Introduction

The subclass Copepoda includes small crustaceans inhabiting almost every aquatic biotope, as well as semiterrestrial habitats such as mosses and humid forest soils. Copepods inhabit from deep-sea trenches up to high mountain lakes of the Andes, Mount Kenya and the Himalaya. The total number of copepods exceeds 11,300 accepted species and subspecies; together with nematodes they are the most abundant metazoans on Earth (Walter & Boxshall, 2019). In continental waters, about 2500 species and subspecies are known, but this number increases when coastal lagoons with different salinity values are also considered. The body size of adult copepods ranges from 0.2 to 17 mm, but most average 1-2 mm. Copepods can be free-living, symbiotic as well as internal or external parasites of almost all major aquatic metazoans (Huys & Boxshall, 1991). In freshwaters, parasitic copepods are found only in fish.

A checklist of the free-living copepods of continental waters of Colombia was published 12 years ago (Gaviria & Aranguren, 2007), including 69 species and subspecies (14 Calanoida, 41 Cyclopoida, 14 Harpacticoida).

During the past years, the copepod fauna of new biotopes such as coastal lagoons, phytotelmata of the rain forest, Amazon floodplain lakes (varzea and igapó), freshwater lagoons (ciénagas), wetlands of the eastern Llanos, Andean lakes, ponds, wet mosses and reservoirs have been studied. Moreover, the results presented here include reports of parasitic copepods of fish (Lernaeidae and Ergasilidae) obtained from studies developed in the departments of Valle del Cauca, Meta and Magdalena.

Coastal lagoons were considered in our inventory due to their topotypical character with narrow connection to the sea. Because of their connection to the marine environment, they show a wide range of salinity. Estuaries like those from the Pacific coast are not considered in the inventory. Coastal ponds are morphologically isolated from the sea and can temporarily reach hypersalinity. Thus, the following groups with brackish or marine representatives are considered in the inventory: Calanoida (Acartiidae, Lucicutidae, Pseudodiaptomidae, Temoridae), Cyclopoida (Halicyclopinae, Kelleridae, Oithonidae, Apocyclops) and Harpacticoida (Ameiridae, Ectinosomatidae, Laophontidae, Metidae, Miraciidae, Tachididae, Tegastidae, Cletocamptus, Mesochra). The remaining groups considered are the following: Calanoida (Centropagidae, Diaptomidae), Cyclopoida (Cyclopinae, Eucyclopinae) and Harpacticoida (Canthocamptidae, Parastenocarididae).

Aims of this contribution are to elaborate a revision of the species richness of continental copepods of Colombia, compare their diversity in relation to the previous inventory (Gaviria & Aranguren, 2007), indicate orders, families, genera and species represented in the country, list the records of the copepod species in the different departments and biotopes, compare the species richness of the Colombian genera in relation to the Neotropical Region, and indicate the world distribution of the Colombian species. Finally, we propose points of future research in order to fill the gaps of the knowledge of diversity of the continental copepods of Colombia.

Materials and methods

The list of species presented here is the result of a critical compilation of published and unpublished records that appeared after 2007, and of personal observations of the authors and colleagues. Unpublished records are those indicated in Aranguren (2014) and obtained from the study of zooplankton of Amazonian lakes (varzea type: Yahuarcaca, Tarapoto and El Correo; igapó type: Zacambú), Andean lakes (Tota, Fúquene, Iguaque and Guatavita) and Caribbean ciénagas (Ayapel, Momil, Purísima and Vipis). Part of this information was published in Aranguren et al. (2011).

