1. Introduction

Banana (Musa spp.) is one of the most widely grown fruits in the world and a major food source for the planet’s population. Its cultivation in the semiarid usually requires irrigation to meet crop water requirements (e.g., [29]). Moreover, several authors have reported high water consumption for a range of banana cultivars in different soil and climate conditions (e.g., [10-12]).

[25] emphasize the importance of studying soil temperature, since it will be affected by predicted changes in global temperature. Recent studies show that every 1 °C increase in air temperature raises the associated soil temperature by 1.5 °C. Changes in soil temperature may impact the regulation of the plant physiological process. [24] state that temperature regulates gas exchange on the surface, affects the movement, viscosity and density of soil water and, consequently, water and nutrient absorption by plants, thus influencing most soil physical, chemical and biological processes.

The Brazilian semiarid is subject to frequent droughts. In particular, the present study was conducted during the 2014-2015 drought, which was severe and affected a large area of Northeast Brazil, with significant impacts on the population and economic activities, as reported by [5].

Mulching provides greater hydraulic roughness, increasing water infiltration into the soil and reducing surface runoff velocities and, consequently, soil losses. This protects the soil surface from the direct impact of raindrops, thereby reducing surface crusting, compaction, splash erosion and water evaporation and controlling soil temperature fluctuations, particularly during dry periods (e.g., [1-8,17,20-22,27,39]).

Among the different organic materials used as mulch, coconut coir dust, a by-product from the coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) industry, is known to be efficient in controlling runoff and soil loss (e.g., [17,20,38]). Coir is an inexpensive, highly durable natural fiber that biodegrades slowly.

In semiarid locations, mulching can benefit irrigated crops by improving water use efficiency and fruit physical and chemical properties (e.g., [9,35]). Moreover, irrigation contributes to temperature regulation, helping boost agricultural production [16,33] as a direct result of soil moisture availability for evapotranspiration.

[24] report that temperature regulates gas exchange at the soil surface, affecting water and nutrient absorption by plants and influencing chemical and biological processes. Mulch cover lowers the maximum soil temperature and temperature range when compared to a bare surface [6].

As such, mulching may be relevant for soil physical amelioration, soil temperature control, and water conservation. However, the type and cover density of mulch may have different effects, depending on crop stage, soil type, and climate conditions. [14] adopted 4-6 t ha-1 straw mulching in semiarid Nigeria and observed an improvement in soil physical properties. [37] used 9 t ha-1 bean straw mulching in a highly heterogeneous alluvial valley in northeastern Brazil (the same soils used in the present study) for carrot (Daucus carota) production, with micro sprinkler irrigation. Mulching at a 9 t ha-1 cover rate was efficient in conserving soil moisture and decreasing soil moisture spatial variability. Later, [21] used soil flumes in a laboratory and found that 2 and 4 t ha-1 of rice straw mulch was efficient at lowering soil temperature and raising soil water content. Although the conditions described in this paragraph differ from those of the aforementioned study (e.g., in terms of mulch type, soil physical characteristics, plantation pattern and water application regime), they show a general trend in terms of mulch effects.

Comparing different mulch materials (coconut coir and cashew leaves, among others) and densities, [16] conducted an in-depth field study in semiarid Brazil and found that 4 t ha-1 of coconut mulch was effective at controlling temperature fluctuations and enhancing soil moisture under natural conditions. On the other hand, in a detailed investigation in the same alluvial valley studied here, [26] used geostatistics and Beerkan Infiltration Tests and observed high spatial cross dependence between soil physical characteristics and hydraulic properties. The authors recommended adopting soil management techniques to support irrigation management in areas with low infiltrability. In this respect, the present study aimed to analyze the impact of mulching cover as a management alternative in low infiltrability zones.

Thus, an in-depth short-term field experiment was conducted in an irrigated plot in the semiarid (near the location studied by [16] and [26]), to investigate the impact of i) different coconut coir mulch densities on surface temperatures and ii) temperature and soil moisture dynamics for different soil depths under 4 and 8 t ha-1 mulch treatments, in a drip irrigated banana plantation with low rainfall input in an area with low infiltrability. Although several studies have been conducted on drip irrigation under artificial and natural mulch (e.g., [34,35,40]), loose coir mulch (e.g. coir dust) applied on bare soil has not been sufficiently investigated in terms of controlling soil temperature and moisture, since most research focuses on soil erosion issues. This type of thermal/moisture study had yet to be conducted on banana plantations in Brazilian semiarid alluvial valleys, particularly during a period of severe drought.

