Introduction

Mental disorders are estimated to affect more than 13% of children and adolescents worldwide (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2022). Surveys meta-analysis of representative samples from children and adolescents in high-income countries estimated that one out of eight children and adolescents show mental disorders that require treatment, with an overall prevalence of 12.7% (Barican et al., 2022).

In Latin America, reported prevalence figures of mental disorders range from 13% to 22% in population-based studies of children and teen mental health (Duarte et al., 2003; Paula et al., 2015; Vicente et al., 2012). In Uruguay, Viola et al. (2007) published a study involving 1,374 children aged 6 to 11 years, whose results showed that 22% of Uruguayan schoolchildren registered at least one significant symptom.

Regarding the age at which mental disorders begin, the results of a meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies showed that 34.6% of mental disorders appear before the age of 14 (Solmi et al., 2021). Most of these situations are not detected or treated promptly causing school problems, substance abuse, or comorbid disorders (World Health Organisation, 2021), negatively affecting family, social, academic, work, and economic environments (Asselmann et al., 2018).

It is relevant, therefore, to have valid and reliable screening devices and instruments for the early detection of mental health problems. There is a growing number of instruments with potential to be used for such purposes. Deighton et al. (2014) reviewed existing broadband instruments for the assessment of mental health and wellbeing reported by children, parents, and teachers, and found that 11 measures have adequate characteristics and psychometric properties for the assessment of this population. Within this set of instruments, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) is one of the most widely used, both for clinical and research purposes, for the detection of existing mental health difficulties in children and adolescents (Bryant et al., 2020). In addition, it has the advantage of being one of the few instruments to report a positive mental health score (Smedje et al., 1999).

The SDQ is made up of 25 items grouped into five subscales: one scale assesses strengths related to prosocial behaviour, and four scales assess mental health difficulties (conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, interpersonal problems with peers). The scales of conduct problems and hyperactivity are indicators of externalising type symptoms, and the scales of emotional symptoms and interpersonal problems with peers are indicators of internalising type symptoms (Goodman, 1997, 1999; Goodman, Lamping et al., 2010).

Despite its widespread use, the SDQ’s factor structure continues to be debated (Kulawiak et al., 2020; McAloney-Kocaman & McPherson, 2017).

To date, five reviewing studies have been published on the psychometric properties of the SDQ parent version for 4 - to 16-year-old children (Bergström & Baviskar, 2021; Hoosen et al., 2018; Saur & Loureiro, 2012; Stolk et al., 2017; Stone et al., 2010). Of these five papers, only two (Saur & Loureiro, 2012; Stone et al., 2010) report information on analyses of the internal structure of the instrument using general population samples.

The review by Stone et al. (2010) selected 48 studies, 14 of which reported data on factor analysis. In Saur and Loureiro’s (2012) review, 17 of a total of 51 selected articles assessed the dimensional structure of the questionnaire. Not all these papers reported the Goodness of Fit indices recommended in the guidelines for conducting factor analyses, such as those of Ferrando et al. (2022) and Lloret-Segura et al. (2014). At a minimum, absolute fit indices such as the Chi-square value, with its associated degrees of freedom and probability value, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and indices to describe the incremental fit such as the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), or the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) should be reported (Hooper et al., 2008, Hu & Bentler, 1999).

In order to complete and update the background report on the SDQ factor structure, we conducted a search for articles published from 2012 onwards. Table 1 shows the studies included in the reviews by Stone et al. (2010) and Saur and Loureiro (2012) as well as subsequent articles that meet the conditions of testing of the original five- and three-factor structures originally proposed by Goodman through a confirmatory factor analysis (with recommended fit indices), of the version completed by parents of children between 6 and 12 years of age from the general population.

The Goodness of Fit indices reported on Table 1 should be analysed according to the cut-off values suggested for each measure (Jackson et al., 2009). Considering that all study samples are greater than 250 in size, and that the questionnaire has 25 items, the recommended goodness-of-fit values are: CFI and TLI > .92, RMSEA < .07 (Hair et al., 2019) and x2/gl < 3 (Schreiber et al., 2006). These cut-off points are consistent if appropriate software is used for conducting factor analyses (MPlus, LISREL, FACTOR, SAS, among others) with categorical data, using the WLSMV, DWLS and Satorra-Bentler-corrected ML estimation methods, based on polychoric correlation matrices.

