Introduction

Anisakidosis is a parasitic disease that affects humans. Although most patients are asymptomatic, it can cause gastrointestinal symptoms and allergic or gastroallergic reactions.1 This infection occurs when third-stage larvae (L3) of parasitic nematodes of the family Anisakidae are ingested through raw or undercooked fish or cephalopods.2

According to Jofré et al.,3 the term anisakidosis was introduced by Straub in 1960, the same year in which Van Thiel and colleagues reported the first case of this disease in the Netherlands.

The symptoms of anisakidosis are explained by two pathophysiological mechanisms: an immediate hypersensitivity reaction and an inflammatory reaction.4 Therefore, as mentioned above, symptoms may range from allergic reactions to gastrointestinal manifestations. This infection, which is more frequently observed in adults, is usually caused by a single larva, although there are case reports of more than one larva.4

Some of the species associated with anisakidosis are Anisakis simplex, Anisakisphyseteris and Pseudoterova decipiens, as well as the genus Hysterothylacium.3,5,6 To diagnose this disease, the symptoms of the patients and their history of consumption of raw or undercooked fish or cephalopods must be reviewed. In the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, it is necessary to detect and identify the larvae, either in vivo by endoscopy or in situ with a biopsy.4 Depending on the location of the larva, anisakidosis may be gastric, intestinal, or extraintestinal (lung, liver, and pancreas).7

On the other hand, in the presence of allergic symptoms, it is not necessary to directly visualize the larva since the symptoms are mainly attributed to the immune response of the host and the diagnosis is usually made using serological tests.1 It should be noted that when the result of these tests is positive, a cross-reaction with other ascarids should be ruled out.8 The allergic and gastroallergic forms are characterized by urticaria, angioedema or anaphylaxis, along with digestive symptoms.9,10

In Europe and Asia, more than 2 000 cases of anisakidosis are reported each year; for this reason, as stated by Audícana et al. ,11 authorities have extensively studied the disease and have established rules for its control and prevention. On the contrary, in South America, despite having a large fishery industry, anisakidosis is not a common disease and, therefore, its clinical manifestations are little known by the healthcare staff. This creates difficulties with the diagnosis and could lead to underreporting of the disease.12 Likewise, the information available in the region about this disease is mostly found in some research papers and in a few case reports published in specialized journals,13-15 but there is no updated review of the subject.

Consequently, the objective of this review was to describe intermediate hosts and identify case reports of anisakidosis published in South America, with a focus on the major marine fish species that could be involved in their transmission, given that this infection is considered a potential emerging disease in the region that needs to be known, studied, and treated.

Materials and methods

A systematic review was conducted to answer two questions: What are the clinical cases of anisakidosis reported in South America? and What are the fish species reported as hosts of anisakid nematodes in South America?

Eligibility criteria

Case reports and cross-sectional observational studies were included in the search. Inclusion criteria for case reports on anisakidosis were that one or more larvae of the family Anisakidae had been identified in the patients that had a history of fish consumption likely to be parasitized by nematode larvae from this family and that came from any South American country.

Also, to identify the hosts, studies reporting cases of fish for human consumption parasitized by nematodes of the family Anisakidae and captured in South American waters were included. Studies that did not have the information required to determine their eligibility and whose authors did not respond to the request for such data were excluded.

Search strategy

A structured search using MeSH and DeCS terms was performed in Medline, Cochrane, Embase, LILACS and Scopus databases based on the following search strategy: publication period: from the inception of each database until September 2018; languages: English, Spanish and Portuguese; type of studies: case reports and cross-sectional observational studies; search terms: "Anisakids", "Anisakiasis", "Anisakidosis", "Anisakidae", "Anisakis", "Pseudoterranova" and "Contracecum", which were combined with each of the South American country names (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay and Venezuela).

