Impulsiveness has been associated with the incapacity to behave reflectively, a deficit of emotional control, the inability to delay gratification (Andreu et al., 2013), behavioural disinhibition (Papachristou et al., 2012; Sánchez-Sarmiento et al., 2013), and novelty seeking (Osorio, 2013), in addition it may also refer to premature, unplanned or risky actions that are inappropriate for the situation, without considering the associated negative consequences (Adan, 2012). In this regard, it has been confirmed that impulsiveness is high during adolescence (Osorio, 2013), frequently linked to aggressive behaviour (Andreu et al., 2013; López et al., 2011) as well as the difficulty to regulate emotions and control behaviour, which increases as the degree of impulsiveness increases (Pedrero, 2009). Likewise, a family environment in which there is an emotion regulation deficit can impact on impulsiveness by increasing it (Beauchaine et al., 2007).

The capacity to express and regulate emotions is acquired through relationships with attachment figures in childhood, and stimulation and good treatment are essential for the development of good regulation of emotions. If this relationship involves the absence of contact and lack of care, the acquisition and development of these emotional capacities, which are necessary for a future emotional life, will be affected, predisposing the individual to more aggressive and impulsive behaviours (Barroso, 2014; Fonagy & Target, 2002; Gómez-Zapiain et al., 2012). The attachment theory is very useful for understanding the development of the capacity of emotion regulation (Mikulincer et al., 2003). This capacity is different for each attachment style (Diamond & Hicks, 2005): secure attachment has the highest rates (Mikulincer et al., 2003), whereas ambivalent attachment has the lowest (Loinaz & Echeburúa, 2012). The type of bond established with the attachment figures in childhood will persist throughout adulthood, determining the adult attachment style (Barroso, 2014), and it is particularly critical during the first years of life (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2011). Likewise, in adolescence, attachment styles become relevant, because they increase the establishment of peer bonds (Delgado et al., 2011) and can have significant influence, either confirming or refuting expectations based on childhood experience, thereby changing the internal models elaborated in childhood (Ortiz et al., 2002). Attachment styles are quite different; each one presents specific emotions of greater or lower intensity. In secure attachment, regulation of emotion predominates (Zapata, 2016), expression of anger is controlled and constructive and displays a lower tendency (Mikulincer, 1998) plus there is also adaptive coping (Páez et al., 2006). In the avoidant style, emotions of rage and hostility are predominant (Garrido-Rojas, 2006), along with low emotional expression and high control (Balluerka et al., 2011). In the ambivalent attachment style, there is a predominance of high emotional expressiveness (Kerr et al., 2003), a deficit in control of anger and impulsiveness (Loinaz, 2011; Mikulincer, 1998), low autonomy (Mikulincer et al., 2003), hypersensitivity to negative emotions, and intense expressions of anxiety (Barroso, 2014).

The first early affective experiences with attachment figures in infancy establish self-schemas and schemas regarding others, defined as internalised patterns of the interactions one has had with others (Estévez, 2013). The more harmful and prolonged the painful circumstances, the greater the likelihood of long-lasting and profound consequences (Wills & Sanders, 1997). The influence of these circumstances is more intense in early childhood and declines progressively, giving way to the influence of peer relations and school relations as the child matures (Young & Klosko, 2001). These schemas bias the interpretations of subsequent events (Young et al., 2013) and generate knowledge and expectations regarding one’s self-value, the behaviour of others and the response to one’s needs (Soares & Dias, 2007). Schemas influence the way people feel, think, and behave as well as the way they relate to others. If childhood experiences were negative and the child’s emotional needs were not satisfied, the schemas become maladaptive, turning into generalised dysfunctional schemas regarding oneself and others (Young et al., 2013). The schemas differ in each attachment style. Secure attachment presents positive schemas respecting oneself and others, whereas anxious attachment involves negative self-schemas, leading the person to self-disparagement. Avoidant attachment includes negative schemas related to others, leading the individual to withdraw emotionally from others (Márquez et al., 2009).