Table 1 Confirmatory factor analyses (5- and 3-factor) SDQ parent version

Note. In the case of more than one estimation method, the one with the best fit is reported: aSatorra-Bentler ML, bWLSMV, cDWLS. *boys, **girls.

As can be seen on Table 1, 11 of the 18 papers presented (Björnsdotter et al., 2013; Español-Martín et al., 2021; Gómez-Beneyto et al., 2013; Goodman, Lamping et al., 2010; Hoffmann et al., 2020; Kóbor et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2022; Sanne et al., 2009; Tobia & Marzocchi, 2018; Van Roy et al., 2008) report five-factor solutions with adequate psychometric indices according to current recommendations. Of the nine papers that analysed the structure of three factors, Björnsdotter et al. (2013) and Español-Martín et al. (2021) were the only ones that reported acceptable fit indices.

Considering the large number of articles that have analysed the SDQ’s psychometric properties in its 25 years of existence, the limited number of studies that confirm the original five- and three-factor structures is striking. Factor solutions that achieve good fit indices have been reported, but they deviate from the original theoretical model. For example, a study eliminated the prosociality scale, thus generating a two-factor solution referring to internalising and externalising difficulties or a single factor solution grouping the four difficulty subscales (Goodman, Patel et al., 2010). Others followed the path of testing second-order (Goodman, Lamping et al., 2010) or bifactor models (Kóbor et al., 2013), or of re-specifying the models allowing to correlate the measurement errors of the items (Percy et al., 2008). It has been hypothesised that the poor fit of the SDQ may be related to a “method effect”, that is configured when both positively and negatively worded items are used (Karlsson et al., 2022). Along these lines, van Roy et al. (2008) added a “positive interpretation method factor” to the five-factor model that is comprised of SDQ scale items that are reverse worded.

Considering the validity of the discussion about the SDQ factorial structure and that in Uruguay no validation studies were conducted with school-age children, we conducted an instrumental study in order to analyse the psychometric properties of the instrument in children from 7 to 12 years of age from the general population. In Uruguay there is a study on the psychometric properties of the questionnaire in children between 2 and 4 years of age that did not confirm any of the factorial models analysed (Castillo & Ortuño, 2018).

Thus, the specific aims of this paper are: (1) to evaluate the factorial structure of the SDQ for the original five- and three-factor models, (2) to analyse the reliability of the subscales, and (3) to provide descriptive data on the SDQ results according to sociodemographic variables.

Method

Participants

The sample was determined using non-probability cluster sampling taking into consideration both geographic distribution and the income quintile group of the families attending each school. The total sample was composed of the adult referents of 621 schoolchildren (52% girls) attending private schools in different cities of Uruguay, from 7 to 12 years of age (M = 9.75; SD = 1.37). The questionnaires were completed in 85% of the cases by their mothers. Of the total number of participants, 62% belonged to a medium socioeconomic level, 32% to a high level and 6% to a low level.

Instruments

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). In this paper we used the Río de la Plata translation published on the instrument’s official website (Goodman, n.d.). With a total of 25 items, the questionnaire provides a record of children’s behaviours, emotions and relationships depicting strengths and difficulties: prosocial behaviour (items 1, 4, 9, 17, and 20), conduct problems (items 5, 7, 12, 18, and 22), hyperactivity (items 2, 10, 15, 21, and 25), emotional symptoms (items 3, 8, 13, 16, and 24), and peer relationship problems (items 6, 11, 14, 19, and 23). Each item is scored on a 3-point Likert scale: 0 “not true”, 1 “true” or 2 “absolutely true”. Items 7, 11, 14, 21, and 25 must be inverted for the correct interpretation of the results. The four SDQ subscales of difficulties are grouped into externalising (“conduct problems + symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention”) and internalising (“emotional symptoms + peer relationship problems”) types of issues.

Sociodemographic information questionnaire. A questionnaire was developed to obtain sociodemographic data (age, sex) on the children and families. The survey included the questions of the Socioeconomic Level Index (INSE; Perera & Cazulo, 2016).

