The literature has shown that different motivational variables impact students' academic engagement and that this, in turn, influences learning behaviour. For example, studies have used Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2017) to show that intrinsic motivation positively impacts engagement (Froiland & Worrell, 2016), as do extrinsic motives, though to a lesser extent (Delaney & Royal, 2017). In the same vein, lack of motivation negatively impacts academic engagement (King & Datu, 2017). Other theoretical approaches that have similarly demonstrated how motivation predicts behavioural engagement include, for example, Expectancy-Value Theory (EVT) (Putwain, Nicholson, Pekrun, Becker, & Symes, 2019).

In our study, the relationship between motivational variables and academic engagement behaviours takes place in a very precise context: the future teacher training process in Chile. For those who will be the mediators of culture for new generations (Falardeau & Simard, 2015), effective engagement of future teachers is crucial to quality training programmes. Engagement depends on what is generally referred to as "teacher motivation". While relevant to the professional training of future teachers, this label has been applied to a broad spectrum of motivation and various motivational variables.

The timing of this study is not coincidence. Recently in Chile, teacher training has undergone reforms to attract better candidates based on the premise that the quality of the education system is determined by the quality of its teachers (Barber & Mourshed, 2007). In this context, incentives such as the "Teacher Vocation Scholarship" (Beca vocación de profesor) programme or discounted or free tuition policies (Agencia de Calidad de la Educación, 2016), have been shown to lack effectiveness in retention rates or in attracting the best students (Observatorio de Formación Docente, 2019). Our educational system has historically been segregated and subject to academic selection (via university selection tests), which generates a vicious cycle in which pedagogy is seen as a less prestigious option for the best students. This already complex situation suffers from high rates of in-service teacher abandonment. According to recent studies, 25% of teachers who entered the school system between 2000 and 2009 quit after five years of teaching (Ávalos & Valenzuela, 2016; López, 2015). There will likely be a significant lack of teachers in the near future (Observatorio de Formación Docente, 2019). Notably, it has been suggested that programme selection systems should include other complementary selection mechanisms that consider, for example, secondary school grades, which may better predict success at university (Centro de Estudios MINEDUC, 2017).

And so, to account for specific objects of motivation within the framework of teacher training programmes, this study attempts to identify motivational variables across three groupings: (a) those that have to do with the profession, (b) those that have to do with the training process, and, finally, (c) those that have to do with aspects that contribute to more profound education.

The first group of variables, related to the teaching profession, include "motivation to become a teacher", understood as the intensity of the desire to become a teacher (Canrinus & Fokkens-Bruinsma, 2014); "motivation to teach" (Roness, 2011); and "altruistic motives" (Bergmark & Westman, 2018; Roness & Smith, 2010). Although these three variables may intuitively appear highly correlated, there is evidence that this is not necessarily so. For example, whereas students of pedagogy may like to teach, they do not necessarily want to become school teachers (Arredondo & Apablaza, 2013; Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2011; Mizala, 2011). Thus, the present study approaches them separately.

