The current study aimed to explore the underlying reasons that motivated individuals to violate norms stemming from Peruvian government regulations implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. Norms are defined as patterns of behavior shared by members of a society (Allport, 1934), which function as shared expectations of how individuals should behave within it (Katzenstein, 1996). Such norms can emerge spontaneously as a product of shared routine, as well as by design such as through the institutional issuing of laws and rules to govern behavior. Norm transgressions are acts that deviate from those expectations and, in many cases, are subject to some type of formal sanction or social disapproval (Cialdini, 2007). Cialdini et al. (1990) distinguish between prescriptive and descriptive norms. The former refers to the societal expectations for appropriate behavior or what should and should not be done. The latter refers to individuals’ perception of how most people in society actually behave in any given situation.

Throughout Peru’s history there is evidence of a conflictive relationship between citizens and established social norms, partly manifest through the proliferation of transgressive behaviors (Portocarrero, 2005; Quiroz, 2014). Such transgressions are evident across all socio-demographic groups, from the systemic corruption at the highest levels of power to the minor infractions found in citizens’ everyday life (Mujica & Zevallos, 2016; Portocarrero, 2005). To understand these transgressions, it is useful to analyze individuals’ perceptions of the normative system; that is, how people represent and evaluate, from a systemic perspective, the established norms and the institutions and actors in charge of promoting, supporting and monitoring their compliance. It is also useful to analyze the beliefs and actions of citizens regarding the norms, which derive from their relationship with the described system (Beramendi, 2014). Some studies suggest that evaluations of the normative system are tied to perceptions of the system’s legitimacy, perceptions of the transgressive behavior of others, and perceptions of norm strength (Beramendi, 2014; Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014, 2018).

The perception of system legitimacy is related to the perception of fairness in the organization of social institutions and the performance of the authorities within those institutions (Beramendi, 2014). When there is a perception of high legitimacy, people are more likely to be satisfied with the decision-making of these institutions, which, in turn, strengthens the institutional structure (Napier & Tyler, 2008). When there is a perception of low legitimacy, however, the system loses the respect and support of individuals within that system (Tyler, 2001, 2006). Several factors under- mine legitimacy: Poor distribution of resources, lack of procedural justice, and low institutional efficiency, all of which affect trust in institutions (Easton, 1975; Napier & Tyler, 2008). Other associated factors are high levels of corruption and authoritarianism by authorities (Beramendi, 2014; Kluegel & Mason, 2004).

A high perception of transgression can result in a naturalization of non-compliance with the norms. At an individual level, the cause of such transgressive behaviors can depend on the nature of the norm, the societal context, the time or individual characteristics such as moral worldview (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014). If citizens believe that there is widespread evasion of norms by members of a society, then it becomes apparently adaptive to conduct similarly, and transgression becomes normalized (Cialdini, 2007). This process of normalization can also lead to a perception that the authorities, who should, in theory, be role models (e.g., police, public servants, etc.), do not comply with the norms (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2013a). This perception is reinforced by the lack of control and sanctions for non-compliance with both social and institutional norms (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2013b). In Peru, citizens perceive that a large portion of public servants, businessmen, and even religious leaders are involved in acts of corruption at the institutional level (Latinobarómetro, 2018). In addition, bribe payments to authorities, the purchase of “pirated” or illegally sourced products and tax evasion, among other local level transgressions, are still common (Proética, 2019).

The perception of low normative strength refers to situations in which norms are seen as arbitrary and authorities as above them (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014). Where the perception of normative strength is low, norms lose power, as they depend on those who control them instead of being subject to formal processes to verify compliance. In addition, citizens feel that these are imposed on them without considering their needs and realities; therefore, compliance with the norms is seen as difficult (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2013b). This situation results in double standard contexts; that is, a gap between what is expected to be done and what is actually done (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014; Helmke & Levitsky, 2004). The resulting consequences are negative because instead of replacing or complementing the formal system, informal norms challenge the system, which generates uncertainty and weakens institutions (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014, 2018).

A study conducted in Latin American countries, including Peru, found that citizens have a negative perception of their respective regulatory systems (Beramendi et al., 2020). This is supported by a perception that norms are meaningless, as they are imposed on individuals instead of being voluntarily accepted. This is in addition to a view of institutions as not very legitimate and with little power, and a perception of widespread transgression (Beramendi et al., 2020).

