Introduction

Ophidian accidents are events caused by the bite of a snake and are of public health interest worldwide. Specifically, in Central and South America, about 300 000 bites of these animals are reported each year, of which 12 000 generate sequelae and 4 000 lead to death.1 In Colombia, according to the Instituto Nacional de Salud (National Health Institute), 4 978 cases of snakebites were reported in 2017, of which 66 were caused by snakes of the genus Micrurus,2 the most diverse and representative of the family Elapidae.3-6

Snakes of the genus Micrurus, also known as coral snakes, are docile animals that do not attack humans unless provoked. These reptiles have coloration patterns that serve as a defense mechanism and repel their predators. They also possess a powerful venom with a neurotoxic effect that they only use to defend themselves7 and proteroglyph dentition, that is, their venom inoculating fang is located at the front end of the upper jaw. In this type of dentition, the groove through which the venom passes in the fang is not completely closed and, for this reason, the snake must hold onto their prey for a few seconds to ensure the entry of the venom.8

These species have a venom gland situated on each side of the head, which is made up of a main gland, a primary duct, and an accessory mucous gland. Moreover, the main gland is surrounded by branches of the pterygoid muscles and external jaw adductors.8-11

Since the production of venom in snakes is a slow process, they store it mainly in intracellular form in se-romucous cells or in the central lumen of the venom gland (to a lesser extent).8,12 In addition, the production of toxins in this gland is stimulated by biochemical and morphological changes in the secretory epithelial cells; this production process is carried out asynchronously after the extraction or inoculation of the venom, so its concentration is altered.

The amount and composition of the venom produced by snakes depends on epigenetic variations between individuals, the species, the site of origin, the ontogenetic stages, the phylogenetic changes and the feeding habits of each individual, as well as on the environmental conditions where they develop and live.10,12-16 Costa-Cardoso et al.10 state that the venom of coral snakes contains 25% total solids, 70-90% proteins and polypeptides and 10-30% low molecular weight substances such as amines, carbohydrates, amino acids, ions and inorganic compounds. Lomont et al.15 identified 22 protein families in the venom of Micrurus snakes using analytical techniques; the most abundant and representative are three-finger toxins (3FTx) and phospholipases A2 (PLA2), which contribute to the neurotoxic effect of these substances.

The proportion of PLA2 and 3FTx toxins in coral snake venoms is a key element for identifying the main neurotoxic effects of the venoms of all species of the genus Micrurus.6,9,15-17 Different researches on this subject have established that neurotoxins act through two mechanisms: on the one hand, presynaptic neurotoxins block the release of acetylcholine from the presynaptic neuron and, on the other, the postsynaptic neurotoxins competitively bind to the nicotinic receptor at the neuromuscular junction.10,18,19 Both situations lead to respiratory failure and death of the patient, if adequate treatment with antivenom is not provided timely.

The presence of these presynaptic and post-synaptic neurotoxins makes Micrurus venom lethal at low doses,20-22 making the study of the effects of this venom on the neuromuscular transmission of electrical impulses highly relevant. To this end, ex vivo preparations of striated muscle tissue and nerve are used.23,24

Based on the abovementioned, two types of tests are used to evaluate the neurotoxic and myotoxic effects of snake venom: ex vivo assessment of neurotoxicity and ex vivo assessment of myotoxicity. The neurotoxicity assessment of these venoms should be performed in both muscle and nerve preparations due to the responses of the models, as explained below.25-27

Ex vivo techniques for the assessment of neurotoxicity

The neurotoxic activity of the venom produced by Micrurus species is determined by applying a stimulus through the electrodes that are in contact with the biventer cervicis muscle of 4- to 8-day-old male chicks, or with the diaphragm and the phrenic nerve of male mice with body weight between 25g and 35g, which results in muscle contraction under normal conditions.24 To perform this analysis, electrical impulses (0.1Hz for 0.2ms) are applied using a low-frequency stimulator and muscle contractions are recorded with a force displacement transducer that is coupled to recording equipment located in the muscle tissue of an isolated organ perfusion system. After a stabilization period of 20 minutes, a single concentration (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 or 10 µg/mL) of the venom under study is added to the organ bath. To confirm the complete block of muscle contractions,8,10 and to establish the concentration of the venom that caused such an effect,27 it is necessary to apply new electrical stimuli and verify the records using a dose-response curve.

