take care and guide responsibly,”44 or “to protect, to nurture, and to educate.”45 Therefore, the most primeval semantic level of  in qal is not identical with the meanings expressed in nifal and hifil because “in forma qal non apparet significatio credendi”46. Therefore, the nifal and hifil assumed and evolved theological and cognitive meanings are built from the basic meaning expressed in qal. Using the terminology of cognitive semantics, the embodied notions of qal become the point of reference to construe the ontological metaphors of faith, trust, and belief implied in the nifal and hifil.47

in qal is not identical with the meanings expressed in nifal and hifil because “in forma qal non apparet significatio credendi”46. Therefore, the nifal and hifil assumed and evolved theological and cognitive meanings are built from the basic meaning expressed in qal. Using the terminology of cognitive semantics, the embodied notions of qal become the point of reference to construe the ontological metaphors of faith, trust, and belief implied in the nifal and hifil.47

The qal conjugation, being the simplest in the Hebrew verbal system, has the value of being the most basic conjugation in comparison with other binyanim. This implies that qal expresses the most fundamental semantic value of the Hebrew root . This statement is found in the philological studies and analysis of Paul Joüon and Takamitsu Muraoka. The other conjugations, like nifal and hifil, derive from the most basic verbal conjugation of qal by way of augmentatives forms through the additions or changes of prefixal and suffixal elements, acquiring different nuances and modalities of meaning built upon the basic semantic value expressed in qal.48 On this matter, Joüon and Muraoka affirm in the following statement:

The Hebrew verb comprises a number of conjugations: a simple conjugation, called qal (light) and a number of derived or augmented conjugations. The simple conjugation is well named because, in comparison with the others, its form is the simplest and the action which it expresses is equally simple [...]. The derived or augmented conjugations have an expanded form in relation to the simple conjugation, and the action which they express has an added objective modality.49

The nuances that are usually translated as to trust, to believe, to be faithful, certain, reliable, stability, etc., are embraced in the nifal and hifil forms together with the substantive forms of the same root, but the basic spectrum of semantic notions flourish from the primary notion expressed in qal. This means that one may trust and believe in somebody else because he or she protects, cares, guides, and behaves as a mother or a father. The notions of security, trust, stability, and fidelity become manifestations of the fundamental act of a parental love and care that cannot reject or abandon its children.50

Portraying the verbal form of אמן in nifal through the semantic notion of qal

The nifal conjugation of  expresses the reflexive or passive dimensions of the simplest action or verbal conjugation which is qal.51 The binyan nifal of

expresses the reflexive or passive dimensions of the simplest action or verbal conjugation which is qal.51 The binyan nifal of  predominantly appears in the Masoretic Text in participle: approximately 32 times, with five presences in the perfect tense, and eight recurrences in the imperfect.52

predominantly appears in the Masoretic Text in participle: approximately 32 times, with five presences in the perfect tense, and eight recurrences in the imperfect.52

The text of Isaiah 60,4 encompasses an important significance for the present study. The verb is used in a passive or reflexive form, having the same semantic value of qal. This is one instance in which it is evident to perceive the same basic meaning of qal in the nifal. The verb  has the maternal connotations of a person who is taking care of children: “Lift up your eyes and look around: all are assembling and coming towards you, your sons coming from far away and your daughters being carried (

has the maternal connotations of a person who is taking care of children: “Lift up your eyes and look around: all are assembling and coming towards you, your sons coming from far away and your daughters being carried ( ) on the hip.” This action embraces the notion of covering-embracing the baby with extreme care, i.e., being very close to the person’s body. The purpose of the statement describes the care in bringing the children to his or her mother.

) on the hip.” This action embraces the notion of covering-embracing the baby with extreme care, i.e., being very close to the person’s body. The purpose of the statement describes the care in bringing the children to his or her mother.