A second set of variables, related to the formative process during preservice teacher education, is achieved either through "motivation to remain in a teaching programme" or "motivation for professional training". For this category, we draw on the Self-Determination theoretical perspective (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2017), which distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as well as amotivation (Bruinsma & Jansen, 2010; Vallerand, Blais, Brière, & Pelletier, 1989; Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Deci, 2006). These types of motivational variables have been shown to have explanatory power for academic engagement (Froiland & Worrell, 2016; Hattie, 2009; Robbins et al., 2004). So, while people engage in activities that include a range of mostly intrinsic to mostly extrinsic reasons, researchers have suggested that intrinsic reasons more positively impact subsequent outcomes (e.g., engagement, achievement, and performance) (Baldassarre & Mirolli, 2013; Walker, Greene, & Mansell, 2006). However, the preservice teachers' will to remain in the programme is not enough; it is also necessary that they have the motivation to master the contents of teaching professional training (Day, 2006). The other variable in this grouping (Motivation for professional training) is operationalized from Expectancy-Value Theory (Richardson & Watt, 2014; Wigfield & Cambria, 2010; Wigfield, Tonks, & Klauda, 2009), according to which, expectations for success in the task, and the value they attribute to it, most explain student engagement, achievement, and performance. Specifically, expectancy refers to the feeling of competency in performing a certain task, while value refers to value attributed to that task. Task value has been measured through four components: Perceived utility, interest, attainment, and cost (Wigfield & Cambria, 2010; Wigfield et al., 2009). Different studies have shown that student expectancy and value for a given task are good predictors of task engagement (Bailey, 2015; Gråstén, Watt, Hagger, Jaakkola, & Liukkonen, 2015; Martínez, 2016; Miele & Scholer, 2016; Nagengast, Trautwein, Kelava, & Lüdtke, 2013). In addition, recent studies have shown that these two components are likely to interact one with another (Nagengast et al., 2011; Nagengast et al., 2013; Trautwein et al., 2012).

A third group of motivational variables relevant to the academic formation of teachers include intellectual curiosity (Powell, Nettelbeck, & Burns, 2016; Watson, 2017) and for Academic Reading Motivation (De Naeghel, Van Keer, Vansteenkiste, & Rosseel, 2012; Muñoz , Munita, Valenzuela, & Riquelme, 2018). These variables immediately contribute to students more deeply processing what they learn during professional training (Powell & Nettelbeck, 2014) and an effectively ingrained professional identity (Matsushima & Ozaki, 2015). This makes their pedagogical performance more effective, especially when it comes to motivating students. A teacher that yearns to know more and enjoys learning new things can transmit that desire to students (Viau, 2013). In turn, when students are highly motivated in these areas, we may expect better performance when working as teachers (Tang, Wong, & Cheng, 2015). Next, Academic Reading Motivation (De Naeghel et al., 2012; Muñoz, Valenzuela, Avendaño, & Núñez, 2016), has been shown to be essential to be able to adopt and explore content. Studies have shown that this variable is essential to encourage students to explore text-based content which is primarily mediated by specialized literature in the discipline (e.g., pedagogy, psychology) (Watkins & Coffey, 2004). In this context, it is not enough to want to become a teacher, is essential to have the willingness to acquire professional knowledge through academic reading. Without this mediation, the acquisition of knowledge will probably not be sufficient.

This study proposes that measurements of these motivational variables will provide greater predictive power in gauging potential success in and persistence of students studying pedagogy. Below, we discuss our study of predictive variables for academic engagement in the context of Chile.

Objective of the Present Study

The objective of this study is to distinguish the effects that motivational variables, as a whole, have on engagement. These results are then combined to propose a model of how these variables relate to engagement in training future Chilean teachers. While we expect this will contribute to the design of motivational support mechanisms that will improve learning during university training, the relationship here will also provide a framework for establishing selection criteria of pedagogy candidates.

Hypothesis

Engagement is predicted by motivation to study pedagogy, across intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation variables. As a result of the analysis performed, it is possible to model the effects of the different motivational variables that affect academic engagement.

Method

Participants

In Chile, primary teacher training programmes last between four-and-a-half and five years. For the purposes of the study, the sample consisted of students in their initial, intermediate, and final years of these programmes. As such, first year (n=219), third year (n=257), and fifth or last year (n=259) students from nine public and private Chilean universities located between the IV and the IX regions of Chile were recruited for the study. The universities were chosen to ensure regional diversity and for there to be distribution between public or private institutions.

The total sample group was 764 primary pre-service teachers (84.3% women). The high percentage of women reflects the national average for the gender distribution in this kind of programme (SIES, 2016). The age of participants ranged from 18 to 53 years old, with a mean age of 22.73 years (SD= 4.17) (first year, M=20.46; third year, M=22.41; and fifth year, M=24.79). Of the participants, 11.9% held an academic scholarship because of their high scores in university selection tests, and 79% had early practical experiences within the school system (practicums), in most cases, since their first year.

