There are many constructs that characterise people’s perceptions of their work, including work commitment (Yulianto et al., 2022); work involvement (Irmayani et al., 2022); job involvement (Agarwal et al., 2022); intrinsic/extrinsic motivation (Kanungo & Hartwick, 1987); workplace dignity (Sainz et al., 2021); work values (Timms, 2018); and flow at work (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989; Rodríguez et al., 2017). However, work orientation has the distinction of examining how work connects with people’s lives and is, therefore, an appropriate construct for evaluating the impact of work on happiness (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003; Wrzesniewski, 2003) or human flourishing (Seligman, 2011). The aims of this study are first to explore work orientation in twelve Ibero-American countries; and second, to investigate whether work orientation affects the flourishing life of adults in twelve Ibero-American countries.

Work orientation

Work orientation is conceptualised as an indicator of “preferences or tendencies to value specific types of incentives inherent in the work environment” (Malka & Chatman, 2003, p. 738). From this perspective, we can distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic work orientations. Intrinsic orientation is associated with opportunities for intellectual fulfilment, creative self-expression, and the pleasure associated with mastering the task at work. Extrinsic orientation focuses on the expectations and value of remuneration, and views work mainly as a means to obtain a financial reward (Malka & Chatman, 2003).

According to Wrzesniewski (1999), the concept of work orientation includes the individual’s beliefs regarding the role of work in his or her life as a whole and what they are searching for in their careers. Moreover, Robert Bellah and colleagues (1985) suggest that there are three types of orientation to work: job, career, and vocation. These reflect the different ways in which people are related to their work. In the job sense, work is a way to earn enough money to support a person’s life outside of their job. In the career sense, work marks a person’s advance in life by way of success in their profession. In the case of job or career, the occupation has little to do with the rest of the person’s life. Indeed, job and career orientations represent extrinsic work values, given that a person identified with job orientation is mainly focused on materialist aspects, and career orientation is motivated by high prestige (Bacher et al., 2022). Finally, for those who have a calling, work is one of the most important parts of their life and motivates the desire to make the world a better place. In a calling orientation, on the other hand, work is part of a person’s identity, consequently, it represents intrinsic work values.

Wrzesniewski and colleagues (1997) were the first to confirm that the distinction proposed by Bellah between job, career, and calling could be of interest due to its potential application to organisational psychology. The authors developed a questionnaire called the Work-Life questionnaire that provides three brief scenarios describing individuals who approach work as a job, a career, or a calling. The authors found that work orientation depends more on a person’s outlook than on the type of task. They showed that all three orientations could occur in any occupation, and that the three orientations are equally represented in different occupations. In addition, Dobrow and Tosti-Kharas (2011) argue that work orientation describes a person’s orientation toward work in a general sense rather than toward their current job.

Work orientation has been the focus of much research because of its impact on personal life and in the workplace (Cardador et al., 2011; Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, 2011; Malka & Chatman, 2003; Warr & Inceoglu, 2018). A recent study has shown that adults with a job orientation reported low levels of work engagement and work centrality, while moderate and high levels of work engagement and work centrality were reported by adults with career and calling orientations respectively. Furthermore, career orientation is associated with shorter job tenure, more excellent turnover intentions, and more career comparisons (Mantler et al., 2021).

Duffy et al. (2015) linked work orientation with other indicators of well-being such as life satisfaction. Wrzesniewski and colleagues (1997) found that the calling orientation was associated with superior benefits such as better health and higher levels of life and job satisfaction. Mantler et al. (2021) found that career orientation was related to less career satisfaction. Other studies have shown that a calling at work is associated with flourishing explaining 15% of the variance (Erum et al., 2020).

A longitudinal study encompassing couples in which one was employed and the other was unemployed has shown that a high level of incongruence in work orientation be tween couples was associated with poor job satisfaction for employed partners over time (Jiang & Wrzesniewski, 2022). In addition, a recent study indicated that employees with a higher sense of a calling orientation moderated the negative impacts of uncertainty in times of pandemic, while employees with a higher sense of a job orientation were more impacted by uncertainty (Zhang, 2022).