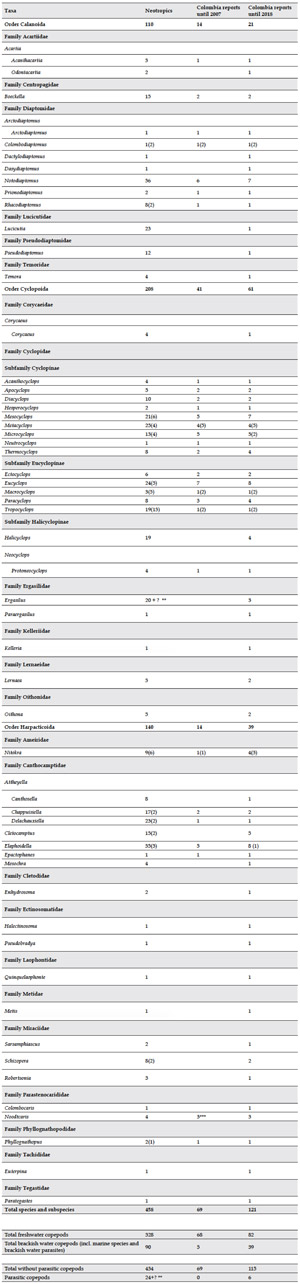

A synopsis of the families, genera, species and subspecies listed for the country until 2007 and until 2018 is shown in Table 2. For comparative purposes, the corresponding number of species and subspecies per genus occurring in the Neotropical region is included.

The published references include species of free-living and parasitic copepods from continental biotopes and coastal lagoons and ponds, recorded during different types of studies, as follows:

-

Zooplankton during limnological studies of Amazonian lakes (Aranguren-Riaño et al., 2011), wetlands of the Orinoco basin (five lakes near the Orinoco River) (Rivera-Rondón et al., 2010), Andean lakes (Aranguren-Riaño et al., 2011) and reservoirs (Villabona-González et al., 2007, 2015; Aranguren-Riaño & Monroy-González, 2014) and Caribbean ciénagas (Gallo-Sánchez et al., 2009; Álvarez, 2010; Aranguren-Riaño et al. 2011; Villabona et al., 2011; Jaramillo-Londoño & Aguirre-Ramírez, 2012).

Benthic harpacticoids collected in phytotelmata of the rain forest during taxonomic studies (Gaviria & Defaye, 2012), and in an Andean lake and a pond of the páramo region during taxonomic and phylogenetic studies (Laguna de Buitrago, Chingaza; pond near Laguna de San Rafael, Puracé) (Gaviria & Defaye, 2012, 2015, 2017a, 2017b).

Limnetic and benthic species from coastal lagoons and temporary ponds of the Caribbean region during studies of taxonomy and biodiversity: the investigated coastal lagoons were Laguna del Navío Quebrado (La Guajira) (Fuentes-Reinés & Gómez, 2014; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2014a, 2014b, 2015; Suárez-Morales & Fuentes-Reinés, 2014, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c) and Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Magdalena) (Fuentes Reinés et al.,2013; Fuentes-Reinés & Zoppi de Roa, 2013a, 2013b; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2018; Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2018). The temporary ponds located in the Magdalena department are located in Pozos Colorados (Gómez et al., 2017) and Puebloviejo (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2015).

Parasitic copepods and their fish hosts from various rivers and a coastal lagoon, studied by Cressey & Colette (1970) (mouth of Dagua River, Valle del Cauca), Thatcher (1984) (Pital River, Valle del Cauca), Thatcher (2000) (Meta River, Meta), Fuentes-Reinés et al. (2012) (southern Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Magdalena), Sarmiento & Rodríguez (2013) and Muriel-Hoyos et al. (2015) (Vichada River, Meta).

New records of species for Colombia as well as new records of already known species are listed, indicating their overall distribution, their presence in the different Colombian departments and habitats, and the corresponding bibliographic references.

The records of personal observations (SG – S. Gaviria; NA – N. Aranguren; JM – J. Molina; DD – D. Defaye, DB – D. Baribwegure) are based on samples obtained at the following localities and years:

-

Amazonas: Laguna de Tarapacá, near Rio Putumayo, SG (2001). Laguna de Yahuarcaca, Laguna Zacambú, Laguna El Correo and Laguna Tarapoto, NA (2007).

Antioquia: Microestación, Campus Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, SG (1999). Reservoir La Fé, SG (1999); Reservoir Porce II, SG (1999); Reservoir Riogrande II, SG (2001); lake at fishfarm Gaiteros, Sopetrán, SG (2001); Lake “Dos Lagos”, Carmen de Viboral, SG (2001); Lake Cerro del Padre Amaya, Palmitas, SG (2001); Lake Piedras Blancas, Guarne, SG (1999); Ciénaga Vallecitos, Caucasia, SG (1999).

