Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Científica General José María Córdova

versão impressa ISSN 1900-6586versão On-line ISSN 2500-7645

Rev. Cient. Gen. José María Córdova vol.17 no.25 Bogotá jan./mar. 2019 Epub 05-Nov-2019

https://doi.org/10.21830/19006586.138

Justice and Human Rights

Citizen perception of human rights: the case of Monterrey, Nuevo León

* Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, México. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2496-1853 ricardo.gutierrezfe@uanl.edu.mx Universidad

** Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, México. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0907-452X xochitl.arangomr@uanl.edu.mx Universidad

The violation of human rights abnegates the exercise of a person or group's freedoms and opportunities. These violations can be perpetrated by any actor in society, as well as by the government itself. In Mexico, mainly in the northern states, discrimination is noticeably apparent, whether originated by social status or sexual preferences, generating a grievous violation of the right to equality. This article presents a brief overview of the evolution of human rights in the world, their definitions and characteristics, as well as their application and importance in Mexican legislation. In parallel, it analyzes the citizens of Monterrey's perception of human rights, using the case study completed by the Faculty of Political Science and International Relations of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León as a reference.

KEYWORDS: citizen perception; discrimination; government; human rights; society

La violación de los derechos humanos niega el ejercicio de libertades y oportunidades adquiridas por una persona o grupo. Dichas violaciones pueden ser cometidas por todos los actores de la sociedad y por el gobierno mismo. En México, principalmente en los estados del norte, la discriminación es uno de los casos más evidentes, ya sea por la condición social o las preferencias sexuales, lo que genera una grave violación al derecho a la igualdad. Este artículo presenta un breve panorama de la evolución histórica de los derechos humanos en el mundo, sus definiciones y características, así como su aplicación e importancia en la legislación mexicana. A la vez, se analiza la percepción de los ciudadanos de Monterrey en materia de derechos humanos, para lo cual se toma como referencia el estudio de caso realizado por la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Relaciones Internacionales de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

PALABRAS CLAVE: derechos humanos; discriminación; gobierno; percepción ciudadana; sociedad

Introduction

The history of humanity has been marked, over the years, by horrific events that have forced society to reconsider and restructure the path of a civilized and organized society, in pursuit of the well-being of its members as unique individuals, capable of reasoning, a characteristic that differentiates them from all other species. It is as a result of these events that humanity began to worry about establishing statutes, norms or laws to protect the integrity and welfare, both collective and individual; this is the principle that gives rise to human rights: human dignity. For Álvarez (2005), the concept of human dignity is related to the quality of dignity, referring to a deserved attribute or of which one is the subject of recognition, that is, it is an inherent attribute of the nature of man (Nava, 2012).

The historical facts that humanity has faced (two world wars, slavery, and civil wars, among others) constitute the history of human rights and have been the reason for establishing them as we know them. However, their recognition has become a difficult struggle, to the point that, over time, very few countries have recognized them as universal. In this way, the current concept of human rights is the result of a historical process positioned in different times and cultures, a gradual and fragmented process, with significant advances to date (González & Castañeda, 2011).

From this perspective, human rights are conceived, in a broad sense, as the group of ethical demands and values that have been adopted over the years and that are currently manifested in legal norms, both national and international. These norms give the state certain duties and, when considering human dignity as the supreme value, recognize a person's faculties. It is these obligations of the state that attribute significance to the study of human rights and their relation to it. Therefore, the different discussions and controversies involving the analysis of the essential aspects of human rights to understand, expand, and update the vision of what we know in the different social fields (political, social, ethical, and legal) (De Sousa Santos, 2014).