In summary, there is evidence of the impact of work orientation on well-being or happiness. However, as far as we know, there has been no research on the relationship between the different types of work orientation (especially job, and career) and the deep concept of happiness signified by human flourishing, particularly in cross-national studies in the context of Ibero-American countries.

Flourishing

In an attempt to identify an adequate concept to measure happiness, a growing number of authors have appealed to the notion of flourishing. Although the notion of subjective well-being, understood as the individual’s cognitive and emotional evaluations of their life (Diener et al., 1999), has often been used to measure happiness, recent literature has remarked that an evaluation of happiness needs a more complete approach (Crespo & Mesurado, 2015; Willen et al., 2022). For Seligman (2011), the flourishing construct is a notion that allows us to better understand and measure happiness.

Flourishing is a modern concept of happiness that consists of a much broader range of states and outcomes, including mental and physical health, but also encompassing happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships (VanderWeele, 2017). In a similar vein, Crespo and Mesurado (2015) argue that flourishing, as a construct that includes both hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions, is a richer way of assessing a person’s well-being than mere subjective well-being, or what is commonly known as “happiness”. For Fredrickson and Losada (2005, p. 678), to flourish means “to live within an optimal range of human functioning, one that connotes goodness, generativity, growth, and resilience”. Other authors refer to flourishing as “a combination of feeling good and functioning effectively” (Huppert & So, 2013, p. 837). According to Fowers and colleagues (2010), “flourishing is a pattern of activity in which one finds meaning, purpose, and personal growth through pursuing worthwhile goals in positive, collaborative relationships with others, all of which is inseparable” (Fowers et al., 2010, p. 142). Seligman (2011, p. 16) speaks of “an arrangement of positive emotion, engagement, meaning, positive relationships and accomplishment”.

Studies have found beneficial effects on health, society and the economy for those with a flourishing life (Burns et al., 2022; Ignacio et al., 2022; Keyes & Simoes, 2012; Keyes, 2005). Furthermore, for Keyes (2002), flourishing is a construct that features emotional, psychological and social well-being aspects. Keyes defines emotional well-being as the presence or absence of positive feelings about life (Keyes, 2002). Psychological well-being refers to the individual’s perception of fulfilment in their personal life (Keyes, 2002). Social well-being characterises the relationship between individuals and society-if individuals feel they belong to and are accepted by their communities; they perceive themselves as contributing to society (Keyes, 2002). A combination of high levels of emotional, psychological, and social well-being makes a life a flourishing life (Keyes, 2013; Piqueras Rodríguez et al., 2022). Later studies have suggested that Keyes’ conceptualisation of flourishing is the most complete (Huppert & So, 2013).

The present study

Work orientation is an important topic for employees and employers. Previous studies have found that work orientation has an impact on personal life, and depends more on a person’s outlook than on the type of task (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). To the best of our knowledge there is only one study that has analysed the relationship between a vocational calling at work and flourishing (Erum et al., 2020). This study suggests that a calling gives meaning and purpose to one’s work aimed at making a positive contribution to society which, in turn, increases life satisfaction, well-being and therefore flourishing. However, it remains unclear what role the other types of work orientation play in human flourishing. This paper aims to fill this gap. Consequently, the particular interest of this study is analysing and examining the effect of work orientation (job, career and calling) on human flourishing in different nations.

There are studies regarding human flourishing in European countries (Huppert & So, 2013) and throughout countries and continents such as South Australia, South Korea, and Africa (Keyes, 2013). However, there have been no cross-national studies carried out in Ibero-American countries.