However, although, in the Peruvian context, there is a general tendency to perceive the normative system as weak and fragile, evidence suggests that this perception may have variations depending on individuals’ Social Dominance Orientation -SDO- (Gnädinger & Espinosa, 2018; Janos et al., 2018). SDO, as an ideological indicator, denotes the degree to which individuals desire or prefer hierarchical versus egalitarian relationships between groups; that is, attitudes oriented toward the dominance of high-status groups over low-status groups within society (Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius et al., 2004). This reflects, in its most extreme form, a vision of the world as ruthless and competitive, in which struggles for power and control of resources are inevitable (Jost et al., 2009). In this context, individuals who score higher on SDO would express greater desires for power and less empathy, concern and compassion for others (Duckitt, 2001; Son Hing et al., 2007).

Therefore, in societies such as Peruvian, where there is a perception of inequality in expectations around norm adherence, studies suggest that individuals with high SDO perceive a greater legitimacy of the normative system and evaluate it more positively (Gnädinger & Espinosa, 2018; Janos et al., 2018). In such societies, the maintenance of inequality confers those with greater social or economic influence with advantages. As a result of this influence, the privileged members have the capacity to maintain the social hierarchy and structural asymmetry, which enables them to maintain their social advantage. Members thus have a strong self-interest in perceiving the system as “fair” and legitimate (Gnädinger & Espinosa, 2018; Janos et al., 2018). Additionally, research indicates that individuals with higher levels of SDO are more likely to tolerate and engage in transgressive behaviors, especially if norms are presented as impediments to achieving dominance (Janos et al., 2018; Monsegur et al., 2014; Rottenbacher & Schmitz, 2012).

Following the spread of COVID-19 in the early 2020s, most governments worldwide proposed norms restricting individuals’ behavior to minimize contagion (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe [CEPAL], 2020). In Peru, a National State of Emergency was declared in March 2020, which included measures such as mandatory social isolation (quarantine), mandatory social immobilization (curfew), border closure, limitation of people transportation, and mandatory use of masks, among other restrictions (El Peruano, 2020).

In response to these restrictions, a considerable number of citizens were non-compliant. Surveys conducted during the first months of confinement by the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos [IEP] (2020a, 2020b) showed that around one-third of the population believed that, in their neighborhood, there was low compliance with the government-issued norms. In addition, during April 2020 alone, more than 52 000 people nationwide were detained for non-compliance (Redacción Gestión, 2020).

The prevalence of norm non-compliance needs to be socially contextualized. Peru is a country of notable social and economic inequalities where informal work predominates (Cotler & Cuenca, 2011; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI], 2018). In times of crisis, these gaps are aggravated or become more evident (Oxfam Intermón, 2012). In this respect, for many, the greatest threat of the pandemic is not in infection, but in losing their jobs or even not having anything to eat (Amaya, 2020). This is supported by opinion surveys which showed that over a third of the population were more afraid of hunger than of the coronavirus, especially the self-employed and those at lower socioeconomic levels (IEP, 2020a, 2020c, 2020d), and it is precisely these people who showed the greatest disapproval of the then government’s administration (IEP, 2020a). This could be reflecting a perceived lack of legitimacy of the authorities in charge of issuing the norms (Beramendi, 2014; Tyler, 2001, 2006).

Beyond economic shortages and labor market instability, there are several other reasons for norm non-compliance. Beliefs related to the dangerousness of the virus (“the virus only attacks the elderly”), to the veracity of the information (“all this is something put together by the big companies to control us”), and to religious issues (“nothing will happen to me because God protects me”), among others, provide justificatory frameworks for ignoring government mandated norms. This is evidenced in what is expressed by the mass media regarding the outbreak and comments on social networking sites (Gil, 2020; Pizarro et al., 2020).

Several factors emerged that could have influenced the transgression of restrictions put in place by the government. This research sought to describe and analyze the relationship between sdo, the perception of the normative system, trust in institutions, the justification for non-compliance with the norms issued during the covid-19 National Emergency and the self-reported frequency of transgression of these norms.

The research hypotheses proposed in the present study are: (1) SDO will increase self-reporting of norm transgression in this context, (2) negative perception of the normative system will increase self-report of transgression, (3) justifications for non-compliance associated with deprivation and need will increase self-report of transgression.