2. Materials and methods

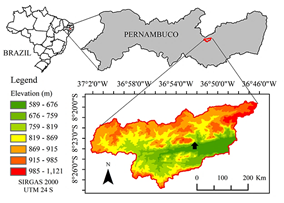

The study was carried out on Mimosa farm in the Mimoso District of the municipality of Pesqueira, Pernambuco state (Brazil), at 08° 10' S and 35° 11' W and an altitude of 613 m (Fig. 1). The farm is located in the alluvial valley of the Ipanema River, where small-scale irrigated community farming is carried out. Climate in the region is BSh (extremely hot, semiarid) according to the Köppen classification, with average annual rainfall, evapotranspiration and temperature ~700 mm, 1600 mm and around 25°C, respectively (e.g., [19]). Monitoring was carried out during a severe prolonged drought, according to [4].

Source: The authors

Figure 1 Location of the study site in the Mimoso alluvial valley, Pesqueira, Pernambuco state (Brazil), in the Alto Ipanema basin.

Soil in the study area is characterized as Fluvic Neosol. Based on the [30] soil analysis manual, the soil profile is classified as sandy clay loam (USDA Soil Texture Triangle), consisting of ~59% sand, ~24% clay and ~17% silt. Soil bulk density is ~1.47 kg m-3, porosity ~0.52 m³ m-3, hydraulic conductivity ~0.05 mm s-1, and soil moisture content at field capacity ~0.28 m3m-3. Detailed infiltration tests have been carried out in the area [26]. Hydraulic conductivity in the zone selected for the irrigated plot was ~0.03 mm s-1.

The Prata banana cultivar was grown in 4 m × 4 m regular spacing. At the time of the study, the plantation was already in the production phase (Fig. 2).

A drip irrigation system was used, with simple rows and 0.20 m spacing between drippers, flow rate of 1.25 L h-1 and working pressure of 98.06 KPa. Irrigation began on November 27, 2014, one day before the soil temperature and moisture measurements. Water was pumped from a shallow water table well (large diameter well) in an unconfined aquifer with 0.90 dS m-1. The water table was estimated once during the study period ~2.5 m below ground level, using an electronic measuring tape.

The irrigation depths applied were based on crop evapotranspiration (ETc), estimated from daily readings in Class A evaporation tank (Class A), using a tank coefficient of ~0.75 and crop coefficients (Kc) in accordance with [9].

Six thermocouples and 3 soil moisture probes were installed and connected to a Datalogger. Soil temperature was monitored by the thermocouples every 10 minutes. Soil moisture dynamics was measured with CS616 sensors (Campbell Scientific), also at 10-minute intervals. The experiments were carried out from November 28, 2014 to March 24, 2015, during the dry season and under a severe multiannual regional drought. Average temperature during the experimental period was ~25 °C.

Temperature variability was evaluated under 3 ground cover conditions: bare soil, and coconut coir dust at 4 and 8 t ha-1. The mulch was not spread directly onto the ground surface. Instead, two 1 m² wooden frames with a thin flexible mesh screen were used to prevent the material from passing through and facilitate access to the sensors. The different coir dust densities were placed on the screens and the frames positioned over the soil surface. Coir dust was pre-washed and dried at ambient temperature. Fig. 3 shows a diagram of the field setup. Both mulch support frames had approximately the same sun exposure.

Source: the authors

Figure 3 Diagrams of the field experimental setup, showing the frames used to support coir mulch in the 4 and 8 t ha-1 treatments. Ti and θi are the temperature and moisture measuring points below the 4 t ha-1 mulch, respectively, and Ts the surface temperature measuring point. The diagram is not to scale.

Soil temperature for the 4 t ha-1 experiments was measured on the surface (Ts), and at depths of 0.10 m (T1), 0.30 m (T2) and 0.50 m (T3). For the 8t ha-1 treatment, temperature was only measured at the surface (Ts8). Air temperature data were obtained from an automated weather station close to the study site. Soil moisture content was measured at depths of 0.10 (θ1), 0.30 (θ2) and 0.50 m (θ3), but only for the 4t ha-1 treatment, and as such, the CS616 sensors were placed alongside the thermocouples to establish the relationship between soil moisture and temperature. The probes used to monitor soil moisture were calibrated in the field using a gravimetric method. The methodology and calibration equations for the CS616 probes are in line with [32].

The daytime (6:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.) and nighttime periods (5 p.m. to 6 a.m.) were established based on solar radiation data from the weather station (approximated to the hour).

