INTRODUCTION

In February 2020, the World Health Organization gave a name to a previously unknown infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 novel Coronavirus 1. This condition, which became known as COVID-19, quickly evolved into a global pandemic that, by mid-October 2021, had caused over 4.9 million deaths and infected over 241 million people worldwide 2. In addition to its exponentially growing morbidity and mortality rates, COVID-19 changed the lives of millions of people resulting from unprecedented stay at home orders and the closure of businesses, schools, and universities 3.

Research has suggested that people's inability to carry out their daily activities has a direct impact on their lifestyle and could lead to negative health outcomes in the future. Physical inactivity, for instance, could lead to overweight and obesity, and altered sleeping patterns can lead to stress and anxiety 4-6. During the pandemic, both normal and leisure time physical activity were reduced, and rates of a sedentary lifestyle increased as a result of lock-down efforts in many countries 7-9.

The literature also suggests that chronic stress from unexpected events, limited social support, and diminished levels of self-control, have adverse impacts on the mental and physical well-being of populations 10-12. The prevalence of mental disorders, including depression, anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, irritability, and anger, show themselves, and tend to double, during states of emergency. While most people will return to normal cognitive states over time, interventions must be available to assist those experiencing crises during these situations 13,14

While COVID-19 has negatively impacted the physical, mental, social, economic, and spiritual well-being of people around the world, it has been hypothesized that college age-populations have been hit especially hard 8,15-19. While morbidity and mortality rates have been relatively low among this population group, COVID-19 has significantly affected their lifestyle. In many parts of the world, universities were forced to close, and students were sent home, which ended not only educational opportunities, but also employment and social events. Concurrently, instruction modalities were modified with students learning new technologies and facing challenges such as access to computers or reliable internet connection 20.

Given the sudden lifestyle change, it is not surprising that social isolation, feelings of perceived hopelessness, and uncertainty about the future have affected college students' ability to perform their daily activities. College students report changes in eating patterns due to difficulties accessing nutritious meals or not having sufficient money to purchase food. In addition to changes in their nutrition and physical activity patterns, the literature has found changes in college students' sleep patterns and their emotional and physical well-being 9,16,18,19,21-23.

The literature suggests that social isolation could also affect the mental health of university students 17,24, and, hence, academic performance 25. Similarly, academic performance is influenced by the engagement that students provide 27, which is influenced by three aspects: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive 28. Another indicator of mental health is orientation to happiness, which is defined as the propensity to perform activities that provide happiness in three distinct domains: pleasure, meaning, and engagement 26.

Most research about the impact of COVID-19 on college-aged populations has been conducted among North American and European groups, which has left a large gap in knowledge regarding Latin American populations. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of COVID-19 on lifestyles, orientation to happiness, and student engagement among a sample of college students in Mexico, El Salvador, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Peru, and the US, to expand this knowledge across different geographic locations. Three research questions guided this study: How have students' health behaviors changed since COVID-19 started? How has student engagement changed since COVID-19 started? How has students' orientation to happiness changed since COVID-19?

METHODS AND MATERIALS

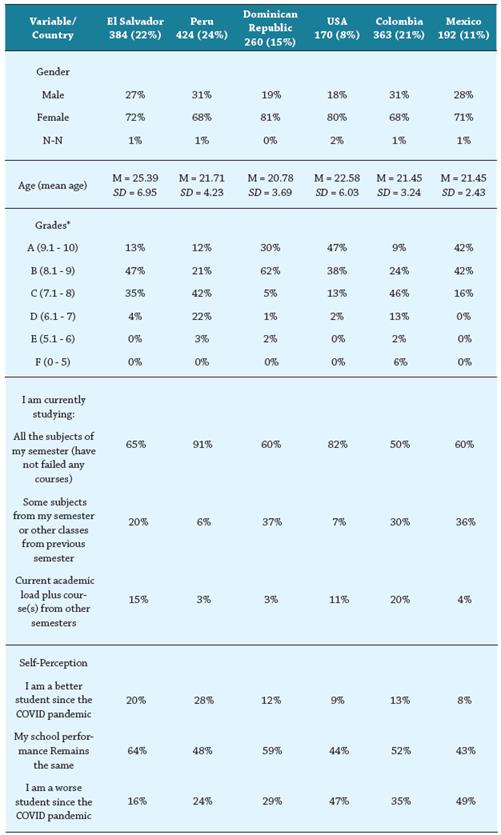

Data for this cross-sectional study were collected using the Qualtrics platform from 1764 students in Mexico, El Salvador, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Peru, and the USA (see Table 1). Sample respondents included public and private institutions, rural and urban centers, and medium to large schools. The study methods were approved by Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating institutions, and participants electronically signed an informed consent form before answering the questions.