Boyacá: Laguna de Iguaque, SG (2010); wet moss páramo de Cómbita, SG & DD (2016); Laguna Verde, páramo de Pisba, NA & JM, 2018; Laguna de Socha, Laguna Peña Negra and Laguna Los Fríos NA (2016).

Cesar: Ciénaga de Zapatosa, SG & DB (1999).

Chocó: Ciénaga de Tumaradó and Ciénaga de Perancho, SG (2000).

Córdoba: Ciénaga de Ayapel, SG 1999; Ciénaga de Betancí, SG 2002; Ciénaga de Lorica, SG (2002).

Cundinamarca: Fishpond in La Mesa, NA (1994).

Magdalena: Ciénaga de Pijiño, SG (1999).

Meta: Laguna Mateyuca, Puerto López, SG (1999).

Tolima: Ciénaga de Guarinocito, NA (2007).

Information about the overall distribution of the freshwater species was extracted from Dussart & Defaye (2002, 2006), Defaye & Dussart (2011), Fuentes-Reinés et al. (2013) and Perbiche-Neves et al. (2014). The distribution of planktonic species from brackish water follows Razouls et al. (2005-2018) and of benthic species of brackish water according to Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales (2013, 2015, 2018), Fuentes-Reinés & Gómez (2014), Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales (2014a, 2014b), Fuentes-Reinés et al. (2013b, 2015, 2018) and Gómez et al. (2017). Taxonomy follows Walter & Boxshall (2019) (http://www.marinespecies.org/copepoda).

Results

The taxonomic list (Table 1) presents the new records of copepods in continental waterbodies, including 15 families, 25 genera and 52 species and subspecies not recorded in a previous Colombian inventory. The current number of copepods recorded in Colombia comprises 121 taxa (21 calanoids, 61 cyclopoids and 39 harpacticoids), including taxa from coastal lagoons and ponds, as well as parasitic species.

Besides the new records for the country, we report the occurrence of 39 species in new departments, 43 new habitat records and seven new bibliographic references (Table 1). Eight of the 32 Colombian departments, i.e. Arauca, Caldas, Caquetá, Casanare, Guaviare, Putumayo, Quindío and Vaupés, lack reports of copepods. Most records are from Magdalena (42), La Guajira (34) and Cundinamarca (27).

Seventy-four percent of the species are distributed in lowland waterbodies, 17 % in highland regions (from 2000 m a. s. l.) and 9 % in both regions. Finally, the known altitudinal or geographic range of distribution of 29 species has increased.

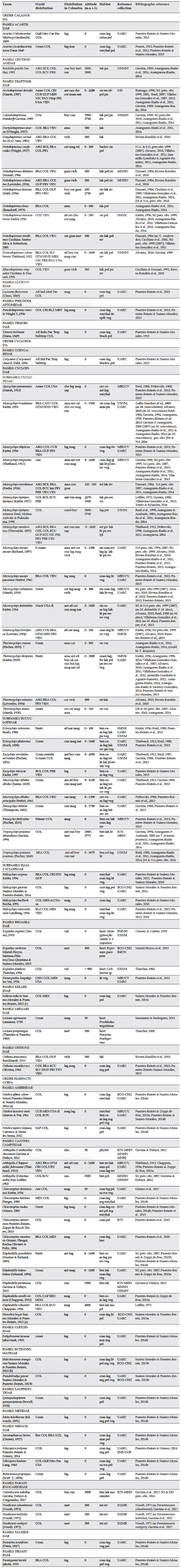

Table 1. Taxonomic list of the species and subspecies of copepods reported after 2007 in continental waterbodies, semiterrestrial biotopes, coastal lagoons and temporal offshore ponds of Colombia. Taxa known before 2007 but with expanded distribution in new departments, increase of altitude range and habitats not indicated before, are included. Expansion of altitudinal range, departments and habitats are indicated in bold.