Few studies address the relation between adolescent impulsive behaviour and attachment (Estévez et al., 2018; Helbert & Lacayo, 2019), and even fewer tackle their relation with early schemas. However, it is necessary to study both constructs linked to the childhood experiences present in adolescents with high impulsiveness, in order to expand highly relevant knowledge for our comprehension of impulsive behaviour and to establish the risk factors so as to make adequate decisions concerning the appropriate therapeutic approach. The main goals of the present study are to analyse the relation between attachment styles, early maladaptive schemas, and impulsive behaviour, as well as, to confirm the predictive role of the first two on impulsiveness. Lastly, we shall study the mediating of early maladaptive schemas in the relation between attachment and impulsive behaviour. Thus, the hypotheses of this present study were first, that dysfunctional attachment styles, early dysfunctional schemas and impulsivity increase or decrease in parallel. Second, dysfunctional attachment and dysfunctional schemas predict the development of impulsivity. Finally, dysfunctional attachment triggers the development of impulsivity through the presence of early dysfunctional schemas.

Method

Participants

The sample is composed of 1533 adolescent students, 826 males and 707 females, between 14 and 18 years of age (M = 15.76, SD = 1.25). They appertain to twelve Fiscal Educational Units from the different urban (60%) and rural (40%) sociodemographic sectors of the Portoviejo District of the Province of Manabí in the Republic of Ecuador. The official Ecuadorian agencies (National Council of Control of Narcotics and Psychotropic Drugs, 2005), currently known as the Technical Secretariat of Drugs (SETED), were consulted to obtain the sample. The target population was the fiscal educational units of adolescent students, in 10th grade of Basic Primary Education, and 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year of high school. As a reference for determining the sample design, we used the Report on the Second National Survey of Middle Education Students on Drug Use (2005) of the Ecuadorian Republic. The educational units were selected, and we acquired the database from the Ministry of Education Zone 4 Coordination, district 13D01, corresponding to the district, established parish, area of institution (urban or rural), which is related to the Fiscal Educational Units and representative of the different sociodemographic areas in the Portoviejo District. Sample size was calculated taking into account the confidence level of the sample and the ratio with the margin of error (variation between the results obtained in a sample and their inference in the population). The confidence level employed was .95 with a margin of error criterion of .015. In view of the sampling characteristics, we estimated a correction factor of 2 for the design effect in order to increase the sample size and decrease the variability of the observations. Finally, sample size was increased in order to compensate for a possible 10% of missing responses.

Each educational unit had a likelihood of being selected that was directly proportional to the number of 10th grade classes of General Basic Primary Education-BPE and General Unified High School-BGU (1st, 2nd and 3rd grade of High School). In the educational units that had a higher number of classrooms than the sampling interval, various classes could be selected. The selection criterion for the strata was the representativeness criteria corresponding to the capital of Manabí in the Republic of Ecuador. This study will represent both parishes (urban and rural) in the different educational units. The sample was made up of: (a) the Capital of Manabí, Portoviejo, with two parishes: urban and rural, and (b) 12 educational units belonging to both parishes, that is, a total of 1,533 adolescents belonging to 12 educational units and parishes.

Instruments

Attachment. CaMir-R (Balluerka et al., 2011). This instrument is the reduced version of the CaMir (Pierrehumbert et al., 1996). It measures representations of attachment, evaluating present and past attachment experiences and family functioning. It consists of 32 items divided into 7 dimensions, of which 5 refer to representations of attachment (Security: availability and support of the attachment figures; Family concern; Parental interference; Self-sufficiency and resentment against parents; and Childhood trauma) and the remaining two dimensions refer to the representations of the family structure (Parental authority and Parental permissiveness). The scale of “Security: availability and support of attachment figures” refers to the perception of having felt and feeling loved and being able to trust and rely on the attachment figures in case of need.