The construction of human rights has represented an important advancement in the

development of an organized society, which makes them one of the most important achievements in human history. Since their emergence, these rights have been conceptualized in different ways and have been granted various classifications that set a pattern for their recognition, that is, the legal formulation of certain rights over time. The conception and respect of human dignity, as well as the positivism of human rights before the state as a regulatory entity to guarantee them, led to one of the most important struggles for the state to promote and protect, but, above all, to respect and accept human rights as the path towards a democratic, free, and dignified society. (De Sousa Santos, 2014)

According to Bertha Solís García (n.d.), it is from the natural law that we can set the origins of human rights; this philosophical current presupposes the recognition of the dignity of the human being in relation to the activities of the state. In this stage, the first limits of the state activity in favor of the individuals were marked, since, from the Antiquity, in the despotic and absolutist regimes, the will of the governors was the supreme law and the governed had no defense mechanism, compelling them to obey and submit to the regime.

Since the creation of the United Nations in 1945, Mikel Berraondo (López & Vives Gracia, 2013) distinguishes four stages in the evolution of the recognition of human rights. He places the first from 1945 until the end of the 1960s, and characterizes it, on the one hand, as normative because numerous documents were approved in this period, among others, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Conventions, and the Pacts of 1966; on the other, he characterizes it as the internationalization of human rights. The second stage, according to this author, is framed from the end of the sixties until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a period he also calls institutional construction given the creation if institutional bodies and mechanisms of application (conventions), as well as non-governmental organizations dedicated to promoting and protecting human rights. He sets the third stage from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the attacks of September 11, 2001, a period in which the reference to third-generation rights is strengthened and the interdependence between peace, development, and the environment is discussed. Lastly, in the fourth stage, which extends from September 11, 2001, to the present, the obsession with collective security predominates; this places the enjoyment of rights at risk because the fight against terrorism supposes the erosion of the people's guarantees, that is, the protection of the HR is violated. (López & Vives, 2013).

The context of the 21st century, when the conquests of the 20th century are subject to revision, poses challenges for HR. For example, the fight against terrorism is being used as an alibi to repress social movements and citizen initiatives; this has led to a broad economic, social, and political crisis that questions the social rights conquered in the last century (López & Vives, 2013).

Definitions and characteristics of human rights

Establishing a unique and universal concept to define what is now known as HR has been a challenging task. In fact, there is no concept to define it. However, as it has been possible to observe, HR revolve around the respect for human dignity as the fundamental value on which any concept reverts. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 was the first instrument to approach their conceptualization. In said document, the General Assembly of the United Nations indicated that

they are inherent rights to Human Beings, and do not distinguish from nationality, sex, ethnic origin, color, religion, language or any other condition. We all have the same rights without any discrimination and these, in turn, are interrelated, interdependent, and indivisible. (Organización de las Naciones Unidas, 1948)

Each of the member countries coined this concept at the time as unique and universal. However, over the years, and with the development of new human needs, other authors have granted them different conceptions and classifications. As an example of this we can mention the conception offered by the jurist Hernando Valencia (2003) in his work Diccionario Espasa de derechos humanos, in which he refers to HR as "fundamental freedoms and guarantees of the human person that derive from their eminent dignity, which binds all of the Member States of the International Community, and marks the limit between barbarism and civilization" (Valencia, 2003).

Escobar (2005) refers to HR as the demand for abstention or action that derives from the dignity of the people and that are, in turn, recognized as legitimate by the international community, in a manner that compels their protection. In a somewhat different sense, Herrera Flores (2000) states that HR have a broader meaning than stipulated in declarations and pacts integrated by the juridical-institutional; for him, they are all those normative, institutional, and social processes that seek to consolidate the spaces of struggle for human dignity.

In turn, Megías Quirós (2006) broadens the concept and poses that HR are conduits of freedom and mechanisms of demand before power so that people can reach the maximum expression of human satisfaction, self-realization. However, in his conception of the term, he clarifies that this does not mean that as individuals who enjoy these rights we can perform any act, but only that which is within the sphere of freedom, that is, what is allowed for good-doing, and that, as such, we must exercise them responsibly (López & Vives, 2013).

In a broad context, it can be stated that HR are the set of rights and freedoms, with universal legal status, that protect people and groups against actions and omissions that interfere in the enjoyment of human dignity, with the freedoms and prerogatives that correspond to them.