It is important to highlight the semantic field of parental protection in nifal because it is not often mentioned in the philological analysis of specialized lexicons as the ones aforementioned. The reason for this tendency is the emphasis made on the predominant semantic connotations of “to believe, to trust, or to be faithful.” Thus the pericope of Isa 60,4-9, describes Zion glorified by a people who will be accepted as the Lord’s worshippers53, portraying the basic qal connotation manifested in nifal in a post-exilic literature.54 The Trito-Isaiah (chapters 56-66) expresses a more universal and inclusive theological reflection due to the circumstances of the people of Israel who have been facing problems of faith after experiencing their exile.55

The paternal and maternal notions, however, remain as the basic semantic substratum which expresses the primary meaning of the verb, which is the action of covering, taking care, and protecting. This typical parental attitude toward an innocent creature resides as the basic platform of the action to believe at its primeval semantic notion. This semantic cross-domain mapping is the cognitive process of creating an ontological metaphor in which one takes a concept formed from a human parental experience (personal physical space) serving as a source domain for metaphors of faith and trust which are the abstractions or conceptualization of theological notions to develop.56 One person has faith or may come to believe in another person because one has the experience that the other is reliable, firm, secure, and faithful. From that experience one has the certainty that the other person will protect and guide the one who is defenseless.

Keeping in mind this connotation, the reader can then apply the same semantic nuance of the studied verb to a theological field in which the people of Israel have similar experiences with God. This means that Israel believes (meaning in nifal and hifil) in God because Israel already knows through its own history that YHWH has protected them like a mother and father (meaning in qal). The relationship that exists between God and Israel manifests the same dynamics of a familial relationship between parents and children at its more basic core values. For this reason it would be a mistake to omit or reject the analysis of these basic semantic connotations of qal manifested in the other conjugations.57

The term  (nifal) embraces a variety of meanings that generally can be translated into English using the terminology of being firm, being secure, to be trusted, and to be faithful. From these verbal forms other adjectives and substantives derive, e.g., “secure, stable, faithful, belief, security, trust, and fidelity.” For this reason, Moberly identifies the semantic connotations of

(nifal) embraces a variety of meanings that generally can be translated into English using the terminology of being firm, being secure, to be trusted, and to be faithful. From these verbal forms other adjectives and substantives derive, e.g., “secure, stable, faithful, belief, security, trust, and fidelity.” For this reason, Moberly identifies the semantic connotations of  (nifal) as synonymous to ʼemet y ʼemûnâ.58 When the lexeme is applied to a very specific person in the Old Testament, the indicated personage manifests the same characteristics of security and stability immersed in a dimension of fidelity.59

(nifal) as synonymous to ʼemet y ʼemûnâ.58 When the lexeme is applied to a very specific person in the Old Testament, the indicated personage manifests the same characteristics of security and stability immersed in a dimension of fidelity.59

The verb often is translated as “to be faithful”, which has become the stereotypical meaning of this verb in nifal, as one can see in the pericope of 1Sam 22,1460: “...of all those in your service, who is more loyal ( ) than David, son-in-law to the king, captain of your bodyguard, honoured in your household?’”. The pericope of 1Samuel has a double implication. One is the presentation of David as a person who has high qualities, namely, David as being incomparable and superior to all the servants of King Saul, because he possesses like no other the quality of

) than David, son-in-law to the king, captain of your bodyguard, honoured in your household?’”. The pericope of 1Samuel has a double implication. One is the presentation of David as a person who has high qualities, namely, David as being incomparable and superior to all the servants of King Saul, because he possesses like no other the quality of  . The second implication expresses a judicial argument on behalf of David who is not regarded in high esteem by King Saul. In both cases the term

. The second implication expresses a judicial argument on behalf of David who is not regarded in high esteem by King Saul. In both cases the term  embraces the dimension of innocence and fidelity together with the intention of exultation of the personage.61

embraces the dimension of innocence and fidelity together with the intention of exultation of the personage.61

The verb in nifal usually appears in judicial contexts in which it is necessary to have the participation of truthful and reliable witnesses. This means that the moral quality implied in the verb guarantees the certainty of the truth manifested by those who exemplify this characterization. This connotation is significant because the root  is closely interconnected with the notion of truth. The Hebrew noun employed to signify the idea of truth is

is closely interconnected with the notion of truth. The Hebrew noun employed to signify the idea of truth is  which is precisely derived from the root

which is precisely derived from the root  . Consequently the substantive which belongs to the same philological field (Wortfeld) of the root

. Consequently the substantive which belongs to the same philological field (Wortfeld) of the root  , can be translated as firmness, security, trust, stability, and solidity.62