Ex vivo techniques for the assessment of myotoxicity

Using muscle preparations similar to the biventer cervix muscle of male chicks, it is also possible to evaluate the ability of the venom to induce muscle damage26

To achieve a selective stimulation of the muscle by suppressing neuromuscular activity, the preparations are placed in an organ bath in 10µM d-tubocurarine and the muscle is directly stimulated with electrical impulses of 0.1Hz at a maximum voltage of 0.2ms. The poison is then added to the preparation and left in contact until contraction is blocked or after 3 hours, after which time the tissues are immersed in 10% formaldehyde for histological examination to confirm myotoxicity.19,23,25,27

Electrophysiological alterations

Micrurus snake venom, or some of its specific toxins, can alter the transmission of the normal electrical pulse in the neuromuscular junction. This is reflected, on the one hand, in a decrease or blockage of the response to direct electrical stimulation on the muscle and, on the other, in fluctuations in resting membrane potential, such as changes in amplitude, form and frequency, and Wedensky inhibition in some cases; these effects are caused by both prolonged and short exposures to the venom or one of its toxins.24,28

Similarly, by evaluating muscle contractility after applying electrical stimulation in the presence of acetylcholine (ACh) and the venom under study, it is possible to determine if there are effects on the post-synaptic response to ACh. When there are no alterations in muscle contractility, the effect is considered presynaptic.24,25

Myotoxicity can be evaluated in an observational way and without the need for a pathological study, assessing the response of the striated muscle when exposed to the venom and the blocking action of the toxins on muscle contracture in the presence of a direct electrical impulse and high concentrations of K+ in the organ bath.26,27

Since there is new information on Micrurus snake venoms and considering the large number of this genus species in Colombia, it is necessary to encourage research that characterizes these substances biochemically and biologically and promotes the development of more specific and useful antivenins to treat snakebite accidents.

In this context, the objective of this review was to present an overview of the neurotoxicity of Micrurus snake venom and its functional characterization using ex vivo analysis methods.

Materials and methods

A literature review was conducted in the Med Line and Science Direct databases using the following search strategy: type of studies: research articles, reviewsand specialized book chapters addressing neurotoxicity of Micrurus snake venom and techniques to determine their neurotoxic activity by means of in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo models; publication period: no initial limit until June 2018; languages: English and Spanish; search terms: "Micrurus""Elapidae", "actividad neuromuscular", "neurotoxicidad", "miotoxicidad", "veneno de Micrurus","fosfolipasas A2"and "Toxinas de tres dedos", which were combined with the "AND" and "OR" connectors to establish the search equations.

The review started with the search of the basic concepts of venom, mechanisms of neurotoxicity, myotoxicity and characterization, and determination in vitro. References that made a functional characterization of the venom using ex vivo preparations of the biventer cervicis muscle of chicks or the phrenic nerve of mice were included,and those that did not meet the search criteria were excluded.

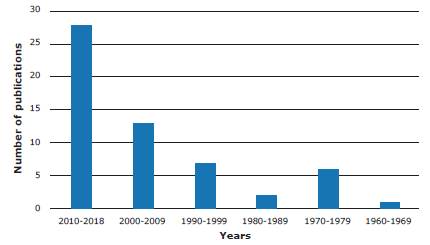

A total of 151 publications were retrieved, of which 63 were eliminated because they were duplicated; the remaining 88 were reviewed for title, abstract and methodology, and 28 were excluded because they were not relevant to the topic of interest or did not meet the selection criteria. The study also included 8 additional records (books and reports) identified through other sources and which, in the authors'opinion, complemented the information reported by the selected references; finally, 68 publications were included in the review (Figure 1).