They are inalienable, that is, they are inherent to people by their nature and cannot be waived or transferred to others, as they are not dismissible or cancelable. HR are outside of the sphere of the market, they have no price, but have value. They are also indivisible, a characteristic that indicates that they constitute a whole and that, as a whole, they are inseparable from each other. Therefore, the division of HR into civil, political, social, cultural, and economic, or their classification by generations, is only carried out for educational and conceptual purposes, but it cannot be used to prioritize some rights over others.

All rights have the same rank, the same importance, both in the international (members of the UN) and the national and local (States and organizations that work in their defense) context. Lastly, HR are interdependent and interrelated, which means that the exercise of one right is related to another; therefore, the denial of one right endangers the others. The indivisibility of HR requires defining each right in such a way that it is consistent with all the others so that the exercise of one right does not involve the infringement of another or others (Fernández, 2003, p. 188).

Other characteristics that have been recognized to HR over time is that they are absolute because they prevail over any other claim or moral or legal requirement unless the circumstance occurs that there is a collision between two or more rights (Megías Quirós, 2006 p. 207). They are inviolable; this refers to the illegitimacy of the violation of the rights of a person by a third party (whether individual, institution, company or state). They are limited, that is, no right is unlimited; the rights of one person are limited to those of another, that is, the rights of an individual are limited when they affect the rights of third parties. Finally, HR are granted the principle of progressivity because they have an expansive character; in the future, there will be new rights that are unimaginable today; therefore, they will have to be shaped or modified according to their progress (López & Vives, 2013).

Political philosophy of human rights: from the domestic to the international

The recognition of the effectiveness of HR in each historical moment has supposed the establishment of mechanisms for their protection and promotion, which have been applied in the international, regional and local or domestic environment. The iusnaturalist foundation of HR is based on the recognition of human dignity in a moral and axiological order, which gives rise to moral rights (Alexy, 2000). In counterpart, and in response to iusnaturalism, is the iuspositivist foundation, which grounds HR in the act of legislation, which is why, in this scheme, they are only accepted as HR those recognized by the state through legal systems. From this perspective, HR are not something inherent in the human condition; they depend on a set of laws and norms to guarantee them, as without a legal system it would be difficult to recognize and assert them (Alexy, 2000).

Consequently, it can be said that HR are legal powers of social self-realization, which correspond to all men by the mere fact of being men, on the basis of which they must be recognized in a general and permanent way by the different state legal systems. At this point, establishing that the intimate connection between HR and the state has generated the legal institutionalization of rights is undeniable. This process must be analyzed from two perspectives, from the international field, and the national or local level. According to Roberto Alexy (2000), the positivist analysis of HR must be carried out from a national framework, that is, in domestic law. For this author, states must establish regulatory frameworks and promote them abroad or in international institutions. According to Alexy (2000), there are three reasons for the transformation of HR in positive law: the compliance, knowledge, and organization argument.

In the compliance argument, HR as moral rights can be demanded, but it is also possible to morally condemn their violation. This argument is based on the existence and character of HR, as well as on the premise that their moral validity does not imply the individuals behavior before them. Therefore, this premise becomes one of the main reasons for transforming HR into positive law. The knowledge argument holds that the problem of HR lies in the abstraction of the understanding of the rights. This means that the application of HR to specific situations frequently generates problems of interpretation and weighting, which, in these cases, does not make the abstraction of HR debatable but its concrete judgment by virtue of the statutes, norms or laws already established by the states. In other words, the issue of knowledge also leads to the need for the law. Finally, the organization argument refers to negative rights, abstaining from intervening in life and freedom, and they are addressed to all (Alexy, 2000).

Positive law is necessary as a minimum right of subsistence, and the state, as a legal organization, is in charge of guaranteeing it. Therefore, law and the state must exist, not for the fulfillment of rights, but the existence of rights to assistance, addressed to certain addressees and fully constituted. For Roberto Alexy (2000), once the HR framework or context has been institutionalized and determined, at the domestic level, the promotion of these can be carried out at the international level. He argues that it is impossible to seek international protection if the behavior and direction of HR are not analyzed or studied domestically (Alexy, 2000).