Ibero-America consists of 22 countries which share two main languages: Spanish, 20 countries, and Portuguese, in the case of Portugal and Brazil. The world values survey (https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp) characterises Ibero-American countries with high levels of traditional values, in other words, cultures that emphasise the importance of religion, family relationships, recognition of or obedience to authority and traditional family values. They also show a moderate level of self-expression values: they give moderated priority to tolerance of ethic of gender minorities, environmental policy and involvement in the political and economic life of their countries.

Work orientation and human flourishing cannot be fully understood without considering the cultural context in which an adult works and the society within which adults interact. Thus, cross-cultural studies can provide more information on the relationship between work orientation and flourishing life than studies conducted in a single national context. Empirical research analysing the relationship between work orientation and flourishing in different Ibero-American countries would allow us to discover common patterns of behaviour and thus obtain more robust conclusions. To develop this study two European countries were chosen, Spain and Portugal, from which the largest population of Latin American immigrants emigrated. Also, the 10 Latin American countries chosen are those with the largest surface area and population. Consequently, based on the literature review, the objectives of this study are, first, to explore work orientation in twelve Ibero-American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay); and second, to investigate whether the three work orientations proposed by Bellah and colleagues (1985) (job, career, and calling) affect human flourishing in the twelve countries.

Method

Participants and procedures

The G*Power programme was used to calculate the sample size per country. The programme suggested a sample size of 210 participants with 95% power, an alpha error probability of .05 and an expected effect of .06. Based on this estimation the target was to obtain 250 participants per country, the selection of the sample was non-probabilistic.

A total number of 3000 adults from 12 different countries participated in this study. The countries represented are Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Perú, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay. The sample was recruited with the snowball method. The average age of the participants was between 38.6 and 42.8 years, the percentage of women ranged between 50% and 70% of the sample, on average the participants had between 2 and 3 children and finally most of them had university or postgraduate studies (between 80% and 97%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in the different countries.

The research project was developed and coordinated in Argentina and Colombia. Moreover, ten partners, one per country, were contacted to request their participation in disseminating the survey. The partners worked at different institutions, including research centres, universities, colleges, and NGOs. The partners distributed the online survey through their contact lists via mail using the snowball method. National adult samples were collected by means of a survey designed specifically for this purpose and available at www.globalhomeindex.org. The website allows for a selection of the language in which the participants wish to respond to the surveys; there were six languages available (English, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, German, and Hungarian); however, in the present study, the Spanish and Portuguese versions were used. The database was hosted in Argentina with all the legal protections required by the country for this type of study.

Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants did not receive any compensation for participating in the study. However, because a computerised version was used, the participants received personal feedback according to their answers reported on the scales.

Measures

Work orientation. The University of Pennsylvania Work-Life Questionnaire (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). was used to evaluate the type of relationship that employees reported having with their work, according to the distinctions between job, career, and calling proposed by Bellah and colleagues (1985). The evaluation consisted of presenting participants with three paragraphs, which required a respondent to choose whether they identified with either Mr./Ms. A (job orientation), Mr./Ms. B (career orientation), or Mr./ Ms. C (calling orientation), on the basis of a four-point scale. This scale was scored from 0 to 3, where 0 corresponded to “not like me at all,” and 3 corresponded to “very much like me.” The participants were categorised using the methodology proposed by Wrzesniewski and colleagues (1997): i.e., taking only the results of those participants who, having assigned a score to the three work orientations, gave only one of them the highest identification rank.

The original version of this instrument is in English, so it was translated into Spanish and Portuguese using the standards for educational and psychological testing of the American Educational Research Association (2018). A psychologist with experience in the development and validation of psychometric scales and knowledge of the English language translated the Scale into Spanish and Portuguese. The translation emphasised conceptual rather than literal translations with the intention of achieving a natural and appropriate language for a better comprehension of the participants. Moreover, another independent translator back-translated the University of Pennsylvania Work-Life Questionnaire to English. Finally, the versions were compared to achieve a satisfactory translation.