, can be translated as firmness, security, trust, stability, and solidity.62

The same semantic spectrum, when applied to God, acquires a richer value by way of analogy. When God becomes the subject of the verb, multiple semantic levels interplay simultaneously in the narrative, so that the term expresses a rich polysemy that cannot be adequately articulated in any other translation. Hence, modern translations only offer or reflect one single dimension of the polysemy. In the Masoretic Text, the person of YHWH is essentially described with the notion of  that can be translated as faithful and constant (

that can be translated as faithful and constant ( ). The nature of the Lord is secure, stable, reliable, and truthful. Those are essential qualities of his essence and for this reason Israel can trust in him because his nature is to be

). The nature of the Lord is secure, stable, reliable, and truthful. Those are essential qualities of his essence and for this reason Israel can trust in him because his nature is to be  .63

.63

The nifal participle with this specific theological connotation appears very few times in the Masoretic Text describing the nature of YHWH. The three most important passages in which the term appears describing the natura Dei are Deut 7,9; Isa 49,7, and Jer 42,5.64

The Deuteronomistic theology does not admit any flaws in the representation of YHWH in its narratives.65 For the Deuteronomistic author, the essence of YHWH is  , which also indicates that God is the primordial source of trust, protection, nurturing, and security. Therefore, any manifestations of the connotations embraced in the Wortfeld of

, which also indicates that God is the primordial source of trust, protection, nurturing, and security. Therefore, any manifestations of the connotations embraced in the Wortfeld of  , have their own origin and supreme manifestations in YHWH himself. This also means that all the manifestations of the verb

, have their own origin and supreme manifestations in YHWH himself. This also means that all the manifestations of the verb  —in all its conjugations— express and describe the essence of YHWH. All of YHWH’s personal revelations through the Old Testament narratives essentially define the notion of faith which implies fidelity, security, trust, protection, and truth because all of them come from the paternal and maternal love of YHWH who never abandons his own children. The pericope of Deut 7,9 embraces these theological notions.66

—in all its conjugations— express and describe the essence of YHWH. All of YHWH’s personal revelations through the Old Testament narratives essentially define the notion of faith which implies fidelity, security, trust, protection, and truth because all of them come from the paternal and maternal love of YHWH who never abandons his own children. The pericope of Deut 7,9 embraces these theological notions.66

The text describes this essential detail of YHWH’s nature that is interconnected with his being  in the performance of his covenant. This fundamental characteristic expressed with the notion of

in the performance of his covenant. This fundamental characteristic expressed with the notion of  , can be translated as goodness, gentleness, and affection that also connotes stability and love. According to this divine love (

, can be translated as goodness, gentleness, and affection that also connotes stability and love. According to this divine love ( ), God chooses Israel not because of the merits and high moral standards of the people but because his choice comes from his pure divine initiative. The divine selection, then, is based on his

), God chooses Israel not because of the merits and high moral standards of the people but because his choice comes from his pure divine initiative. The divine selection, then, is based on his  and divine promise offered to Israel’s ancestors (see Deut 7,7-8). The experience of security by Israel is pragmatic in the person of God who always manifests himself through concrete deeds done throughout Israel’s history, revealing a relationship of constant love and interaction with his people. This choice implies the proper responsibilities and obligations through an exclusive relationship, in which every single party must keep himself faithful to the stipulations implied in the covenant.67

and divine promise offered to Israel’s ancestors (see Deut 7,7-8). The experience of security by Israel is pragmatic in the person of God who always manifests himself through concrete deeds done throughout Israel’s history, revealing a relationship of constant love and interaction with his people. This choice implies the proper responsibilities and obligations through an exclusive relationship, in which every single party must keep himself faithful to the stipulations implied in the covenant.67

For this reason, the obedience of Israel to the divine law (Torah and mitzvoth) becomes the concrete and existential dimension in which the communion with God is experienced and established. The great faults and unfaithfulness of Israel towards YHWH provoked his righteous retribution because God is always faithful. Therefore, he has to punish his children as a paidagogos has to discipline the children under his care. His didactic behavior does not come out of rage but out of love so Israel can learn from its own mistakes. In this manner YHWH continues to manifest his fidelity and goodness towards those who come to establish a personal relationship of love with him.

