Introduction

The study of intestinal function allows to understand growth and maintenance of the digestive tract, as these factors are associated with efficient digestion (Marchini et al., 2011; Marchini, 2005). The absorption of nutrients in the small intestine depends on length, density and placement of intestinal villi, as well as size and density of enterocyte microvilli (Velasco et al., 2010; Roa and Meruane, 2012). Shortening of intestinal villi is associated to pathogens or chemicals that modify the intestinal morphology, which decreases nutrient absorption (Assis et al., 2010).

The study of intestinal villi involves histological procedures, and the first and crucial step is the collection of samples (Sisson and Grossman, 2002). Most tissues are fragile and their morphology may change with excessive manipulation and inadequate sampling techniques. The next and most important step is the fixation of the sampled tissue (Wick, 2008).

Sampling of the intestine is probably the most delicate procedure because of the presence of normal bacteria; therefore, autolysis begins immediately after an animal dies (Sisson and Grossman, 2002), and the ideal sample must come from a recently deceased animal. Usually two or three samples are taken from duodenum, jejunum and ileum (Schweer et al., 2016). In pigs, the recommended sample length is four to five cm (Sisson and Grossman, 2002; Hedemann et al., 2005). To avoid autolysis, it is important to consider that these tissues must be fixed in formalin immediately after sampling (Segalés and Domingo, 2003).

In studies involving intestinal villi, several sampling methodologies have been reported: 1) by cutting the intestine, keeping its content inside and preserving it all in a 10% formalin solution; 2) the pressure technique, by washing the intestine sample in saline solution while pressing it downwards with the thumb and index fingers to empty the content, and further conservation of the sample in a 10% formalin solution; 3) the knotting technique, using nylon suture to knot both ends of the sample, introducing 10% formalin into it and preserving it in the same solution. In other studies, combinations of these techniques have been used (Arce et al., 2008; Itzá-Ortiz et al., 2008; Assis et al., 2010; Velasco et al., 2010).

The aim of the present study was to compare the height, area, and morphological changes caused by washing, pressing and knotting sampling, and conservation techniques of small intestine villi in finishing pigs.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

All procedures involving animals were conducted following guidelines approved in official techniques of animal care and health in México (Ley federal de sanidad animal; articles 19 to 22), NOM-051-ZOO-1995: Humanitarian care of animals during mobilization, and NOM-033-ZOO-1995: Humanitarian slaughter of domestic and wild animals, and the International guiding principles for biomedical research involving animals by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS).

Experimental location and animals

The present study was carried out at Departamento de Ciencias Veterinarias of Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Samples were obtained from 30 Landrace and Yorkshire-crossed finishing pigs, with 74.5 (± 10.8) Kg average body weight. Pigs were slaughtered at the municipal abattoir in Ciudad Juárez (Industrializadora Agropecuaria de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, México) following conventional recommended procedures.

Sampling and evaluation procedures

All samples were taken by the same technician. Individual gastrointestinal tracts were obtained, and samples of each of the three portions of the small intestine were taken by transversally cutting approximately five cm of tubular tissue (Wick, 2008). Samples were taken from the ascending portion of the duodenum, middle portion of jejunum, and ileum portion adjacently prior to the ileocecal valve.

Immediately after evisceration, three samples were taken from the three portions of the intestine and the same amount of different procedures were assigned for each sample: 1) washing the samples: Tissue samples were introduced in a plastic container with % saline solution. Afterwards, samples were held at one end with soft tissue surgical forceps and the intestinal lumen was washed using a 5 mL syringe, removing all contents; 2) applying soft pressure: Samples were placed between the thumb and index finger and a downward soft pressure was applied to eliminate intestinal contents; 3) knotting the samples: Samples were treated by knotting each end with nylon suture, and injecting a 10% formalin solution into the lumen without removing intestinal contents. Immediately after the three procedures, samples were placed in sterile containers with 10% formalin solution for tissue fixation and conservation during 24 to 48 h (Wick, 2008). Afterwards, tissues were processed at the pathology lab at Investigación Aplicada, S. A. de C. V. (IASA) by conventional paraffin embedding, obtaining samples of 4 µm standard thickness, followed by eosin and hematoxylin staining on glass slides for further microscopic morphometric observation and determination of possible morphological changes.