The “Family concern” scale refers to intense separation anxiety regarding one’s loved ones and extreme present concern for the attachment figures. The “Parental interference” scale alludes to childhood memories of having been overprotected, fearful, and having felt concern about being abandoned. The “Value of parental authority” scale is concerned with the positive appraisal of family values of authority and hierarchy, whereas the scale of “Parental permissiveness” refers to childhood memories of having suffered a lack of limits and parental guidance. The “Self-sufficiency and resentment against parents” scale alludes to feelings of dependence and emotional reciprocity and resentment towards loved ones. Finally, the “Childhood trauma” scale refers to childhood memories of having suffered from lack of availability, violence, and threats from attachment figures. The questionnaire is rated on a 5-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The values of internal consistency in the Spanish adaptation are satisfactory (the alpha value in the different subscales ranges from .60 to .85). In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .90 (Security: availability and support of the attachment figures α = .90; Family concern α = .85; Parental interference α = .71; Self-sufficiency and resentment against parents α = .83; and Childhood trauma α = .83; Parental authority α = .69; Parental permissiveness α = .68).

Schemas. Schema Questionnaire-Short Form-3 (YSQS3, Young, 2005). In the present study, we used the Spanish adapted version set forth by Calvete et al., (2005). This questionnaire assesses the early maladaptive schemas proposed by Young. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale: 1 = totally false, 2 = mostly false, 3 = more true than false, 4 = sometimes true, 5 = mostly true, and 6 = describes me perfectly. In this research, only 60 items were used to evaluate the following schemas: Emotional Deprivation, Abandonment, Abuse, Social Isolation, Defectiveness, Failure, Dependence/Incompetence, Vulnerability to Harm, Enmeshment, Subjugation, Self-Sacrifice, Emotional Inhibition, Unrelenting Standards, Entitlement, Insufficient Self-Control, Approval Seeking, Negativity, and Punitiveness.

The “Emotional Deprivation” schema refers to the belief that support or emotional needs are not adequately met by others. The “Abandonment” schema is based on the belief that significant others will not provide the necessary emotional support or protection because sooner or later, they will leave the person for someone better. The “Abuse” schema describes the belief that others will harm, abuse, humiliate, deceive, lie, or take advantage of one, and it will sometimes contain the belief that the harm is intentional or the result of negligence. The “Social Isolation” schema includes the feeling that one is isolated or different from the rest of the world and that one is not part of any group. The “Defectiveness” schema describes the feeling that one is internally defective, unloved, unwanted, or invalid and inferior in important aspects of life. The “Failure” schema manifests the belief that one has failed, that one will inevitably fail, or that one is a fundamentally inadequate person in comparison with other people in areas of achievement.

The “Dependence or Incompetence” schema consists of the belief that one is unable to handle one’s everyday responsibilities in a competent manner, without considerable help from others. The “Vulnerability to Harm” schema involves an exaggerated fear that at any time a catastrophe, attack, disease, or disaster will occur and that one will not be able to prevent it. The “Enmeshment” schema refers to the excessive seeking of intimacy and emotional involvement with one or more persons to the point of compromising one’s own individual identity, displaying the belief that it is impossible to survive or be happy without the constant support of those people. The “Subjugation” schema implies an excessive surrender to the control of others and the renunciation of one’s own rights because one feels coerced by others, in order to avoid reactions of anger, or possible abandonment. The “Self-sacrifice” schema consists of the exaggerated and voluntary fulfilment of the needs of others in everyday situations, at the expense of the gratification of one’s own needs. The “Emotional Inhibition” schema refers to the excessive inhibition of one’s behaviour and feelings in order to avoid the disapproval of others. The “Unrelenting Standards” schema involves the conviction that one must strive to meet very high internalised standards for oneself and for others. The “Entitlement” schema refers to the presumption that one is superior to others and therefore, deserving of rights and privileges. The “Insufficient Self-control” schema implies a deficit in self-control and frustration tolerance in achieving personal goals, or in controlling the excessive expression of one’s impulses in addition to an exaggerated avoidance of discomfort, pain, conflict, confrontation, or responsibility. The “Approval Seeking” schema involves the excessive seeking of the approval, attention, and recognition of others, submitting one’s self-esteem to the opinions of others, showing excessive concern for appearances, seeking admiration, and hypersensitivity to rejection. The “Negativity/ Pessimism” schema consists of focusing on the negative aspects of life, minimising positive or optimistic aspects, as well as the widespread belief that things will go wrong. The “Punitiveness” schema has to do with the belief that people should be punished for their mistakes, a tendency to anger, intolerance and impatience, and a difficulty to forgive their own or others’ mistakes.