Abbreviations: World distribution: Amer – America, Ant – Antilles, ARG – Argentina, Atl – Atlantic Ocean, BLZ – Belize, BOL – Bolivia, BRA – Brazil, CAN – Canada, CAR – Caribbean Sea, CAF – Central African Republic, CHL – Chile, CHN – China, COL – Colombia, Cosm – cosmopolitan, CRI – Costa Rica, CUB – Cuba, ECU Ecuador, SLV – El Salvador, Eur – Europe, GUF – French Guyana, GTM – Guatemala, Gulf-Mex – Gulf of Mexico, HTI – Haiti, Hisp – Hispaniola, HND – Honduras, Ind – Indian Ocean, Indo-Pac – Indo-Pacific Ocean, REU – La Réunion, Les-Ant – Lesser Antilles, MDG – Madagascar, MEX – Mexico, MEX-si – Mexico (Sinaloa), Med – Mediterranean Sea, Neotr – Neotropical region, NIC – Nicaragua, NZL – New Zealand, PRY – Paraguay, Pac – Pacific Ocean, Palearc – Palearctic region, Pantr – pantropical, PER – Peru, PAN – Panama, PRI – Puerto Rico, ROU – Romania, S-Amer – South America, SAF – South Africa, Subtrop – subtropical, TTO – Trinidad and Tobago, Trop – tropical, URY – Uruguay, USA – United States of America, USA-ca – United States of America (California), USA-fl – United States of America (Florida), VEN – Venezuela. Distribution in Colombia (Departments): ama (Amazonas), ant (Antioquia), atl (Atlántico), boy (Boyacá), cal (Caldas), cau (Cauca), cho (Chocó), cor (Córdoba), cund (Cundinamarca), guai (Guainía), hui (Huila), lag (La Guajira), ces (Cesar), mag (Magdalena), met (Meta), nar (Nariño), nsan (Norte de Santander), san (Santander), tol (Tolima), val (Valle del Cauca), vich (Vichada). Habitat in Colombia: coast-lag – coastal lagoon, backw – backwater of a river, ben – benthos, cav – cave, cie – “ciénaga” (=freshwater lagoon), coas-lag - coastal lagoon, coas-lag-fw – coastal lagoon/freshwater zone, coas-pd – coastal pond, de – demersal, epib – epibenthic, est – “estero” (typical meadow in the east plains “Llanos”), estua – estuary, euryhal – euryhaline, ig – “igapó” lake, int-riv – interstitial of a river, lak – lake, lit – littoral, mg – mangrove, mar – marine, mm-pd – man-made pond, mo – moss, pel - pelagic, phytot – phytotelmata, pl – plankton, pn – pond, res – reservoir, sa-wa – saltwater, semiter – semiterrestrial, sw – swamp, tan – water tank, tpl – treatment plant, var –“ varzea” lake, veg – macrophytes. Acronyms: DZMB – Deutsches Zentrum für Marine Biodiversitätsforschung, Senckenberg am Meer, Wilhemshaven, Germany; ECO-CHZ – Collection of Zooplankton at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Chetumal, Mexico; EMUCOP – Copepoda collection of the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Mazatlán Marine Station, Sinaloa, Mexico; FMNH – Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Ill., USA; ICN-MHN – CR – Museo de Historia Natural – Crustacean Colección – Instituto de Ciencias Naturales at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia; IMCN – Zoological Collection of Scientific References, Departmental Museum of Natural Sciences Federico Carlos Lehmann Valencia, Cali, Colombia; INV Museum Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas INVEMAR, Santa Marta, Colombia; MBUCV – Museo de Biología de la Universidad Central de Venezuela, Crustacean Section, Caracas, Venezuela; MNHN-Muséum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France; MNRJ – Museo Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; NHMW – Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria; UARC – Museo de Colecciones Biológicas at the Universidad del Atlántico, Barranquilla, Colombia; UIS – Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colección Limnológica; USNM – U.S. National Museum, Washington, USA. Bibliographic reference: pers. obs. – personal observation, DB – D. Baribwegure, DD – D. Defaye, JM – J. Molano, NA – N. Aranguren, SG – S. Gaviria.

In the Neotropical region as a whole, the number of copepods living in inland waters comprises 458 species and subspecies. That value is nearly four times as high as that in Colombia (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparative taxonomic synopsis of the families, genera and subgenera of the copepods reported in continental water bodies of Colombia until 2007 (Gaviria & Aranguren, 2007) and until 2018 (present inventory), and their representation in the Neotropical region. Numbers indicates species for each genus (numbers of subspecies are indicated in brackets). Numbers in bold indicate total number of species and subspecies for each order. * Parasitic genera, **Ergasilus comprises 20 species in South America and Mexico, and an unknown (?) number of species in Central America and the Antillean Islands. *** Species of Parastenocaris (2007) were allocated to the new genus Noodtcaris.