Perception of human rights in Mexico: who promotes and guarantees the protection of human rights?

The conceptualization of HR in Mexico has occurred as a gradual transition through history. Mexico has a vital role within the stages of HR development because, as mentioned by Bertha Solís (n.d.), it was the first country to document -through the 1917 Constitution- fundamental rights, giving birth to a constitutional country with the first mechanisms of protection of human dignity (Solís, n.d.).

However, this acceptance went through a long process throughout Mexican history. According to the page of the National Commission for Human Rights in Mexico (CNDH, 2017), the earliest antecedent dealing with the protection of the rights of citizens is found in the promulgation of the Ley de Procuraduría de Pobres of 1847, written by Ponciano Arriaga, in San Luis Potosí. Other authors place the rise of the promotion of HR in the second half of the twentieth century as a national social demand concomitantly with the transformations arising in the international context, responding to the need to protect the rights of the governed before the public power (CNDH, 2017).

In the Mexican case, the creation of the CNDH, as the first instance of protection, constituted an approach to the institutionalization of HR for their promotion. As a direct antecedent of the CNDH, in 1989, through the Ministry of the Interior, the General Directorate of Human Rights was created. A year later, in 1990, the CNDH was created by a presidential decree as a decentralized agency of the Ministry of the Interior. Subsequently, in a reform published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación of 1992, the CNDH rises to constitutional status and acquires the legal nature of a decentralized body with legal personality and its assets. In 1999, this body was constituted as an institution with full management and budgetary autonomy and changed the name of the National Non-Jurisdictional System for the Protection of Human Rights to the National Commission for Human Rights. Following article 6, section IX, of its law, the CNDH has among its functions "to promote the study, teaching, and dissemination of human rights in the national and international sphere."

Concerning the State's responsibility in the respect for human rights, according to Alexy (2000), these must be established within an affirmative constitutional right, in which the state provides all the tools to guarantee, promote, and protect them (CNDH, 2017). On the other hand, González and Castañeda (2011) maintain that, in the process of institutionalization of HR, within the constitutional framework of the Mexican State, there are two important typifications: the individual's rights and the rights of the citizen. These authors also call attention to the importance of establishing the rule of law. According to Alexy (2000), the state represents has two crucial responsibilities: the promotion, and protection of rights. However, it is also the agent that sometimes violates fundamental rights through various mechanisms of suppression of rights.

González and Castañeda (2011) add that the effectiveness of the rule of law is an essential element for development. They also point out that there is still a long way to go and call for the awareness of citizens to influence change and help build the rule of law in a better way, so that the law constitutes the legal order for negotiation in a framework of conflict resolution and, in this way, consolidate a modern, democratic and effective political system for all sectors of the population (González & Castañeda, 2011).

Human rights in the state of Nuevo León according to the 2016 report of the CEDHNL

The State Commission for Human Rights of Nuevo Leon (CEDHNL) is the public and autonomous body in charge of generating HR public policies, as well as their promotion and protection in the state context. It also provides help and advice to citizens who have suffered a violation of their rights. This Commission was created in 1992 as a non-jurisdictional system for the protection of HR, with the purpose of responding to the needs of protection of the rights of the people before the authorities (CEDHNL, 2016).

The state of Nuevo León is the 19th entity that makes up the United Mexican States. It has an approximate population of 5,119,504 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2016). Sixty-five percent of the population has access to an educational institution; this number is in equal proportions for boys and girls; thus, it can be affirmed that there are equal opportunities for access to this right. In terms of health, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) shows a total of 66% affiliations from this state. However, despite advances in this area, there are still significant differences within the 51 municipalities that make up the entity.