The following is the search equation was used in MEDLINE and Cochrane (tiab means Title/Abstract): ((((anisakis [tiab] OR pseudoterrova [tiab] OR anisakidae [tiab] OR Anisakiosis [tiab] OR ANISAKIASIS [tiab] OR) AND (Argentina [tiab] OR BOLIVIA [tiab] OR BRAZIL [tiab] OR CHILE [tiab] OR COLOMBIA [tiab] OR ECUADOR [tiab] OR FRENCH GUIANA [tiab] OR GUYANA [tiab] OR PARAGUAY [tiab] OR PERU [tiab] OR Suriname [tiab] OR Uruguay [tiab] OR Venezuela [tiab] OR)) OR (("South America"[Mesh]) AND "Anisakis"[Mesh]).

The database search was complemented by an unstructured search in SciELO and Google Scholar and with additional studies recommended by experts in the field. Similarly, the reference lists of the included narrative reviews were assessed to identify publications potentially relevant to the objective of the study, which were also included in the analysis.

The prevalence of infection in articles reporting unspecified hosts was calculated as the ratio between the number of fish parasitized by species of the family Anisakidae and the number of fish reviewed, if available.

Results

The initial search yielded 166 results (140 from the databases and 26 from SciELO, Google Scholar and expert recommendations), of which 73 were excluded because they were duplicates, 4 because they were incomplete and 26 because they did not meet the in clusion criteria. Subsequently, the reference lists of the 63 publications found were assessed and 6 additional articles were identified, resulting in a total of 69 publications to be included in the review: 16 case reports, 3 seroprevalence studies, and 50 host records (Figure 1). The characteristics of the selected articles are described in Table 1.

Table 1 General characteristics of articles selected for review.

| Authors Year | Place of publication | Type of publication | Human/ Host | Sample size (n) | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figueiredo et al. 2013 | Brazil | RA | Humans | 67 | Positive anti-Anisakis simplex immunoglobulin E response |

| Jofré et al.3 2008 | Chile | CR | Humans | 1 | Infection with Pseudoterrova decipiens after the ingestion of sushi |

| Castellanos et al.12 2017 | Colombia | RA | Hosts | 15 | Presence of anisakid nematode larvae parasitizing Mugil cephalus |

| Cabrera & Suárez- Ognio13 2002 | Peru | C | Hosts | 2 | Two probable cases of anisakidosis |

| Humans | 12 | Presence of Anisakis larvae in Coryphaena hippurus | |||

| Cabrera & Trillo- Altamirano14 2004 | Peru | SpC | Humans | 1 | Probable case of infection by a L4 P. decipiens larvae |

| Mercado et al.15 2001 | Brazil | SC | Humans | 7 | Identification of seven cases of infection by L4 P. decipiens larvae |

| Torres et al.16 2007 | Chile | RN | Humans | 4 | Outbreak of pseudoterranovosis in three out of four people who shared the same dish of raw fish (ceviche) |

| Weitzel et al.17 2015 | Chile | LE | Humans | 3 | Report of three cases of infection with Pseudoterranova cattani |

| Mercado et al.18 2006 | Chile | CLC | Humans | 1 | Patient infected with a L4 Pseudoterranova sp. larva |

| Menghi et al.19 2011 | Argentina | CLC | Humans | 1 | Larva of the Anisakis-Contraecum complex in the stool of a girl |

| Mayo-Iniguez et al.20 2014 | Argentina | SC | Hosts | 15 | Molecular diagnosis of Anisakis typica and Anisakisphyseteris in larvae of hosts of the Brazilian coast |

| Timi et al.21 2014 | Argentina | RA | Hosts | 34 | Molecular diagnosis of P. cattani in fish from Argentine waters |

| Wadnipar-Cano22 2014 | Colombia | T | Hosts | 360 | Parasitic infestation by anisakid nematodes in river fish in the municipality of San Marcos, Colombia. |

| Dias et al.23 2010 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 100 | Parasitation by Anisakis spp. and Contraecum sp. of Aluterus monoceros purchased in markets of the municipalities of Niteroi and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Cabrera et al.24 2003 | Peru | PR | Humans | 1 | Case of human anisakidosis due to L3 P. decipiens larva. |

| Tanteleán & Huiza25 1993 | Peru | PR | Humans | 2 | P. decipiens larvae obtained from the mouth of two people in Lima, Peru |

| Barriga et al.26 1999 | Peru | PR | Humans | 1 | Extraction of larvae by endoscopy, subsequently identified as Anisakis spp., in a patient from Lima, Peru |