Discussion

The increase in copepod diversity presented here for Colombia reflects the exploration of new territories and new biotopes as well as taxonomic changes in the subclass Copepoda during the past 11 years. Thirteen species new to science have been described from Colombia since 2007.

The number of brackish taxa (including marine species collected in brackish environments) found in coastal lagoons and temporal ponds near the coast, reached 39 species and subspecies. The number of copepods parasitic on fish has risen to six species. This number is expected to increase when the Amazonian region is surveyed; it has not yet been studied for ergasilids and lernaeids.

Calanoid copepod numbers have been enriched by the discovery of the family Pseudodiaptomidae (Pseudodiaptomus marshi) and one additional species of Acartiidae (Acartia (Odontacartia) lilljeborgi) in coastal lagoons. Two additional families, Lucicutidae (Lucicutia flavicornis) and Temoridae (Temora turbinata), typical of marine waters, were also found in these environments. L. flavicornis is an oceanic species that sometimes invades neritic water (Vives & Shmeleva, 2006). A coastal lagoon is not a typical habitat for that species and the two specimens found in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013) possibly arrived there with tidal currents. The same holds true for the presence of T. turbinata in the coastal lagoon Navío Quebrado (Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2015) because the species is a typical neritic-oceanic species (Vives & Shmeleva, 2006).

In freshwaters, three additional species of the family Diaptomidae were recorded, two in the Amazon (Dactylodiaptomus pearsei and Notodiaptomus linus) (Aranguren, 2014) and one in the Orinoco basin (Dasydiaptomus coronatus) (Rivera-Rondón et al., 2010). Within calanoids, Notodiaptomus is the genus with the highest species number in Colombia (7), and is also the genus with the highest species richness in South America (Perbiche-Neves et al., 2014). The distribution of two species of the genus, Notodiaptomus dilatatus and N. echinatus, expanded to the Vichada department in the Orinoco basin (Rivera-Rondón et al., 2010). Additionally, Notodiaptomus simillimus and N. coniferoides increased their distribution to Córdoba in the Caribbean region (Villabona-González et al., 2011. Jaramillo-Londoño & Aguirre-Ramírez, 2012; Aranguren, 2014).

Notodiaptomus henseni was newly registered in Córdoba and Boyacá. In Boyacá, the species was found in a high mountain lake (Laguna Verde, Páramo de Pisba, 2740 m a. s. l.) (Aranguren & Molano, pers. obs. 2014). This represents the second record of a species of Notodiaptomus in mountain waterbodies of the Andes. Recently, Alonso et al. (2017) described Notodiaptomus cannarensis from a water reservoir in southern Ecuador, located at 2127 m a. s. l.

Notodiaptomus coniferoides has a wide distribution in South America, ranging from the Amazon River to the mouth of the Paraná River (Perbiche-Neves et al., 2013; Previatelli et al., 2013). In Colombia it has been recorded at the interandean Magdalena valley and in the Caribbean region (Gaviria & Aranguren, 2007). Specimens from Venezuela identified by Dussart (1984) as N. coniferoides should be referred to N. simillimus, a species very similar to the former (Cicchino et al., 2001). It is possible that some Colombian records of N. coniferoides correspond to N. simillimus, as is apparently also the case in northern Brazil (Previatelli et al., 2013).

Notodiaptomus maracaibensis is the species of the genus with the widest distribution in the Colombian Caribbean region. It was found together with three other species of the genus (Notodiaptomus henseni, N. coniferoides, N. simillimus) in the Ciénaga de Ayapel, Córdoba, where it reached the highest abundances among the planktonic copepods (Villabona-González et al., 2011). High densities of N. maracaibensis were also observed in the ciénaga-complex of Malambo, near the Magdalena River (Atencio et al., 2005). In the Lago de Maracaibo, Venezuela (locus typicus of the species), its populations are thought to be threatened. Due to its distribution and populations size in Colombia, its vulnerable status at the IUCN Red List (Baillie & Groombridge, 1996) should be re-evaluated (Reid, pers. com. to SG).