The Spanish version of the YSQ-S3 presents good psychometric properties, its structure factor has been confirmed, and the factors have good internal consistency (Calvete et al., 2005). Prior studies with the YSQ-S3 have shown adequate alpha coefficients for the subscales, except for the study of Stopa et al. (2001), where the alpha was very low for Vulnerability to Harm (α = .07). The short version used in this study was developed with the items based on the long version of the SQ, which were translated into Spanish by Cid and Torrubia in collaboration with Young. The Spanish SQ has shown good reliability and correlations with depression, positive and negative affect, and self-esteem (Cid & Torrubia, 2002). In this study, the Cronbach alpha was .97 (Emotional Deprivation α = .68; Abandonment α = .70; Abuse α = .65; Social Isolation α = .64; Defectiveness α = .56; Failure α = .62; Dependence/Incompetence α = .66; Vulnerability to Harm α = .68; Enmeshment α = .66; Subjugation α = .64; Self-Sacrifice α = .71; Emotional Inhibition α = .70; Unrelenting Standards α = .69; Entitlement α = .71; Insufficient Self-Control α = .69; Approval Seeking α = .65; Negativity α = .62; Punitiveness α = .65).

Impulsiveness was measured with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS 11; Patton et al., 1995). This scale was designed to assess impulsiveness considering the construct from a multidimensional perspective. It consists of 30 items grouped into three subscales: Cognitive Impulsiveness, related to restless or careless thinking, a tendency to making quick decisions; Motor Impulsiveness involves acting hastily without previous reflection and can be considered as a deficit in behavioural inhibition or self-control; Unplanned Impulsiveness refers to actions taken without planning ahead, that is, it evaluates the planning and organisation of future actions. It is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (rarely or never happens) to 4 (always or almost always happens). The internal consistency values in the Chilean adaptation, used in this case, are acceptable (the Cronbach alpha value of the full scale was .77). In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .81. (Cognitive Impulsiveness α = .61; Motor Impulsiveness α = .64; Unplanned Impulsiveness α = .62).

Procedure

This is a quantitative sectional study. First of all, we obtained the informed consent forms from the parents and/or guardians of the adolescents who participated in the study. We informed the parents of the rules to follow to complete the questionnaires, the approximate time needed to complete them, and the aspects we intended to measure. We also told them that participation was voluntary, and that the data were confidential and anonymous, and we provided the contact details of the reference researchers so they could be contacted if necessary. During the administration of the questionnaires, in pencil-and-paper format, the researcher remained in the classroom until all the students handed in their completed questionnaires. After handing in the questionnaires, the students received a pencil and a participation certificate to thank them for their collaboration. The present study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013).

Statistical analysis

First, bivariate correlations were calculated to study the relationships between impulsive behaviour, early maladaptive schemas, and attachment, using Pearson’s r. Next, stepwise multiple linear regression was carried out to analyse the predictive role of early maladaptive schemas and adult attachment in the presence of impulsive behaviour. Lastly, we studied the mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between attachment styles and impulsive behaviour using a three-step linear regression analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986). In the first step, dysfunctional attachment styles should be significantly associated with impulsivity. In the second step, dysfunctional attachment styles should be significantly associated with the mediating variables. In the third and final step, the relationship between dysfunctional attachment styles and impulsivity should be significantly reduced by adding the mediating variables to the model. The effect of mediation was evaluated by means of the bootstrapping procedure that provides 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 statistical software.