The book of the prophet Isaiah also applies the same semantic connotation when the sacred author talks about the fidelity of YHWH towards the one who has been rejected and marginalized. The figure of the servant of the Lord68 embodies this theological connotation in the book of the Deutero-Isaiah: “YHWH who is faithful ( )” (Isa 49,7). Verse 7 presents difficulties in its translation because of the obscurity of the verbal forms in the manuscripts of better textual tradition.69 The Hebrew verse can be structured in two main parts. The first part is the voice of the narrator that introduces the divine utterance (7a). The second part is the divine proclamation addressed to the person that is known in the tradition as the servant of YHWH (7b). The thematic and theological content of the verse seems a paraphrase of the fourth canticle of the servant of the Lord in Isa 52,13-15.70

)” (Isa 49,7). Verse 7 presents difficulties in its translation because of the obscurity of the verbal forms in the manuscripts of better textual tradition.69 The Hebrew verse can be structured in two main parts. The first part is the voice of the narrator that introduces the divine utterance (7a). The second part is the divine proclamation addressed to the person that is known in the tradition as the servant of YHWH (7b). The thematic and theological content of the verse seems a paraphrase of the fourth canticle of the servant of the Lord in Isa 52,13-15.70

The verse follows the same narrative and theological pattern of humiliation of the servant who ultimately would be acknowledged by all the kings and exalted by God himself who according to his divine nature is faithful ( ), namely, trust worthy because he did not abandon his servant. Verse 8 of the same chapter offers a theological explanation of the behavior of God described already with the term

), namely, trust worthy because he did not abandon his servant. Verse 8 of the same chapter offers a theological explanation of the behavior of God described already with the term  in 49,7b. Therefore, Verse 8 is an epexegetical description of what it truly means to be faithful (

in 49,7b. Therefore, Verse 8 is an epexegetical description of what it truly means to be faithful ( ) according to the nature of YHWH. This elucidation is not based upon theoretical and abstract notions but on the tangible experiences of the existential reality of the person who is suffering, namely the servant. That is why Verse 8 in its description talks about the answer of God, the salvation, the help, and the restora- tion of the one who was previously rejected and marginalized.71 The divine intervention has the peripeteic purpose. YHWH transforms the situation of the suffering servant so he can become an instrument of restoration for the people.

) according to the nature of YHWH. This elucidation is not based upon theoretical and abstract notions but on the tangible experiences of the existential reality of the person who is suffering, namely the servant. That is why Verse 8 in its description talks about the answer of God, the salvation, the help, and the restora- tion of the one who was previously rejected and marginalized.71 The divine intervention has the peripeteic purpose. YHWH transforms the situation of the suffering servant so he can become an instrument of restoration for the people.

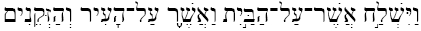

In the pericope of Jer 42,5 ( ), YHWH is invoked as the truthful and faithful witness. The qualification of his nature is expressed by the sacred author as if God would be the only person to have the absolute essence of the attributes of

), YHWH is invoked as the truthful and faithful witness. The qualification of his nature is expressed by the sacred author as if God would be the only person to have the absolute essence of the attributes of  . The described properties, according to the theological mindset reflected in the book of Jeremiah, are fundamental qualities of the natura divina Dei. Hence, in this particular narrative context, the expression

. The described properties, according to the theological mindset reflected in the book of Jeremiah, are fundamental qualities of the natura divina Dei. Hence, in this particular narrative context, the expression  has a very exclusive characteristic because no human being can possess in an absolute manner the attributes of

has a very exclusive characteristic because no human being can possess in an absolute manner the attributes of  in his or her ontological nature.72

in his or her ontological nature.72

Portraying the verbal form of אמן in hifil through the semantic view of qal

The causative conjugation called hifil

73 predominates in the Wortfeld of the root  . The hifil form of the verb appears 52 times, expressing the meaning of security and stability that commonly is translated as “to trust”. The LXX translates the verb

. The hifil form of the verb appears 52 times, expressing the meaning of security and stability that commonly is translated as “to trust”. The LXX translates the verb  45 times, out of the 52 presences in the Masoretic Text, with the verb πιστεύω-πιστεύειν, and five times with the verb ἐμπιστεύω.74