Statistical analysis was performed to assess the significance of the soil moisture and temperature variations and relate them to the daytime and nighttime periods at the different depths studied. The experimental results were submitted to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and when significant, means were compared using Tukey’s test at 5% significance. The variables were submitted to regression analyses, with significance determined by the F-test (p< 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Temperature at the soil surface

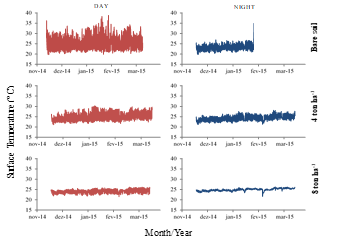

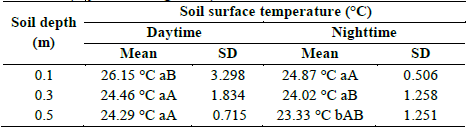

Fig. 4 shows the time series for daytime and nighttime temperature at the surface for the three soil cover conditions (i.e. bare soil, and mulch densities of 4 and 8 t ha-1). Coconut coir dust applied to the soil surface reduced the maximum soil temperature and temperature fluctuation (3% for 4 t ha-1; 9% for 8 t ha-1), regardless of mulch density. The higher the mulch density the greater the dampening effect at the surface when compared to bare soil. Soil surface temperature differed significantly in relation to mulch density, with lower temperatures observed during the day and increased temperatures at night at the highest density (Table 1).

Table 1 Soil surface temperatures (mean and standard deviation, SD) for three mulching scenarios: bare soil, 4 and 8 t ha-1 mulch cover (daytime and nighttime).

Note: Means followed by the same uppercase or lowercase letter do not differ at 5% probability according to Tukey’s test. Lowercase letters compare daytime and night-time values and uppercase letters compare temperatures for three mulching scenarios: bare soil, 4 and 8 t ha-1.

Source: The authors.

Source: The authors

Figure 4 Time series of soil surface temperatures for three mulching scenarios: bare soil (top), 4 t ha-1 (middle) and 8 t ha-1 (bottom) mulch cover, during the day (left) and at night(right).

The buffer zone created by the mulch prevented soil temperature from rising during the day and falling at night. The 8 t ha-1 mulch density produced the lowest average daytime temperature and the highest nighttime temperature. Similar results were obtained by [40], who analyzed the effect of rice straw mulch on soil temperature in irrigated vine cultivation in the Loess plateau, China, and found that the mulch reduced soil temperature during warmer periods and kept it higher in colder periods when compared to bare soil. [28] studied 4 different mulch types (wood dust, wood chips, dry grass (Cynodon spp.) and rice straw) in carrot cultivation and observed statistically significant differences. On average, the mulches maintained a soil temperature gradient about 3.5oC lower than that obtained without cover and a moisture content 2.0% higher than bare soil.

3.2. Soil temperature and moisture content

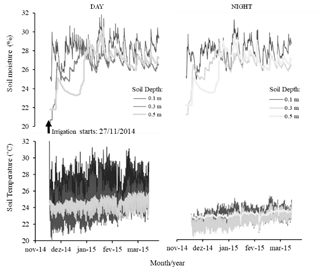

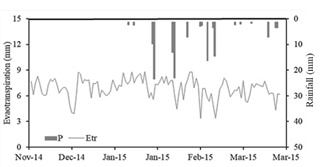

It has been reported that mulch cover reduces the temperature fluctuation range at the soil surface, meaning soil moisture must also be affected. [33] observed that soil moisture in Pernambuco state (Brazil) varies considerably over time as a function of soil properties and cover. Understanding soil moisture dynamics on a spatial and temporal scale is vital in agricultural planning and soil management because soil moisture content is one of the most important variables in climatological and hydrological research, with involvement in infiltration, irrigation and drainage [3]. Fig. 5 shows the chronological variation of soil moisture and temperature under coir dust mulch at 4 t ha-1 for different soil depths. Soil water content ranged from ~21% (when monitoring began, the day after drip irrigation onset) to ~32% (after rainfall spells), with soil moisture stabilizing around 30 days after drip irrigation onset. The decline in soil temperature due to mulch is associated with soil moisture dynamics. The highest moisture values were recorded in late January and early February 2015. During this period, rainfall events of ~107.5 mm were distributed over several days (Fig. 6).

Source: The authors.

Figure 5 Time series of soil moisture and temperature at three depths: 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m, during the for day and at night. The irregular initial soil moisture conditions are due to rainfall.

Source: The authors

Figure 6 Rainfall (above 1 mm) and evapotranspiration at the experimental site (3 months in 2014/2015).