Results

Most of the studies (n=28) included in the review were published between 2010 and 2018, with a significant increase in the number of publications since 2000 (Figure 1). Except for 3 works developed in Colombia by regulatory bodies, all the literature found was published in English.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2 Number of publications on neurotoxicity of Micrurus snake venom and methods for its analysis.

Of the 68 documents included, 16 were review articles, 5 were book chapters, 2 were guidelines and reports, and 1 was an Internet search; the remaining 44 publications were original articles and 18 of them used venoms of snakes of the genus Micrurus as samples (Table 1). Of the articles that specifically studied coral snake venom, only 6 were on Colombian species, including Micrurus dumerilii, Micrurus mipartitus, Micrurus dissoleucus, Micrurus lemniscatus, Micrurus spixii and Micrurus surinamensis, that is, only about 16% of the snake venoms of the genus Micrurus found in the country have been studied. Out of these species, only the proteome of the venom of M. dumerilii and M. mipartitus have been characterized16,21,29 since they are the main varieties involved in snakebites.

One of the studies found19 assessed the neurotoxic activity of the venom of M. mipartitus and M. dissoleucus by means of isolated muscle preparations and established the functional characterization of each one. Another study20 described the multiple enzymatic activities of the venom of M. lemniscatus, M. spixii and M. surinamensis and evaluated the toxicity of each venom on different prey animals.

The study developed by Rey-Suarez et al.29 showed that the venom proteome of the species M. mipartitus found in Colombia has a higher proportion of 3FTx, which is a different phenotype from that of the venom of M. dumerilii, a species that has higher levels of PLA2.16,21 Moreover, the study by Renjifo et al.19 found that the venom of M. mipartitus species has post-synaptic activity associated with the inhibition of muscle contraction caused by the presence of ACh, which is related to the large amount of 3FTx.

The use of ex vivo models for the assessment of snake venom neurotoxicity began with studies on elapid species, especially in the Old World, as evidenced in 7 of the articles included in the review.24,26,28,30-33 Table 1 contains the studies found that were conducted on snakes of the genus Micrurus, as well as the articles that assessed neurotoxic activity of elapid venoms.

Discussion

Although the number of publications on snake venoms of the genus Micrurus has increased worldwide since 2007, studies in Colombia are still scarce. This increase in research may be explained by the development of proteomic techniques that allow analyzing the protein composition of venoms; thus, techniques such as re-versed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, electrophoresis and mass spectrometry have been used to identify the proteins present in venoms and determine their relative abundance and sequencing.32,44-46 However, it should be noted that this type of study may have limitations in terms of accessibility, cost and operation of some of the equipment used.

The neurotoxicity of coral snake venom is associated with PLA2 and 3FTX, which lead to flaccid paralysis of the respiratory muscles. For this reason, the development of neurotoxicity models that allow verifying the influence of full venom and these toxins on the synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction can be key for its functional characterization, as it has been evidenced in studies developed with elapid venoms of the genus Bungarus,,28,30,31,47Oxyuranus,,24,30,31,34,48Pseudonaja,23,33 and Notechis.49

The following are the findings on Micrurus snake venom, its neurotoxicity, and its effects on the neuro-muscular junction.

Mechanism of action of PLA2 and 3FTx

The venom of snakes from the genus Micrurus has neurotoxic components. Lomonte et al.15 identified the following families of proteins in its proteome: 3FTx (a-neurotoxins), PLA2 (P-neurotoxins), metalloproteases, L-amino-acid oxidases, Kunitz-type serine protease, C-type lectin-like proteins, acetylcholinesterase and hyaluronidases, being the first two the ones with more involvement. The proportion of PLA2 and 3FTx toxins in these venoms is a key element for identifying their main neurotoxic and myotoxic effects.15,16,18

Table 2 presents some of the neurotoxins identified in snakes of the family Elapidae. It also includes the characteristics of the snake venom of the genus Crotalus durissus due to its neurotoxic and myotoxic behavior.22

Table 2 Neurotoxins identified in snake venom.