Four species of Diaptomidae, Rhacodiaptomus ringueleti, Notodiaptomus dilatatus, Notodiaptomus linus and Notodiaptomus echinatus, seem to be restricted to lakes and rivers east of the Cordillera (Dussart, 1984; Cicchino & Dussart, 1991; Rivera-Rondón, 2010; Aranguren, 2014), whereas records of N. simillimus stem from the same region and also from the Caribbean plains (Cicchino et al, 2001; SG, pers. obs. 2007; Villabona-González et al., 2011).

Arctodiaptomus dorsalis is also widely distributed in Colombia, newly registered in Córdoba (Aranguren, 2014) as well as in Santander (Reid, 2007) and Norte de Santander in the Andean Cordillera (Villabona-González et al., 2007). This species has an apparent center of origin in the lowlands around the Gulf of Mexico, Central America, the Greater Antilles and northern South America (Reid, 2007). The latter author discussed the increase of the species’ distribution further north in the United States and further south in Colombia, influenced by human activities such as aquaculture and by colonisation of suitable eutrophic waterbodies. New records in the Caribbean region (Ciénaga de Ayapel) (Aranguren, 2014) and an Andean reservoir (Laguna Acuarela, Norte de Santander) (Villabona-González et al., 2007) in Colombia point to an expansion trend to the south.

Prionodiaptomus colombiensis is also widely distributed and was recorded for the first time in Córdoba (Álvarez, 2010) in the Caribbean region. Together with N. henseni, it is the only diaptomid copepod distributed from lowland waterbodies up to Andean lakes with an altitude of 2600-2800 m a. s. l.

Colombodiaptomus brandorffi, formely known from the paramo lakes of Cundinamarca, was also recorded from Laguna de Iguaque in Boyacá (SG pers. obs. 2010; Aranguren, 2014). No additional records of the cold stenothermic centropagids (Boeckella) were registered.

With 20 new taxa recorded in Colombia, the order Cyclopoida now reaches 61 species and subspecies. Two families, i.e. Kelleridae and Ergasilidae, formerly belonging to the order Poecilostomatoida, are now allocated in the order Cyclopoida. Khodami et al. (2017) recently demonstrated that the poecilostomatoid lineage lies within the latter order. Thus, Kelleria reducta and four ergasilid species were added to the list of cyclopoids.

Other nomenclatural changes have occurred in this order. Mesocyclops venezolanus Dussart, 1984 is no longer accepted and is now recognised as a junior synonym of Mesocyclops brasilianus Kiefer, 1933, according to Gutiérrez-Aguirre et al. (2006). The cyclopoid copepod Microcyclops alius (Kiefer, 1935) is a junior synonym of Microcyclops dubitabilis Kiefer, 1934 (Gutiérrez-Aguirre & Cervantes-Martínez, 2016).

The exploration of coastal lagoons has also contributed to the increase in the species number of other cyclopoids for the country. Various brackish-water species now form part of the inventory. The genus Halicyclops, with four species (H. exiguus, H. gaviriai, H. hurlberti, H. venezuelaensis), was found in the plankton of brackish environments (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013; Suárez-Morales & Fuentes-Reinés, 2014; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2015, 2018). Another new family, Oithonidae, contributed with one new species (Oithona oswaldocruzi) collected in coastal lagoons (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2015). The species O. amazonica was found in freshwaters of the Orinoco basin (Rivera-Rondón, 2010). Corycaeus clausi (family Corycaeidae) was registered for the first time in a coastal lagoon in La Guajira department (Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2015).

Some typical freshwater species were recorded in coastal lagoons. They were apparently collected in the freshwater areas of the lagoons and constitute new species for Colombia: Eucyclops titicacae and Paracylops fimbriatus (Eucyclopinae), as well as Mesocyclops ellipticus and Microcyclops anceps pauxensis (Cyclopinae) (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2013, 2015). Other freshwater species, i.e. Ectocyclops rubescens, E. phaleratus, Macrocyclops albidus albidus, M. albidus principalis and Paracyclops chiltoni (found in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta), are new for the department of Magdalena (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013).