The authorities that received the most complaints about alleged violations of HR in Mexico were government institutions such as the IMSS, the public security forces, the Ministry of Education, as well as public officials. The CEDHNL, in its report of activities of the year 2016, showed that a total of 10,927 complaints were received about alleged HR violations. Among the federal authorities are the IMSS and the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA) (CEDHNL, 2016).

Theoretical framework

Citizen perception of human rights in the metropolitan area of Monterrey

Discrimination violates one of the fundamental rights of individuals, the right to equality, which is enshrined in Article 1 of the Mexican Constitution. Discrimination is caused by the stereotypes generated by society concerning sexual preferences, ethnic origin, religion, and social status, among others. According to the National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico, conducted in 2010, Monterrey ranked as one of the cities where discrimination is the highest (CNDH, 2017). In 2016, a survey was conducted on citizen perception in the metropolitan area of the city of Monterrey to perceive the people's appreciation of HR and discrimination.

Methodology

This work, in conjunction with the Faculty of Political Science and Public Administration of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL) and the AC "Citizen Leaders," provides learning tools that, in the end, will help in the process of improving quality of life of the people of Nuevo Leon through the implementation of a culture of legality in which specific issues of substantial progress, proposals for action, and the application of said proposals are immersed.

A group of researchers from different academic bodies participated in this study, organized by the Research Subdirectorate of the Faculty of Political Science and International Relations of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL), the academic body of Public Administration, Political Science, Management and Educational Policy, Sustainable Development and Political Communication, and Public Opinion and Social Capital.

The application of the questionnaire was supported by the members of the academic bodies, scholars of the Master's program of Political Science and undergraduate students. These students participated in the coding of the database, which was later used by the researchers, members of each of the academic bodies, to perform the analysis. The instrument included different items of different topics, distributed in a questionnaire that had already been applied by other institutions, as described below.

The HR variable was established based on the questionnaire of the National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico. This instrument was directed at young people and focused on perception, attitudes, and values concerning discrimination and its impact on the HR of people belonging to groups in situations of vulnerability and discriminated because of their religion, their sexual orientation or their ethnic or cultural features (Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud, Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación, 2010). It is important to mention that in some items it was necessary to make changes to adapt them to the needs of the study context.

The random sample consisted of 493 interviewees from the city of Monterrey, men and women over 18 and approximately 40 years of age. The median income of the participants was between five and six minimum wages. Forty-three percent of the respondents were male, and 57% were female. Forty-six percent of the interviewees had undergraduate studies or were studying at the university. The participant's marital status was made up of 47% married and 35% single.

The questionnaire is made up of five variables, including the HR variable. These variables include 41 items distributed in different types of questions: three open, fourteen dichotomous, ten multiple-choice, and 40 Likert scale (Arango Morales, Leyva Cordero, Marañón Lazcano, & Lozano Treviño, 2016). The questionnaire begins with sociological data (age, sex, education, marital status).

Analysis of results

The following is the analysis of the perception that citizens of the metropolitan area of Monterrey have regarding HR. Also, the government's capacity to promote and protect HR is taken into consideration, among other topics.

According to the data obtained during the study, several tables were prepared to facilitate the interpretation of the information obtained from the 491 respondents. It must be borne in mind that, as mentioned above, that the state plays one of the most important roles in the promotion and protection of HR; however, it is also the main perpetrator of their direct or indirect violation. The first question related to HR in the survey was "In your opinion, do the authorities respect human rights?" (Table 1).

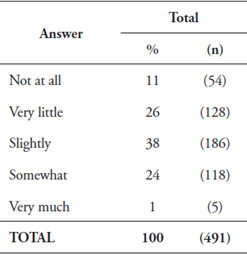

Table 1 In your opinion, do the authorities respect human rights?

Source: created by authors based on the data obtained from the survey Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana (Arango et al., 2016).

As noted, 75% of respondents indicate that municipal authorities have very little or no respect for HR. Thus, the public's perception is that there are not enough mechanisms to protect HR in the municipality and that, besides, the government generates no respect for them.