| Rosa-da Cruz et al.27 2010 | Brazil | SC | Humans | 1 | First evidence of larvae similar to Anisakis spp. causing gastrointestinal lesions in Brazil |

| Patiño & Olivera28 2019 | Colombia | CP | Humans | 1 | First case of anisakiasis in Colombia |

| Puccio et al.29 2008 | Venezuela | OA | Humans | 144 | Report of a high percentage (45%) of children with positive skin tests for A. simplex extract |

| Verhamme & Ramboer30 1988 | Chile | CR | Humans | 6 | Case compatible with gastrointestinal anisakidosis after eating salmon in Chile |

| Torres et al.31 2000 | Chile | CR | Humans | 1 | Elimination of L2 anisakid larvae in a man from Santiago de Chile who had previously eaten shellfish and raw fish. |

| Mercado et al.32 1997 | Chile | N | Humans | 1 | Extraction of L4 P. decipiens larva during gastrointestinal biopsy of the stomach in a man from southern Chile |

| Figueiredo et al.33 2015 | Brazil | OA | Humans | 309 | Reactivity to anti-Anisakis in pregnant mothers in Brazil |

| Mancini et al.34 2014 | Argentina | OA | Hosts | 1402 | Identification of Contraecum sp. larvae compatible with type 2 L3 larvae in 9 fish species from 19 aquatic environments in Argentina |

| Ulloa-Ulloa & Carrasco-Mancero35 2008 | Colombia | T | Hosts | 167 | Identification of three fish species from Ecuador parasitized by Contracecum sp. |

| Oliverero-Verbel & Baldiris-Avila36 2008 | Colombia | B | Hosts | Unknown | Identification of multiple species of fish parasitized by nematodes the family Anisakidae in Colombia |

| Hernández-Orts et al.37 2013 | Argentina | RA | Hosts | 542 | Identification of Pseudoterranova sp. larvae and molecular identification of P. cattani in 12 fish species from Patagonia, Argentina. |

| Castellanos et al.38 2018 | Ecuador. | OA | Hosts | 438 | Identification by taxonomic revision of 8 species of host fish of the genera Anisakis sp. and Pseudoterranova sp. from Ecuador and Colombia |

| Colombia | |||||

| Luque & Alves39 2001 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 115 | Identification of anisakid nematodes in two fish species from Brazil |

| Knoff et al.40 2001 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 217 | Identification of multiple genera of the family Anisakidae parasitizing elasmobranch fish in Brazil. |

| Rodrigues41 2010 | Brazil | T | Hosts | 52 | Presence of anisakids in a fish species marketed in Brazil |

| Timi et al.42 2000 | Argentina Uruguay | OA | Hosts | 2086 | Identification of four species of anisakid nematode larvae in a fish species from Argentine and Uruguayan waters. |

| Chavez et al.43 2007 | Chile | CP | Hosts | 300 | Larvae of Anisakis sp. nematodes found in samples of a fish species obtained in two localities in Chile |

| Bracho-Espinoza et al.44 2013 | Venezuela | OA | Hosts | 180 | Identification of anisakids in three species of fish from Venezuela |

| Marigo et al.45 2015 | Brazil | CR | Hosts | 1 | Identification of Pseudoterranova azarasi in cod sold for human consumption in Brazil |

| de Paula Toledo Prado & Capuano46 2006 | Brazil | SC | Hosts | 11 | Presence of nematodes larvae of the family Anisakidae in cod samples from a Brazilian locality |

| Torres et al.47 2014 | Chile | OA | Hosts | 280 | Identification of Pseudoterranova sp. in Thyrsites atun from Chile, and of other anisakid larvae in two other fish species. |

| Di Azevedo & Iñiguez48 2018 | Brazil | RA | Hosts | 180 | Molecular identification of Hysterothylacium dearddorffoverstreetorum (s.l) in three fish species from Brazil. |

| Pardo et al.49 2007 | Colombia | OA | Hosts | 45 | Identification of Salminus affinis fish from the Sinú and San Jorge rivers parasitized by Contracecum sp. anisakids |