Procedure

We contacted privately managed educational institutions throughout the country and requested authorisation from the families of school-age children to conduct the study. Of the 1,940 families contacted, 840 agreed to take part in the study and signed the informed consent form after which they were given or sent the protocol including the sociodemographic questionnaire and the SDQ. A total of 621 families completed the questionnaires.

Ethical considerations

The procedure, consents and protocols have the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica del Uruguay, complying with the country’s research on human subject regulations, governed by Decree 001- 4573/2007 of the Executive Branch, and Law No. 18331 of Habeas Data, concerning personal data confidentiality.

Data analysis

Item analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA), reliability calculated with ordinal alpha, and descriptive analyses were performed for the Uruguayan sample.

CFA was conducted with the MPlus programme version 8.4. The categorical data matrix was used; missing data was handled using multiple imputation. The hypothesised model fit to the observed data was assessed using the Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance (WLSMV) method. EFA was undertaken with the FACTOR programme version 12.03.02, using polychoric correlations matrices (Freiberg et al., 2013), and applying the Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) method as the estimation approach. The number of factors were estimated using parallel analysis (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011), and the Robust Promin extraction method (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2019). The adequacy of the correlation matrix was tested using Barlett’s test of sphericity, and the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin measure. The fit indices used were x2/gl < 3, CFI and TLI > .92, RMSEA < .07 (Hair et al., 2019; Schreiber et al., 2006), and BIC (model with the lowest BIC value is preferred). The method of multiple imputation for missing data was implemented in the FACTOR programme (Lorenzo-Seva & Van Ginkel, 2016). The ordinal α-index was calculated to estimate reliability (Gadermann et al., 2012). The descriptive analyses were carried out using the JAMOVI programme.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

A CFA was carried out for the five-factor and three-factor models proposed by Goodman (Goodman, 1997, 1999; Goodman, Lamping et al., 2010). Table 2 presents the CFA results, showing that the data do not fit either of the two proposed models.

Item analysis and exploratory factor analysis

Given the results of the CFA, an exploratory strategy was used. We performed a descriptive study of the items (see Table 3) showing that items 11, 17 and 22 have severe asymmetry problems with absolute values > 3, that item 11 has severe kurtosis problems (> 10), and that items 17 and 22 (> 20) have extreme kurtosis issues (Kline, 2015). This analysis accounts for the need to use polychoric matrices and the robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation method (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Sampling adequacy was tested with Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the KMO adequacy measure. The Bartlett sphericity test was significant (6664.1; gl = 300; p < .000), with a KMO adequacy index = .54.

First, an EFA was performed limiting the extraction to five factors. The model fit indices were excellent (x2 = 350.75; df = 185; p < .000) x2/gl = 1.89, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .039 (90% CI (.005, .045); BIC = 1306). This output, however, was discarded when we noticed that the factor loadings of the items were grouped together without theoretical meaning. Therefore, another EFA was performed limiting the extraction to three factors. These results show a very good fit (x2 = 639.27; df = 228; p < .000) x2/gl = 2.80, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .055 (90% CI (.05, .08); BIC = 1763). Table 4 presents the factor loadings of the items for the three-factor model.

Descriptive data and reliability

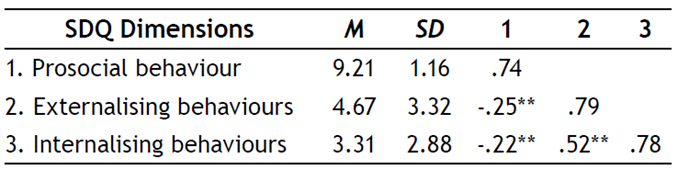

Table 5 registers descriptive data, correlations, and ordinal α-reliability for each of the three SDQ subscales, with indices between .74 and .78.

Table 5 Descriptive statistics and reliabilities three-factor SDQ

Note. Ordinal a-reliability indices are reported in bold on the diagonal. **p < .001.

Finally, Table 6 reports descriptive data for the three SDQ subscales according to sociodemographic variables.