The Cyclopinae Thermocyclops minutus, registered in Caribbean and Orinoco waterbodies (Alvarez, 2010; Rivera-Rondón et al., 2010), as well as Thermocyclops crassus from Caribbean and Amazonean lakes (Aranguren, 2014), are also new for the country. Collado et al. (1984) and Reid (1989) mentioned that most published records of T. crassus in South and Central America and the Caribbean region should be referred to T. decipiens, and that the only confirmed record of T. crassus is from Costa Rica. T. crassus has a cosmopolitan distribution outside the Neotropical region. Therefore, new records of T. crassus in Colombia should be accepted with caution. The species Thermocyclops tenuis extended its distribution to the departments Córdoba and Magdalena in the Caribbean region. Thermocyclops decipiens, with records in four new departments, is now present in 13 departments of Colombia. It is probably the most common Thermocyclops species in the country, as it was also mentioned for the neotropics (Reid, 1989). The subspecies Tropocyclops prasinus prasinus and T. prasinus altoandinus were found for the first time in the department of Boyacá (Aranguren, 2014; NA & JM pers. obs. 2018).

Eucyclops serrulatus has been recorded from several localities of Colombia. Nevertheless, and according with Alekseev et al. (2006), E. serrulatus is a Palearctic species. Records in America may be from introduced populations or even represent as yet undescribed species (Mercado-Salas et al., 2012). The redescription of E. serrulatus and other six species included characters not considered in the past that helped to discriminate the species: pore signature of the cuticula, ornamentation of the antennal basis and of the intercoxal sclerite of the fourth pair of legs (Alekseev et al., 2006). In a study of Eucyclops-species from Mexico, Mercado-Salas & Suárez-Morales (2014) redescribed four of them and considered that most of the remaining species of the genus in the Neotropical region should be redescribed. Eight species of the genus are now known from Colombia, but that number is probably an understimation.

As parasitic copepods are now also considered in the inventory, we have listed six species belonging to the cyclopoid family Ergasilidae (4) and Lernaeidae (2). Two ergasilids have been found in fish inhabiting rivers in southwestern Colombia (Ergasilus argulus and E. pitalicus), one in the Eastern Plains in the Meta departement (E. curticrus) and one in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Paraergasilus longidigitus). The family Lernaeidae is represented by Lernaea pirapitingae from fish of the Meta River (Thatcher, 2000) and by Lernaea cyprinacea. The latter species was introduced to Colombia with fish (Carassius auratus and Cyprinus carpio) used in aquaculture, and it has been also recorded in Trichogaster microlepis (Rodríguez Gómez, 1981). Alvarado-Forero & Gutiérrez-Bonilla (2002) argued that this parasitic copepod is widespread in the country. It was also found recently as parasite of Prochilodus magdalenae from a fish farm in Gaira, department of Magdalena (Sarmiento & Rodríguez, 2013). In Mexico, three species of ergasilids and L. cyprinacea have been reported in freshwater fish (Morales-Serna et al., 2012). Most of the parasitic copepods in South America have been recorded from the Amazon and the northeastern region of Brazil. In the Brazilian Amazon, 14 species of Ergasilus and 2 members of Lernaea have been recorded (Muriel-Hoyos et al., 2015; Luque & Tavarés, 2007). This means that at least ergasilids can be expected also as fish ectoparasites in the Colombian Amazon.

The order Harpacticoida showed the highest increase in species richness (2007: 14, 2018: 39). Within the 25 new species recorded for the country, 10 are new to science. Newly described species with the locus typicus in Colombia were Nitokra affinis colombiensis (Ameiridae), Attheyella (Canthosella) chocoensis, Cletocamptus nudus, Cletocamptus samariensis, Elaphoidella paramuna, Mesochra huysi (Canthocamptidae), Halectinosoma arangureni, Pseudobradya gascae (Ectinosomatidae), Schizopera evelynae (Miraciidae), and Colombocaris isabellae (Parastenocarididae).

The intensive taxonomic research on harpacticoids from the coastal lagoons Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2013; Fuentes-Reinés & Zoppi de Roa, 2013a, 2013b; Suárez-Morales & Fuentes-Reinés, 2015a; Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2018) and Laguna Navio Quebrado (Fuentes-Reinés & Gómez, 2014; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2014a, 2014b; Suárez.Morales & Fuentes-Reinés, 2015b), from two temporal ponds in the Caribbean region (Fuentes-Reinés et al., 2015; Gómez & Fuentes-Reinés, 2017), from water bodies in the páramo (Gaviria & Defaye, 2012, Gaviria et al., 2017a, 2017b), and phytotelmata from the rain forest (Gaviria & Defaye, 2012) explains this increase in species numbers.