| Knoff et al.50 2013 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 87 | Collection of anisakid in larval stages in Lophiusgastrophysus specimens from Brazil |

| Torres-Frenzel51 2013 | Chile | T | Hosts | 78 | Isolation of L3 anisakid Pseudoterranova sp. nematodes in ceviche servings in Chilean restaurants |

| Torres et al.52 1993 | Chile | RN | Hosts | 57 | Identification of nematode larvae of the family Anisakidae in five fish species in southern Chile |

| Vicente et al.53 1989 | Venezuela | OA | Hosts | 136 | Presence of Contracecum sp. (s.l) in Micropogonias furnieri from Venezuela |

| Fernández et al.54 2016 | Chile | BC | Host | 1 | Identification of larval forms of Anisakis sp. (Type I, L3) in the intestinal serosa of ocean sunfish from Chile |

| Olivero-Verbel et al.55 2005 | Colombia | OA | Hosts | 386 | Presence of L3 larvae of the family Anisakidae in mugilids from two locations on the Colombian Atlantic Coast |

| Soares et al.56 2018 | Argentina Brazil | OA | Hosts | 186 | Identification of anisakid genus in a fish species from Argentine and Uruguayan waters. |

| Saad & Luque57 2009 | Brazil | RN | Hosts | 36 | Collection of Anisakis sp. and Contraecum sp. larvae in fish from the coastal zone of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Soares et al.58 2014 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 100 | Presence of Pseudoterranova sp. larvae in fish from the coast of Cabo Frio, Brazil |

| Paraguassú et al.59 2002 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 90 | Collection of parasites of the family Anisakidae in fish from the Brazilian coast |

| Farias-Rabelo et al.60 2017 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 25 | Identification of fish infested with L3 larvae of the family Anisakidae in Brazil |

| Braicovich & Timi61 2008 | Argentina Uruguay | OA | Hosts | 177 | Presence of three genera of the family Anisakidae in fish caught in fishing waters located between Argentina and Uruguay |

| Pantoja et al.62 2015 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 50 | Molecular identification of A. typica and Hysterothylacium sp. larvae in two fish species from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Kuraiem et al.63 2016 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 30 | Identification of species marketed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, parasitized by Anisakis sp. and Hysterothylacium deardorfoverstreetorum larvae |

| Timi & Lanfranchi64 2009 | Argentina | RA | Hosts | 100 | Identification of larvae of the family Anisakidae in a species of fish inhabiting the Argentine sea |

| Ramallo & Torres65 1995 | Argentina | OA | Hosts | 10 | Isolation and morphological identification of Contraecum sp. in a fish species from the of Rio Hondo pond, Argentina |

| González et al.66 2006 | Argentina Chile Peru | OA | Hosts | 626 | Presence of endoparasites of the genus Anisakis sp. in a species of fish present on the Pacific Coast of South America |

| Hamann67 1999 | Argentina | OA | Hosts | 237 | Finding of fish from northeastern Argentina parasitized by Contracecum sp. larvae |

| Mattiucci et al.68 2002 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 6 | Detection of A. typica in multiple fish on the Atlantic Coast of Brazil |

| Peña-Rehbein et al.69 2012 | Chile | RN | Hosts | 20 | Description of the frequency and number of Anisakis spp. nematodes in the internal organs of T. atun fish from Queule, Brazil |

| Oliva70 1999 | Chile Peru | OA | Hosts | 3034 | Identification of anisakid nematodes in a fish species whose specimens were captured in Chile and Peru. |

| Novo-Borges et al.71 2012 | Brazil | RA | Hosts | 64 | Morphological and molecular identification of A. typica and Hysterothylacium sp. larvae in two fish species from Brazil |

| Braicovich et al.72 2017 | Argentina Brazil | RA | Hosts | 488 | Identification of larvae of the family Anisakidae in fish from the coastal region of South America between Rio de Janeiro and northern Argentina |

| Andrade-Porto et al.73 2015 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 100 | Identification of Arapaima gigas parasitized by L3 larvae of Hysterothylacium sp. |

| Torres et al.74 1998 | Chile | OA | Hosts | 80 | Identification of Hysterothylacium geschei larvae in fish from Brazil |