In the same region (Mimoso District, Pernambuco, Brazil), albeit using different crops with different root systems, [37] reported that mulching increased soil moisture availability and reduced temporal soil moisture variations in carrots (Daucus carota). [31] validated a previous study by [37], whereby a 9 t ha-1 mulch density increased soil moisture in a cabbage plot, and [4] found that mulching in experimental plots significantly increased soil moisture and improved production in rainfed corn (Zea mays) plantations.

Working with coconut dust mulch, [18] concluded that the mulch modified the soil surface temperature pattern by reducing its daytime variation in relation to bare soil, at different soil depths, especially near the surface. The mulch acted as a thermal insulation layer, meaning that the soil warmed up less during the day and lost less heat to the atmosphere at night.

As expected, at night, without direct solar radiation, soil temperatures fell in all the scenarios tested. A mulch density of 4 t ha-1 caused a significant change between daytime and nighttime temperatures, promoting a buffer effect for soil temperature fluctuation. [24] adopted different mulch densities on the soil surface and found that mulch reduced the maximum soil temperature by up to 3 oC. [13] concluded that the behaviour of the soil temperature over 24-hours was similar for all the days studied, with the smallest temperature variation always recorded at a depth 0.40 m and the largest in the surface layers, regardless of cover conditions, under two black oat mulch densities (4 and 8 t ha-1).

In order to examine the relationship between air and surface temperatures under different coir dust mulch densities, a scatter plot was produced to explore tendencies and correlations between these variables. The degree of association between variables was evaluated for daily data. Plotting air temperature against soil temperature showed no correlation (Fig. 7); the presence of mulch produced far less data scatter when compared with bare soil conditions (for surface temperatures) and at greater depths.

During the day, the soil surface (0.1 m depth) showed a greater correlation than the 0.3 and 0.5 m layers. This is due to the natural solar radiation process, since heat exchange between the soil and the atmosphere is greater nearer to the surface.

Table 2 summarizes soil temperature data at different depths, showing a tendency to decrease with increasing soil depth because the soil layer above reduces temperature variations. These results corroborate those of [15], who studied the influence of mulching on soil temperature and moisture content in corn (Zea mays) grown in the Loess Plateau, China.

Table 2 Mean and standard deviation (SD) of soil temperature at depths of 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m (daytime and nighttime).

Note: Means followed by the same uppercase or lowercase letter do not differ at 5% probability according to Tukey’s test. Lowercase letters compare daytime and night-time values and uppercase letters compare temperature at different depths.

Source: The authors.

Nighttime temperature is extremely important in banana cultivation because growth occurs mainly at night. Fig. 8 shows boxplots for temperature and soil moisture at different depths. During the day, both soil temperature and moisture content decreased as depth (0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m) increased, with far fewer outliers for soil temperature.

Source: The authors.

Figure 7 Correlation between soil surface and air temperatures, for day and night periods, under three mulching scenarios (bare soil, 4 t ha-1 and 8 t ha-1 mulch covers) and at different depths (0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m).

Table 3 Mean soil moisture at depths of 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m (daytime and nighttime).

| Soil depth (m) | Soil moisture (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Night | ||

| 0.1 | 28.25 aA | 28.15 aA | |

| 0.3 | 26.40 aA | 26.43 aA | |

| 0.5 | 26.17 aA | 26.18 aA | |

Note: Means followed by the same uppercase or lowercase letter do not differ at 5% probability according to Tukey’s test. Lowercase letters compare daytime and night-time values and uppercase letters compare soil moisture at different depths.

Source: The authors

Source: The authors

Figure 8 Box plots of soil temperature and moisture content at depths of 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 m (daytime and nighttime).

Temperature fluctuates less at night, with a smaller range of 21 to 28 oC for the 3 depths studied (Fig. 8). By contrast, soil moisture content exhibited similar variation across the soil profile at night.

Soil moisture was similar across the profile, with no statistical difference between treatments. This was influenced by the drip irrigation system and the high clay content, which favor greater soil water retention (Table 3). Mulch protects the soil from the direct impact of raindrops and repeated wetting and drying cycles.

4. Conclusions

Surface temperatures were lower during the day under coconut coir dust mulch when compared to bare soil (up to a 9% reduction for 8 t ha-1).

A coconut coir mulch density of 4 t ha-1 had a significant buffer effect on soil temperature fluctuation at both the surface and up to 0.5 m.

Under mulching, both soil temperature and moisture tended to decrease with depth during the day.

Drip irrigation management associated with 4 t ha-1 of coconut coir mulch provided a uniform moisture profile close to field capacity.