Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), also known as neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, is a rare and aggressive neuroendocrine neoplasm of the skin1-3that was first described in 1972 by Toker as a trabecular cancer of the skin.4 Despite being 40 times less common than malignant melanoma, MCC has twice its fatality rate.5-7

The incidence rate of MCC varies between 0.13 and 1.6 cases per 100 000 inhabitants; moreover, in the United States and Europe it has increased in recent years, with an average of 0.18-0.41 cases per 100 000 inhabitants.4,5,8 Australia is the country with the highest number of MCC cases, with an annual rate of 1.6 cases per 100 000 inhabitants,8-10 whereas in Cuba there are few reports of this type of neoplasm.

Risk factors for MCC include exposure to ultraviolet light, immunosuppression, advanced age, and polyomavirus infection.11,12 These neoplasms originate in the skin in 97% of cases, are very rare in mucous membranes (such as the larynx), and usually present as rapidly growing, asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules.13 MCCs are usually located on the head (face), extremities (both upper and lower) and, to a lesser extent, the trunk.14 In addition, palpable regional metastatic adenopathies are frequent. Distant metastases usually occur in the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.4,12,15In the thorax, MCC may occur as a primary or secondary tumor.16

The breast is an uncommon site of metastases for virtually any type of tumor, including carcinomas, sarcomas, and hematolymphoid neoplasms,17-19and although metastases generally recapitulate the histologic features of the primary tumor, in this location, they are a diagnostic challenge given their rare occurrence. MCC in the breast, which presents as an exceptionally rare subcutaneous mass,20 can be a primary or secondary tumor,2 and a cautious interpretation of medical records, and imaging, histopathologic and immuno-histochemical findings is essential for its diagnosis.5,8

MCC diagnosis and staging using imaging techniques is achieved through computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography.2 Histo-pathologically, MCC is composed of small round blue cells with fine granular chromatin and high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, high mitotic rate, and occasional necrosis.21,22

The following report presents the case of an elderly man with a subcutaneous nodule in the right breast diagnosed as MCC, a location in which a skin graft had been transplanted years earlier.

Case presentation

On March 4, 2020, an 85-year-old white man went to the breast care service of the Instituto Nacional de Oncología y Radiobiología (National Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology or INOR by its acronym in Spanish) in Havana, Cuba, due to a change in color and an increase in volume and temperature in the right breast. The patient had a history of thermal trauma to the right hemithorax (18 years prior to consultation), which was treated with a skin graft from his right thigh.

Physical examination revealed the following findings: skin changes in the right breast and ipsilateral axillary region with increased volume, as well as a hard, firm and large palpable mass adhering to deep planes. No alterations were found in the breast or left axillary region. After the clinical evaluation, outpatient treatment was prescribed, and breast ultrasound and digital mammography were requested, which were performed the following day (05/03/20).

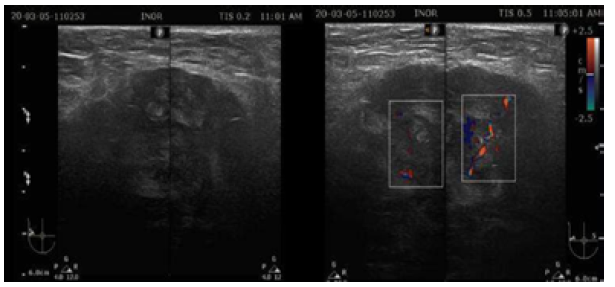

Ultrasound showed that the left breast had no alterations, but the right breast had a fatty breast pattern, an extensive solid nodular area located in the upper outer quadrant and axillary extension, microlobulated margins associated with skin thickening (6mm), and signs of lymphedema of the subcutaneous cellular tissue. This examination established that the right breast lesion was classified as BI-RADS 5; in addition, the right axilla showed lymph nodes classified as BRN-4 according to Rostagno's classification, which corresponds to lymph nodes >3.5mm in size with increased thickness and/or focal thickening of the cortex (Figure 1).

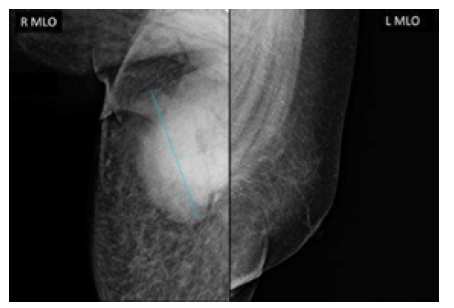

Mammography also showed that the left breast had no alterations, and that the right breast had a fatty breast pattern, increased size with global diffuse distortion of the glandular architecture, skin thickening (6 mm), and trabecular thickening of the subcutaneous cellular tissue. It was also noteworthy that there was an oval nodule with indeterminate margins, approximately 110x84mm, without calcifications and located in the upper outer quadrant towards the axillary extension, as well as lymph nodes with a metastatic appearance in the right axilla. Based on this examination, the right breast lesion was also classified as BI-RADS 5 (Figure 2).