Method

Participants

A total of 126 participants were recruited for the study. The mean age was 31.19 (SD = 12.40), and 55.6 % identified as male. Of the participants, 73 % reported residing in Lima and 27 % were from other regions of Peru; 19.8 % had a postgraduate degree, 55.6 % had a university degree, 7.9 % had a technical degree, and 16.7 % had a basic level of education, either primary or secondary. 0.8 % considered themselves to be in a high socioeconomic level (SEL), 18.3 % in a medium-high SEL, 61.1 % in a medium SEL, 14.3 % in a medium-low SEL and 5.6 % in a low sel. At the time of the research, 33.3 % were not working, 15.9 % were self-employed and 50.8 % were dependent workers. Inclusion criteria were that participants were Peruvian, residing in Peru at the time of answering the questionnaire, and 18 years of age or older (of legal age).

Variables and Measures

Sociodemographic Data. The following data were considered: sex, age, nationality, place of residence, educational level, self-perceived SEL, and current occupation. Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) (Pratto et al., 1994). The SDO scale measures an individual’s belief in the legitimacy and desirability of a group-based hierarchy. Individuals high in SDO tend to endorse a hierarchical societal structure and social ideologies that contribute to the development or maintenance of such a structure. We used the version adapted and validated by Cardenas et al. (2010) for use in Chile. The scale has 16 items with a Likert-type response format, in which the score ranges from 1 to 6, where 1 = Strongly disagree and 6 = Strongly agree. This version has previously been used in several studies conducted within Peru, finding adequate psychometric properties (Espinosa et al., 2017; Valencia-Moya et al., 2018). In the present study, the scale had good internal consistency for the overall score (α = .84).

Normative System Perception Scale (NSPS) (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014). The scale consists of 20 items, with a Likert-type response format in a score between 1 and 6, where 1 = Strongly disagree and 6 = Strongly agree. This instrument has three dimensions: (1) Perception of Legitimacy (where a higher score implies a perception of better functioning or acceptance of the system), (2) Perception of Transgression (where a higher score indicates a higher perception of non-compliance with norms in society), and (3) Perception of Normative Weakness (where a higher score implies a higher agreement that norms are fragile and do not adequately regulate behavior). In the Peruvian context, this scale has been used in research with samples of adults in the urban sector, in which adequate psychometric properties were evidenced (Beramendi et al., 2020; Janos et al., 2018). For the present research, the following reliability indicators were found for each dimension: Perception of Legitimacy (α = .78), Perception of Transgression (α = .84) and Perception of Normative Weakness (α = .53).

It is worth highlighting the potential for low variability and positive self-representation bias in the responses. This could reduce the internal consistency of the scale. However, a meta-analysis conducted by Mezulis et al. (2004) concluded that it is acceptable to work with internal consistency coefficients as low as .5 without affecting the ability to make statistical inferences. This interpretation criterion was applied to all scales.

Trust in Institutions (World Values Survey, 2010-2014). This instrument measures an individual’s level of trust in the institutions tasked with responding to the COVID pandemic in Peru. For this research, the institutions that played a role in the establishment or control of compliance with norms during the COVID-19 National Emergency in Peru were selected (Armed Forces, National Police of Peru, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Economy, Presidency, Congress, Judiciary and the Media). The response format is a 4-point scale, where 1 = No confidence, 2 = Little confidence, 3 = Some confidence and 4 = Much confidence. For this study, a general indicator of trust in institutions was constructed using the average response score for each of the institutions indicated, which presented adequate reliability (α = .75).

Transgression of the Norms Issued During the National Emergency due to COVID-19. An ad hoc scale was constructed to measure a self-report of the degree of COVID-19-related norm transgression during the period of National Emergency (during the first moment of confinement). This measure used the norms issued in response to the pandemic, published in the COVID-19 section of the virtual version of the newspaper El Peruano (2020). The initial version of this questionnaire had 14 items corresponding to the various norms identified. Participants were required to identify the extent to which they had transgressed these norms in a 5-point scale format, where 1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Frequently and 5 = Always. In addition, the option “Not applicable in my case” was added.