| Species | Toxin | Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notechis scutaus | Notexin | β-neurotoxins | 49 |

| Oxyuranus scutellatus | Taipoxin | β-neurotoxins | 30,31,48 |

| Oxyuranus microlepidotus | Paradoxin | β-neurotoxins | 34,50 |

| Crotalus durissus terrificus | Crotoxin | β-neurotoxins | 28,30,31,51,52 |

| Pseudonaja textiles | Textilotoxin | β-neurotoxins | 23,33 |

| Bungarus multicinctus | β-bungarotoxin | β-neurotoxins | 28,31 |

| Micrurus frontalis | Frontoxin | α-neurotoxins- 3FTX | 35 |

| Micrurus lemniscatus | Lemnitoxin | β-neurotoxins | 42 |

| Micrurus dumerilli | MdumPLA2 | β-neurotoxins | 16 |

| Micrurus mipartitus | MmipPLA2 | β-neurotoxins | 16 |

Source: Elaborated based on Hodgson & Wickramaratna.23

Recent studies in proteomics have demonstrated the predominance of PLA2 and 3FTx toxins in the venom phenotype in species of the genus Micrurus and have shown that their proportions vary widely across the American continent.14,16,21,22,41-43 Similarly, Lomonte et al.15 made a projection of the behavior of these two toxins, finding that PLA2 is more abundant in the southern cone and that 3FTx predominates in Central and North America. However, it is worth mentioning that this projection should be corroborated by a detailed analysis of each of the venoms since the evolutionary and ecological processes of each species are factors that determine the greater proportion of one of these 2 toxins.

PLA2 toxins

PLA2 is a superfamily of enzymes composed of 16 groups that are classified according to their type into: secreted PLA2 (sPLA2), cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), platelet activating factor (PAF), lipoprotein-associated PLA2 (LpPLA2s), adipose PLA2 (AdPLA2s) and lysosomal PLA2 (LPLA2s). The first two are especially important because they are involved in the inflammatory and degenerative response of the central nervous system.53 sPLA2 are present in different classes of venoms and are classified in four main subtypes, and types 1 and 2 are found in snake venoms, mainly in elapids, vipers and crotalids; these enzymes are single-chain polypeptides and have a molecular mass of 13-15 kDa, with approximately 7 disulfide bonds. Finally, cPLA2 has a molecular mass of 40-100 kDa and depends on calcium for functioning.53

Even though the exact neurotoxic route of PLA2 is not known, at least three mechanisms of action by which these enzymes exert their presynaptic toxic activity have been described: 1) the neurotoxin induces phospholipid hydrolysis of the presynaptic membrane and prevents it from interacting with the acetylcholine vesicles, 2) the damage described in the cell membranes favors the excessive influence of Ca++ inside the cells, which causes an exaggerated release of the acetylcholine neurotransmitter, as well as the alteration of its recycling process and its subsequent depletion, and 3) its enzymatic activity is left aside, so the protein complexes that favor the coupling of the vesicle and the presynaptic membrane are blocked.16,23,47,54-56

3FTx toxins

3FTx are non-enzymatic polypeptide structures made up of between 60 and 74 amino acid residues that are among the main components of elapid venoms.57 Its structure has 3 loops of p-sheets that extend from a small globular hydrophobic core that is linked by 4 preserved disulfide bonds; this structure resembles that of a hand with 3 fingers, which is why they are known as three-finger toxins.57,58

Neurotoxicity (main effect of coral snake venom), cytotoxicity and cardiotoxicity are some of the pharmacological effects identified in 3FTx. However, it should be noted that its biological activity varies depending on the affinity it has with the receptors59-61 (Table 3).