| Maniscalchi Badaoui et al.75 2015 | Venezuela | OA | Hosts | 913 | Identification of fresh fish of popular consumption in Venezuela parasitized by anisakid nematodes |

| Ruiz & Vallejo76 2013 | Colombia | OA | Hosts | 378 | Identification of Contracecum sp. and Pseudoterrova sp. nematode larvae in Mugil cephalus from the Colombian Caribbean |

| Bicudo et al.77 2005 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 80 | Identification of larvae of anisakid nematodes, Anisakis sp. and Hysterothylacium sp. in fish from the coastal zone of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Knoff et al.78 2012 | Brazil | OA | Hosts | 60 | Characterization of larvae in fish from the state of Rio de Janeiro as H. deardorffoverstreetorum sp. nov. larvae |

RA: research article; CR: case report; C: communication; SpC: special contribution; SC: short communication; RN: research note; LE: letter to editor; CLC: clinical case; T: thesis; OA: original article; CP: case presentation; N: notes and information; B: book; CA: conference article; BC: brief communication.

Source: Own elaboration.

Clinical cases of anisakidosis in South America

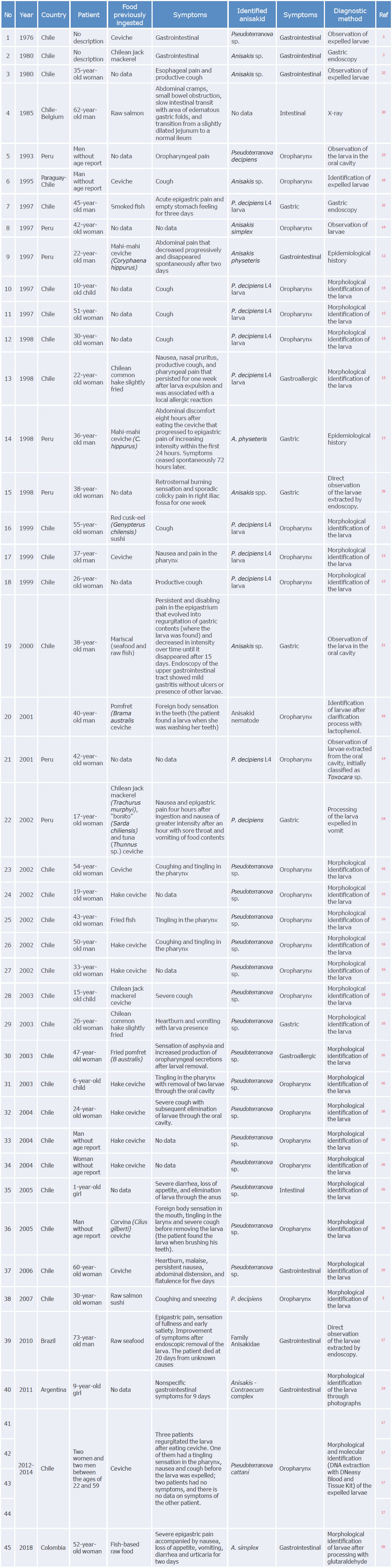

In Europe and Asia, anisakidosis is considered a public health issue due to the large number of cases reported with gastric, allergic and gastroallergic symptoms; however, in South America, it is still a little-known disease. Table 2 presents a summary of clinical cases associated with anisakid parasites in South America published between 1976 and 2018.

Intermediate fish hosts of anisakids reported in South America

Anisakid nematodes are parasites present in marine mammals and fish species for human consumption. For example, in South America, fish parasitized by these species have been identified in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Table 3 lists the fish species identified as hosts of parasites of the family Anisakidae in the region.

Table 3 List of secondary fish hosts of Anisakidae parasites in South American countries.

ND: no data.

Source: Own elaboration.

The present systematic review also made it possible to establish, for the first time, the geographic distribution of the different species of anisakid nematodes reported in fish marketed in South America (Figure 2).

Discussion

The presence of nematodes of the family Anisakidae in fish for human consumption in South American countries, both in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, is significant. However, cases of anisakidosis reported in humans are few and mostly localized in Chile and Peru, leading to the idea that this infection is present in the region and may be a probable zoonosis that is not being detected due to a lack of awareness among healthcare professionals.