To determine the structure of the scale, an exploratory factor analysis was performed, for which acceptable sample adequacy was obtained accord- ing to the Kayser, Meyer and Olkin [KMO] criterion (KMO = .760; p < .001). The Maximum Likelihood extraction method was used and a Varimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization was applied. Two items were eliminated from the analysis and two dimensions were obtained that explain 40.79 % of the total variance. The first dimension captures transgressive behaviors relating to the norms proposed by the government. This dimension was labeled ‘Non-compliance’ (α = .80) and contains items such as “I have left home during curfew hours.” The second dimension, labeled ‘Compliance’ (α = .56), contains items that indicate norm adherence, such as “I have correctly used the mask in public places”.

Justifications for Non-compliance with the Norms Issued During the National Emergency due to COVID-19. An ad hoc questionnaire was prepared about possible justifications underlying the transgression of the norms measured. For this purpose, we systematically collated accounts given by specialists, opinion leaders, and other citizens on the issue in question from online versions of different newspapers and media circulating in the country, as well as public comments made on social media. This instrument has 14 items, which are answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6, where 1 = Strongly disagree and 6 = Strongly agree.

To determine the structure of the scale, an exploratory factor analysis was performed, for which acceptable sample adequacy was obtained (KMO = .814; p < .001). Again, the Maximum Likelihood extraction method was used and a Varimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization was applied. Two dimensions were obtained that explain 39.96 % of the total variance. The first one, named ‘Irrational beliefs and biases’ (α = .86), refers to the justification of norm non-compliance based on erroneous or poorly grounded ideas about the dangerousness of the virus and the veracity of the information or personal freedom, among others. It has items such as “It is better to go out and create our own defenses against the virus”. The second of the two dimensions, labeled ‘Need-driven transgression’ (α = .65), contains items such as “I have to go out to work because I no longer have money”, which allude to non-compliance resulting from participants’ material or economic situation.

Procedure

A virtual form was developed using the Google Forms platform which contained all the instruments presented in the previous section. It was decided to virtualize the questionnaire because the situation made it difficult to carry out the data collection in person.

Participants were recruited through social media (Facebook and WhatsApp) and email between June 20th and July 16th, 2020; i.e., two months after the period of strict quarantine. The first section of the form required that participants give their informed consent. Here they were informed of the objectives of the research, that their participation would be completely voluntary and anonymous, and that the information they provided would be confidential and only used for academic purposes. No reward or material incentive was offered for participation. Once participants had read the terms of participation, they had the option of checking “Next” as a way of agreeing to participate in the study.

Data Analysis

As discussed above, a factor analysis of the scales of transgression and justification of non-compliance with the norms issued in the context of the National Emergency due to COVID-19 was con- ducted as a criterion for validating the psychometric structure of the scales. In addition, an internal consistency analysis of all the scales and their dimensions was performed.

In the second stage of analysis, descriptive statistics of all the study variables and their dimensions were obtained. Next, correlation analyses were carried out between the study variables. Finally, a path analysis was conducted. Path analysis is a complex statistical approach that helps in the development of the causal interpretation of variable association (Shaughnessy et al., 2012). As a type of analysis from the structural equation model family, path analysis posits causal or hierarchical links between numerous variables, providing a powerful analytical tool for expressing highly complex theories (Ruiz et al., 2010).

Results

Descriptive analyses were implemented, including measures of central tendency and dispersion, to determine the statistical behavior of the study variables. Results for the measure of SDO show a mean score of 2.06 with a standard deviation of 0.75. Given the SDO scale’s mid-point of 3.5, these results suggest, on average, a medium- low preference towards social dominance in the participants.

Descriptive statistics for scores on the perception of the normative system (Table 1) show that there is a tendency in the participants to report high perceived levels of transgression and normative weakness, and low levels of perceived legitimacy of the system, compared to the scale’s midpoint (3.5).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Dimensions of the Normative System Perception Scale

| Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of Legitimacy | 1.94 | 0.72 |

| Perception of Transgression | 5.10 | 0.81 |

| Perception of Normative Weakness | 4.43 | 0.95 |

Results for the general indicator of trust in institutions show, on average, a low level of institutional trust among the participants (M = 2.06; SD = 0.47) given the scale’s midpoint of 2.5. On the scale of justifications for non-compliance with the norms issued during the National Emergency due to COVID-19, given the midpoint of the scale (3.5), descriptive statistics show a medium-low score for both justifications based on irrational beliefs and biases (M = 2.28; SD = 1.02) and justifications based on need (M = 2.81; SD = 1.39).