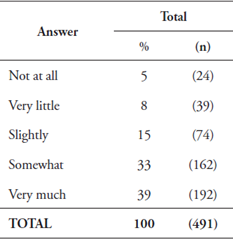

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the question "Do you think that people are discriminated against, treated badly or unfairly because of their physical appearance, social class, sexual preferences, skin color, gender (female), indigenous origin or aspect, political preference or religious beliefs?" (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 Physical appearance

Source: created by authors based on the data obtained from the survey Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana (Arango et al., 2016).

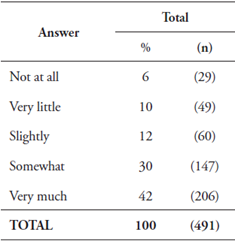

Table 3 Social class

Source: created by authors based on the data obtained from the survey Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana (Arango et al., 2016).

Tables 2 and 3 show that there is discrimination on the part of society based on physical appearance and social class. According to the data, 39% of respondents indicated that there is a high level of discrimination because of physical appearance, while 42% agree that there are abuse and discrimination regarding social class.

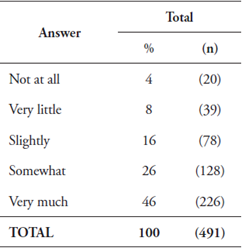

Table 4 shows that 46% of respondents believe that there is a high level discrimination on the part of the authorities and society regarding sexual preferences.

Table 4 Sexual preference

Source: created by authors based on the data obtained from the survey Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana (Arango et al., 2016).

Table 5 shows that 63% of respondents say that there is high or some discrimination and mistreatment based on belonging to the female gender. Given this result, it is evident that in the municipality there is a problem of gender violence, in which the woman is in a vulnerable state concerning the protection of her rights.

Table 5 Gender (female)

Source: created by authors based on the data obtained from the survey Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana (Arango et al., 2016).

Other results obtained refer to discrimination on the part of government institutions and of society. Fifty-one percent of the respondents indicated that discrimination is high regarding indigenous origin or aspect. In contrast, 47% indicated that political preference and religious beliefs are not significant factors linked to discrimination. From these results, it can be said that there is respect towards the freedom of expression and grouping regarding these issues by the authorities and society. Finally, regarding skin color, 28% of respondents said that there is a high level of discrimination and abuse concerning these factors.

Conclusions

Around the world, many people suffer HR violations, one of its strongest manifestations is discrimination, which also involves society and government. According to the analysis, it is concluded that the citizens of the municipality of Monterrey perceive as very little or slight the respect of the authorities towards HR. Therefore, this should be a focus of attention not only for the state but for the government system of the State of Nuevo Leon, as well as its citizenship to prevent it from becoming a major problem.

Another focus of attention has to do with gender violence, which, as noted, exists between the population and women, a situation that unfortunately places them as one of the most vulnerable groups in the area of HR.

It was also found that there are discrimination and mistreatment towards indigenous people even by the authorities within the same community. Fifty-one percent of the respondents indicated that there is a very high level of discrimination because of indigenous origin or aspect. There was also a very high level of discrimination and mistreatment because of the sexual preferences of the individuals in the municipality. This draws attention to the need for the authorities to establish defense mechanisms for the gay, lesbian-gay, bisexual, transgender, transvestite, transsexual, and intersex (LGBTTTI) community, a group that is identified as vulnerable in terms of their rights.

Finally, it was established that there is very little discrimination concerning the religious beliefs and political preferences of the citizens, which shows protection and respect on the part of the authorities and civil society for both the freedom of religion and expression and association.

Following this context of study and analysis, it can be affirmed that a social culture of discrimination exists in the society of Nuevo León given the presence of entrenched stereotypes for men and women. This allows us to visualize the problem of human rights, in particular, the right to equality and non-discrimination. Although discrimination is prohibited in Mexico, there is still a need to legislate on this matter to achieve a cultural, social, and legal change.