Table 1 Demographic Results

* Not every country uses the A-F grading system. The numeric values provide equivalent grades for those countries not using an alpha grading system

Data for this study were collected using the three scales described below which have been validated in previous studies. Demographic questions included gender (which provided a forced choice between male/female/non-binary), age, country, career, semester, and global grade (approximate).

Data on lifestyle changes were collected using the Student Health Behavior Inventory 29, which asks prospective questions related to student lifestyles during the pandemic. The SHBI has an internal consistency of .81 using Cronbach's alpha. The scale presents 13 items grouped into three categories: food consumption (i.e., how has your fat consumption changed during this quarantine period?), physical activity (i.e., what changes have you made during quarantine in terms of physical activity or sports?), and alcohol & tobacco use (i.e., how has your alcohol use changed during the quarantine?). Each item required responses on the Likert-type scale to which the item was applied. All the questions were adapted for the COVID-19 era.

The Orientations to Happiness Scale 26 was used to collect data related to their orientation to happiness. The scale has 18 items divided into three domains: Life of pleasure (i.e., I love to do things that excite my senses), life of meaning (i.e., my life serves a higher purpose), and life of engagement (i.e., I seek out situations that challenge my skills and abilities). The response scale ranged from 1 (very much unlike me) to 5 (very much like me).

The University Student Engagement Inventory was used to measure behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement; some questions were adapted for the COVID-19 era 25. Scales presented 15 items divided equally into three dimensions: behavioral (i.e., when I have doubts I ask questions and participate in debates in my virtual classes), emotional (i.e., I am interested in the activities that I do virtually), and cognitive (i.e., I try to integrate the acquired knowledge in solving new problems). Participants responded using a scale that ranged from 1 = never to 5 = always.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS, 24 version. Frequency distribution from all the questions was obtained and a chi-square analysis was performed to assess differences between the variables.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the Demographic characteristics of the study participants. The majority of students were female (72%), ages ranged from 17 to 60 (M = 22.38; DE = 4.99). Self-reported grades were better in the USA (85% reported grades of B or better) and lower in Colombia (33% reported grades of B or better). Finally, the vast majority of students reported their academic performance remained the same (53%) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, participants from the USA and Mexico reported a higher perception of having worse academic performance since the pandemic began.

Table 2 presents the results of lifestyle changes regarding food consumption. Most sample participants reported a change in their food consumption (56% X2 = 27.93, df = 5, p < .001). Study participants in El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia were more likely to report food consumption changes as a result of the quarantine (X2 = 40.21, df = 5, p < .001).

Differences were also observed regarding the type of changes with some countries reporting positive changes (increased rates) in regard to consumption of vegetables (X2 = 75.71, df = 10, p < .001) and fruits (X2 = 42.18, df = 10, p < .001). No changes were reported regarding bread consumption ( X2 = 65.52, df = 10, p < .001); rice (X2 = 64.22, df = 10, p < .001); and number of meals (X2 = 60.96, df = 10, p < .001). Finally, negative outcomes were reported regarding fat consumption (X2 = 68.85, df = 10, p < .001), and white sugar (X2 = 64.83, df = 10, p < .001).

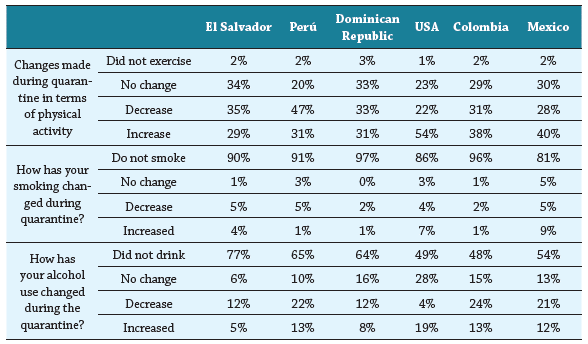

Table 3 shows results in lifestyle changes regarding physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol use. Most students reported being physically active during the pandemic with less than 4% indicating they did not exercise at all (from a low of 1% in the US, to a high of 3% in the Dominican Republic). Similarly, many study respondents indicated no changes in their physical activity during the quarantine period. Statistically significant differences were found among the responses to changes in physical activity during the quarantine period (X2 = 102.36, df = 15, p < .001). Students who reported a higher increase during the quarantine were from Colombia, Mexico, and the USA.

As with physical activity, the vast majority of respondents did not indicate changes in their tobacco use during the lockdown period (over 80% in all countries). Similar results were found for alcohol use (from a low of 48% in Colombia, to a high of 77% in El Salvador). Statistical differences, however, were found in the use of tobacco (X2 = 79.83, df = 15, p < .001) and alcohol (X2 = 167.67, df = 15, p < .001), with the US and Mexico reporting higher rates in those categories.