For the measure of the transgression of norms issued during the National Emergency due to COVID-19, concerning the midpoint of the scale (3), the analysis revealed a high level of average participant compliance (M = 3.97; SD = 1.00) and a low level of average participant non-compliance (M = 1.31; SD = 0.49).

Correlations

Variable correlation analyses were carried out using Pearson’s r statistic. In line with the criteria proposed by Richard et al. (2003) , r < .20 will be considered as a correlation coefficient with a small effect size; r < .30, as a medium effect coefficient, and r ≥ .30, as a large effect coefficient. Table 2 shows in greater detail the relationships between variables observed in this study.

Table 2 Correlation between Study Variables

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SDO | - | .30** | -.25** | -.16* | .03 | .37** | .11 | .16* | -.06 |

| 2. Perception of Legitimacy | - | -.47** | -.36** | .30** | .14 | -.01 | .26** | -.09 | |

| 3. Perception of Transgression | - | .47** | -.02 | .02 | -.15* | -.30** | .14 | ||

| 4. Perception of Normative Weakness | - | -.16* | .18* | -.01 | -.17* | .03 | |||

| 5. Trust in Institutions | - | -.19* | -.12 | -.18* | .03 | ||||

| 6. Irrational Beliefs and Biases | - | .28** | .09 | -.13 | |||||

| 7. Need-Driven Transgression | - | -.01 | -.20* | ||||||

| 8. Non-Compliance | - | .01 | |||||||

| 9. Compliance | - |

These results show that SDO is associated with diverse effect sizes (small, medium, and large) for the three normative system dimensions. Likewise, results show that higher levels of SDO are associated with higher levels of irrational beliefs and biases that justify transgression, as well as self-reports of norm non-compliance, with a large and a small effect, respectively. The latter result supports the first hypothesis of the study: levels of SDO predict self-reporting of norm transgression in this context.

The three dimensions of the normative system perception scale are consistently associated with each other, as expected (see Beramendi, 2014). Specifically, the perception of legitimacy is directly related, with a large effect, to trust in institutions and, with non-compliance, with a medium effect size. Perception of transgression is inversely related, and with a small magnitude, to the justification for need-driven transgression, as well as with a large effect on non-compliance with norms. Perception

of normative weakness is associated, with a small effect, directly with irrational beliefs and biases, and inversely, with trust in institutions and non-compliance. The second hypothesis of the study is not verified at this level: the negative perception of the normative system did not increase the self-report of transgression. Instead, the greater the perception of the deficiency of the normative system, the less non-compliance was reported.

Trust in institutions is inversely related, and with a small magnitude, to irrational beliefs and biases and non-compliance. In turn, irrational beliefs and biases are related to need-driven transgression, with a medium effect, but are not linked to indicators of non-compliance and compliance; while need-driven transgression is inversely associated with compliance, also with a medium effect. This finding confirms the third hypothesis of the study: justifications for non-compliance associated with deprivation and needs increase self-reports of transgression.

Path Analysis

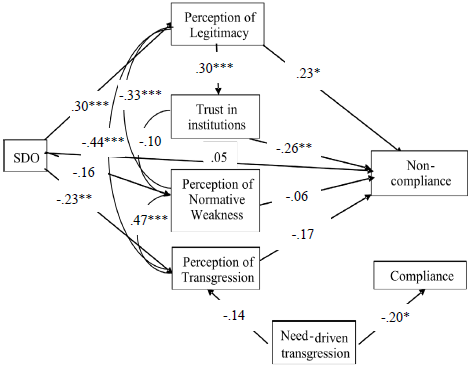

Based on the correlations observed and the literature reviewed, a predictive model of the transgression of norms during the COVID-19 National Emergency was designed (Figure 1). Variables that have a direct or indirect relationship with the non-compliance or compliance dimensions were entered as dependent variables. SDO was placed at the first level of analysis, since, as an ideological indicator, it would frame and prescribe the representation of a system in a more general and abstract way. Given that SDO can be expected to inform individuals’ perceptions of a particular normative system (Janos et al., 2018), these have been placed at the second level of analysis, along with trust in institutions. Then, indicators of system perception would influence the behavioral self-reporting of non-compliance. Finally, need-driven transgression is included as an exogenous variable that influences both the perception of transgression and compliance.