Results

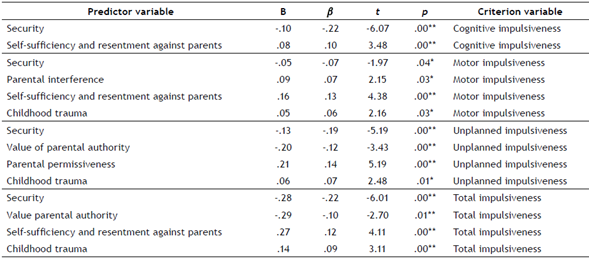

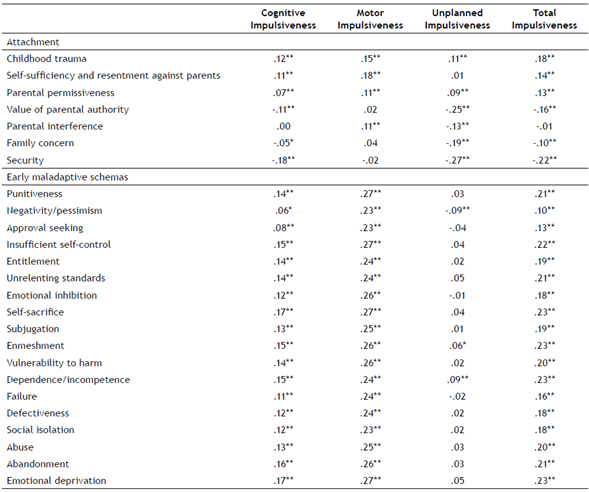

First, the relations between impulsiveness, early maladaptive schemas and attachment were measured (Table 1).

Table 1 Correlation between impulsiveness, early maladaptive schemas, and attachment

*p < .05. **p < .001.

Primarily, with regard to attachment styles, childhood trauma and parental permissiveness were statistically, significantly, and positively related to total impulsiveness. The value of parental authority, parental interference, family concern and security were negatively related to unplanned impulsiveness. Lastly, self-sufficiency and resentment against parents were positively associated with motor impulsiveness.

In terms of early maladaptive schemas, punitiveness, negativity, approval seeking, insufficient self-control, entitlement, unrelenting standards, emotional inhibition, self-sacrifice, subjugation, enmeshment, vulnerability to harm, dependence, failure, defectiveness, social isolation, abuse, abandonment, and emotional deprivation were positively related to motor impulsiveness, and these relationships were statistically significant.

Secondly, the predictive role of attachment and early maladaptive schemas on impulsive behaviour was tested (Table 2). The results show that security (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .00), the value of parental authority (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .00), parental permissiveness (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .00), self-sufficiency and resentment against parents (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .00), childhood trauma (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .03), and the negativity/pessimism schema (R = .40, R² = .16, R² = .16, p = .00) are predictors of impulsive behaviour.

Table 2 The predictive role of attachment and early maladaptive schemas in impulsive behaviour

*p < .05. **p < .001.

Influence of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between attachment and impulsiveness

First of all, we analysed the predictive role of attachment styles on impulsive behaviour (Table 3). As can be observed, the attachment styles of security and self-sufficiency as well as resentment against parents predicted cognitive impulsiveness. On the other hand, the attachment styles of security, parental interference, self-sufficiency and resentment against parents, and childhood trauma predicted motor impulsiveness. Furthermore, the attachment styles of security, value of parental authority, parental permissiveness, and childhood trauma acted as predictors of unplanned impulsiveness. Likewise, the attachment styles of security, value of parental authority, parental permissiveness, self-sufficiency and resentment against parents, and childhood trauma predicted total impulsiveness.