45 times, out of the 52 presences in the Masoretic Text, with the verb πιστεύω-πιστεύειν, and five times with the verb ἐμπιστεύω.74

The hifil of  implies the semantic idea of “to say amen with conviction to all its implied existential consequences”.75 This means that the verbal connotation implies the acknowledgment that the person who speaks or the object of the conversation-affirmation are considered secure, stable, and reliable, meaning that they are true since there is no doubt that they do not exist. The most common translation for this verbal conjugation is “to believe” or “to trust” because these English verbs embrace the acceptance and acknowledgment that the other person (or object) is authentic and infallible.76 But is it possible to discover the basic meaning of qal in the theological connotation of

implies the semantic idea of “to say amen with conviction to all its implied existential consequences”.75 This means that the verbal connotation implies the acknowledgment that the person who speaks or the object of the conversation-affirmation are considered secure, stable, and reliable, meaning that they are true since there is no doubt that they do not exist. The most common translation for this verbal conjugation is “to believe” or “to trust” because these English verbs embrace the acceptance and acknowledgment that the other person (or object) is authentic and infallible.76 But is it possible to discover the basic meaning of qal in the theological connotation of  in hifil? My proposal continues to be a positive respond.

in hifil? My proposal continues to be a positive respond.

Regarding this query, Walther Eichrodt presents a significant observation that states that the hifil can be properly translated as “to consider firm, trustworthy, to find to be reliable” as way to positively describe the relationship with God. But he also affirms that “since the basic meaning of the root ’mn in Arabic is to be secure, out of danger, one could choose as the preferable translation of the Hebrew he’emin, to regard as assured, to find security in”.77 Eichrodt recognizes the semantic notion of qal implied in the hifil form but through its Arabic parallel, indicating that the hifil of “to trust and to believe” implies the notion of protection, care, and security expressed in qal.

can be properly translated as “to consider firm, trustworthy, to find to be reliable” as way to positively describe the relationship with God. But he also affirms that “since the basic meaning of the root ’mn in Arabic is to be secure, out of danger, one could choose as the preferable translation of the Hebrew he’emin, to regard as assured, to find security in”.77 Eichrodt recognizes the semantic notion of qal implied in the hifil form but through its Arabic parallel, indicating that the hifil of “to trust and to believe” implies the notion of protection, care, and security expressed in qal.

An illustrative example of this semantic line is offered in the pericope of Exod 4,1-9.78 The episode describes different signs given by YHWH in order to confirm the authority of Moses ahead of Israel. The recurring use of the root  in hifil is very significant, since it appears a total of five times in nine verses, i.e., 4,1 (

in hifil is very significant, since it appears a total of five times in nine verses, i.e., 4,1 ( ) 4,5 (

) 4,5 ( ) 4,8 (

) 4,8 ( ), (

), ( ) y 4,9 (

) y 4,9 ( ). The verb that traditionally is trans- lated as “to trust,” embraces a more complex theological and social connotation because it expresses a notion that goes beyond the simple act of accepting Moses as a leader. The lexeme conveys the certainty that the leader is trustworthy because God himself has chosen him and has approved his appointment through visible signs. The semeia communicate a phenomenological dimension that leads Israel to the cognition and conviction that YHWH is acting through his leader, Moses.79

). The verb that traditionally is trans- lated as “to trust,” embraces a more complex theological and social connotation because it expresses a notion that goes beyond the simple act of accepting Moses as a leader. The lexeme conveys the certainty that the leader is trustworthy because God himself has chosen him and has approved his appointment through visible signs. The semeia communicate a phenomenological dimension that leads Israel to the cognition and conviction that YHWH is acting through his leader, Moses.79

The usage of  (hifil), applied in a human context, signifies the basic attitude of total trust in which the action of believing is strictly intertwined with the act of trusting, e.g., 1Sam 27,12 (

(hifil), applied in a human context, signifies the basic attitude of total trust in which the action of believing is strictly intertwined with the act of trusting, e.g., 1Sam 27,12 ( ); Prov 26,25 (

); Prov 26,25 ( ); Job 4,18 (

); Job 4,18 ( ).80 In the moments in which a person addresses God using the verb

).80 In the moments in which a person addresses God using the verb  in hifil form, then such information simultaneously expresses a declaration that God, according to his own nature, is essentially

in hifil form, then such information simultaneously expresses a declaration that God, according to his own nature, is essentially  . In other words, it would be the equivalent of professing an “amen” to whatever God is and commands with all the ontological implications that YHWH himself entails. The passages of Exod 14,31(

. In other words, it would be the equivalent of professing an “amen” to whatever God is and commands with all the ontological implications that YHWH himself entails. The passages of Exod 14,31( )81 and Exod 19,9 (

)81 and Exod 19,9 ( )82 illustrate this connotation.