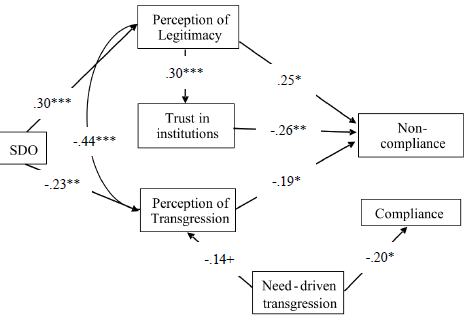

The proposed model presents good levels of fit Chi2/df = .686, CFI = .999, RMSEA = .001, PNFI = .434. However, it was decided to present a second model (Figure 2) in which the associations that turned out to be non-significant were eliminated. First, the effect of perceived normative weakness on non-compliance was discarded. Next, the effect of SDO on non-compliance was eliminated. Finally, the effect of SDO on the perception of normative weakness was eliminated. Thus, the latter variable was dropped from the model. The resulting model presents higher significant associations and good levels of fit Chi2/df = .763, CFI = .999, RMSEA = .001, PNFI = .518.

This second model is presented as a more parsimonious alternative, as it dispenses with the variable perception of normative weakness. This variable makes little contribution to the model as a whole. Despite this change, the model maintains adequate fit indices.

Discussion

The present research sought to describe and analyze the relationships between SDO, dimensions of the perception of the normative system, trust in institutions, justifications for non-compliance with the norms issued during the National Emergency due to COVID-19, and the self-reported frequency of norm transgression.

Peru has been shown to have a long history of low respect for norms (Portocarrero, 2005; Quiroz, 2014). Social psychological research suggests that such transgression is tied to a perception of the low legitimacy of a social system; that is, a system with poor institutional functioning and with little procedural and distributive justice (Beramendi, 2014; Tyler, 2001). In the context of the present research, the descriptive analysis revealed that participants report a higher level of compliance than non-compliance with the norms. This result can be partly explained, by the socioeconomic conditions of the study participants: participants were mostly middle-class with a high level of education and a relatively stable employment status, despite the crisis caused by the pandemic. These characteristics made them less vulnerable to falling into situations of material and economic need, which would have forced them to leave home or engage in activities not allowed in this context (IEP, 2020c). This is reflected in the low levels of need-driven transgression found in this sample. However, the results suggest that compliance was also influenced by a set of psychosocial variables that, depending on their prevalence, will orient the participants to a greater or lesser degree of normative transgression.

On average, participants reported a mediumlow score for SDO. However, at the correlational level, SDO is consistently associated with different perceptions and beliefs that underlie normative non-compliance (Janos et al., 2018), and consistent with the first hypothesis, levels of SDO are also directly related to non-compliance (Rottenbacher & Schmitz, 2012). Furthermore, results from the NSPS suggest that participants, on average, view the normative system negatively; that is, they have a high perception of transgression and normative weakness and a low perception of legitimacy. Results also show a medium-low trust in institutions. Contrary to our second hypothesis (see Beramendi, 2014), these results suggest that a negative perception of the normative system does not increase the predisposition to transgress, as this perception is accompanied by a critical view of citizens’ transgressive behavior in the context of COVID-19. This is discussed in more detail below.

The present research suggests that the effect of justifications for normative non-compliance is greater in the case of need than in the case of irrational beliefs and biases. This result highlights the importance of distributive justice processes within a society as a fundamental element for norm adherence (Du et al., 2020; Tyler, 2006).

The results at the descriptive and correlational level allow us to develop a complex model of relationships that shows two complementary routes that explain (non)compliance during the first moment of confinement due to COVID-19 in Peru. The first one evidences that transgression is the result of the legitimization of a system that, as mentioned by Cotler and Cuenca (2011) , is characterized by being highly unequal, especially economically and socially, and inefficient in meeting the needs of individuals. This justification is based on an ideological framework of social dominance that promotes, in contexts of inequality, an uncritical and distorted view of the system, as it is useful for maintaining social hierarchies (Gnädinger & Espinosa, 2018; Janos et al., 2018). These findings support the idea that a greater perception of legitimacy is not always positive but can indicate a propensity to justify a system despite the absence of distributive and procedural justice; that is, a failed system (Espinosa et al., 2022a; Janos et al., 2018).