Measures

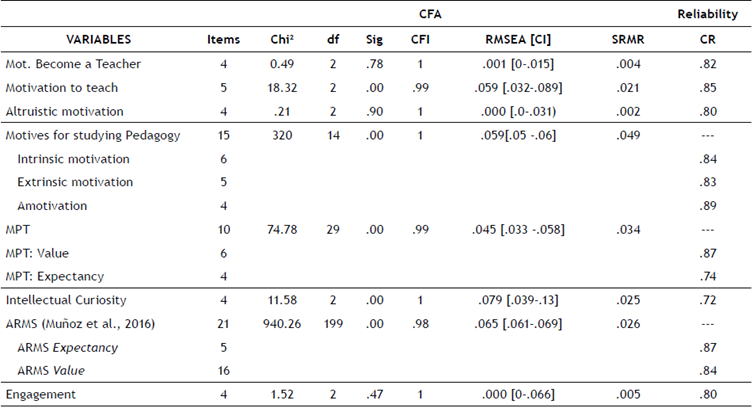

To measure motivational variables related to teacher education, we used the Motivational Inventory for Teaching Education (MITE) (Original: Inventario Motivacional para la Formación Docente; see Valenzuela et al. 2016). This inventory measures: motivation to become a teacher (CR=.82); motivation to teach (CR=.85); altruistic motives (CR=.80); type of motives to remain in a teaching programme (including Amotivation (CR=.89), Extrinsic (CR=.83), and Intrinsic motivation (CR=.84)); Motivation for professional training, including Expectancy (CR=.74) and Value (CR=.87); Intellectual curiosity (CR=.72); and the Academic Reading Motivation Scale that includes Expectancy (CR=.87), Value (CR=.84); and Academic Engagement (CR=.80) (see Table 1).

All scales showed a single factor with acceptable fit indices (e.g., RMSEA <.08) (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006) and high levels of reliability, where the values obtained were >.7 in Composite Reliability (Peterson & Kim, 2013).

Some examples of items are:

Procedures

Data were gathered collectively on campus in a pen-paper questionnaire format at the beginning or the end of the teaching period. In this context, all students present in the first, third, and final years of the programme were invited to participate on a voluntary basis. Data collection was supervised by at least one of the main researchers of this study.

Questionnaire completion did not exceed 30 minutes. As an incentive, participants were rewarded with a movie ticket.

Confidentiality and willingness to participate were ensured in all participants; we respected the statistical and ethical standards for this type of research (Steneck, Mayer, & Anderson, 2010). All participants signed Informed Consents approved by the institutional Ethic Committee.

Analytical Procedures

In order to account for the relationship among variables and with engagement, analysis began with a hierarchical regression that incorporated blocks of variables. This began with sociodemographic variables, was followed by the group of motivational variables related to the profession, then those related to the formative process, and ended with those variables related to intellectual curiosity and motivation for academic reading.

Based on these results and the literature review, a model of the relationship among variables was tested with path analysis (Amos 20) using adjustment criteria proposed by Medrano and Muñoz-Navarro (2017).

Results

Descriptive and Correlational Analysis

In order to determine whether there was a ceiling or floor effect, a contrast between the mean obtained on each scale and the top (6) and bottom (1) score on the same scale was carried out. The ceiling or floor effect aims to determine whether scales discriminate. Results show significant differences (p < .001) for all t-test contrasts between the means and the top/bottom value on each scale.

The highest mean scores among studied variables were motivation to teach, altruistic motives, and motivation to become a teacher. These variables related to the teaching profession grouping variables. Among all variables, both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation had the highest standard deviations (SDs), which, compared to other variables, is evidence of higher heterogeneity.