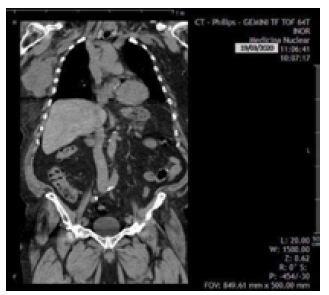

On March 18, 2020, the patient was reassessed during a follow-up consultation by the breast care service, and in view of the ultrasound and mammography findings, confirmatory studies (ultrasound-guided automated TRU-CUT needle biopsy) and extension studies (computed axial tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and blood analysis panel) were performed. Thus, the following day, a simple computed axial tomography of the thorax and abdomen with coronal reconstruction was performed, which showed the following findings (Figure 3):

Hypodense solid mass with irregular borders in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast towards the axillary extension, without calcifications and without infiltration of the pectoralis major muscle.

Metastatic lymph nodes in the right axilla.

No metastases in the pleura, lungs and solid organs of the abdomen; no secondary bone lesions were identified.

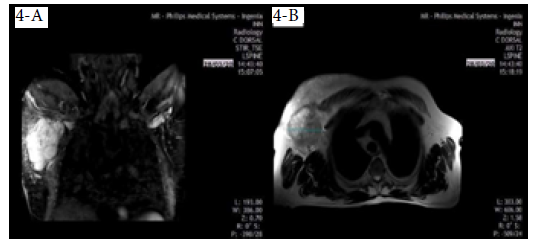

On March 28, 2020, the patient underwent a chest MRI that showed an irregular nodule measuring 9.6x7.4cm, of hyperintense appearance in STIR sequence, with non-circumscribed margins located in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast, extending to the tail of the breast (Figure 4A), and of heterogeneous features in T2-weighted sequences in axial slice (Figure 4B), which did not invade the pectoralis major muscle or the chest wall. Diffuse distortion of the architecture of the right breast was evident in all sequences (BI-RADS 5).

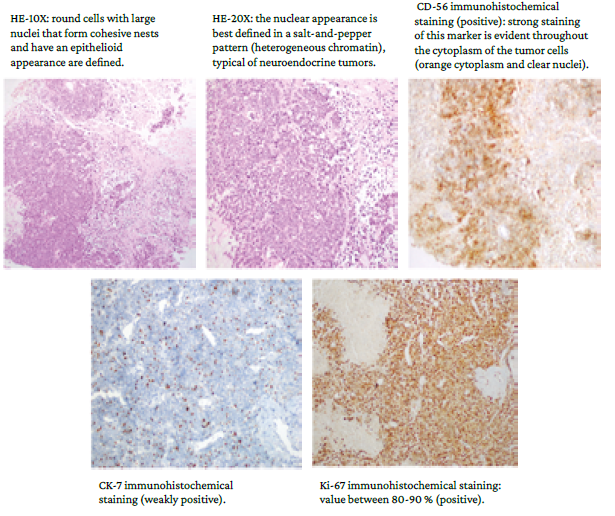

On March 30, 2020, the results of the ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the breast were received (Figure 5). The sample obtained in this procedure was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunohistochemistry. HE staining showed poorly differentiated malignant proliferation with diffuse infiltrative growth pattern alternating with areas of necrosis; uniform medium-sized cells, scant cytoplasm, and nuclei with fine granular chromatin; and atypical mitoses and apoptosis. The immunohistochemistry report showed the following neuroendocrine markers: cytoplasmic CD-56 positive in tumor cells, nuclear CK-7 positive in some tumor cells, and nuclear Ki-67 intensely positive, which translates into a high proliferation rate and poor prognosis.

HE: hematoxylin and eosin.

Source: Images obtained while conducting the study.

Figure 5 Images of histological studies using different staining techniques.

Based on the findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary MCC and reevaluated by the breast care service. The patient also received follow-up by the oncology service in accordance with the treatment protocol established by the INOR.

Discussion

This study describes the clinical characteristics and the diagnostic, imaging and histopathologic findings in a male patient with MCC of the right breast, whose risk factors were age (85 years), skin color, and a history of a burn in the anterior region of the right hemithorax that required skin graft. The latter fact, together with the location of the neoplasm (breast), represent the unique qualities of the case.

As stated by Villa-Blanco & Nabhan13 in a descriptive clinical study that included 3 adult patients treated in a hospital in Cuenca (Spain), the mean age at the time of MCC diagnosis is 76.2 years in men and 73.6 in women, with rare cases in individuals younger than 50 years of age; no cases have been reported in children.