Slides were evaluated using a Leica DM3000 microscope connected to a processor with imaging software (LAS Interactive Measurement ES, LEICA license; Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany). Evaluations were made by measuring 100 intestinal villi per slide, obtaining the average of the following variables:

Villi height (µm), measured from the apex to the base of each villus.

Villus surface area (µm2; Figure 1).

Additionally, cellular desquamation of the villi was classified as mild, moderate or severe, as described by Neog et al. (2011), and cellular autolysis was determined following the description by Jensen et al. (2010).

Statistical analysis

A total of 270 slides were evaluated and randomly distributed in three treatments, according with the procedure (washing, soft pressure, or knotting), as follows: 30 samples per treatment per intestinal portion (270 samples). Villi height and area were analyzed by ANOVA under a completely randomized block design, in which the block factor included the portion of the intestine from which samples were obtained (duodenum, jejunum, or ileum) using proc GLM of SAS program (Version 9.4; SAS Inst. Inc, Cary, NC, USA, 2013).

Figure 1 Schematic representation of measurements of (A) height (µm) and (B) area (µm2) of villi from duodenum, jejunum, and ileum in pigs (adapted and modified from Gartner, 2002).

Results are presented as mean values ± SD. Mean comparisons were performed with Tukey tests and differences in mean value comparisons were considered as statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. Proportions of morphologic alterations related to desquamation and presence of autolysis signs in samples of each treatment were compared using chi- square tests at p<0.05 using the GENMOD procedure of SAS.

Results

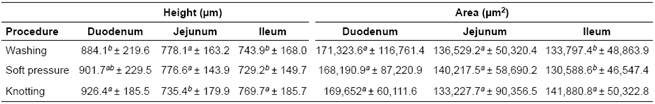

Intestinal villi measurements after sampling procedures are shown in Table 1. Villi height values of knotted samples from duodenum and ileum were higher (p<0.05) compared to the other procedures in the same anatomical portions, which were similar (p>0.05). Also, villi from knotted jejunum samples were the shortest (p<0.05) compared to the other two procedures. Regarding villi area, knotted samples from ileum had higher values compared to the rest of the procedures and intestinal portions (p<0.05).

Table 1 Morphometric characteristics of small intestine villi of pigs subjected to sample procedures of washing, soft pressure, and knotting.

a, b Values with different superscripts indicate significant differences (p<0.05).

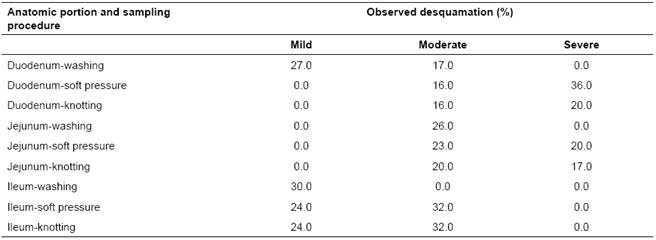

Table 2 Desquamation of small intestine villi in pig samples subjected to washing, soft pressure, and knotting.

Villi desquamation as a result of sampling procedure did not show differences among procedures in the three intestinal portions (p>0.05); however, most samples showed some degree of desquamation (Table 2). In addition, 15 (5.5%) washed, 10 (3.7%) mild-pressed and 14 (5.2%) knotted samples (14.4% overall; p>0.05) showed similar signs of autolysis on the apical portion of the villi.

Discussion

The observation of intestinal villi allows evaluating the factors associated to intestinal structure and functional integrity, including enterocytes and mucosa membranes involved in digestive processes, and is widely used to explain weight gain during pig growth (Marchini, 2005; Skrzypek et al., 2010; Jung and Saif, 2017).