REFERENCES

Alexy, R. (2000). La institucionalización de los derechos humanos en el Estado constitucional democrático. Derechos y Libertades, Revista del Instituto Bartolomé de las Casas, 8, 21-41. [ Links ]

Álvarez Álvarez, A. (2005). Jurisprudencia Sala Constitucional (t. 2). Caracas: Ediciones Homero. [ Links ]

Arango Morales, X., Leyva Cordero, O., Marañón Lazcano, F., & Lozano Treviño, D. (2016). Cultura de la legalidad ciudadana. Análisis sobre el caso de Monterrey. Monterrey: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. [ Links ]

Comisión Estatal de Derechos humanos Nuevo León (CEDHNL). (2016). Informe de actividades de la Comisión Estatal de Derechos humanos de Nuevo León. Monterrey: CEDHNL. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de los Derechos humanos (CNDH). (2017). CNDH-Conócenos. La CNDH. Antecedentes. Recuperado de www.cndh.org.mx/antecedentes. [ Links ]

De Sousa Santos, B. (2014). Derechos humanos, democracia y desarrollo. Bogotá: De justicia. [ Links ]

Escobar G. (2005). Introducción a la teoría jurídica de los derechos humanos. Madrid: Trama Editorial. [ Links ]

Fernández, E. (2003) Igualdad y derechos humanos. Madrid: Tecnos. [ Links ]

González, M., & Castañeda, M. (2011). La evolución histórica de los derechos humanos. México: Comisión Nacional de los Derechos humanos en México. [ Links ]

Herrera Flores, J. (2000) El vuelo de Anteo: derechos humanos y crítica de la razón liberal. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer. [ Links ]

Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud, Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación. (2010). Encuesta nacional sobre discriminación en México (ENADIS 2010). Resultados sobre las y los jóvenes. México, D. F.: Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2016). Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015, Nuevo León. Aguascalientes: INEGI. [ Links ]

López López, P., & Vives Gracia, J. (2013). Ética y derechos humanos para bibliotecas y archivos. Salamanca: Federación Española de Asociaciones de Archiveros, Bibliotecarios, Arqueólogos, Museólogos y Documentalistas (Anabad). [ Links ]

Megías Quirós, J. (2006) Manual de derechos humanos: los derechos humanos en el siglo XXI. Cizur Menor, Navarra: Thomson-Aranzad. [ Links ]

Nava, J. G. (2012). Doctrina y filosofía de los derechos humanos: definición, principios, características y clasificaciones. Razón y Palabra, 17(81), 4-30. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU). 1948). Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos. Recuperado de https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/spn.pdf. [ Links ]

Solís García, B. (s. f.). Evolución de los derechos humanos. Recuperado de https://archivos.juridicas.unam.mx/www/bjv/libros/7/3100/9.pdf. [ Links ]

Valencia, H. (2003). Diccionario Espasa derechos humanos. Madrid: Espasa. [ Links ]

To cite this article: Gutiérrez Felipe, R., & Arango Morales, X. A. (2019). Citizen perception of human rights: the case of Monterrey, Nuevo León. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 17(25), 131-145. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21830/19006586.138

The articles published by Revista Cientifica General Jose Maria Cordova are Open Access under a Creative Commons license: Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode

Disclaimer The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest related to the article. The data was obtained from the case study of Culture of citizen legality, in Monterrey.

About the authors

Ricardo Gutiérrez Felipe has a degree in International Relations. He is currently a collaborator of the Clúster de Turismo de Nuevo León AC, which promotes tourism in Nuevo León through the private initiative, the government, and the academy. He is also a candidate for a Master's degree in International Relations. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2496-1853, contact: ricardo.gutierrezfe@uanl.edu.mx

Xóchitl Amalia Arango Morales holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy of Political Science. She is a full-time graduate and postgraduate professor at the Faculty of Political Science and International Relations of the UANL. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0907-452X, contacto: xochitl.arangomr@uanl.edu.mx

Received: May 15, 2018; Accepted: December 17, 2018; other: January 01, 2019

texto em

texto em