In this regard, Rottenbacher and Schmitz (2012) found that people who tend to justify social inequality are more likely to transgress norms if these hinder the achievement of dominance goals. This could be associated with lower levels of empathy and concern for the well-being of others exhibited by those with higher SDO (Cohrs et al., 2005; Zubieta et al., 2008). Those high in SDO would attach less importance to, for example, vulnerable people falling ill and not being able to access medical care due to the collapse of the health system, as long as they can achieve their goals.

The results of this study show that the higher the perception of legitimacy, the greater the trust in institutions, and this, in turn, has an inverse effect on norm non-compliance. This finding is interesting, as it evidences that the perception of the legitimacy of the system is not limited to the perception of institutional functioning but seems to be elaborated around hegemonic narratives on how the country’s political system should be managed (Vergara, 2018). In this regard, the problems of corruption, economic crisis and the crisis of political representation in Peru have systematically affected perceptions about the country’s political and regulatory systems (Quiroz, 2014). This is due to the predominance of a narrative that prioritizes a neoliberal economic model over a republican system that establishes trustworthy institutions and mediates citizen relationships for their welfare (Vergara, 2018).

Despite the economic growth enabled by the neoliberal model, persistent issues like inequality and institutional failure may eventually impact citizens’ political experiences and shape their daily behaviors (Espinosa et al., 2022a; Vergara, 2018). It should also be noted that, in Peru, different studies show that support for neoliberal economic policies (Rottenbacher & Schmitz, 2012) and higher levels of transgressive behaviors (Janos et al., 2018) are associated with social dominance. This implies a consistency between ideology, perceptions and behaviors such as normative non-compliance.

Building on the previous point, strengthening institutions can foster institutional trust and reduce non-compliance, as people who trust institutions are more likely to agree with authority decisions and comply voluntarily (Murphy, 2004; Tyler, 2001, 2006). Conversely, low trust in institutions leads to greater hopelessness and anomie, which promotes tolerance of and propensity to engage in transgressive practices. This can be seen as a mechanism of adaptation to a system that does not adequately regulate relations between citizens (Beramendi, 2014).

The counterintuitive finding that the perception of legitimacy has a direct relationship with transgression warrants consideration, especially given the finding that trusting in institutions has an inverse relationship. The perception of legitimacy measure denotes the capacity of a system to be rationalized and justified, regardless of its intrinsic goodness or fairness (Beramendi, 2014; Costa-Lopes et al., 2013; Jost et al., 2008). However, it would be erroneous to assert that any system deemed as “legitimate” should be maintained, as the historical trajectory of Latin American democracies has demonstrated. These regimes coexist with significant social and political in- equality, which are, nevertheless, tolerated due to the prevailing beliefs about the workings of democracy in these nations (Imhoff, 2021).

Aside from distorting individuals’ perception of system legitimacy, this study also shows that SDO inhibits the perception of norm transgression in a society in which there are in fact high levels of normative non-compliance (Portocarrero, 2005). This would indicate that, for people who score high in SDO, some behavioral deviations would not pose a problem because “that is how society works”, which is consistent with previous research in which an uncritical view of transgression by those high in SDO is evident (Chaparro, 2018; Espinosa et al., 2022a; Janos et al., 2018). On the other hand, when there is a high perception of transgression, it is observed that self-reporting of transgressive behaviors is reduced in the participants, which is contrary to what was expected at first; namely that the perception of transgression would function as a risk factor for actual norm transgression (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014; Cialdini, 2007). In this regard, these results show that transgression can be problematized in a critical sense. Previous research in several Latin American countries, including Peru, shows a direct link between the perception of corruption -an extreme form of transgression- and the perceived need for systemic change; this is explained by the recognition that corruption undermines societal functioning and stability (Espinosa et al., 2022b).

Additionally, in a context of crisis, “specific” support for institutions can be considered as varying according to the capacity of institutions to meet the demands of citizens in a given period (Price & Romantan, 2004). In this sense, when people believe that the authorities are promoting the welfare and protection of citizens, they evaluate the measures they take positively. On the contrary, if they believe that certain needs are not being met (e.g., economic needs, labor needs, etc.) and that the population is harmed by such measures, the authorities are evaluated negatively. Opinion surveys conducted by the IEP (2020b, 2020d, 2020e, 2020f) showed that, although in the first months of the National Emergency, there was greater approval of the authorities compared to the months prior to the pandemic, this support was not homogeneous across the population. Support was higher among dependent workers of middle and high socioeconomic status, and residents of Lima. On the other hand, independent workers of more vulnerable socioeconomic status, who “feared hunger more than the coronavirus” (Amaya, 2020, p. 79), showed greater disapproval of the policy decisions being made during the emergency because they felt that these did not necessarily protect them (see Beramendi, 2014).