Flourishing. Participants completed the 12-item version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale by Mesurado and colleagues (2021). This scale measures the three aspects of human flourishing proposed by Keyes: i.e., social well-being (e.g., “I am committed to addressing the problems faced by society”); psychological well-being (e.g., “I find my life to be full of meaning”); and emotional well-being (e.g., “sad vs. h appy”). A fi ve-point L ikert s cale ( from 1 = “ strongly disagree” to 5 = “ strongly agree”) was used to measure the social and psychological dimensions, and a five-point semantic differential scale was used to measure the emotional dimension (from 1 = negative to 5 = positive).

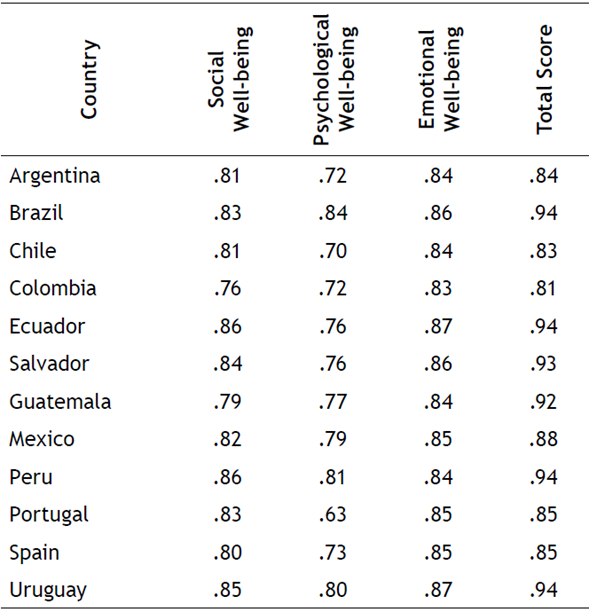

The original scale was developed in Spanish; consequently, items were translated into Portuguese and back into Spanish to ensure comparability, following the same procedure used in the translation of the University of Pennsylvania Work-Life Questionnaire. The McDonald’s omega of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale for each country is shown on Table 2.

Results

The first objective of our study was to explore work orientation in twelve Ibero-American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay). Table 3 shows the percentages of work orientations reported by participants from each country. The results indicate that 61% to 77% of the participants identified themselves as having a clear work orientation according to the definitions proposed by Bellah and colleagues (1985).

Moreover, between 10% and 15% of the participants from Ibero-America indicated that they had a job orientation at work (except Portugal, Spain, and Argentina), signaling that work is a way to earn enough money to support a person’s life apart from their job. In addition, between 14% and 26% identified themselves as having a career orientation: work marks a person’s advance in life by means of success in their profession. Finally, between 28% and 46% identified themselves as having a calling orientation, work is one of the most important parts of their life and motivates them to make the world a better place.

Initially, it was assessed whether there were sociodemographic differences (age, gender and educational levels) between adults who identified themselves as having a job, career or calling orientation in each country. No demographic differences were found.

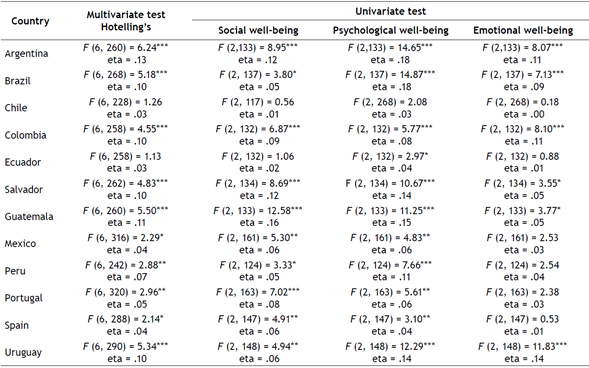

The second objective of this study was to investigate the effect of the work orientation on the different dimensions of human flourishing (emotional, psychological and social well-being) reported by participants from each country (see the descriptive analysis on Table 4). This objective was achieved using twelve Multivariate Analyses of Variance (MANOVA), one for each country, in which each of the three dimensions of flourishing was a dependent variable, and the three work orientations (job, career, and calling) were independent variables. The multivariate analyses evidenced that work orientation affects the levels of flourishing in all countries studied, except for Chile and Ecuador.