Likewise, almost all variables considered in this study correlate significantly with engagement. Exceptions are academic scholarship and extrinsic motivation (see Table 1). However, it is important to note that the effect size, though still significant, is minimal in some cases (e.g., age).

Regression Analyses

In order to analyze how student engagement is related to the four groups of variables, while controlling for demographic and academic variables, a multiple regression analysis was carried out. Control variables (demographic and academic variables) were entered in step 1. Variables related to the teaching profession or career (become a teacher, motivation to teach, and altruistic motives) were entered in step 2. Motives for studying pedagogy (amotivation, intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation) were introduced in step 3. Variables related to academic motivation (motivation for academic reading, intellectual curiosity) were entered in step 4. Finally, variables related to mastering professional teaching training (MPT expectancy - value) were introduced in step 5.

The order that variables were introduced was meant to, first, control for some variables and, second, reflect the chronological experience of students entering the programme. Variables more greatly related to processes that can be developed during the period of pedagogical training were left for subsequent steps (see Table 4).

Table 4 Factors predicting students’ engagement in their studies (beta scores)

ARMS= Academic Reading Motivation Scale; MPT= Motivation for Professional Training *= p< .05; ** = p< .01; *** p< .001;

Results indicate that the control variables (gender and age) are very modest predictors of engagement when other steps of variables are entered in the analysis, and they are only sometimes significant.

Among the motivations related to the teaching profession, both motivation to become a teacher and motivation to teach significantly predict engagement. Moreover, despite the entry of new variables to the equation, they continue to be significant. This is not the case for altruistic motivation, despite having a high value, it is not a determining factor that explains the performance of engagement after new variables are added. Teaching profession variables increase the explained variance by 18.5%.

When studying pedagogy, variables related to motivation for (intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation) do not appear to determine engagement. Intrinsic motivation does appear to be a statistically significant factor; however, it loses significance after incorporating academic motivation variables. The motivation for studying pedagogy variables used in this paper increased explained variance by 25%.

The incorporation of intellectual curiosity and motivation for academic reading, and their two components (expectancy and value), also decreased the effect size of other significant variables. This pattern continued in step 5, where incorporating variables related to pedagogical studies (MPT Expectancy-Value) also decreased other effect sizes; this included expectancy for academic reading motivation losing significance.

Regardless, each motivational variable grouping included increased the portion of explained variance, ranging from 1.7% to 51.3% in the last step.

The final model shows that engagement is significantly predicted by a set or group of variables. Within the final model, the best predictors are academic reading motivation (value), MPT (value), and intellectual curiosity; the lowest weight factors are motivation to become a teacher, and motivation to teach.

Modelling the Relations among Predictive Variables of Engagement

After multiple regression analysis, we proceeded to test a relationship model among these variables and academic engagement. In this model, variables that showed significant relationships were incorporated (see Figure 1). The relationships among variables and the resulting academic engagement satisfactorily fit the data: Χ2= 9.93, df=5, p= .077; Χ 2 /df =1.98; TLI= .990; CFI=.998; NFI= .99; RMSEA= .036 [0-.069].

Figure 1 Structural equation model (SEM) of predictors and mediators of academic engagement in preservice teachers.

As shown above, this subsequent path analysis showed that variables related to the profession (motivation to teach and motivation to become a teacher) have less impact on engagement than other variables do. However, it should be noted that motivation to teach mediates other variables. In fact, when excluding this variable, the same model had very poor fit (e.g., RMSEA = .174). We also note that the task component of academic reading motivation and intellectual motivation contribute the most to explaining academic engagement (see Figure 1).