Most harpacticoid copepods are typical inhabitants of benthic environments. The benthic families recorded in Colombia are Ameiridae, Canthocamptidae, Cletodidae, Ectinosomatidae Laophontidae, Metidae, Parastenocarididae, Tachididae and Tegastridae. Few families of the order have worldwide representatives in the plankton of coastal lagoons. In Colombia, only the family Miraciidae is known in this environment, represented by Schizopera (two species), Sarsamphiascus and Robertsonia (each with one species).

A revision of the columbiensis-group of Noodt (1972) from the family Parastenocarididae led Gaviria et al. (2017a, 2017b) to propose a new genus (Noodtcaris) for Parastenocaris columbiensis, Parastenocaris kubitzkii and Parastenocaris roettgeri together with a Brazilian species. As no other species of Parastenocaris has been recorded in Colombia, the genus is no longer part of the Colombian copepod fauna.

Three freshwater canthocamptid copepods (Elaphoidella bidens bidens, Elaphoidella grandidieri, Atheyella (Chappuisiella) fuhrmani) already known from Colombia were recorded from coastal lagoons (Fuentes-Reinés & Zoppi de Roa, 2013a, 2013b; Fuentes-Reinés & Suárez-Morales, 2014b), probably collected in their freshwater zone. The species Attheyella (Chappuisiella) pichilafquensis Löffler, 1962, also registered in Colombia, is considered by some authors (Löffler, 1962, 1963; Gaviria & Aranguren, 2007) to be an independant species, and by others (Reid, pers. com. to SG) a synonym of A.(Ch.) fuhrmanni (Thiébaud, 1912). This calls for re-studying the comparative morphology of both species. Elaphoidella schubarti was recorded by Löffler (1972) in Colombia, collected in high mountain waterbodies of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

The significant proportion of copepod species recorded in lowland waterbodies (74 %) compared within highland regions (17 %) indicates a high heterogeneity of ecological conditions in this area. Nine percent of the species are distributed in both regions.

Concerning the presence of copepods in the Colombian departments, 8 of the 32 departments (Arauca, Caldas, Caquetá, Casanare, Guaviare, Putumayo, Quindío and Vaupés), have no reports. Except Caldas and Quindío, the remaining departments are located in the Orinoco and Amazonas basins, where few surveys of aquatic invertebrates have been carried out. The departements with the highest number of records are Magdalena (42), La Guajira (34) and Cundinamarca (27), due to the expert taxonomists that have worked in these regions.

The diversity of copepods in Colombian continental waters, including brackish species of coastal lagoons and ponds is with 119 species, lower than in Mexico (159 species) (Suárez-Morales et al., 1998). Considering only freshwater taxa (82 species and subspecies), the diversity of copepods in Colombia is lower than in Brazil (200) (Reid, 1998; Rocha & Botelho, 1998; Santos Silva, 1998; Previatelli & Santos-Silva, 2007; Perbiche-Neves et al., 2013; Silva & Perbiche-Neves, 2016; Corgosinho et al., 2017), similar to Mexico (78) (Suárez-Morales et al., 2000) and higher than in Venezuela (66) (Dussart, 1984), Cuba (56) (Collado et al., 1984) and Costa Rica (25) (Morales-Ramírez et al., 2014).

Conclusions

The list presented here contributes to a better understanding of the biodiversity of Copepoda in Colombia. As only two coastal lagoons and two coastal ponds in the Caribbean region were investigated, surveys in other brackish environments are expected to increase our knowledge about copepod diversity. Ground water environments, including the interstitial of rivers and lakes, continue to be virtually unstudied habitats for copepods. Species of parastenocaridids, canthocamptids, certain ameirids and cyclopoids should occur there. The further study of unexplored territories and poorly studied habitats like benthos of water bodies, ground waters and semiterrestrial biotopes should increase the number of copepods of the continental waters of Colombia.