Table 4 Mean and standard deviation of flourishing level for the three work orientations for each country

Note: Standard deviations appear in parentheses.

In addition, the univariate analyses indicated that work orientation affects the different dimensions of human flourishing (emotional, psychological, and social well-being). The results are summarised on Table 5. Post-hoc Bonferroni tests were used to study the differences in each dimension of human flourishing among the different work orientations (see Table 6). In general, the results indicated that participants with a calling orientation reported higher levels of social and psychological well-being than participants with a job orientation. In addition, participants with a calling orientation reported higher levels of emotional well-being than participants with a job orientation only in six countries included in the study (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Salvador, Guatemala and Uruguay). Altogether, there are no differences in the levels of flourishing between participants with a calling orientation and participants with a career orientation; or between career and job orientation.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to explore work orientation in twelve Ibero-American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay). As we have previously indicated, our results show that 61% to 77% of the participants identified themselves as having a clear work orientation according to the definitions proposed by Bellah and colleagues (1985). These results are in accord with a recent study carried out in the United States, which indicated that 73% (n = 251) of the participants included in the study identified themselves as having a clear work orientation (Mantler et al., 2021).

In addition, the participants of Ibero-American countries identified themselves as only between 10% and 15% having a job orientation, except Portugal, Spain, and Argentina, which reached levels of around 20% and 29%. Mantler et al. (2021) found that 20% of the American participants were primarily job-oriented.

Moreover, the present study found that between 14% and 26% identified themselves as having a career orientation, and between 28% and 46% identified themselves as having a calling. It is important to note that most of the Ibero-American participants reported a higher level of calling in their work orientation than the American participants and similar levels of career orientation (Mantler et al., 2021). These differences from previous researchers highlight the importance of the cultural context in fully understanding adult work orientation. Ibero-American countries are characterised by high levels of traditional values, emphasising the social relevance of work, family, and social relationships over job income. These cultural values may explain the importance of identifying themselves as having a calling rather than a job orientation.

According to Crespo and Mesurado, “flourishing is more comprehensive than subjective well-being; in fact, for Aristotle, it is also more encompassing than the hedonistic or utilitarian concept of happiness. Hence, it does seem reasonable to view flourishing as a more complete category” (2015, p. 11). Because human flourishing is a relatively new concept, there are few empirical studies of the relationship between work orientation and flourishing life, especially in Ibero-American countries. Consequently, this study focused on the relationship between work orientation and human flourishing, with the aim of investigating whether the way people relate to their work in different countries has a significant impact on their flourishing. Specifically, the aim was to investigate whether the three different work orientations (job, career, and calling) affect flourishing in the twelve countries.

As we expected, the results indicate that the individuals who reported a calling orientation had higher levels of social well-being than the individuals who reported a job orientation; this was the case in all the countries with the exceptions of Chile and Ecuador. On the other hand, in general, there were no significant differences in social well-being between the individuals who reported calling and career orientations (the exception is Guatemala), and between the individuals who reported career and job orientations (the exception is El Salvador).

The repeated relationship found in the different countries between calling and social well-being is in accord with theoretical and empirical discussions regarding the calling orientation. Park and Rothwell (2009, p. 400) argue that an “individual sees his/her work as a calling when this work serves a community, when an individual is using his/her gift as a manifestation of the spirit for the common good, or when an individual feels deep gladness.” Furthermore, a study has found that employees who relate to work as a calling have higher levels of perceived social relevance in their work than those with a job or career orientation (Rodríguez et al., 2017).