Discussion

Since its inception 25 years ago, the SDQ (Goodman, 1997) has become one of the most widely used instruments for screening children and adolescents for prosocial symptoms and behaviours, for both clinical and research purposes. The SDQ is freely available in more than 80 languages and has been employed in a wide range of cultural contexts (Harry et al., 2019). However, controversy persists regarding its factor structure (Garrido et al., 2020; Kulawiak et al., 2020; McAloney-Kocaman & McPherson, 2017).

In the original psychometric studies, Goodman (1999) reported a five-factor structure through EFA using the principal component procedure. This procedure is currently totally discouraged (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). In the years following its creation, many of the psychometric studies of the SDQ internal structure using these procedures succeeded in replicating the five-factor structure (Goodman, 2001; Hawes & Dadds, 2004; Smedje et al., 1999). Recently, an increasing number of studies have conducted CFA, a much more psychometrically demanding procedure, with varying results. As presented in the background review, some authors were able to confirm the five-factor structure but many others had to test the three-factor structure or analyse and test’s internal structure alternatives other than those originally formulated by Goodman (1997; 1999).

According to Goodman, Lamping et al. (2010) the three-dimensional structure would be more appropriate for screening in the general population. The data from the present study, conducted with children from the Uruguayan general population, supports this model when performing an EFA, after the CFA for the five- and three-factor models did not achieve acceptable fit indices.

Numerous studies confirming the original five- and/or three-factor structures at exploratory levels did not achieve good fit when performing CFA (Caci et al., 2015). It is for this reason that some authors looked for analysis alternatives with fewer restrictions than those imposed by CFA, such as the Exploratory Structure Equation Modelling (ESEM;Schreiber et al., 2006). The results with this procedure also show weak factorial structures, with questionable indicators of cross-loads and multiple error correlations (Garrido et al., 2020).

The EFA conducted with Uruguayan schoolchildren data obtained very good adjustment indices for the three-factor structure, with adequate reliability indices. However, some items presented behaviour that merits review. Items 11, 17 and 22 presented severe asymmetry and kurtosis problems. On the other hand, when reviewing the factor loadings for the three-factor model, items 14, 21, and 22 saturated more than one factor, and in the case of item 22 factor loadings were distributed among all three factors, with values below .30. Some of these items should be inverted for the interpretation of their results, something that has been mentioned as a possible source of problems for psychometric analyses (Karlsson et al., 2022).

Considering that this is the first psychometric study of this instrument with school children in Uruguay, the descriptive data by gender, age, and socioeconomic level provides a reference for subsequent work and can be compared with the results obtained with the parent version in Spanish for Spain (Español-Martin et al., 2021) and Honduras (Harry et al., 2019). Using the cut-off points used by Español-Martin et al. (2021), the descriptive data shown on Table 6 allows us to affirm that most Uruguayan children (regardless of gender, age and socioeconomic level) fall into the “normal” range for prosocial behaviours (scores from 7 to 10), and externalising-type symptoms (scores from 0 to 7), and in the “borderline” range for internalising-type symptoms (scores from 0 to 3). This last data is especially striking since it is a general population sample, and a type of symptomatology that may draw less attention from adult referents.

This work has limitations that deserve attention. Although the sample was taken in different cities of the country and has diversity in terms of socioeconomic levels, it is not representative of Uruguayan school-age children. Furthermore, only the version completed by parents was considered in this study. Some studies suggest that the teachers’ reports are more reliable than the parents’ reports, or at least complementary in order to achieve a better assessment of children’s strengths and difficulties (Boman et al., 2016; Goodman et al., 2000). New studies should be conducted, with larger and more representative samples, including the teachers’ reports to complete the validation process of the instrument in the Uruguayan population by adding convergent, discriminant and criteria validity analyses, and including measurement invariance across gender and age.

Final considerations

It is undeniably essential to have screening instruments for symptoms and difficulties in children and adolescents that will allow early detection of behaviours that may require professional attention. The SDQ is one of the most widely used instruments for such purposes, but it still shows some inconsistencies in its internal structure. Twenty-five years after its creation and considering its multiple advantages, it is pertinent to review the evidence gathered over the years to adjust and strengthen this instrument. The present study contributed data from the Uruguayan population for the first time, which is an asset to the international debate on the instrument’s structure, as well as a supplement to researchers and clinical practitioners who wish to use it at the national level.