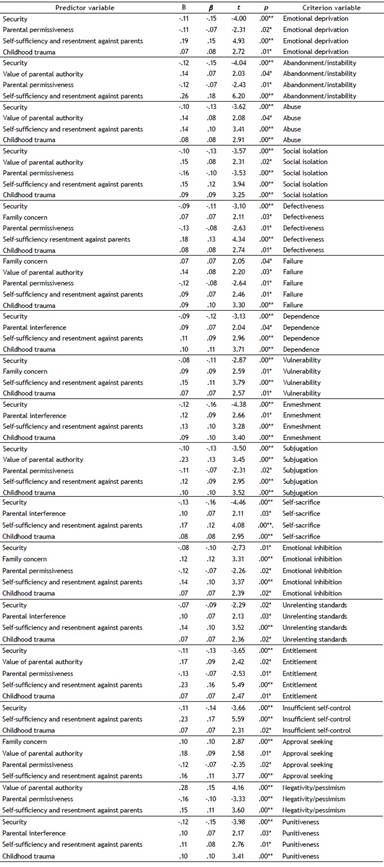

Next, we examined the predictive role of attachment styles on early maladaptive schemas (Table 4). The results show that the security attachment style predicted all the early maladaptive schemas except for the failure, approval seeking and negativity/pessimism schemas. Likewise, parental permissiveness predicted the schemas of emotional deprivation, abandonment, social isolation, defectiveness, failure, subjugation, emotional inhibition, entitlement, approval seeking, and negativity. Self-sufficiency and resentment against parents predicted all the early maladaptive schemas. It was also shown that childhood trauma predicted all the schemas except for abandonment, approval seeking, and negativity. The value of parental authority also predicted the schemas of abandonment, abuse, social isolation, failure, subjugation, entitlement, approval seeking, and negativity. Family concern predicted defectiveness, vulnerability, emotional inhibition and approval seeking. Lastly, parental interference predicted dependence, enmeshment, self-sacrifice, unrelenting standards, and punitiveness.

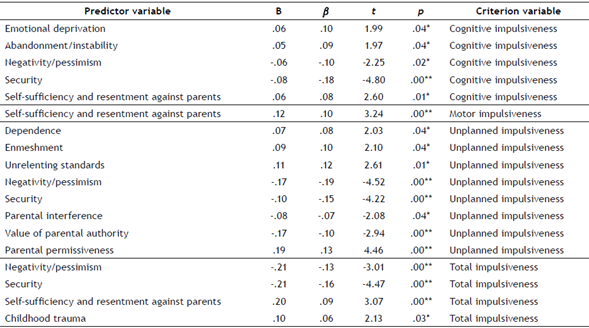

Finally, early maladaptive schemas were associated with impulsive behaviour after controlling for the association between attachment and impulsiveness (Table 5).

Table 5 Mediational analysis of the indirect effect of attachment on impulsive behaviour through early maladaptive schemas

*p < .05. **p < .001.

As can be observed, 20% of the variance in the relationship between security and cognitive impulsiveness, and 25% of the variance in the relationship between self-sufficiency and resentment against parents and cognitive impulsiveness was explained by early maladaptive schemas. In addition, 25% of the variance in the relationship between self-sufficiency and resentment against parents and motor impulsiveness was explained by early maladaptive schemas. Similarly, 23.07% of the variance in the relationship between security and unplanned impulsiveness, 15% of the variance in the relationship between the value the parental authority and unplanned impulsiveness, and 9.5% of the variance in the relationship between parental permissiveness and unplanned impulsiveness are explained by early maladaptive schemas. Thus, 25% of the variance in the relationship between security and total impulsiveness, 25.92% of the variance in the relationship of self-sufficiency and resentment against parents and total impulsiveness, and 28.57% of the variance in the relationship between childhood trauma and total impulsiveness are explained by early maladaptive schemas.

Discussion

The first objective of this study was to analyse the relationship between impulsiveness, attachment styles, and early maladaptive schemas. The results show that as childhood trauma and parental permissiveness increase, impulsiveness also increases. These results are in accord with studies that indicate that having suffered childhood abuse is associated with higher levels of impulsiveness (Kokoulina & Fernandez, 2014). In addition, this study shows that the value of parental authority, parental interference, family concern, and security increase as unplanned impulsiveness decreases. These results could be due to the fact that the secure attachment style presents the best rates of emotion regulation (Mikulincer et al., 2003). Finally, in this study, self-sufficiency and resentment against parents were observed to increase as motor impulsiveness increases. This is in the line of studies relating abuse toward parents with impulsiveness, due to a deep aversion to being guided or supervised (Aroca-Montolio et al., 2014).