Furthermore, our results indicate that individuals who reported a calling orientation had higher levels of psychological well-being than individuals who reported a job orientation; this was the case in all countries with the exception of three countries (Chile, Ecuador and Spain). In three Ibero-American countries (Brazil, Guatemala, and Uruguay), the results indicate that individuals who reported a calling orientation had higher levels of psychological well-being than individuals who reported a career orientation. In the other countries, there were no significant differences in psychological well-being between individuals who reported calling and career orientations. Also, in general, there were no significant differences in psychological well-being between individuals who reported career and job orientations, with the exceptions of Argentina and El Salvador.

From these results, it is possible to infer a clear relationship between a calling orientation and psychological well-being. That means that a calling has a positive effect on the psychological well-being of employees. Indeed, previous studies have found that life meaning (Duffy & Dik, 2013) and satisfaction with a specific domain (e.g., “I am very satisfied with being in business/being a manager”) were positively associated with a calling (Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, 2011; Duffy & Dik, 2013). Satisfaction with a specific domain and life meaning could be understood as aspects of psychological well-being because the scale used to measure flourishing includes items such as “I am happy with my current lifestyle,” “I find my life to be full of meaning,” and “I have a compass, a sense of mission that makes my life fulfilling and helps me to overcome the possible failures or contradictions that I experience”.

Finally, in six Ibero-American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Uruguay), the results indicate that individuals who reported a calling had higher levels of emotional well-being than individuals who reported a job orientation. In three Ibero-American countries (Brazil, Colombia, and Uruguay), the results indicate that individuals who reported a calling had higher levels of emotional well-being than individuals who reported a career orientation. In general, there were no significant differences in emotional well-being between individuals who reported career and job orientations.

It is important to highlight the finding that the relationship between work orientation and emotional well-being remains unclear in many Ibero-American individuals (only in six countries did we find that individuals who reported a calling had higher levels of emotional well-being than individuals who reported a job orientation). As demonstrated in previous studies, work orientation cannot be identified as a predictor of the degree of emotional well-being. One possible reason is that individuals who are calling-oriented could be more emotionally vulnerable regarding their vocation (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009). Also, previous studies have produced inconsistent results regarding the relationship between calling and life satisfaction. For example, Wrzesniewski and colleagues (1997) found that employees with a calling orientation reported higher levels of life satisfaction (conceptualised in this article as emotional well-being) than employees with a job orientation. However, Duffy and Sedlacek (2010) showed that perceiving a calling is weakly correlated with life satisfaction in students. On the other hand, a longitudinal study in the USA has demonstrated that financial success is associated with low levels of subjective well-being (emotional well-being) among individuals with relatively strong intrinsic work values, such as a calling orientation (Malka & Chatman, 2003). Consequently, further work is needed to clarify the relationship between emotional well-being and a calling.

Apart from one or two exceptions among the twelve countries, our study found no evidence of significant differences between a calling and a career orientation, or between a career and a job orientation, in the different dimensions of flourishing (social, psychological, and emotional well-being). A possible explanation may be that a career orientation is a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to work, and consequently, the level of individual differences in flourishing is not sufficiently clear to indicate a real distinction.

Implications

Knowing the work orientation of 3000 adults in 12 Ibero-American countries has a descriptive value in and of itself since it allows to characterise adults of working age. This article also offers essential information for employers to motivate their employees more effectively. The Ibero-American employees may need the employer to connect labour tasks with the employees’ meaning of life and highlight the aspect of the work that serves the community, not just use external motivation such as professional or economic development. In this way the employer is likely to increase employees’ retention and work engagement and develop a better connection with them.

Limitations and future research

The present study is exploratory and sets the groundwork for further research that addresses specific issues; for example, the differences among the socio-economic levels in each country. Other approaches might include testing the relationship between work orientation and flourishing by including more countries, and by taking into account the cultural and social environment of the countries. Moreover, an important limitation of this study is that it includes a majority of adults with a high level of education. Qualitative research could help explain the differences (or the absence thereof) in the relationships between work orientation and the different aspects of flourishing.1 2 3 4