Primary breast MCC is much more common than breast metastasis. However, metastatic tumors in this area often pose diagnostic challenges when they present as solitary masses because they do not have distinct clinical features;16,20in the present case, the history of skin graft as a result of thermal trauma is noteworthy. It should be kept in mind that, rarely, axillary adenopathy may herald a non-breast metastasis with the same caveats.17

In 2019, Korsa et al.16 published the case of a 79-year-old Croatian woman with a history of plaque psoriasis treated with methotrexate, who presented with a palpable, painless tumor in the upper outer quadrant of the breast associated with another 2-cm superficial retroareolar mass located below the discrete skin erythema. In that case, breast ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography allowed the visualization of both lesions, which was also the case in the patient reported in the present study. Similarly, following core needle biopsy and histopathologic analysis, the presence of small, round, blue cells with nested architecture and high mitosis was demonstrated, findings consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

Likewise, Chou et al.,23 in a case report of a 77-year-old woman with MCC, found a clear association of chronic arsenism with two different primary cutaneous carcinomas. In that patient, breast ultrasound and mammography confirmed the presence of a subcutaneous mass and a suspicious axillary node; in addition, as in the present case and the one described by Korsa et al.,16 histopathology revealed small round poorly differentiated blue cells with a high nuclear ratio compatible with MCC. Similarly, Albright et al.,20 in a case report of an 86-year-old woman with MCC, stated that, in addition to the imaging tests performed (mammography and OctreoScan), sentinel lymph node biopsy was also required to confirm the diagnosis.

As demonstrated by Fernández-Figueras et al.24 in a study of 72 tumor cases comparing the immunohistochemical expression of the p27Kip1, p45Skp2 and Ki67 prognostic markers in MCC, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung, and urinary bladder and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, the Ki-67 protein is highly expressed in the majority of MCC cases. However, their value, rather than diagnostic, is prognostic/biological as they are associated with increased proliferation/aggressiveness.

Tondare et al.5 reported the case of a 55-year-old man with MCC in the breast, which was associated with lymphocytic leukemia; in this patient CD-56 and Ki-67 markers were positive and CK-7 was negative. In turn, Ansai25 stated in a review that CD-117 can help distinguish sweat or sebaceous gland tumors from other non-Merkel cell epithelial tumors.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis of MCC includes metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas, lymphomas, and mesenchymal neoplasms.26 Thus, authors such as Llombart et al.2 and Brooks et al.8 have reported the usefulness of immunohistochemical markers in the diagnosis and prognosis of MCC based on neuroendocrine markers for epithelial cytokeratins.

Furthermore, some studies have established that an important differential diagnosis of MCC is primary neuroendocrine neoplasia of the breast, which must demonstrate neuroendocrine marker positivity in more than 50% of the cells. This marker also normally expresses CK-7, estrogen receptors, and progestin receptors, usually associated with ductal or lobular carcinoma.21,23,27

Treatment of primary MCC includes surgery and/or radiation; chemotherapy is usually recommended for advanced cases since this type of neoplasm is highly radiosensitive and within a few months becomes chemoresistant and prone to recurrence. Outcomes in patients with metastases are poor, as evidenced in the patient reported here, with a historical 5-year survival of 13.5%.3

Based on similarities to small cell carcinoma, schedules with platinum and etoposide or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine are most commonly used for first-line chemotherapy in cases of MCC.28 In general, chemotherapy schemes combining carboplatin, cisplatin and etoposide, cyclophosphamide with vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone, bleomycin, or 5-fluorouracil have been used in the treatment of MCC.29

In patients with localized disease, surgical excision with a 1-2cm margin and adjuvant radiotherapy to the primary site are recommended.30 Patients with a positive node biopsy result should undergo a complete lymph node dissection, which in some cases should be followed by radiotherapy, while those with a negative result should undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Nodal basin radiation administered at the same time as radiation to the primary site is also a treatment option for patients with MCC, especially when dealing with large, locally inoperable tumors, with narrow excision margins, tumor involvement that cannot be improved with additional surgery, and involved regional nodes, mainly after sentinel lymph node dissection. In cases of primary MCC, it is recommended to initiate radiotherapy after surgical excision.31

In a retrospective analysis that included data from 6 908 patients with MCC available in the National Cancer Data Base, Bhatia et al.32 found that, after adjustment for the other variables, patients undergoing surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy had statistically significantly improved overall survival compared to patients undergoing surgery alone among those with localized MCC (stage I: HR=0.71; 95%CI: 0.64-0.80; p<0.001, stage II: HR=0.77; 95%CI: 0.66-89; p<0.001).

A few years ago, patients with metastatic MCC were treated with the previously described conventional chemotherapy models seeking a palliative effect. Currently, although there are no randomized controlled trials comparing chemotherapy with immunotherapy, there are promising clinical trials that allow us to recommend immunotherapy as first-line treatment in this type of neoplasm.33,34Avelumab was approved in 2017 by the Food and Drug Agency and subsequently by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of metastatic MCC. Other antibodies such as pembrolizumab (approved in the United States but not in Europe) and nivolumab are currently under study.35,36

Given the low frequency of primary MCC in the thorax, it is crucial for its diagnosis and subsequent treatment to rule out metastases or primary breast cancer from another type of neuroendocrine tumor given the implications for future treatment. In this sense, the complete analysis of clinical, radiological, histopathological, and immunohistochemical findings is decisive in appropriate decision making.

Conclusion

Typically, MCC presents as a rapidly growing, firm skin nodule in sun-exposed areas, contrary to the present case, in which the lesion appeared on the skin graft on the right hemithorax. Recognizing imaging findings suggestive of this neoplasm is of great importance for diagnosis in unusual areas of the body such as the breast.