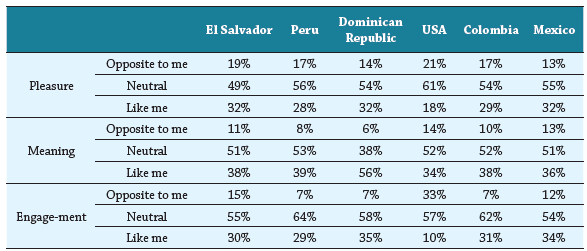

Table 4 shows the results from the Orientations to Happiness Scale. Responses along the three scale domains (pleasure, meaning, and engagement) were mostly neutral except for students in the Dominican Republic, who reported higher values on the answer "like me." A difference was also observed among US students who reported "like me" on the pleasure and engagement dimensions. Chi-square analysis indicated no significant differences among the six countries on the domain pleasure (p > .05); however, the students reported different values on eudemonic (X2 = 35.19, df = 10, p < .001) and engagement (X2 = 104.84, df = 10, p < .001).

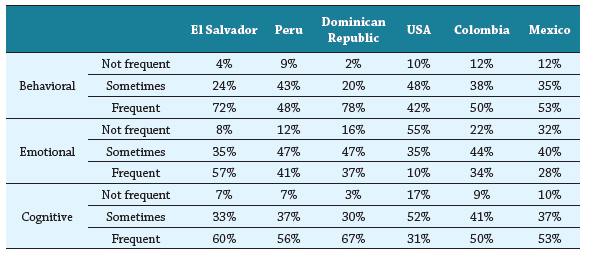

Results from the University Student Engagement Inventory are presented in Table 5. Chi-square analysis revealed that the responses of the six countries are significantly different on the behavioral (X2 = 123.96, df = 10, p < .001), the emotional (X2 = 235.05, df = 10, p < .001), and the cognitive domains (X2 = 64.65, df = 10, p < .001). Students from the six countries reported less frequency in emotional engagement and higher on the behavioral dimension. This finding was true, except for students in Peru and Colombia, where pupils indicated a more frequent cognitive engagement.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 abruptly changed teaching and learning modalities in higher education; changes that will persist for many years to come. In addition to closing institutions of higher learning, COVID-19 also forced changes in student lifestyle, engagement in learning activities, and their orientation to happiness. Even before COVID-19, little comparative research existed about student lifestyle, orientation to happiness, and student engagement 30. This study helps fill the void in these three areas.

Results from this study show that students' physical health domain suffered some changes during the pandemic era, especially in food consumption. The responses on the Orientations to Happiness Scale indicated a neutral tendency of the students to obtain happiness, while the academic engagement maintained a medium-high level. All the chi-square analyses showed that the responses were different among the six countries (except for pleasure). This finding makes the pleasure domain important in future research related to Orientations to Happiness and Student engagement.

Limitations for this study include a lifestyle scale with limited domains and no questions about specific non-health related issues faced by study participants. Similarly, the social isolation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic may have adversely affected study participants' engagement and orientation to happiness. Furthermore, the electronic nature of the instruments might have reduced participation due to technology fatigue experienced by students by the time this study was conducted a year into the pandemic.

The preceding limitations notwithstanding, data from this study suggest the COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered student lifestyles, both directly and indirectly. Students were, overnight, faced with changes in learning modalities that were of an emergent nature, meaning most institutions of higher learning lacked a comprehensive plan to move from in-person to remote learning. Faced with limitations related to employment, communication, privacy, technology challenges 31, distress 15,16, and uncertainty related to how the pandemic might impact them, student engagement was no doubt affected. In fact, Roman (2020) concluded that "...institutions of higher learning have focused on safeguarding the continuity of the courses, without knowing what the real obstacles are within the new didactic contexts that have originated from starting from the health contingency." (p.36). This lack of information has, no doubt, had a negative impact on student engagement.

CONCLUSIONS

Several lessons may be learned from the ongoing pandemic as it relates to the physical and mental well-being of students. The changes in students' lifestyles, orientations to happiness, and engagement indicate the impact the pandemic from COVID-19 had across the USA and Latin America.

Institutions of higher learning should take steps to address the physical and mental health needs of their students. The imminent return to "normal" will require students to be prepared to return to in-person learning, address their nutritional and physical activity needs, and also consider strategies designed to decrease the use of tobacco and alcohol.

Finally, institutions of higher learning should be ready to utilize their greatest capital -- their student bodies -- to deliver education, health, and mental well-being training to their communities in an effort to decrease pandemic-related anxieties and increase their orientation to happiness and engagement.

Future research should focus on the impact of pleasure on lifestyle changes, student engagement, and their orientation towards happiness. Additional research could focus on the impact of stress (which was not included in this study), and lifestyle changes, orientation to happiness, and student engagement.