The recent increase in the availability of Mediterranean and Eastern dishes made from raw or undercooked fish and cephalopods in South America has increased the risk of infection and hence the number of cases of anisakidosis. This may also explain why most of the known cases in the region are found in Chile and Peru, countries where the gastronomic culture involves the consumption of marinated or salted seafood, mainly ceviche.

According to the findings of the present study, it is noteworthy that the genera Anisakis and Pseudoterranova were identified in the registry of parasitized fish for consumption since they are the parasites with the greatest impact on human health in countries where anisakidosis is highly prevalent, such as Spain and Japan;11 however, this is not reflected in the clinical cases described.

Similarly, this registry included fish parasitized by the genera Contracaecum and Hysterothylacium, of which, at the time of writing this review, no infections had been reported in humans in South America. In contrast, there have been case reports of infection with Hysterothylacium aduncum (two in South Korea and two in Japan) and Contracecum osculatum (one in Japan) from across the world,7 indicating either a possible emerging disease or a severe underreporting of this infection in the region.

Reports of anisakidosis in South America are relatively new, except for the first case reported in Chile in 1976, according to Jofré et al. ,3as they were published in the last 25 years. Moreover, in the region, there is evidence of an increase in the registration of cases between 1997 and 2005, followed by a large number of studies, of which the most recent was published in 2018. 28

As mentioned above, most cases of anisakidosis were found in Chile (n=35)3,13,18-23 and Peru (n=8),13,14,24-26 where consumption of raw fish in the form of ceviche is common in coastal areas. However, due to the long periods between cases, healthcare personnel may not issue a disease warning if they are considered rare cases. In addition, in Brazil, Argentina and Colombia, only one report was found in each country.19,27,28

It should be noted that the report made public in Colombia was based on studies conducted by Castellanos et al.,38 Castellanos-Garzón79 and Castellanos et al.,80 all published in 2018, who identified for the first time the presence of A. physeteris and P. decipiens in fish for human consumption marketed in the country, specifically in the port of Buenaventura. As a result, a warning about the possibility of anisakidosis being an emerging disease was released.

Gastrointestinal anisakidosis was the most frequent in South America, with a total of 45 cases.3.13-19.24-28.30-32 The oropharyngeal, gastric, intestinal and gastrointestinal presentations were also observed, the oropharyngeal being the most common with 29 cases. In addition, 4 asymptomatic cases with expulsion of larvae through the oral cavity were found, as well as 12 cases with clinical symptoms that varied depending on the section of the gastrointestinal tract affected by the larvae; regarding the latter, cough, pain and tingling in the pharynx, acute epigastric pain (pyrosis), nausea and abdominal cramps were the most frequent symptoms. In general, patients' condition improved in the following 36 hours to 15 days after ingestion.

In 41 (91.1%) cases of gastrointestinal anisakidosis, the infection was caused by a single larva in the late stages (L3 and L4), which was identified taxonomically. At this point it is important to note that diagnosing anisakidosis can be problematic because larval identification only allows for genus identification, and species can only be determined morphologically in adult parasites found in marine mammals. Molecular biology techniques that are costly and not available in the region are required to identify the larval stage of the species.

Despite the above, Weitzel et al.,17 using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit molecular diagnostic technique, identified Pseudoterranova cattani as the causal agent of gastrointestinal anisakidosis in the oropharyngeal form in five patients from Chile. Furthermore, Castellanos et al.38 described the species A. physeteris and P. decipiens in fish from the Pacific Ocean in Colombia and Ecuador using molecular biology and the multiplex PCR technique.

Similarly, three studies were found in the literature, two from Brazil and one from Venezuela, in which an allergic response to A. simplex allergens was reported. 1,29,33 This is evidence that people who have come into contact with Anisakis spp. and have formed antibodies against it are present in the region and are more likely to have an allergic reaction, and even an anaphylactic response, in a posterior contact through a type I hypersensitivity reaction.

Based on the information obtained from the clinical case reports, it was established that 95 species of anisakid intermediate fish hosts have been reported in South America, which should be studied in depth as they are the direct source of infection in humans. These species were found in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela11-13 15,19-22,33-77, as described below.