Table 3 Three-finger toxins found in elapid venoms.

| 3FTx type | Mechanism of action | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotoxins | α | α 1 and/or α 7 nAChR antagonists. | α-bungarotoxins |

| K | They recognize different subtypes of neuronal α 3β4 nAChR | K-bungarotoxins | |

| MT | They selectively bind to mAChR. | Dendroaspis angusticeps MT1 | |

| Cardiotoxins | They form ionic pores in lipid membranes. | Cardiotoxin V4II from Naja mossambica | |

| α -cardiotoxins and others alike | They bind to β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors. | CTX9, CTX14, CTX15, CTX21 and CTX23 from Ophiophagus Hannah | |

| Non-conventional | Weak neurotoxins with nanomolar affinity to AChR α1 (reversible binding) and α7 (poorly reversible binding) | Candoxin | |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | They bind to acetylcholinesterase | Fasciculins | |

| L-type Ca2+ channel blockers | They block L-type Ca2+ channel in skeletal and heart muscles | Calciseptine | |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | They interfere with the interaction between fibrinogen and the glycoprotein IIB-IIIa receptor (αIIBβ3). | Dendroaspins | |

nAChR: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; mAChR: muscarinic acetylcholine receptors; MT: muscarinic toxin; CTX: cardiotoxin

Source: Elaboration based on Utkin59, Kini & Doley60 and Nirthanan et al.61

Depending on the amino acid sequence, 3FTx neurotoxins can be classified into two types: short-chain neurotoxins (type I) and long-chain neurotoxins (type II), both with a molecular mass varying between 6 and 9 kDa.58,61 Short-chain a-neurotoxins are the main responsible for the neurotoxic effect of elapid venoms due to their high- affinity binding for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and the inhibitory control they exert on this receptor without affecting the release of neurotransmitters from the presynaptic terminal.59,62,63

Functional characterization of the neurotoxic activity of venoms of the Elapidae family and the Micrurus genus in particular

Recent studies on the classical biochemistry of elapid venom composition in Colombia have made major progress in the description of the ontogenetic characteristics and phylogenetic trees of these species.16,19,21 In this regard, multiple research works assess the peripheral neurotoxic and myotoxic activity of the venom of M. dissoleucus, M. mipartitus,19M. lemniscatus, Micrurus frontalis and M. surinamensis,13 or the PLA2 of the species Micrurus nigrocinctus.64

Specifically, for Australian elapids (Pseudechis spp.), Hart et al.65 indicated that binding of neurotoxins to nAChR is more effective in preparation from chick muscle than in human and rat skeletal muscles. This difference is explained because the synaptic junctions are almost absent in birds, even though neuromuscular junctions in avian tissues are almost the same size as in rats; this makes nAChR more susceptible to post-synaptic neurotoxins and more sensitive to the neurotoxic action of elapid venoms.65

Although the neurotoxic activity of Micrurus snake venom has not been sufficiently studied, several methodologies have been used as complementary techniques besides organ baths, e.g. cell culture models, that can contribute to the understanding of the actions of the full venom and its main components (PLA2 and 3FTx). For example, hippocampal tissue has been used to prove viability and conservation of cellular function (integrity of mitochondria and intracellular calcium variability) after the administration of different doses of venom from these species,66 to establish toxin binding to transmembrane receptors,67 and determine electroencephalographic and neuropathological changes in behavioral studies of animal models.68

Conclusions

Advances in venomics, the global study of venom through omic techniques, allow for a better understanding of the protein constituents of snake venoms. In the specific case of the genus Micrurus, such advances are of vital importance due to the small amount of venom produced by these species and the limitations of having them in captivity. Furthermore, the identification of proteins with neurotoxic properties such as a-neurotoxins and p-neurotoxins, main components of Micrurus venom, and the understanding of their mechanism of action in ex vivo muscle tissue preparations, are fundamental tools for the development of toxinology and allows understanding the mechanism of action of these components and the great protein variability of each species and each individual.

Establishing the characteristics of snake venom proteomes has potential benefits for basic research on these substances, such as the identification of new molecules in the venom. This also contributes to a better understanding of the evolution and biological effects that these venoms can have. Likewise, this characterization is useful for the clinical diagnosis of snakebites and for the development of new research tools and drugs with clinical potential as specific antivenoms.

Studies with ex vivo muscle and nerve preparations to assess the effect of neurotoxins are a good model to characterize the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic effect of Micrurus snake venom. Moreover, these preparations serve as a support for muscle tissue histopathology to determine myotoxicity resulting from exposure to poison.