Regarding early maladaptive schemas, this study shows that they increase as motor impulsiveness increases. Primarily, we note that the results are novel because few studies relate early maladaptive schemas to impulsive behaviour. These results could be explained due to the strong relationship between impulsive behaviour and aggressiveness (Vigil-Colet et al., 2008). Thus, impulsive people have been characterised by an absence of reflective attitudes and a deficit in the regulation of emotions. This may explain the positive relationship between the schema of insufficient self-control and impulsiveness (Tharp et al., 2013; Vigil-Colet et al., 2008). As for the schema of entitlement, this may be due to the link between narcissistic personality traits and aggressive behaviour (Esbec & Echeburúa, 2010). Likewise, we note that both the grandiosity and the insufficient self-control schemas have been associated with drug use, which is also strongly linked to impulsiveness (Calvete & Estévez, 2009). Regarding the abandonment schema, in previous studies, it has been considered as fear of real or imaginary abandonment and has been linked to violent behaviour (Esbec & Echeburúa, 2010). Likewise, schemas of defectiveness, dependence, and failure are associated with impaired self-esteem, frequently related to violent behaviour (Estévez et al., 2006). Finally, the schema of subjugation is related to deficits in social skills and assertiveness, aspects that are associated with aggressiveness (Roca, 2014).

The second objective of the study focused on studying the predictive role of attachment and early maladaptive schemas in impulsive behaviour. The results obtained show that security, the value of parental authority, parental permissiveness, self-sufficiency and resentment against parents, childhood trauma, and the negativity/pessimism schema predict impulsive behaviour. These results are novel because very few studies relate attachment to impulsive behaviour. However, these data may be in line with studies indicating that the authoritarian parental style (Negrete & Vite, 2011) and abuse suffered in childhood are associated with high impulsiveness (Fernández et al., 2002). Also, previous studies point out that violent people may have suffered permissive or negligent educational practices with parental absence, either physically or psychologically (Aroca-Montolío et al., 2014). Self-sufficiency and resentment against parents may be explained by studies indicating that impulsive, aggressive people behave violently in response to accumulated internal tension (Amor et al., 2009).

Finally, the mediator effect of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between attachment and impulsiveness was analysed. The results show that early maladaptive schemas mediate the following relationships between variables: cognitive impulsiveness and security; cognitive impulsiveness and self-sufficiency and resentment against parents; motor impulsiveness and self-sufficiency and resentment against parents; unplanned impulsiveness and security; unplanned impulsiveness and the value of parental authority; unplanned impulsiveness and parental permissiveness; total impulsiveness and security; total impulsiveness and self-sufficiency and resentment against parents; and finally, total impulsiveness and childhood trauma. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between impulsiveness and attachment. Nevertheless, these results may be in the line of studies that point to schemas involving a lack of limits- that is, schemas of entitlement and insufficient self-control- would be linked to the desire for immediate gratification and, therefore, to impulsiveness (Calvete & Estévez, 2009).

Likewise, attachment styles influence the development of the emotion regulation capacity (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2017), an aspect that is deficient in impulsive behaviour (Andreu et al., 2013). In addition, previous studies that have linked early maladaptive schemas and parental styles have considered that the impulsive parental style predicts the schema of grandiosity and insufficient self-control, just like the parental style of imperfection predicts the schemas of abandonment, emotional deprivation, abuse, social isolation, defectiveness, dependence, vulnerability, attachment and failure (Estévez & Calvete, 2007).

This study also has several limitations. Mainly, as it is a cross-sectional study, it precludes obtaining causal relationships among the variables. On the other hand, we used self-reported measures, which can distort the results, especially when evaluating variables such as attachment. Therefore, the conjoint use of these measures with others, such as interviews or observational measures, could contribute to obtaining more accurate results. In the specific case of the attachment measurement, it must also be taken into account that it is a retrospective report, so there may be difficulties or distortions in the recall, aside from the distortions of the self-report itself. Moreover, adolescence or early adulthood is not the best evolutionary moment to appraise aspects related to attachment, as this is a stage of constructing identity and of complicated relationships with parents, in which it is difficult to admit certain feelings towards them.

Despite the limitations, the results are innovative because few studies address the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and attachment styles and impulsive behaviour. Knowledge of the role played by early maladaptive schemas and attachment styles as risk factors involved in the establishment of impulsive behaviour may be useful to implement preventive strategies and an appropriate therapeutic approach.