In Argentina, 22 species of fish for human consumption were identified. They were parasitized with species of the genera Contracaecum, Pseudoterranova, and Hysterothylacium and the species Hysterothylacium aducum, A. simplex and P. cattani, with a variable prevalence of up to 100% in several hosts.34,37,56

The largest number of host fish species was identified in Brazil, 34 in total, which were parasitized by A. typica, A. physeteris, A. simplex, P. azarasi, Contracaecum sp., Anisakis sp., Pseudoterranova sp., Hysterothylacium sp., H. fortalezae and H. deardorffoverstreetorum20,23,39-41,45,46,48,50,56-60,62,63,68,71-73,77,78

In Chile, 15 hosts were identified and there were reports of infection with the genera Anisakis, Pseudoterova and Hysterothylacium and their species A. simplex, A. physeteris, P. decipiens and H. geschei.43,47,51,52,54,66,69,70,74

In Colombia, reports were found for 17 host species, including marine and inland water fish, in which the presence of the genera Anisakis, Pseudoterranova and Contracaecum and the species A. physeteris and P. decipiens was established by taxonomic identification 12,22,36,38,49,55,76

In Ecuador, 8 host fish species were identified: Ulloa-Ulloa & Carrasco38 reported the presence of Contracaecum sp. in flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus), "trahira" (Hoplias microlepis), "bagre pintado" (Hexanematichthy sp.) and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), while Castellanos et al.,38 in a study carried out on the country's Pacific coast, identified the species A. physeteris and A. pegreffi in hake (Merluccius gayi); these authors also compiled other reports of infection by A. physeteris in bullet tuna (Auxis rochei), "bonito" (Katsuwonus pelamis) and "dorado" (Coryphaena hippurus).

In Peru, which was the country with the second highest number of reports of clinical cases of anisakidosis, 7 species of anisakid fish hosts were identified. Anisakis sp, A. physeteris, P. decipiens, A. simplex, Pseudoter-ranova sp., Contracaecum sp. and Hysterothylacium sp. were isolated.13,14,70

In Venezuela, Vicente et al.,53 Bracho-Espinosa et al.44 and Maniscalchi-Badaoui et al.75 reported that two species of fish of the family Mugilidae were hosts of the genera Anisakis, Pseudoterranova and Contracaecum. In addition, reports of infestation by Contracaecum sp. and Pseudoterranova sp. in the fish Eugerres plumieri and Micropogonias furnier were found in this country.44,53,75

Finally, in Uruguay, only two hosts with infection by A. simplex, Contracaecum sp., Hysterothylacium sp. and Pseudoterranova sp. were reported.42,61

Mullets, especially those of the species M. cephalus, rank first among all fish reported to have been infected by nematodes of the family Anisakidae, with a prevalence of infection of up to 100%. The high percentage of parasitization in mullets can be attributed to their geographical distribution, as they are found in both Atlantic and Pacific coastal waters, being species of economic and commercial importance.

Among the species with a high number of reports are also Brazilian flathead, which was parasitized by Hysterothylacium sp. (74.01%), A. simplex(51.41%), P. cattani (25%) and Contracaecum sp. (6.74%) and Hoplias malabaricus, which were all parasitized by Contraecum sp. A remarkable finding was that in about 45% (n=43) of the hosts, multiple infection by two or more species of parasites of the family Anisakidae was reported.

Based on the above, it is possible to establish that legislation on handling, processing, early evisceration and freezing at standard temperatures (-20°C) of fish is necessary in South America to adequately control the number of infected animals and thus prevent anisakidosis. At the same time, the study of this infectious disease should be promoted in healthcare institutions, with a focus on disease prevention and early management to effectively monitor the emergence of new cases and reduce underreporting.

Conclusions

The present review established the current panorama of the reported intermediate hosts for anisakids and clinical case reports of anisakidosis in South America. It was determined that this infectious disease is a latent risk for the region, so it is necessary to establish effective regulations to control its occurrence and provide more information to the general population on the necessary precautions regarding the consumption of saltwater fish.