The scenario described is consistent with the findings of the studies by Gätcher and Schulz (2016) and Du et al. (2020) , which show that people tend to develop dishonest behaviors in contexts where there is a negative perception of institutions or where high levels of social inequality persist. In the proposed model, a need-driven transgression indicator emerged, which explains both lower perceived transgression and reduced normative compliance reporting, based on the logic that breaking a rule that offers no protection is not truly transgressive. This supports the third hypothesis of the study, which states that justifications for non-compliance associated with deprivation and need will increase self-reports of transgression.

In the context of the pandemic, it is likely that the critical view of transgression and, consequently, the lesser non-compliance with the rules, is accentuated by the harmful effects of the virus. During the pandemic, these effects were highly salient and there were constant reminders of it by the media as a way of raising awareness. In this sense, non-compliance with the norms would be dangerous if contagion and overloading of the health system are seen as major threats. However, the narrative regarding need invites us to consider the possibility that threats of pandemics are not perceived in the same way by the entire population (Pizarro et al., 2020). This is because, as mentioned, in Peru there is evidence of failures of the socio-political system at the structural and functional level in terms of covering the basic needs of its citizens (Marquina & del Carpio, 2019). As an example, informal work predominates in the country, which represents more than 70 % of the country’s labor force (INEI, 2018). The economic precariousness associated with these conditions places citizens in a situation of vulnerability in the face of crises that may arise (Oxfam Intermón, 2012). Thus, apart from the risk of contagion and the collapse of hospitals, other issues end up being more relevant for certain sectors, such as hunger or unemployment (Amaya, 2020). In sum, this precariousness also acts as a barrier to norm adherence (Beramendi, 2014; Tyler, 2001, 2006).

The pandemic context has additional difficulties for those who suffer from greater deprivation by external circumstances beyond their control. However, this can be extrapolated to any crisis that puts pressure on the satisfaction of people’s basic needs, especially in systems that fail to adequately protect their citizens. In these cases, the cause of transgressive behavior can be attributed to contextual factors (see Delgado, 2013). For example, in Latin American countries, there is a growth in levels of informal commerce in periods of political/economic crises experienced (World Bank, 2021). This can be attributed to the greater scarcity of formal employment in such periods. Thus, people justify their behavior -and that of others facing similar problems- by alluding to situational factors as the cause of their disobedience and suggesting that others in their place would do the same. In this respect, their actions are not to be considered a transgression, but a form of survival. This, in the long run, weakens the system and the institutions.

In sum, it could be said that the transgression of the proposed norms during the National Emergency has its roots in ideological and structural aspects of the system that fail to meet the needs of all citizens. Regarding the ideological aspect, this study highlights how individuals’ SDO can influence non-compliance, while need acts as an inhibitor of compliance. According to the measures of compliance and non-compliance constituted, these findings suggest a spectrum of behavioral justification ranging from an openly selfish position to one of adaptation and subsistence.

While some of the elements which account for pre-COVID transgression also function as predictors in the current scenario, the present study shows that the pandemic (as a major crisis) has modified certain aspects of normative compliance response. Namely, the crisis appears to have ex- acerbated an element of need that reduces compliance. The norms issued during the National Emergency have not affected all sectors equally.

This positions certain groups at higher risk of norm transgression, not because there is no fear of contagion, but because they perceive that there is no other option. If greater compliance with the rules is sought, both in “normal” contexts and in times of crisis (political, economic, health, etc.), it becomes evident that action is needed to reduce the socioeconomic gaps in the population and to promote a system that is more efficient and fairer in the distribution of resources.

It should be noted that the sample was not representative of the social and economic diversity of the country. It is suggested that future studies attempt to incorporate a greater diversity of participants. Such research could be useful to contrast the findings with those found here, specifically considering the element of need and the perception of protection that the norms provide to the citizenry.