)82 illustrate this connotation.

The reader must observe that the action of believing is certified with the visible deeds (semeia) through the events described in the narrative of Exodus.83 What is the meaning of this? In the transformational process of the strengthening faith of Israel, the wonderful deeds of YHWH are the fundamental proof of his divine existence. The Old Testament describes the personal relationship of Israel with YHWH —and vice a versa—through the unfolding events of the human history that are interpreted and experienced through the eyes of the Israelite spirituality.

That faith, resulting from the historical manifestations of YHWH, becomes a certain “knowledge” (scientia) that God truly exists and acts on behalf of his people, protecting them as a father and mother simultaneously. God is consequently genuine, true, and undisputable in the theological Israelite mindset. Faith is a kind of cognition or knowledge that comes as a consequence of a personal experience of God who interacts with his own people. This assertion indicates that faith is a scientia Dei.

The Old Testament does not describe faith according to epistemological definitions of the Western philosophical mindset. Faith, in the first Testament, embraces concrete and pragmatic conceptions that came out of the experiences of God’s deeds on behalf of his people. It is a phenomenological understanding of faith that implies the complete abandonment into the hands of God who is as certain and reliable as parents are for their children.84 The liberation from Egypt, for example, is a concrete proof of the firmness and veracity of YHWH. Each act of his divine salvation in the Old Testament offers a corroboration of the infallibility of YHWH.85

Another illustrative example of this line of thought is given by the comments of Von Rad when he analyzes the faith of Abraham, in Gen 15,6. The post-exilic text uses the verb in hifil ( ), meaning “to have faith or to believe” which is the typical connotation of

), meaning “to have faith or to believe” which is the typical connotation of  in hifil

86. However, Von Rad proposes as a more appropriate translation of this verb the meaning of “to make oneself secure in YHWH” which is a more common meaning of parental care and protection expressed in the qal conjugation.87 For this reason, the faith in the Old Testament implies the total self giving into the hands of God which is based upon the parental notion of protection, in the same way Abraham did (Gen 15,6), or a defenseless person, like a child must do in putting his or her life into the care of a protector. This also implies that whatever God utters has the certainty that it would be accomplished, according to the basic schema of divine utterance and fulfillment (e.g., Exod 4,1.31; 19,9).

in hifil

86. However, Von Rad proposes as a more appropriate translation of this verb the meaning of “to make oneself secure in YHWH” which is a more common meaning of parental care and protection expressed in the qal conjugation.87 For this reason, the faith in the Old Testament implies the total self giving into the hands of God which is based upon the parental notion of protection, in the same way Abraham did (Gen 15,6), or a defenseless person, like a child must do in putting his or her life into the care of a protector. This also implies that whatever God utters has the certainty that it would be accomplished, according to the basic schema of divine utterance and fulfillment (e.g., Exod 4,1.31; 19,9).

The verb  consequently embraces a complex personal attitude inferring the fear of the Lord, meaning that he certainly exists and is true to his nature (cfr. Isa 8,13). Because of his divine character, his relationship with the people, or with particular individuals, requires obligations and responsibilities that simultaneously are complemented with reverence, awe, trust, and obedience. Dimensions that make Israel feel secure and protected like a child in the arms of his parents. Isa 28,16 illustrates this notion further by emphasizing the imagery of a solid and firm rock that has been tested through time.88

consequently embraces a complex personal attitude inferring the fear of the Lord, meaning that he certainly exists and is true to his nature (cfr. Isa 8,13). Because of his divine character, his relationship with the people, or with particular individuals, requires obligations and responsibilities that simultaneously are complemented with reverence, awe, trust, and obedience. Dimensions that make Israel feel secure and protected like a child in the arms of his parents. Isa 28,16 illustrates this notion further by emphasizing the imagery of a solid and firm rock that has been tested through time.88