Discussion

Initial assumptions were that variables associated with Self-Determination Theory (specifically, intrinsic motivation or amotivation) would more strongly predict engagement (Abós, Haerens, Sevil, Aelterman, & García-González, 2018; Delaney & Royal, 2017; Kaplan & Madjar, 2017; Renninger & Hidi, 2015). However, these variables do not appear to be significant in explaining academic engagement in this sample of future Chilean professors. This may be due to a decreased motivation to study teaching after having already entered into a teaching programme. Studies in Chile have indicated that students with high amotivation for studying teaching persist in the programme if only to obtain a university diploma (Valenzuela, Muñoz, & Marfull-Jensen, 2018). This phenomenon seems to differ from other contexts, such as in Europe, where teacher motivation is maintained without major alterations over the course of training (Marušić, Jugović, & Lončarić, 2017) or in the first stages of being in-service (Roness, 2011). Indeed, recent studies suggest that motivation to study teaching seem to be strongly conditioned by contextual elements (Tang, Wong, Wong, & Cheng, 2018).

Our model shows that variables related to academic motivation, i.e., motivation for academic reading (value) or intellectual curiosity, and variables related to mastering professional teaching training, were the main predictors of preservice teacher engagement. We also confirm that these are mediated by other motivational variables, which play a fundamental role.

This was consistent with previous studies that isolated the significant effects between these variables and academic engagement, and subsequently with performance. Our results show two structural variables: Motivation to teach, and intellectual curiosity. Motivation to teach impacts academic engagement of these future teachers through intellectual curiosity, motivation to become a teacher, the value of reading academic texts, and the feeling of competence when taking advantage of training opportunities (MPT-Expectancy). On the other hand, intellectual curiosity, in addition to direct effects on engagement, also mediates motivation for professional training (value) as well as the value attributed to reading academic texts.

By explaining the relationships among these different motivational variables and engagement of students in university teacher training programmes, the proposed model may be valuable in selecting future candidates (Pérez Granados, 2014). Such an approach would heavily complement other criteria already used, (e.g., cognitive skills, knowledge, and standardized testing scores, PSU) in selecting university students in Chile. While we focus on students studying on pedagogical programmes (Treviño, Scheele, & Flores, 2014), other researchers may use our framework to study engagement in other programmes.

These variables may also allow candidates to go beyond vocational profiles restricted to a naïve perspective of 'wanting to be a teacher' or 'loving children' (Abramowski, 2010; Avendaño & González, 2012). They also provide further evidence to make it abundantly clear that becoming a teacher inevitably requires student effort and engagement in achieving the theoretical and practical components of the programme. Thus, while motivation to become a teacher is a necessary and an integral part of the teaching career, other motivational variables are required for a student to fully engage with their programme. The results of the present study call for, at least within the Chilean context, the careful consideration that "motivation to become a teacher" or "motivation to teach" may not be enough to explain the teacher training engagement.

Secondly, having confirmed a model for engagement within professional training programmes for future teachers, we note that many of these motivational variables are modifiable through educational interventions. The literature discusses evidence in this sense regarding, for example, motivation to teach (Whitaker & Valtierra, 2018); or academic reading motivation, especially the value assigned to this activity (Muñoz et al., 2016). Other interventions in these variables may also be designed to increase student engagement with the opportunities provided by teacher-training programmes. To this end, ensuring quality in early practical experiences (practicums) and student support may be important steps to avoid demotivation.

Although this research has identified the effect size of different motivational variables in predicting engagement, it is limited in that we did not use the extended versions of all scales. This was done in order to sustain participant interest when responding, and, thus, maintain measure reliability. Fortunately, psychometric characteristics of the short versions of the instruments showed adequate levels of validity and reliability, allowing reliable statistical analysis. Future studies may contrast these results and the actual performance of pre-service teachers in theoretical and practical components of their professional training. However, given the different study programmes across Chilean universities, comparisons would have to be made carefully.

In sum, the present research has allowed for a closer look at the specifics of different motivational variables involved in teacher education and training, and the relationship among them, as related to the academic engagement of future teachers. As we have shown, engagement requires intellectual curiosity, high levels of academic reading motivation, and high motivation (expectancy and value) for professional training. In order to avoid demotivation or drop out, these variables should be taken into account when selecting candidates who are applying for teaching programmes as well as during the training process.