Our results showed differences in height and area of intestinal villi among sampling procedures and should not be considered a response variable of an experimental factor. Regarding the height observed in knotted samples, it has been reported that repair mechanisms after a lesion involving epithelial integrity may be involved in intestinal segments with shorter, thinner and fewer villi. These findings related to villi morphometry are associated to digestive disorders caused mainly by bacteria (Escherichia coli) or parasites (Eimeria spp and nematodes) that can activate humoral or cellular immune mechanisms and may cause changes in villi structure (length or area) and mature enterocytes numbers (Gartner, 2002). These mechanisms tend to reintegrate the epithelial tissue slowly and progressively. On the other hand, villus size and the relationship between villi number and epithelial area tends to diminish as age increases (Tsukahara et al., 2012), which may be the case of the present study, as animals may have gone thru different intestinal tissue repair procedures before the experiment. The knotting procedure is thought to be less “aggressive” to the intestinal villi, as it consists of knotting both ends of the intestine and introducing formalin solution, without any additional manipulation that could deteriorate the tissue. The washing and pressing procedures involve mechanical manipulation as the pressure wash or the sweep made with the fingers, which may have affected the tissue structure, possibly explaining the lower height of villi in washed and softly-pressured samples. Villi height and area were higher and wider in the duodenum, and tended to decrease towards the caudal portions of the intestine. Other authors reported variations in villi length among species and gastrointestinal physiology; in particular, villi in the cranial portions of the intestine are larger, more uniform and have a larger area, which optimizes digestion and absorption processes (Tsukahara et al., 2012). In swine, villi height increases notably since the first day of life (Huygelen et al., 2014) as their area increases gradually with age (Arce et al., 2008; Yunusova et al., 2013; Horn et al., 2014). Alterations in intestinal villi due to histologic cutting procedures have been reported, which is known as histologic artifacts. These artifacts represent unwanted changes that may occur during the cutting and mounting of a sample on a glass slide or may be due to inadequate sample processing (Narváez, 2015).

It is worth mentioning that the tissue cutting method used during the sample mounting process in the present study had an adequate quality control, thus minimizing potential artifact effects and other alterations. Therefore, the morphologic alterations observed are considered to be randomly-occurring in the three experimental procedures. Other authors (Bravo, 2011; Venne et al., 2014) have pointed out that some histologic artifacts may induce changes such as autolysis on cells and tissues by using an inadequate fixation technique, prolonged time of fixation, the use of extremely small amounts of the fixing agent -such as 10% solution of formalin, incomplete inclusion of the tissue, use of poorly sharpened blades, incorrect placing of the blade, presence of paraffin residues, folding of the tissue, poor elimination of stains used, presence of air bubbles, among others. Wick (2008) and Bravo (2011) recommend appropriate identification of the predictable changes in the sample due to improper processing or handling. On the other hand, Narváez (2015) points out that these artifacts may be effectively identified and have no influence on the study.

Autolysis or post-mortem degeneration observed in some samples of the present study may be due to improper fixation. According to Rubio et al., (2010) and Bravo (2011), when the tissue is not fixed rapidly or when the volume of fixative compound is not sufficient for the size of the sample, autolysis may begin, with the subsequent loss of observable detail and morphology of cells. Nevertheless, these can be considered permissible changes in a study that involves intestinal villi and are easily identified with common microscopic observation (Bravo, 2011). It is important to mention that, even though these changes occurred in similar proportions in all three sampling procedures, the knotting procedure showed to be less “aggressive” to the villi. Also, this technique may take longer to carry out since it requires other person to help with the knotting and injection of formalin solution. In conclusion, although none of the procedures in the present study can be considered better, the knotting procedure is recommended when intestinal cell morphometry -especially villi height and area - is to be evaluated. Additionally, artifacts can be found indistinctly in the washing, pressing and knotting procedures, and they may be related with epithelial restoration processes.