The “historical dimension” implies the retrospective view that serves to guarantee any person who has placed his/her trust and security in YHWH that no matter what happens the faithful will not be disappointed. Through the historical proof of the past events the faithful have certainty that the same divine behavioral pattern remains constant through time, implying that the same parental activity of God will continue forward into the present time with an implicit eschatological dimension.89

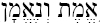

Among their contextual diversities, the Psalms present magnificent pheno- menological expressions of faith that are so practical and realistic that the psalmist has the conviction that whatever God proclaims must be accomplished and fulfilled during his own span of life. The confidence of the psalmist makes him place his faithful trust in YHWH in his present time. An illustrative sample of this theological tradition is Psalm 27,1390 that affirms: “This I believe ( ): I shall see the goodness of Yahweh, in the land of the living.”

): I shall see the goodness of Yahweh, in the land of the living.”

The psalmist utters an absolute belief in YHWH that rejects any possible scenario of accomplishment in the world to come (eschatological dimension). The fulfillment of the divine promises will not be experienced in the future generations but in the present time of the psalmist. Such unconditional certainty does not give any space for the waiting time that is beyond the present vital moment.

The Faith of Israel through the semantic stratum of אמן in qal: conclusions

The conception of  in qal conjugation is exclusively circumscribed within a parental and familial semantic context while at the same time it is the primordial platform of meaning upon which the other conjugations and derived lemmas express their various meanings.91 The original value of the Hebrew verb in qal expresses the care, protection, nourishment, sustenance, and embracing of a parent for his/her children. Therefore, the cross-domain mapping derived from the fundamental notions implied in qal offers six primordial semantic fields as conceptual integrative lines of meanings:

in qal conjugation is exclusively circumscribed within a parental and familial semantic context while at the same time it is the primordial platform of meaning upon which the other conjugations and derived lemmas express their various meanings.91 The original value of the Hebrew verb in qal expresses the care, protection, nourishment, sustenance, and embracing of a parent for his/her children. Therefore, the cross-domain mapping derived from the fundamental notions implied in qal offers six primordial semantic fields as conceptual integrative lines of meanings:

Family relationship as the source domain semantic experience. The parents are the protectors, nurturers, educators, and guardians of the children who are defenseless and incapable of self-sustaining. The family relationship that embraces all these responsibilities is based on love. The extended notion of family also implies that the same aforesaid responsibilities are performed by the grandparents and all the members of the extended family, typical of the ancient Semitic mindset. The family bond becomes a source of identity for their members, connotation that describes the theological and spiritual relationship of YHWH with Israel manifested in the Old Testament.

Attitude of protection. It is motivated by the love of a mother or father for their children. The same behavior can be performed by a mentor, guardian, or nurse. The level of protection increases according to the intensity of the personal relationship. It is a semantic notion derived from the family relationship. The same semantic profile is embraced in the relationship of YHWH with Israel through the experience of the Exodus, wandering in the desert, and throughout the Babylonian exile.

Attitude of nourishment. It is motivated by the proper love and care of the pa- rents. The ones responsible for raising children feel compelled to nurture them in order to sustain and preserve their lives in the best way possible. It is a semantic notion derived from the family relationship. The same notion is applied to the theological dimension of faith in Old Testament as it is illustrated in the Exodus, Numbers, Psalms, Deutero and Trito Isaiah.

Didactic role. It is appropriate for parents to become the paidagogoi of their children. The education guarantees the preservation of traditions and behavioral patterns that are considered to be righteous. From a theological point of view, YHWH is the paidagogos of Israel.

Sense of security. It is a proper response by children or young persons who come to comprehend this awareness through experiencing security and protection from the one who loves them. It is a pragmatic knowledge through repetitive experiences. Through experiences of hardships, the faithful remnant of Israel finds the courage to persevere through their trust in God. It is a semantic notion derived from the family relationship and the attitude of protection embraced in the meaning of

(qal).

(qal).Historical proof. It is a semantic notion derived from the experience and knowledge of security and protection. Children who become adults would have a solid trust in their parents who always were committed to them. The constant and faithful attitude of protection, nourishment, and teachings of YHWH create a behavioral pattern that proves to be constant in the present and future events. It is a semantic notion derived from the semantic fields of family relationship (a) and the attitude of protection (b). The religious drama of Israel is their lack of anamnesis at the moment of remembering the deeds of YHWH on behalf of his people. However, the sacred hagiographers constantly remind the people of Israel that in the same manner how YHWH freed his people from the slavery and hardships in the past, in the same way YHWH will continue to deliver his faithful people from the hardships of the present and future.92

From a diachronic standpoint, the basic semantic notion of the root  manifested in qal has evolved throughout time. The notion of qal appears in texts that according to their final form can be located from the time of the exile and post-exile, namely, from the Babylonian and Persian periods.93 However, some of these texts may reflect a material or tradition that can be placed between the 8th and 7th century BCE.94

manifested in qal has evolved throughout time. The notion of qal appears in texts that according to their final form can be located from the time of the exile and post-exile, namely, from the Babylonian and Persian periods.93 However, some of these texts may reflect a material or tradition that can be placed between the 8th and 7th century BCE.94

The same line of thought can be appreciated in the use of the basic meaning in its passive form (nifal) in Isa 60,4, indicating that even during the Persian period basic human experiences of parental care and protection are used in the root  even in nifal conjugation. Therefore, the basic semantic cognitive domain remains even though the theological and more abstract notions are being used simultaneously through the same root in nifal and hifil.

even in nifal conjugation. Therefore, the basic semantic cognitive domain remains even though the theological and more abstract notions are being used simultaneously through the same root in nifal and hifil.

The traditional meanings expressed in nifal and hifil predominate in texts that can be placed during the time of the exile and post-exile.95 It is significant the text of Jer 42,5, because its material began to be collected between the seventh and the sixth centuries BCE, thus the ontological notion of  used to describe the nature of YHWH appears as early as pre-exilic times of the Babylonian period or during the transition from the Assyrian to the Babylonian period.96

used to describe the nature of YHWH appears as early as pre-exilic times of the Babylonian period or during the transition from the Assyrian to the Babylonian period.96

If the different meanings of the same root are used at the same time, which one supposes to be the most archaic or basic meaning? From the standpoint of the cognitive linguistics, the notions of qal become the most plausible option. Cognitive linguistics assumes the principle that the basic meaning is embodied, i.e., it is grounded in the vital human experience of corporeal existence.97 The notions of parental care, protection, and nurture are the most basic bodily or corporeal experiences that any human being has since the moment of his/her birth.

This human experience serves as the experiential basis for understanding the more abstract notions of education, discipline, trust, faithfulness, faith, and belief. Therefore, the qal expresses a cognitive source domain from which the sacred authors try to implement their notions into the domain of God and the experience of the relationship existing between YHWH and Israel.98 The basic meaning of qal remains as the substantial human experience that gives rise to a wide variety of abstract and theological connotations that serve as grammatical expressions of experiential faith that implies a parental relationship with God.99

These “semantic lines” give a broader significance to the notions of security, trust, fidelity, and truth expressed in the nifal and hifil of  and its derived forms or cognate substantives. These semantic interrelations between qal and the other forms of the Hebrew root have been neglected and marginalized at a philological and theological level. Through this theological essay I tried to emphasize the parental notion of the care and nourishment of a defenseless child, e.g., Israel, as the basic semantic substratum (source cognitive domain) upon which all the diverse semantic nuances of the verb

and its derived forms or cognate substantives. These semantic interrelations between qal and the other forms of the Hebrew root have been neglected and marginalized at a philological and theological level. Through this theological essay I tried to emphasize the parental notion of the care and nourishment of a defenseless child, e.g., Israel, as the basic semantic substratum (source cognitive domain) upon which all the diverse semantic nuances of the verb  derive, making more evident the personal and exclusive relationship that exists between Israel and YHWH.

derive, making more evident the personal and exclusive relationship that exists between Israel and YHWH.

Therefore, the experience of faith in Israel is based upon a relationship of love with YHWH who is father and mother conjointly. According to this line of thought, one may comprehend all the metaphors and expressions of God’s love as manifested in the Psalms, the nevi’im, and the expressions of faith through Jesus’ parental relationship with his Father as revealed in the writings of the New Testament.100